In 1800, the French were enchanted to make the acquaintance of the elegantly reclining, fashionably attired Madame Recamier, 1800 (fig. 1), as portrayed by Jacques-Louis David. A century later, in 1904, they were accosted by the splotchy, psychedelic figures in Matisse’s Luxe, calme, et volupté (Luxury, calm, and pleasure) (fig. 2). Such a radical change in style is startling, particularly given the glacial pace of artistic development over previous centuries. The Renaissance lasted about 200 years, the Baroque about a century. But in 19th-century France, style succeeded style within decades. Neoclassicism, introduced to France by David, was dominant for only forty years or so. Romanticism ruled for about twenty-five, Naturalism for about twenty. Impressionism (as an organized movement) and Pointillism survived barely a decade each.

What caused this rapid succession of styles in the 19th century, and what caused the styles to veer in the direction they did? Artistic trends are not the result of some ineffable, collective esthetic consciousness working its will; they are simply the styles that the majority of artists choose to embrace. Ultimately, the choices of individual artists shape a period’s styles. Most artists (like most butchers, bakers, and economics professors) accept without question the ideas popular among their contemporaries. We must seek the explanation for 19th-century changes in art in the cultural and philosophical context of that period.

Let us take a moment, then, to survey the 19th century, a period of astounding advances in human knowledge and enjoyment. To a thorough understanding of gross anatomy and physiology gleaned during the Enlightenment, scientists such as Virchow, Bell, Pasteur, and Lister added knowledge of cellular structure and activity, the brain and nervous system, the disease-causing role of bacteria, and the anesthetic effects of chloroform and ether. As a result of these and other advances in medicine and public health, the average life expectancy soared from about 30 years in 1800 to about 50 in 1900.

Not only were people healthier and longer-lived, they had more leisure time and more means to enjoy life. People of middle-class means and average education avidly read Hugo, Dumas, Dostoevsky, Dickens, and other novelists; they were thrilled by the operas of Verdi and Wagner; they listened spellbound to music by Beethoven, Chopin, and Tchaikovsky; they gazed at Old Masters in newly established art museums; they sauntered through grandly landscaped parks, and journeyed in comfort by rail or steamship.

New knowledge, new ideas, and new works of art circulated much more rapidly due to the explosion of communication and transportation technology during the Industrial Revolution. In 1800, news traveled only as fast as the sailboat or horse that relayed it, routinely taking weeks to cross an ocean or a continent. Books were set in type by hand and printed one laborious page at a time on handmade paper. By 1900, information could be transmitted almost instantaneously by telegraph or telephone, and inexpensive books and periodicals were printed from huge rolls of machine-made paper on electric-powered rotary presses with machine-cast type.

This increase in the speed at which information could be transmitted or reproduced was certainly a factor in the rapid changes in art: Reproductions and reviews of new artworks could travel more rapidly than ever before; thus, new styles could be more readily embraced or rejected. But this does not explain what caused artists to move from producing and appreciating the likes of the Madame Recamier to producing and appreciating the likes of the Luxe, calme, et volupté. The explanation for that lies not in the realm of technology, but in the realm of ideas.

Enlightenment Ideas and the Philosophy of Kant

The magnificent scientific and technological achievements of the 19th century were based on a few fundamental premises: that reality exists independent of man’s mind; that man can know reality by means of reason, observation, and logic; and that he can act on his knowledge to improve his world and enjoy his life. Unfortunately, while these ideas were widely held to be true, neither the men of the Enlightenment nor their successors could philosophically defend them. In particular, they could not defend the idea that what man knows by means of reason is, in fact, reality. This left them vulnerable to a philosophy that brought dire practical consequences: the philosophy of Immanuel Kant (1724–1804).

In the late 18th century, Kant devised a philosophy based on the premise that man’s mind is invalid, that his senses distort the data they encounter and thus deliver not knowledge of reality, but knowledge of a pseudo-reality—a “world of appearances” that Kant called the “phenomenal world.” Reality as it really is, the world of “things in themselves” (Kant’s “noumenal world”) is out of man’s rational reach and can be known (if at all) only by non-rational means—that is, by intuition, faith, or feelings.

Over the course of the 19th century, Kant’s ideas were increasingly embraced by philosophers, accepted by intellectuals, and absorbed into mainstream culture throughout Europe and the United States. They afflicted everything from science to politics to education to art—including our particular concern: painting. As we will see, respect for reason among painters and art critics declines and then disappears in the course of the century. It is no coincidence that both Karl Marx and Henri Matisse came to prominence during the 19th century; the works of both were born of Kantian premises.

We will resume our discussion of the causal connection between Kant’s philosophy and modern art following our survey of 19th-century French painting, which will provide much evidence in support of the connection.

Writings of 19th-Century French Painters

Most of the influential developments in art over the course of the 19th century either originated or were thoroughly explored in France. To discover the ideas behind these developments, we will examine the paintings and writings of eighteen artists who meet two criteria. First, each exercised a major influence on contemporary or subsequent artists. Second, some of the artists’ comments on the nature of art were recorded and passed down to us. We will also consider the writings of three prominent art critics (Charles Baudelaire, John Ruskin, Emile Zola) who were closely associated with specific artists and movements.

None of these artists or critics presented an organized theory of esthetics. Our focus will therefore be on four important issues that recur in their writings.

1. Is formal training for an artist necessary or even useful? Will learning techniques, such as linear perspective and anatomy, benefit an artist, or obliterate his originality?

2. What role do reason and emotions play in the creation of art? Does art depend on rational thought, or on feeling? Must an artist choose one or the other?

3. What is the relationship between style and subject? Which is more important: the “how” or the “what” of the artwork, the method or the content?

4. Who is competent to judge art: viewers, other artists, professional art critics, or a combination of the above?

Although all these issues are directly related to art and its interpretation, they also presuppose philosophical ideas about how man gains knowledge of reality. An artist’s or critic’s position on this fundamental issue will govern his entire approach to the creation or evaluation of art.

The elephant in the room—always present but seldom discussed—is the question, “What is art?” Anyone commenting on the four issues above has at least an implicit idea of what art is, yet only a few of our artists discuss it. In the rare cases when such definitions are offered, we will, of course, consider them.

When reading artists’ writings, we must remember (indeed, it would be difficult to forget) that few artists could spare the time to become philosophers, scholars, or intellectuals. Many of their comments are casual references from correspondence, in which they understandably did not bother to define their terms or state their ideas with rigorous precision. Since knowing an artist’s background often clarifies such statements, we will look at each artist’s life and work before reading what he has to say about art. The context often elucidates a pithy but perplexing phrase, so most of the quotes included are of substantial length.

Attempting to translate 19th-century artists’ comments into modern esthetic terminology would risk misrepresenting their views. Moreover, for our purposes, such translation is unnecessary since the information we seek is straightforward. Does an artist approve of education? Does he consider reason (thought, conscious mental effort) more important in creating a work of art than feelings (emotions, subconscious urges, whims)? Does he believe an artist ought to focus more on what he is painting, or how he is painting it? Whom does he consider qualified to judge art, and why? The answers to such questions are usually obvious, if an artist’s thoughts on them are recorded at all. Thus, despite confusing terminology and imprecise formulations, we will see clear trends in each of our four issues over the course of the century.

Prelude: The Academy and the Salon

In 1648, after decades of divisive religious wars, Louis XIV of France (ruled 1643–1715) resolved to promote a sense of national identity and unity by establishing the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture. To become a member of the Academy was an honor for any artist and a boost for his career. Members tended to be conservative rather than avant-garde, since being chosen required the approval of Academy members who had already been elected—sometimes decades ago.

By the late 17th century, Academy members controlled commissions in public art and teaching in fine-arts academies throughout France, including the most prestigious one, located in Paris. The Paris school still exists as the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, the name it was given after the French Revolution.

Members of the Academy and their pupils were “encouraged” by their sponsor, the government, to produce didactic paintings and sculptures that would teach the French people to be patriotic and pious. The subjects of choice were moralizing narratives from Greek, Roman, and French history. For a century and a half, the most lucrative commissions in France went to painters who produced such government-approved “history paintings.” Portraits, landscapes, and still-lifes were considered mundane, unprestigious ways to supplement income between history paintings.

Academy members chose the works that were displayed at the annual Paris exhibition known as the Salon. Well into the 19th century, having paintings displayed at the two-month Salon was the most effective—and virtually the only—way for an artist to sell his work. The royal family, government officials, nobles, and wealthy bourgeoisie flocked to the Salon to view, discuss, and occasionally purchase the latest in French art. By the 1840s, attendance had reached a million or so, and writing critiques of the works on display was a thriving business. Until the 1880s, having work consistently accepted for the Salon was the hallmark of an artist’s success, but the conservative Academy could, and did, block admission to the Salon of the work of artists whose subjects or styles they disapproved. This was the state of the French art world when the first Neoclassical artist appeared on the scene.

Neoclassicism

Jacques-Louis David (1748–1825)

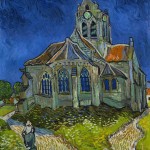

Typical of mid-18th-century art is Boucher’s Music Lesson, 1749 (fig. 3), with its charming, elegant, aristocratic young people acting out stories of love and gallantry amid lush landscapes, the whole painted in pastel colors and shades of deep green. In the world of Boucher and fellow Rococo artists such as Fragonard and Watteau, what mattered were love, gaiety, elegance, wit, and grace. Jacques-Louis David trained with Fragonard, and his early works such as Sappho and Phaon, 1770s (fig. 4), are thoroughly Rococo in subject and style.

But while the Rococo was flourishing in France, another movement was rising in Italy—a reversion to the ancient Greeks and Romans, a new classicism. By this time, imitating the ancients was much easier than it had been for Renaissance artists. The quest for knowledge of Enlightenment scholars led to widely published archeological excavations in Italy. Yet a thousand or so years of exhumed classical antiquity supplied artists with choices as bewilderingly varied as the elephant presented to the blind men. An artist might adopt the subjects of Greek myth or Roman history. He might adopt the calm and dignity of Early Classical Greek sculpture, the idealized bodies of High Classical sculpture, the emotions and dramatic movement of Hellenistic Greek sculpture, or the naturalistic portraits of late Hellenistic or Roman sculpture. He might latch onto tunics and togas, symmetry and balance, or stark whiteness.

In 1755, Johann Joachim Winckelmann, the most renowned archeologist of the 18th century, advocated a return to the “noble simplicity and quiet grandeur” of the ancients.1 At nearly the same time, Diderot (1713–84)—the guiding force behind the Encyclopedia, that epitome of the Enlightenment’s systematization of knowledge—declared that any honest man who took up pen, brush, or chisel has a didactic purpose: ”to render virtue lovable and vice odious.”2

In 1784, David rejected his Rococo roots with the Oath of the Horatii (fig. 5), the image of stoic, patriotic Romans setting out to war that marks the beginning of Neoclassicism in France. David’s new style harked back to the severe and dignified mood of the Roman Republic, with noble and heroic figures determined to die if necessary while defending their principles. To emphasize the Republican setting, David incorporated archeologically accurate details of costume, furniture, and architecture. His own contribution (seldom evident in other Neoclassicists) was a sense for drama and emotional impact. In this work, he has accomplished that with the contrast between the upright, stoic men and the huddle of wailing women.

The Oath of the Horatii illustrates that David had dramatically changed not only his subjects but his style. He cut off the depth with a wall or backdrop. He eliminated extraneous and distracting elements. David’s compositions were balanced, the focus obvious, the figures and background cropped at carefully calculated points. Rather than Rococo pastels and deep greens, David now favored somber colors: cream, dull orange, and slate blue against brown. All the lines and contours were sharp and clear. Individual brushstrokes were so meticulously applied as to be imperceptible.

Although he consciously imitated the ancients, David was no second-rate copyist. His distinctive style was evident even when his subject was not classical. In the Death of Marat, 1793 (fig. 6), painted to honor one of the French Revolution’s most ruthless leaders, he used the same techniques: somber colors, shallow depth, crisp lines and details.

Note that David’s meticulous rendering did not mean he reproduced every detail he saw. Marat habitually worked in his bath because he suffered from a repulsive and painful skin disease. David, who had visited Marat at home the day before Marat was stabbed, certainly knew of the skin condition. In this portrait, David chose to eliminate it, transforming Marat into a handsome, heroic martyr. Although David included many precise details, he was, in fact, highly selective.

David on Training

David had little to say about the education of artists, but his own rigorous academic training shows in his meticulous depiction of people and objects, and in his command of perspective and other technical skills. In time, he established a successful atelier where he trained many young artists. Presumably, then, he considered such training beneficial.

David on Reason, Emotions, and Art

One of David’s most famous pronouncements relates to the function of art. In 1793, the year of the Reign of Terror, he told his colleagues at the Revolutionary Convention:

Your Committee [i.e., the Committee that David himself led] has, therefore, considered the arts in the light of all those factors by which they should help to spread the progress of the human spirit, and to propagate and transmit to posterity the striking examples of the efforts of a tremendous people who, guided by reason and philosophy, are bringing back to earth the reign of liberty, equality, and law. The arts must therefore contribute forcefully to the education of the public.3

David’s idea of which virtues the arts should teach are (literally) revolutionary, but his idea that art’s primary function is didactic goes back to ancient times. Plato proposed legal restrictions on artists, so that their works would show only proper virtues to citizens of his Republic. Roman Emperors erected monuments to remind their subjects of the glories of the Empire. In the Middle Ages, the clergy permitted art because images could educate illiterate laymen about Christian stories and doctrine. Louis XIV in the 17th century encouraged art that he thought would teach his subjects to be pious and patriotic. To view art as didactic is incorrect, but not at all novel. (We will consider the proper function of art later.)

For our present purpose, the relevant point about using art as a didactic tool is the assumption that underlies such use. If art is meant to teach, then it has to be created by a process of thought and for a specific purpose. If a viewer gains knowledge from it (rather than simply experiencing an emotion), then the viewer must use his mind as well. It follows that, for David, reason has a very large part both in creating and interpreting art.

Elsewhere, David states the artist’s need for reason more explicitly:

The artist, therefore, must have studied all the qualities of humankind; he must have a great knowledge of nature; he must, in a word, be a philosophe. Socrates, able sculptor; Jean-Jacques [Rousseau], good musician; the immortal Poussin, tracing on a canvas the most sublime lessons of philosophy, are witnesses enough to prove that genius must have no other guide than the torch of reason.4

Philosophe in the 18th century had a very specific meaning: It referred to French Enlightenment intellectuals who believed that the natural world could be known by the use of reason. David was asserting that an artist needed to be (in modern terms) both an abstract thinker and a scientist.

David on Style and Subject

David noted in 1796:

The Greeks had no scruples about copying a composition, a gesture, a type that had already been accepted and used. They put all their attention and all their art on perfecting an idea that had been already conceived. They thought, and they were right, that in the arts the way in which an idea is rendered, and the manner in which it is expressed, is much more important than the idea itself.5

Does this mean that David considered style more important than subject? Based on his idea that art’s function is primarily didactic, he clearly did not mean a painter should ignore content and think only about line, color, and so forth. Most likely he means that originality in subject is not necessary—that it is acceptable to paint (as David often did) a subject from Greek, Roman, or French history, as long as one presents one’s own interpretation or theme.

David’s ambiguity on this matter illustrates a major weakness in 19th-century writing on art. No 19th-century artist or critic began his writings on esthetics by defining such basics as subject, style, or theme, much less the broader abstraction “art,” hence none could discuss these matters with rigorous clarity. Early in the 19th century, the lack of definitions was not a major issue. Artists had similar training and shared many premises, even if they could not articulate them. A century later, however, avant-garde artists no longer shared those premises. At that point, as we will see, the fact that traditional artists could not state exactly what they stood for crippled their ability to defend themselves.

David on Judging Art

David asserted that rather than being sold immediately to the wealthy, art should be submitted to the judgment of the public. Artists would receive an income from the exhibition’s admissions fees, and the public’s taste would be improved.6 He also argued that artists were not necessarily the best judges of art:

Your Committee has decided that, during a period when art, like virtue, must be reborn, to leave the judgment of the productions of genius to artists alone would be to leave them in the rut of habit, in which they crawled before the despotism they flattered. It belongs to those stout souls to whom the study of nature has lent a feeling for truth and grandeur to give a new impulse to the arts and bring them back to the principles of true beauty. Thus he who is gifted with a fine sensibility, though without culture, and the philosopher, the poet, and scholar, each in those different things which make up the art of judging the artist, pupil of nature, are the judges most capable of representing the tastes and insights of entire people in the task of awarding Republican artists with the palms of glory.7

Final Words on David

Although David was a prominent political figure during the French Revolution, he quickly accepted Napoleon’s rule. In the thirty-two-foot wide Coronation of Napoleon, 1805–07, David faithfully recorded the extravagant costumes and rituals favored by Napoleon. After Napoleon was sent to exile on St. Helena in 1815, David retreated into self-imposed exile in Brussels, where he died a decade later.

David was a first-rate and original artist in both subject and style. Unfortunately, most of his students and followers produced lifeless, insipid copies of classical art and of David’s paintings. Only one of them became a major force in French Neoclassical painting.

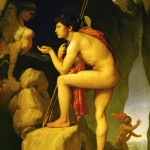

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780–1867)

Ingres was the unlikely figure who shouldered the banner of Neoclassicism after David’s exile. Following a few years’ study with David in the 1790s, he struck out on his own, producing distinctive but decidedly non-classical works. Although Grande Odalisque, 1814 (fig. 8), has David’s extreme clarity and precision, its subject is radically different: an undulating female with a contorted pose and bizarre proportions (e.g., three extra vertebrae elongate her spine). Front lighting emphasizes her sinuous outline. The colors are neither Rococo pastels nor sober browns, but pastels with an acidic tint. None of these characteristics was adopted from David or from Greek and Roman art—they were unique to Ingres.

Ingres became popular and influential in France only after he drastically revised this youthful style. The change is marked by the Vow of Louis XIII, 1824 (fig. 9), which illustrates a 1626 episode in which King Louis XIII dedicated France to the Virgin Mary. The Vow displays Ingres’s characteristically meticulous attention to detail and texture, but the Virgin Mary bears no visible kinship to the Grand Odalisque. Instead, her conventional proportions and colors recall High Renaissance works such as Raphael’s Madonna di Foligno, ca. 1512 (fig. 7).

After the 1824 Salon exhibition, Ingres (just returned from an eighteen-year sojourn in Italy) was welcomed as the leader of the French Neoclassicists. Although he continued to do conventional history paintings, he was also the most sought-after society painter of the day. Works such as Madame Rivière, 1805 (fig. 10), and Monsieur Bertin, 1832 (fig. 11), portray sitters who were elegant, wealthy, confident, and content. Echoes of Ingres’s early work still appear, especially in the sinuous curves and outlines, the sophisticated color combinations of women’s clothing, and the meticulous finish. The brushstrokes are so fine that the work almost seems painted in enamel rather than in oil paint. Ingres’s career lasted well into the 1860s.

Ingres on Training

Like David, Ingres wrote little on art. Also like David, he was a respected teacher who always had numerous students, so we can assume he believed in the value of a rigorous education in drawing, color, perspective, and so forth. He also firmly believed in studying the works of great artists:

What do those so-called artists mean when they preach the discovery of the “new”? Is there anything new? Everything has been done, everything has been discovered. Our task is not to invent but to continue, and we have enough to do if, following the examples of the masters, we utilize those innumerable types which nature constantly offers to us, if we interpret them with wholehearted sincerity and ennoble them through that pure and firm style without which no work has beauty. What an absurdity it is to believe that the natural disposition and faculties can be compromised by study—by the imitation, even—of the classic works!8

Ingres did not mean that artists should slavishly imitate the ancients, any more than they should slavishly copy models in the studio. Copying was a way to train the eye: “One must always copy nature, and learn to see well. That’s why one studies the ancients and the Old Masters, not to imitate them, but, I repeat, to learn to see.”9

Ingres on Reason, Emotions, and Art

Ingres emphasized the role of thought in the creation of art. In 1813 he noted:

When one knows one’s craft well, when one has learned well how to imitate nature, the chief consideration for a good painter is to think out the whole of his picture, to have it in his head as a whole, so to speak, so that he may then execute it with warmth and as if the entire thing were done at the same time.10

Painting, then, involves thought: A good painter plans the work out in his head before he touches a brush to canvas.

Ingres also stated:

Anti-classic art, if one may even call it an art, is nothing but an art of the lazy. It is the doctrine of those who want to produce without having worked, who want to know without having learned; it is an art as lacking in faith as in discipline, wandering blindly because of its having no light in the darkness, and demanding that mere chance lead it through places where one can advance only by means of courage, experience and reflection.11

Ingres on Judging Art

Ingres wrote:

The more sublime efforts of art have no effect at all upon uncultivated minds. Fine and delicate taste is the fruit of education and experience. All that we receive at birth is the faculty for creating such taste in ourselves and for cultivating it. . . . It is up to this point, and no further, that one may say that taste is natural to us.12

For Ingres, the ability to judge art is something one must work to acquire by continually studying art. It requires mental effort and education.

In sum, Ingres believed that learning, creating, and judging art all require significant mental effort.

Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot (1796–1875)

The third and final Neoclassical painter we will consider is Corot, who is roughly contemporary with Ingres. Corot’s training included study under a pupil of David. Like Ingres, he soon found that history painting was not his preferred subject. In 1826, at age thirty, he confessed, “I have only one aim in life, which I want to pursue steadfastly; to make landscapes.”13

Probably because history painting was still considered the best painting, Corot’s landscapes always have a few figures or some sign of human presence and activity. The Bridge at Narni, 1826 (fig. 12), painted a few years after Ingres’s Vow of Louis XIII (fig. 9), is a well-ordered landscape dominated by a bridge and roads. In Diana Bathing, 1855 (fig. 13), the landscape fills the painting, but the small figures near the center refer to Greek myth.

Corot’s early style resembles those of David and Ingres, in that he renders details and lines with great precision and without visible brushstrokes. In contrast to them, he prefers bright, cheerful hues (green, yellow, blue), and he shows strong contrasts of sunlight and shadow. More than earlier French artists, Corot loved to sketch in the open air. Back in the studio, he worked these “notes” into compositions with figures.

Thirty-seven years after Bridge at Narni, Corot painted Memory (Souvenir) of Mortefontaine, 1864 (fig. 14). Figures still dot the landscape, although now they are contemporary and anonymous rather than participants in a narrative, and the landscape no longer represents a distinctly identifiable place. Corot’s style has also changed radically. Many of his late landscapes lie in perpetual silvery brown twilight, details blurring into darkness. Look, for instance, at the soft smears that represent leaves. This late style was particularly easy to imitate, which (added to the fact that Corot often signed the work of his students) soon made him a favorite target of forgers. One early biographer said wryly that Corot painted 3,000 paintings, of which 10,000 were in the United States.14

In Corot’s early paintings, the world is a bright and cheerful place. In his later works, it is much gloomier. But it remains a place where man belongs: Corot never paints landscapes bereft of human beings or their effects.

Corot on Reason, Emotions, and Art

Around 1828, about the same time that he painted the Bridge at Narni (fig. 12), Corot wrote:

Drapery and, in general, all things that are fairly regular need much exactness. I see, too, how meticulously one must follow nature, and not be satisfied with a hasty sketch. How often, looking at my drawings, have I been sorry that I hadn’t had the energy to spend half an hour more on them. . . . Nothing should be left to indecision.15

Such conscientious observation and recording implies that painting requires rational effort. But twenty years later, Corot had changed his mind:

Be guided by feeling alone. We are only simple mortals, subject to error; so listen to the advice of others, but follow only what you understand and can unite in your own feeling. Be firm, be meek, but follow your own convictions. It is better to be nothing than an echo of other painters.16

Does he simply mean, “To thine own self be true”? Apparently not, for the passage continues:

While I strive for a conscientious imitation, I yet never for an instant lose the emotion that has taken hold of me. Reality is one part of art; feeling completes it. Before any site and any object, abandon yourself to your first impression. If you have really been touched, you will convey to others the sincerity of your emotion.17

Years later Corot told a friend that he had never been taught, but had faced nature and found his own style: “Yes, I put white in all my colors, but I swear I do not do it on principle. It is my instinct, and I obey my instinct.”18

Ingres said one must think out the whole composition of a painting inside one’s head. Corot said thought (“conscientious imitation”) and feeling are equally important and equally necessary, and introduced the term “instinct” for the way he applied color. This is the first time in this article that we have seen emotion mentioned as a requirement for a painter, but as we will soon see, Romantic painters had been advocating it for quite some time before these passages from Corot were recorded.

Final Words on Corot

Corot was roughly contemporary with Ingres, but he began with a sharp, clear style and ended with one that was blurry and fuzzy. Such changes are common. An artist rarely signs on to a particular movement and resolutely cleaves to it for decades: witness David and Ingres, among many others. The artist’s ideas and values may change, or he may simply decide to embrace a style that seems more saleable. Corot began as a Neoclassicist but ended his career with a style that influenced the Impressionists, whose first exhibition was in 1874—only ten years after Memory (Souvenir) of Mortefontaine (fig. 14).

Summary of Neoclassicism

Despite wide-ranging differences in subject—from Napoleon to harem girls to Italian landscapes—the Neoclassical painters we have looked at share several important characteristics. Their choice of subjects usually reflects what artists had for centuries believed to be the function of art: to educate men by showing the good and the beautiful. The figures are grand and heroic. The landscapes offer reminders of human achievements. Their world is an exciting, dramatic place, where heroic and dramatic events are possible. The Neoclassicists also have a distinctive style for showing this world: precise lines, meticulous details, and balanced compositions.

The French Neoclassical movement peaked from the 1780s to the 1820s. After that, it was replaced on the cutting edge of art by Romanticism. Neoclassical style and subjects did not, however, disappear. David (d. 1825), Ingres (d. 1867), and Corot (d. 1875) all had numerous students and followers. Ingres was particularly influential: For decades, he ran a successful atelier where he taught aspiring painters his views and methods. Unfortunately, most of his students lacked the passion and innovation of their teacher. Imitating the ancients and other Neoclassical artists often resulted in static, boring paintings. The Romantic movement was, in part, a reaction against such bland works.

Before we turn to the Romantics, let us briefly review the Neoclassicists’ responses to the four issues that we are following regarding art and philosophy.

Is training necessary in order to be a good artist? David said an artist should be a philosophe, a combination of abstract thinker and scientist. Ingres advised careful study of classic works. David, Ingres, and Corot were all academically trained, and all ran highly successful ateliers for aspiring artists. Their attitude toward learning clearly reflects the Enlightenment assumption that man can know reality through the senses and logical thought, and can act to improve himself and his world.

What role does reason play in the creation of art? David said, “The guide of genius is the torch of reason.” Ingres said good art is the product of hard work and education. The young Corot said art requires close study, but by the 1850s, he considered feelings and instinct as important as rational thought. On a broader scale, David and Ingres assumed reason was involved in art because they saw art’s purpose as didactic, and both teaching and learning involve disciplined mental effort. This reflects Enlightenment ideas on the importance of rational thought.

What is the relationship between style and subject? David said that style is more important than subject, but he seems to have meant that it is acceptable to use well-known subjects, so long as one interprets them for oneself. Ingres apparently concurred when he said that artists did not need to seek out the new: “Our task is not to invent but to continue.”

Who should judge art? David thought the people should judge art, since artists themselves were not always competent to do so. Ingres said that taste is based on education and experience, which implies that esthetic judgment requires observation and rational thought. Ingres’s attitude, in particular, reflects the Enlightenment assumption that reality is knowable through sense perception combined with mental effort.

Romanticism

We now backtrack from Ingres, Corot, and their mid-19th-century followers to the 1810s, when Romantic painters began to appear in France. Scholars agree that Romanticism’s origins reach back at least to Edmund Burke’s 1756 Inquiry into the Origins of the Sublime. But what exactly was “Romanticism”? No artist at the time nor any scholar since has been able to define it. By the mid-1820s, about 150 different definitions had been suggested, none of which gained general acceptance. Romanticism’s premises and implications differed too substantially from one country to another, one decade to another, and particularly from one discipline to another.19

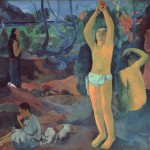

In philosophy, German Romantics such as Fichte (1762–1814), Schelling (1775–1886), and Schopenhauer (1788–1860) advocated outright mysticism. “The whole body is nothing but objectified will, i.e., will become idea.”20

In literature, authors such as Friedrich Schiller (1759–1805), Victor Hugo (1802–1885), Fyodor Dostoevsky (1821–1881), and Edmond Rostand (1868–1918) stressed the individual and his emotions.21 Over a century later Ayn Rand pointed out that a man’s emotions depend on his values, and his values depend on what he chooses (consciously or unconsciously) as his standard.22 Hence, in the most fundamental sense, Romanticism is the school of literature that shows man with free will, and its most distinctive characteristic is a sequence of events caused by the choices of the characters—a plot.23 But this connection between emotions, values, and volition was unknown to 19th-century artists and intellectuals.

In the visual arts, Romanticism was largely confined to painting. Beginning with Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720–1778), Henry Fuseli (1741–1825), and Francisco de Goya (1746–1828), artists rebelled against the “noble simplicity and quiet grandeur” that Winckelmann had advocated, and which, in the form of Neoclassicism, had swept through Europe during the late 18th century. Romantic painters focused on subjects calculated to arouse strong passions. The passions could be as positive as love or as negative as terror: The important thing was to make the viewer feel something.

Baron Antoine-Jean Gros (1771–1835)

Gros did so many paintings for Napoleon that he was known as Napoleon’s propagandist, although his imposing canvases also made him popular with the Bourbon kings after Napoleon’s defeat. Napoleon in the Pesthouse at Jaffa, 1804, a huge 18 x 23 feet (fig. 15), is an early example of French Romanticism, illustrating not only the Romantics’ striving to evoke emotions but several other features that became characteristic of the movement. First, Gros depicts a contemporary event rather than one from Greek or Roman history. Here, Napoleon visits soldiers stricken with the bubonic plague during his 1799 campaign in Palestine. Second, although Gros portrays Napoleon as a hero, he makes the men surrounding Napoleon of lesser stature. Most are anonymous; a few are dying in agony. In David’s early Neoclassical paintings, by contrast, men tended to be equal in heroism and dignity. Third, Gros portrays exotic people and places. Napoleon’s 1798–99 expedition to Egypt and the Near East ignited a passion for the outlandish and extraordinary in Gros and other French painters. The depiction of contemporary events, ordinary men, and exotic settings all became typical of French Romanticism.

Despite these very non-Neoclassical characteristics, Gros still shows signs of David’s influence. Especially noticeable are the use of sharp details and sober colors, such as dark red and deep brown. The two painters differ radically, however, in the way they compose pictures. David’s figures are often arranged parallel to the picture plane, with a strong focal point that draws the viewer’s attention. Gros favors diagonals that pull the viewer’s eye toward the background, and his compositions verge on the chaotic: Our eyes jump from one spot to another.

Gros is the exception to our rule of studying only those influential artists who left comments on art. A student of David who became a Romantic, he is included, despite the lack of surviving writings, because he vividly reminds us that the creation and adoption of artistic styles are not mindless, evolutionary, or collectivist. Gros could have persisted with classical subjects and the calm nobility of his teacher, David. But an artist’s style always depends on the choices of that artist, and Gros’s choices soon led him to create paintings quite different from David’s in style and subject.

Théodore Géricault (1791–1824)

Gros showed a heroic Napoleon surrounded by ordinary men. Géricault, his contemporary, preferred anonymous modern figures in dramatic situations, as in An Officer of the Imperial Horse Guards, 1814 (fig. 16). Also characteristic of Géricault’s style is violent movement: His men and animals leap and writhe. He has a predilection for gloomy colors and for fire, smoke, and dark shadows. His brushstrokes are noticeably larger and looser than those of David, Ingres, or Corot: Look, for example, at those on the horse’s head in Officer, which suggest the animal’s energy and motion.

Visible brushstrokes are not always to be disparaged. A painter might, for instance, decide to do larger, less meticulous brushstrokes on hair or clothing, in order to focus the viewer’s attention on a face: We tend to look most closely where there is most detail. An artist might use such brushstrokes to suggest rapid movement or a dreamy atmosphere. Whether meticulous or loose brushstrokes are appropriate depends on the context of the painting. We will see a definite trend in the type of brushstrokes favored by painters across the span of the 19th century.

Géricault’s breakthrough painting was the twenty-three-foot wide Raft of the Medusa, 1819 (fig. 17), in which he depicted a recent event that had outraged his compatriots. Like Gros’s painting of Napoleon visiting plague victims, this work was calculated to raise a strong emotion in the viewer. This time the emotion was a combination of horror and pity.

In 1816, the French frigate Medusa was wrecked off the west coast of Africa. The captain, officers, and about 250 others piled into six lifeboats, promising to tow ashore a makeshift raft with another 150 passengers. But the slow-moving raft was soon cut loose, and its desperate passengers resorted to cannibalism—possibly murder. When rescuers finally arrived, they found only ten survivors. Since the Medusa’s inexperienced captain had obtained his post through nepotism, the wreck was quickly transformed into a political scandal.24

After nearly three centuries of paintings that glorified France’s history and rulers, Géricault’s Raft of the Medusa was a stunning reversal: It was the first painting to imply that the French government could be stupid or careless, and it marks the beginning of a shift from art that praised rulers and government to art that showed them with warts and all, or even warts only. Yet the Raft†was awarded a gold medal in the Salon of 1819, was purchased by the Louvre for the French national collection in 1824, and by 1830 was considered a masterpiece.

How does Géricault keep our eyes moving around the gruesome drama shown on this huge canvas? Instead of lining up his figures parallel with the front edge of the painting (as David did in Oath of the Horatii, fig. 5), Géricault arranges the figures to recede diagonally into the picture space, drawing our eye with them. Using somber colors and eerie light, he evokes a dismal mood. Notice especially the range of strong emotions Géricault depicts, from grief to despair to agony, and even (in the flag-waving figure at the top of the pyramid) hysterical hope. The dark colors, restless movement, and highly charged emotions are all characteristic of Géricault in particular as well as Romantic painting in general.

Géricault on Training

One of Géricault’s most oft-quoted statements, probably written in the early 1820s, is this:

Supposing that all the young people admitted to our schools were endowed with all the qualities needed to make a painter, is not it dangerous to have them study together for years, copying the same models and treading approximately the same path? After that, how can one hope to have them still keep any originality? Haven’t they in spite of themselves exchanged any particular qualities they may have had, and sunk the individual manner of conceiving nature’s beauties that each one of them possessed in a single, uniform style? The nuances that can survive this sort of confusion are imperceptible; and each year we see with disgust ten or twelve compositions, carried out in about the same way, painted from one end to the other with a disheartening perfection, and showing no trace of originality.25

At first glance, Géricault appears to disparage all education, but in fact, he was only attacking education in France’s state-run academies, where instruction tended to become fossilized. Such criticism had been put forward since the late 18th century.26 In some respects, the criticism was valid, and we will hear other artists repeat it. However, elsewhere Géricault clearly appreciated the need for education:

I have always believed that a good education must be the necessary basis for the exercise of any profession, and that it alone can give us true distinction in whatever career we may choose . . . [But] it should not be the purpose of this institution [the Academy] to create a race of painters, rather, it ought simply to provide true genius with the means for self-development.27

Géricault also advocated the study of earlier artists:

One must not be ashamed of returning to tradition; the beautiful in the arts can be achieved only by comparisons. Each school has its own character. If one could succeed in uniting all of their qualities would one not have reached perfection? But that requires incessant effort and great love.28

Clearly Géricault did not reject tradition, even though he was revolutionary in his subject matter.

Géricault on Reason, Emotions, and Art

The previous quote implies that Géricault considered both thought (mental effort) and emotion necessary to produce art. When he discussed how obstacles affect genius, however, he emphasized the emotional rather than the rational: “Everything which opposes the irresistible advance of genius irritates it, and gives it that fevered exaltation which conquers and dominates all, and which produces masterworks.”29

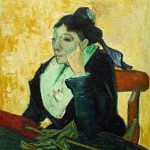

Eugene Delacroix (1798–1863)

When Géricault died in 1824, at the age of 33, Delacroix became the most prominent of the French Romantics. Ingres’s Apotheosis of Homer, 1827 (fig. 19), and Delacroix’s Death of Sardanapalus, 1827 (fig. 18), which appeared at the same Salon exhibition, vividly illustrate the differences between the Neoclassicists and the Romantics. Seldom were two such radically different paintings produced in the same city, within a year of each other.

The Apotheosis of Homer shows the author of the Iliad and the Odyssey as a genius to whom all ancient and modern artists pay homage. Homer and his admirers are arranged in front of a classical Greek temple, under a clear blue sky. The Death of Sardanapalus, on the other hand, shows a despot from ancient Assyria (centered in modern Iraq) who, learning he was about to be conquered, ordered his henchmen to slaughter his harem girls and his horses so no one else could enjoy them. Sardanapalus, reclining at the upper left, impassively observes a maelstrom of death and destruction.

The styles as well as the subjects of these two paintings are diametrically opposed. Ingres’s composition is balanced and symmetrical, with a strong focal point established by the temple’s pediment and by the central placement of Homer and the angel who crowns him. Delacroix’s composition has a long diagonal that moves the viewer’s eye back to Sardanapalus’s reclining figure. The rest of the scene is asymmetrical, full of chaotic movement. In the Ingres, the light pours in from the left, casting few shadows. In Delacroix, the room is dimly lit and full of shadows, making the scene even more turbulent and confusing.

The very brushstrokes are radically different. Ingres’s outlines are precise, his brushstrokes indistinguishable. Delacroix’s brushstrokes are easily visible (as were his predecessor Géricault’s), and his outlines are fuzzy or blurred. The type of brushstroke Delacroix used was clearly what he considered appropriate for this subject. In a portrait of his aunt, he depicted the facial features with precision but the lace of her headdress with a very free hand.30

For Ingres and the other Neoclassicists, the purpose of art was didactic: to depict truth and beauty, and thus teach the viewer how to be a better, more moral person. The restrained, low-key mood is appropriate for such an intellectual aim. For Delacroix and the Romantics, the purpose of art was to evoke a strong emotion—with Sardanapalus, a dozen variations on terror—and gloomy and chaotic styles were appropriate for that goal.

Evoking emotion is what Delacroix did best. In one of his most famous paintings, Liberty Leading the People, 1830 (fig. 20), Delacroix shows common people in a dramatic situation, as Géricault had done. Here, in a commemoration of one of Paris’s many rebellions against royal authority, allegorical Liberty triumphantly leads Parisians across piles of corpses and rubble. At the left, Delacroix included a self-portrait in a top hat. The boy on the right soon became the inspiration for Gavroche in Hugo’s Les Misérables. As in Death of Sardanapalus, Delacroix here favors blurred details and murky colors without much contrast of light and dark.

Soon after 1830, Delacroix switched from painting contemporary events, such as rebellion in the streets of Paris, to depicting exotic milieus (Women of Algiers, 1834) and religious subjects (Jacob Wrestling with the Angel, 1854–61). In these, Delacroix used a brighter palette, but even here his colors are murky compared to the clear hues of Ingres. Murky colors and blurry details remain characteristic of Delacroix’s style throughout his career.

Delacroix on Reason, Emotions, and Art

In 1853, Delacroix wrote:

Nature is far from being always interesting from the standpoint of effect and of ensemble. If each detail offers a perfection which I shall call inimitable, these details collectively, on the other hand, rarely present an effect equivalent to the one which results, in the work of the great artist, from the feeling for the ensemble and the composition.31

Selecting details and arranging a composition implies that conscious thought has a role in the creation of art. Delacroix’s assertion that artwork conveys a message confirms this: “Is there not a moral attached even to a fable? Who should reveal this better than the artist, who plans every part of the composition beforehand in order that the reader or beholder may unconsciously be led to understand and enjoy it.”32

But Delacroix also saw emotions as invaluable, and disparaged rational thought when painting:

I do not at all like reasonable painting. I recognize that it is necessary for my turbulent mind to be agitated, to destroy its bonds, to try out a hundred manners before arriving at the goal, the need for which torments me in everything. There is an old leavening, a pitch-black depth to satisfy. If I am not agitated like a serpent in the hands of a pythoness, I am cold. This must be recognized and be submitted to; and this is a great pleasure. Everything that I have done well has been done in this way.33

It is no wonder that Ingres, a highly cerebral painter, regarded France’s most famous Romantic as the devil incarnate. Passing Delacroix at an exhibition he growled, “I smell sulfur.”

Charles Pierre Baudelaire (1821–1867)

We now turn briefly to a man who is not an artist but an art critic—a relatively new phenomenon. During the 19th century, several factors combined to make art critics enormously influential. Due to the Industrial Revolution, the standard of living was rising, and more people could afford to purchase art. Increased wealth and productivity also led to widespread literacy and greater leisure, after centuries when most people had struggled from dawn to dusk for mere subsistence. Inventions such as the steam-powered printing press, wood engraving, photography, lithography, and inexpensive wood-pulp paper made it easier and faster to transmit ideas and images. More people than ever saw and read about the latest developments in art.

Yet there were still no accepted standards for judging art. This provided the perfect breeding ground for the emergence of professional art critics, who made it their mission to tell the public which type of art they ought to approve of. Critics’ reviews of the Paris Salon exhibitions were printed in periodicals and circulated widely in pamphlet form. Among the critics who achieved lasting fame were Baudelaire, Ruskin (see section on the Naturalists), and Zola (see section following Manet).

Baudelaire was born in 1821, about the time Romanticism burst onto the French art scene, and died in 1867, the year Ingres died. His Flowers of Evil, 1857, was arguably the century’s most influential collection of poetry. The opening lines to his readers reveal Baudelaire’s horrendous sense of life:

Stupidity, delusion, selfishness and lusttorment our bodies and possess our minds,and we sustain our affable remorsethe way a beggar nourishes his lice.

Baudelaire’s published comments praising Delacroix boosted that artist’s fame and influence. In fact, much of what is accepted as the Romantic attitude toward art was actually Baudelaire’s interpretation of Delacroix.

Regarding Delacroix’s style, Baudelaire said:

From Delacroix’s point of view, line does not exist; for no matter how thin it may be, a maddening geometer can always suppose it thick enough to contain a thousand others; and for colorists, who seek to imitate the eternal palpitations of nature, lines are never other than the intimate blending of two colors, as in the rainbow.34

Peer intently at Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People (fig. 20) and its outlines actually seem to vibrate.

What makes Delacroix distinctive, according to Baudelaire, is not a style or subject but an emotion—a feeling, rather than a way of thinking or acting:

There remains for me to note one last quality in Delacroix to complete this analysis, the most remarkable quality of all and one that makes him the true painter of the 19th century: it is the singular and obstinate melancholy that runs through all his works, and that is expressed in his choice of subject, by the expression of his faces, through gesture, and in his kind of color.35

In his obituary of Delacroix, Baudelaire pithily summed this up: “Delacroix was passionately in love with passion, and coldly determined to seek the means of expressing it in the most visible way.”36

Remember that no one had properly defined Romanticism. This is Baudelaire’s attempt in 1846, when the movement in France was already several decades old:

Romanticism is precisely located neither in the choice of subject nor in exact truth, but in the mode of feeling. They looked for it outside themselves, and it is only to be found within. For me, romanticism is the most recent, the most up-to-date, expression of the beautiful. . . . Who says romanticism, says modern art—that is, intimacy, spirituality, color, aspiration toward the infinite, expressed by every means at the disposal of the arts.37

No one could pick a work of Romantic art out of a gallery exhibition based on this vague “definition.”

But after all, why does it matter whether we can define romantic art, or indeed art in general? Is it not enough to be able to affirm, on gut instinct, that an object is or is not a work of art? No. Without a proper definition, we do not have a firm basis for understanding, discussing, or judging art. Art could be “anything an artist produces,” or “any object of pleasing color and/or shape,” or “anything an art critic decrees to be art.” When we consider other definitions of art offered by 19th-century artists, it will begin to be obvious why works such as Matisse’s Luxe, calme, et volupté were not only accepted by 1900, but acclaimed. (We will consider the proper definition of art in the Conclusion.)

From the quote above, it is clear that in the debate over the role of reason vs. emotion in art, Baudelaire is pro-emotion. Closely related to this emphasis on emotion is the idea—shared by Baudelaire and a number of prominent contemporary critics—of “art for art’s sake,” as opposed to art that serves didactic purposes. 38 A didactic purpose requires that the artist carefully work out the details that will convey his message, and that the viewer sees the details and grasps the message. But if art exists only for its own sake, that rational element is unnecessary. The artist is free to focus only on trying to express his own emotions. Furthermore, if art exists only for its own sake, has no purpose beyond existing, there can be no standard for judging what good art is, or what is and is not art.

Summary of Romanticism

Although we have not yet heard a proper definition of Romantic painting, we have observed several of its recurring characteristics. The subjects are ordinary men in dramatic situations, exotic places, or both. The narratives are usually contemporary—few are taken from Greek or Roman history, or even French history. Man is the center of the world in these paintings, and his situation is often dramatic, sometimes heroic. But in contrast to the paintings of the Neoclassicists, he is usually suffering, struggling, sometimes dying. Although he may have grandeur and dignity, the mood is never one of unadulterated triumph or joy. Liberty Leading the People (fig. 20) does so over piles of corpses. The aim of Romantic painters was to rouse passions, but not necessarily positive ones.

The lighting tends to be gloomy or murky, the colors subdued. Compared to the Neoclassicists, Romantics’ brushstrokes are easily visible and there is less attention to texture. The Romantics also create compositions with dramatic movement via diagonal lines, avoiding symmetry and balance.

With these characteristics of subject and style in mind, you might think it would be easy to distinguish a Neoclassical painting from a Romantic one. Yet, as we saw when discussing Corot, artists do not sign on to one movement or set of rules and stay with it throughout their lives. Arch-Romantic Delacroix painted Medea Kills Her Children, 1838 (fig. 22), a subject from Greek myth—albeit a violent one. Napoleon at St. Bernard, 1801 (fig. 21) is akin to Géricault’s Officer of the Imperial Horse Guards, (fig. 16), but it was painted in 1801 by David, the first French Neoclassicist, when Géricault was only ten years old. An artist can and often does change style and subject to achieve different purposes, or as he develops his own ideas. A study of historical styles is a study of the dominant trends of a period; one should never slip into the error of assuming that any particular artist was constrained to follow the trend. Each made his own choices about style and subject.

What about the issues we have been following regarding art and philosophy? The Romantics we have considered discussed only two of them. With regard to training, Géricault said an education (including study of earlier artists) is necessary, but believed academic studies had the potential to stunt originality. With regard to the role of reason and emotion in the creation of art, Géricault and Delacroix agreed: Both considered thought necessary, but emotion even more important. Baudelaire went a step beyond that. He advocated “art for art’s sake,” rejecting the old (and incorrect) idea that art ought to be primarily didactic. Creating and grasping didactic art required rational thought; “art for art’s sake” opened the way for art that expressed whatever whim the artist might feel.

This shift, from reason to emotion as the essential faculty in the production and evaluation of art, springs from the Kantian notion that sensory observation and logic do not provide a means for knowing reality. If they do not, what is left? Some sort of feeling, whether it be called divine inspiration, intuition, or gut instinct. Over the decades that follow Baudelaire and the Romanticists, we will see the derogation of reason and the emphasis on emotion becoming more and more pronounced.

Naturalism

The Neoclassicists and Romantics vied with each other for several decades, but by the 1850s, both Ingres and Delacroix were mainstream artists. Each had a roomful of paintings on display at the 1855 Universal Exposition in Paris.

The rebels by that time were the Naturalists. Like Romanticism, Naturalism began abroad and was adopted by French painters. This time the models were British landscapes such as John Constable’s Hay Wain, 1821 (fig. 23), exhibited in Paris in 1824 to lavish praise from Delacroix and others. Constable was famous for appearing precisely to record such natural elements as foliage, light, and moisture. (Compare the trees in the Hay Wain with those in the background of Boucher’s Music Lesson, fig. 3.) The emphasis in Constable’s paintings was on nature; if men appeared at all, they were anonymous farmers and workers.

Before we look at how the French “translated” Constable, a brief note on the use of the term “Naturalism” by art historians and by Ayn Rand. Historically, Naturalist painters (sometimes called “Realists”) date to the mid-19th century. Prominent among them were Constable in England and Millet, Courbet, and the Barbizon School in France. They did not have a manifesto or a single strong leader, but they are recognizable from their preferred subjects: landscapes or hard-working farm laborers.

As opposed to the art-historical use of Naturalism, Ayn Rand uses the term primarily to describe a literary phenomenon. Among Romantic novelists, the hero is “an abstraction of man’s best and highest potentiality, applicable to and achievable by all men, in various degrees, according to their individual choices.”39 Naturalists, on the other hand,

claim that a writer must reproduce what they call “real life,” allegedly “as it is,” exercising no selectivity and no value-judgments. By “reproduce,” they mean “photograph”; by “real life,” they mean whatever given concretes they happen to observe; by “as it is,” they mean “as it is lived by the people around them.”40

The essential difference between the Naturalists and Romantics, she says, is that Romantics believe man has free will, while Naturalists do not.

Do the senses in which art historians and Ayn Rand use the term “Naturalism” overlap? In assessing a painting, it is difficult to tell whether an artist intended his subjects to be perceived as having the power of choice, but a quotation from Millet, a French Naturalist painter, does indicate a desire to show people as if they had no free will: “I want the people I represent to look as if they belonged to their station, and as if their imaginations could not conceive of their ever being anything else.”41

Let us return to the matter of the historical Naturalists. In 1863, Millet pedantically explained:

In The Sheep That Have Just Been Shorn, I have sought to express that kind of bewilderment and confusion that the sheep experience when they have just been stripped of their wool, and also the curiosity and astonishment of those which have not yet been shorn on seeing such denuded creatures rejoin the flock.42

The Neoclassicists showed dignified, courageous men in dramatic situations. The Romantics showed ordinary men in dramatic situations. The Naturalists showed ordinary men performing exhausting, mundane physical labor, and the profound emotions of . . . sheep.

Naturalist painters often include a great deal of detail in their works. In fundamental terms, however, the amount of detail is irrelevant. The difference between them and the Neoclassicists or Romantics relates to subject rather than style. Monsieur Bertin, (fig. 11), by Neoclassicist Ingres, is represented with extreme detail, from the wrinkles on his face to the reflection on the arm of the chair. What situates M. Bertin†far outside the realm of Naturalism is the fact that it shows not a nameless laborer but a man who is impatient, intelligent, aggressive: a vivid and unique character.

Jean-Francois Millet (1814–1875)

“Since I have seen nothing in my life but fields,” Millet wrote, “I try to say as best I can what I have seen and felt as I worked there.”43 In actuality, although Millet was the son of peasants, he studied painting in Paris with David’s pupil Gros, one of the earliest French Romantics. He was hardly a country bumpkin, and his subjects were consciously chosen, not determined by his upbringing.

Millet’s earliest works were conventional, charming portraits of middle-class Frenchmen. By the late 1840s, however, he had settled on a favorite subject: toiling peasants. In The Gleaners, 1857 (fig. 24), the women turn their faces away, backs bowed with fatigue—anonymous and exhausted. Although the sturdy figures stand out sharply against the fields, the details within each figure are blurred and indistinct.

Millet liked to position his figures in a somber setting, under cloudy skies or at dusk. Often he set the horizon line high in the picture, reducing the amount of sky and hence the amount of light that reached the figures.

Millet’s choice of subjects was novel, especially compared to the heroic drama of the Neoclassicists and the emotional revels of the Romantics. Half a century earlier, Jean-Baptiste Greuze (1725–1805) had depicted the lower classes, but always with a moralizing, didactic message. Millet’s works are not moralizing but nostalgic. He shows men doing obsolete jobs with old-fashioned tools, but his workers are on an epic scale—one or two usually fill a large canvas. It is as if Millet is recalling a long-past golden age when living by manual labor and the literal sweat of one’s brow was an idyllic occupation.

Millet on Reason, Emotions, and Art

Millet wrote in 1863:

It is not so much the subjects represented that create beauty, as the need one feels to represent them. And this need of itself creates the degree of power sufficient to accomplish the work. One might say that everything is beautiful, provided that it occurs at the right time and place, and that nothing can be beautiful that appears out of season.44

What assumptions underlie this statement? First, an artist’s feelings matter more than his subject or execution. Second, strong feeling will give an artist the power to produce a work of art: If you want it badly enough, you will have the ability. Third, beauty is subjective: Anything can be beautiful in the right place, at the right time. We have already seen an intimation of this turn from reason toward emotion in Delacroix, who said he had to be turbulent and agitated to do his best work.

Millet on Judging Art

Millet’s statement that everything is beautiful “at the right time and place” is our first sign of a trend toward a new way of judging art. The new standard is: There are no standards; everything is contextual and subjective. What you consider beautiful I might find appalling, and there is no way to choose objectively between our evaluations.

Gustave Courbet (1819–1877)

Millet changed the subject matter of French art. Courbet went further, attacking what had been the esthetic norms. Like Millet, he painted hard-working laborers—but laborers of a quite distinct sort. Writing about The Stone-Breakers, 1851 (destroyed), Courbet described one man as wearing pants so filthy they could stand up by themselves, and the other as having scurvy and wearing shoes with holes in them.45 By comparison, Millet’s peasants seem heroically clean and healthy. Courbet also offended traditionalists with his paintings of nudes, which depicted, in garish colors, fat women and toil-worn men.

Courbet is most famous for paintings such as Burial at Ornans, 1849-50 (fig. 25). The canvas is so huge (9 x 21 feet) that the figures are all life-size, although many of them are clumped together in a solid mass. Courbet depicted the villagers who came to one particular funeral, including (as he states in a letter) the 400-pound mayor of Ornans, the choir boys, the gravedigger, and the pall-bearers.46

The Artist in His Studio, 1854–55 (fig. 26), is another huge image of ordinary life, this time nineteen feet wide. Except for the partially draped model in the center, it is full of mundane figures who fail to capture our attention either by their size, color, or interaction with each other. Like a Naturalistic novel whose characters meander plotlessly through event after event, The Artist in His Studio lacks a focal point. No aspect is stressed. No message is conveyed. It is, said Courbet, “society at its highest, its lowest, and its average; in a word, it is how I see society with its concerns and its passions.”47

We have seen that Romantic Delacroix used looser brushstrokes than Neoclassical Ingres. Courbet was even more radical: He applied paint to canvas with a palette knife and spatula, which had earlier been used only to mix paints. Although he had practiced copying Old Masters, after 1848 Courbet consciously rejected painting with precise detail. His heavy-handed application of paint on most of the works done after that date was a gesture of defiance against the high finish of Academic paintings and the politics associated with it.

Courbet on Training

Courbet had an immense influence through his paintings and through his writings on art, but he had no pupils. Why? In 1861, he wrote, “I deny that art can be taught, or, in other words, maintain that art is completely individual, and that the talent of each artist is but the result of his own inspiration and his own study of past tradition. . . . ”48 In the 1820s, Géricault said academic training destroys originality. Courbet was much more extreme: He said no one can teach anything to an aspiring artist. The only way to learn is to observe the works of earlier painters. As a member of the ruling body of the Paris Commune in 1871, Courbet went so far as to abolish the state-run Ecole des Beaux-Arts. (It was reinstated after the six-month reign of the Commune ended.)

Courbet on Reason, Emotions, and Art

In the previous quote, Courbet said that the second requirement for being a good painter is inspiration. Inspiration has been attributed to many sources, but rarely to rational thought.

Aside from the comment on inspiration, Courbet also asserted:

The basis of realism is the denial of the ideal . . . Burial at Ornans was really the burial of Romanticism. . . . We must be rational, even in art, and never allow logic to be overcome by feeling. . . . By reaching the conclusion that the ideal and all that it entails should be denied, I can completely bring about the emancipation of the individual, and finally achieve democracy. Realism is essentially democratic art.49

Here Courbet seems to advocate reason over feeling and the real over the ideal. But what did he mean by being “rational” in art? As always, we must be wary of assuming a 19th-century artist used terms as we do. For Courbet “rational” is a political rather than an epistemological matter. As a socialist, he believed his art could help achieve the type of political system he desired in France. Courbet’s art was didactic, but instead of promoting ethics or morals, its purpose was to win converts to a socio-political system. The “ideal,” his nemesis, was the didactic, moralizing art promoted in the government-supported French academies. “Art must be dragged in the gutter!”50 cried Courbet. Not coincidentally, Courbet vehemently rejected “the futile goal of art for art’s sake.”51

Courbet on Style and Subject

Courbet also had radical and uncompromising ideas on what should be represented:

The art of painting must consist only in the representation of objects that are visible and tangible to the artist. No period can be reproduced except by its own artists, by the artists who have lived in it. I maintain that an artist of one century is entirely incapable of reproducing things of a previous or future century, that is, of painting the past or the future.52

Anti-monarchical and anti-academic Courbet rejected mythological, historical, or fantastic subjects: no School of Athens, no sculptures of the Biblical David, no Raft of the Medusa (fig. 17). If you did not see it with your own eyes, then, according to Courbet, you should not attempt to portray it.

Courbet on Judging Art

Like Millet, Courbet was a subjectivist when judging art, holding that no universal or objective standards of beauty are possible. “Beauty, like truth, is relative to the time in which one lives and to the individual capable of comprehending it.”53

John Ruskin (1819–1900)

John Ruskin ranks as one of the most influential art critics of the 19th century or any other. His writings had such tremendous impact in France that he rates inclusion here, even though he is British.

Ruskin’s 1844 description of the campagna (the plains surrounding Rome) serves to illustrate why he is so influential and what sort of influence he had:

The earth yields and crumbles beneath his foot, tread he never so lightly, for its substance is white, hollow, and carious, like the dusty wreck of the bones of men. The long knotted grass waves and tosses feebly in the evening wind, and the shadows of its motion shake feverishly along the banks of ruin that lift themselves to the sunlight. Hillocks of mouldering earth heave around him, as if the dead beneath were struggling in their sleep; scattered blocks of black stone, four-square remnants of mighty edifices, not one left upon another, lie upon them to keep them down. A dull purple poisonous haze stretches level along the desert, veiling its spectral wrecks of massy ruins, on whose rents the red light rests, like a dying fire on defiled altars. . . . From the plain to the mountains, the shattered aqueducts, pier beyond pier, melt into the darkness, like shadowy and countless troops of funeral mourners, passing from a nation’s grave.54

This is brilliant writing, with vivid details, unexpected yet evocative similes, and a powerful theme to hold the description together. But that theme is human death and the disintegration of all human works, no matter how great. Ruskin here displays an appallingly malevolent sense of life. Like Plato, he wrote beautifully and persuasively from a viewpoint that is disastrously flawed.

Ruskin’s sense of life originated with a strong religious bent, which also affected what he considered the purpose of art. He condemned earlier landscape artists because their work “has never made us feel the wonder, nor the power, nor the glory of the universe. . . . That which ought to have been a witness to the omnipotence of God, has become an exhibition of the dexterity of man.”55 For Ruskin, art is didactic, and what it ought to teach is piety.

Ruskin on Training

Ruskin asked:

How are we to get our men of genius: that is to say, by what means may we produce among us, at any given time, the greatest quantity of effective art-intellect? . . . [Y]ou have always to find your artist, not to make him; you can’t manufacture him, any more than you can manufacture gold. You can find him, and refine him: you dig him out as he lies nugget-fashion in the mountain-stream; you bring him home; and you make him into current coin, or household plate, but not one grain of him can you originally produce.

An artist is born, not made, but once he is born, he must be shaped and prepared, in Ruskin’s words, for “full service” to society’s needs.56

Ruskin on Style and Subject

Ruskin wrote in 1844 that his purpose was “to insist on the necessity, as well as the dignity, of an earnest, faithful, loving study of nature as she is, rejecting with abhorrence all that man has done to alter and modify her.”57 Man-made is bad; natural is good. (Not surprisingly, the environmentalists consider Ruskin one of their founding fathers.)

Also in 1844, Ruskin asserted that “Every class of rock, earth and cloud must be known by the painter, with geologic and meteorologic accuracy.”58 Any change the artist makes in an object’s appearance is due to “powerless indolence or blind audacity.”59

Delacroix said the artist must pick out elements from nature and rearrange them. Ruskin decreed that a painter must choose one section of nature and record it exactly as it is. This furnished the theoretical basis for Naturalistic painting: Paint what you see, record everything with microscopic detail, and do not dare change a single thing.

Ruskin on Judging Art

Ruskin’s requirements for judging art follow logically from his insistence on the artist’s duty to faithfully reproduce nature. In 1858, he stated flatly:

Sound criticism of art is impossible to young men, for it consists principally, and in a far more exclusive sense than has yet been felt, in the recognition of the facts represented by the art. A great artist represents many and abstruse facts; it is necessary, in order to judge of his works, that all those facts should be experimentally (not by hearsay) known to the observer; whose recognition of them constitutes his approving judgment. A young man cannot know them.60

Ingres had said that one needs education and experience to judge art. Ruskin, however, proceeds on a different tack: The knowledge one requires is experience of “many and abstruse facts.” Presumably, if the viewer recognizes that an artist has presented accurate representations, he will approve the artist’s work. By Ruskin’s standards, few people, young or old, would be qualified to offer an opinion on art.

Summary of Artists on Art to the 1860s

The Naturalists, at mid-century, are a good place to pause and consider the issues regarding art and philosophy that we have been following since David’s time.

Is training necessary for an artist? The Neoclassicists David, Ingres, and Corot advocated rigorous training and ran successful ateliers for aspiring artists. Géricault, a Romantic, asserted that academic training might stunt originality, but still considered education necessary. Courbet, a Naturalist, said art cannot be taught: One must simply study nature and earlier artists. Ruskin said artists were born, not made, but advocated that those born with artistic talent be “refined” to serve worthy purposes.