Selectivity (or Why Size and Everything Else in Art Matters)

Suppose you were an experienced artist commissioned to paint a portrait of me. To get an idea of what would be involved in the project, consider just one of the countless choices that you would have to make: How will you paint my complexion?

My skin is pale with a few freckles. If you decide to include the freckles, I will appear to be an outdoorsy type and perhaps a little naive, since freckles are often associated with youth and innocence. If you choose to show me by candlelight, the rosy glow will add color to my skin, so I will appear healthy. If you decide to show me under fluorescent lights, I will appear pale and ill. If you give me a heavily veined red nose, I will appear to have a drinking problem. And so on.

The point is that even such a seemingly minor detail as the way in which you represent my skin will convey significant information to viewers about your estimate of me, my lifestyle, my health, my character.

How will you decide the matter? As an artist, you will decide it by asking yourself which of my characteristics (real or imagined) you think are most important and by employing an approach that will emphasize those characteristics. And this is not only how you will decide this issue; it is how you will decide every detail of the portrait, from the style of my hair (a chignon? a Mohawk?) to the way I tilt my head or hold my jaw. More broadly, this is how an artist decides every detail included in any type of painting, from a narrative of historical or mythological events, to a landscape, to a still life.

Selectivity based on an artist’s judgment of what is important is what makes every work of art a unique expression of an artist’s mind. Since he begins with a blank slate (be it a canvas, a piece of stone, or a lump of clay), an artist must constantly make choices about every element he will include and how much emphasis he will give it. He may make such choices consciously or subconsciously, but make them he must. This fact goes to the genus of art, which is, as Ayn Rand put it, “a selective re-creation of reality.”1

On what basis does an artist decide what is important? He decides by reference to his most fundamental assumptions about man and the world, for which Miss Rand coined the phrase “metaphysical value-judgments.” “Metaphysical” means pertaining to the nature of reality. “Value-judgments,” in this context, refers not to ethical value-judgments, but to judgments about the nature of the world (or reality) and man’s relationship to it. Is reality a stable environment in which things happen according to natural law—or is it a place in which the inexplicable occurs? Does man have free will and thus the ability to steer the course of his life—or is he predetermined to act as he does and thus incapable of directing his actions? Is the world conducive to man’s success and happiness—or is man doomed to failure and misery?

For millennia, philosophers have written hefty tomes discussing such questions and attempting to provide answers. Artists address the same issues, but they show rather than tell. Into a single visual image, whether a painting or a sculpture, they incorporate a multitude of metaphysical value-judgments. In a previous article in The Objective Standard, I concluded that the theme of Anna Hyatt Huntington’s Cid (fig. 1) is, “A strong, courageous warrior rouses his troops to follow him into battle.”2 Huntington’s choice of this theme implies not only that the virtues of courage and leadership are important, but also that there are values for which one ought to be willing to face danger, that man has the ability to recognize such values, that he has free will and can choose to fight for them, and that the world is the sort of place where values can be achieved. These are the metaphysical value-judgments expressed by the sculpture.

An artist’s metaphysical value-judgments are what direct his selectivity, and this fact goes to the differentia of art. Adding the differentia to the genus, art is “a selective re-creation of reality according to an artist’s metaphysical value-judgments.”3 Every detail of an artwork is chosen, and the artist chooses the details based on what he consciously or subconsciously believes to be true about man and/or the world in which he lives. Through his work, an artist says, “This is true, this is real, this is important—pay attention to this.” And this is why art can have such a powerful effect on us. To observe an artist’s concretization of his fundamental convictions is to observe the world as he observes it. If we share those convictions, seeing them made visible can give us immediate pleasure and fuel to pursue our goals.

Learning To Look at Art

In viewing a work of art, we react emotionally to the metaphysical value-judgments implied in the work, and we do so whether or not we know explicitly what those value-judgments are. If we do know explicitly what they are, however, we can deepen our understanding and increase our enjoyment of the work. The way to zero in on the metaphysical value-judgments implied in an artwork is to identify the work’s theme. Whereas in “Getting More Enjoyment from Art You Love” I demonstrated how to discover the theme of a sculpture, in the pages that follow I will show how to apply the same approach to discover the theme of a painting. To understand the process of identifying the theme of an artwork is to understand how to observe, think about, and evaluate art independently, without the constant intervention of a critic or historian. My goal in this article is to teach you this process. Before we begin, however, a few words about my approach.

If I were teaching a novice how to bake, I would not hand him a volume of complex bread recipes; if I did, he might well give up in frustration before understanding the first thing about baking. Rather, I would provide him with a recipe for basic bread and tell him what to do and why at each stage of the bread-making process. Consequently, the novice would quickly grasp the essence of the process and be able to produce basic bread on his own. After gaining some experience in the basics, he could confidently move on to improvisations such as varying the ingredients and oven temperature, and he could begin to read and understand more complex recipes. The same holds true for the study of art.

If one is relatively new to the subject, immersing oneself in volumes of complex, highly abstract art criticism will raise more questions than it will answer. Consider, for instance, this passage by Sir Kenneth Clark on the great Renaissance painter Titian:

Great artist as Titian was, there is nearly always something external in his portraits. In a way he is too commanding. He shows the man but he does not become the man. I say “nearly always” because once or twice the character of a sitter has dominated him so completely that a perfect fusion takes place. His portrait of Pietro Aretino [fig. 2] looks at first like a show-piece, in which he has set out to make a scoundrel appear heroic, but the longer we look at it the more we recognize the powerful intelligence and courage that Titian discovered in his disreputable friend. He has become Aretino. . . . One can look at [Titian’s portrait of Paul III at Naples] for an hour, as I have done, turning away and turning back, and discover something new at each turn. A wise old head, a cunning old fox, a man who has known his fellow men too well, a man who has known God. Titian has seen it all, and much more.4

What does “something external in a portrait” mean? What details make Aretino appear to be both a scoundrel and a hero? What are the indications of his powerful intelligence or courage? What makes Pope Paul III seem wise, cunning, and pious all at once? Although Clark has an impressive breadth of knowledge and an elegant prose style, the passage above gives no indication of how he reached his conclusions. For someone struggling to learn to think about art, Clark’s description of Titian is no help at all.

I faced precisely this problem years ago when I first became interested in studying art. I had eagerly perused Anthony F. Janson’s History of Art5 and devoured Ayn Rand’s Romantic Manifesto, which defines art and explains its crucial role in man’s life. When I first heard a lecturer applying Miss Rand’s esthetics to the visual arts, I was enthralled. Alas, I soon found that I did not yet possess sufficient knowledge to swoop from painting to painting in a museum performing that sort of analysis.

Over the course of years, I developed a series of questions to help me systematically observe the details of a painting or sculpture, and from there proceed to identify its theme and evaluate it in emotional, esthetic, philosophical, and art historical terms. In the following discussions of Holbein the Younger’s Sir Thomas More and Bellini’s St. Francis, I will walk you through this process and then leave you with a series of questions to work through on a third painting, Vermeer’s Officer with Laughing Girl.

The steps we will take to identify a painting’s theme follow. To begin, we take note of our first impressions: what strikes the eye first—or where does the eye linger, which is often the same thing—and the size of the painting. Then we identify the painting’s subject or story, which can range from a portrait of a specific historical figure to a narrative, landscape, or still life. Next we examine the objects represented: people, costumes, props, setting. After that, we consider attributes of those objects: illumination, colors, texture, sharpness of detail. We conclude by stepping back to gain an overview of the painting, including its composition (the arrangement of the objects on the two-dimensional surface of the painting), its subject, what is emphasized, and the artist’s attitude toward what he has shown. All of these observations contribute to the final statement of the theme.

At every step of this process we will note concrete details, state what effect they have on our interpretation of the painting, and set them in the context of other details in the painting. More or less frequently, depending on the complexity of the painting, we will pause to formulate a tentative theme. At the end of each study, after we make a final statement of the theme, we will consider whether that theme is in accord with all the details we observed.

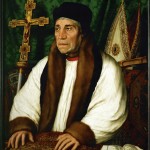

Let us begin with a fairly simple painting: Hans Holbein the Younger’s Sir Thomas More.

Holbein’s Sir Thomas More

When you first see Sir Thomas More (fig. 3), where in the painting does your eye linger: hat, face, hands, costume? In this case, the answer is the upper part of the face. (We will see why this is so when we consider attributes and composition.)

If you can arrange to stand in front of this painting at the Frick while reading this article, by all means do so. If you cannot, try at this point to visualize the size of the painting: roughly two feet square. Why is this worth noting? Because we are talking about an actual painting, not its photograph in a journal. Our interpretation of the painting would change dramatically if, instead of being just under life size, Sir Thomas’s head were two inches or twenty feet tall.

The second step in working out the theme is to identify the subject or story of the painting. When studying a portrait, we need not know the sitter’s identity or a plethora of historical facts. This is visual art; hence information has to be presented via visual concretes. When thinking about Holbein’s portrait of Sir Thomas More—as opposed to Sir Thomas More as an historical figure—our first task is not to head for the library to read about him, but to see what aspects of the sitter Holbein chose to include and to emphasize.

Having noted our first impression and identified the subject, let us turn our attention to the objects in the painting: the sitter’s face and pose, then his clothing, then the objects around him and the space he occupies.

To begin thinking about faces, it can be helpful to blurt out sets of opposites. Is Sir Thomas young or old? He appears to be somewhere in between: middle-aged. How do we know that? He has wrinkles, which usually start to appear in one’s thirties. However, wrinkles not only signal aging skin; they also suggest a person’s habitual expression. Piero della Francesca’s Augustinian Nun (fig. 4) most likely developed the deep lines that bracket her mouth from frowning incessantly. What has the man in our portrait been doing with his face? He does not have the vertical lines bracketing his mouth that the nun does, nor is he grinning from ear to ear. The crow’s feet around his eyes might have come from laughing or from squinting in order to see something. For the moment, let us just say that he appears to be a serious fellow.

Can we guess what he usually thinks about? That is more difficult, but not impossible. In Reni’s Immaculate Conception (fig. 5), the woman is obviously thinking about heaven: Her eyes are rolled upward, her hands clasped in prayer. The eyes of Sir Thomas, on the other hand, are open, focused straight ahead, and enlivened by slight glints. He is gazing not toward some supernatural dimension, but at a person or object that is visible and nearby.

Could the direction of his gaze be mere coincidence? No. An artist includes what he includes because he regards it as important; thus, in order to view a work of art objectively, we must grant importance to what he has included.6 Holbein started with a blank canvas, and had to select every detail he painted on it. Since he included the wrinkles and the glinting eyes, and gave a particular direction to the sitter’s gaze, we must treat such details as significant.

What else can we say about Sir Thomas? Is he a glutton or does he eat moderately? Is he healthy or sick? He eats moderately and is healthy: We can tell because he seems to be of average weight and has a good complexion, without broken blood vessels, pallor, or other signs of illness or dissipation.

By observing elements of the painting and asking questions about them, we have collected a string of adjectives describing Sir Thomas: middle-aged (the wrinkles), this-worldly (direction of his gaze), lively (the glint in the eye), serious (the eyes), and healthy (skin color, weight). These are the data from which we can draw our first tentative theme.

The general goal in stating the theme is to form a complete sentence that states the message of the artwork. It must be a complete sentence because a theme must identify not only the main feature in the painting, but also what he, she, or it is or does. The theme of a work of visual art can range from a statement of a person’s fundamental characteristics (for a portrait) to more general statements such as “The exploration of all aspects of knowledge by ancient Greek philosophers and scientists was a thrilling achievement” (for a complex work such as Raphael’s School of Athens). A first tentative theme of the Holbein portrait might be: “Sir Thomas More is middle-aged, this-worldly, lively, serious, and healthy.”

Our second step in stating a tentative theme is to decide which of the elements we have listed are most important. The way a person thinks has more effect on who he is and what he does than physical features such as his eye color and age do. The fact that Sir Thomas is serious and this-worldly might well explain why he is healthy; the shape of his nose cannot. Trying to pare down the theme to fundamentals, we can reduce our laundry list of characteristics to: “Sir Thomas is serious and this-worldly.” As we look at more details of the painting, we will refine this theme.

Let us turn our attention to Sir Thomas’s grooming. Caring for the handlebar mustache and goatee sported by Velázquez’s Philip IV of Spain (fig. 6) would require substantial time before a mirror or with a valet. Sir Thomas has no beard or mustache, and his hair is cut simply and left unstyled: He could wash it and leave it to dry while he attended to more urgent business. At least with respect to personal grooming, Sir Thomas is not a finicky man.

This brings us to a point I mentioned in passing earlier. When studying a painting, we must state the visible concrete and its effect. If we just say, “Sir Thomas has short black hair” and the like, without naming the effect of such facts in the context of the painting, we will never understand the meaning of the painting. For the sake of identifying the theme of a painting, it is helpful to write notes in two columns: one for the detail we have observed, and one for the effect it has. Then, when it comes time to state a tentative theme, we can read down the “effects” column to see which characteristics are emphasized by repetition, which are related, and which are most fundamental.

What else is notable about Sir Thomas’s face? A few bangs peek out from beneath his hat, making him appear slightly unkempt. The five-o’clock shadow on his chin confirms that impression. The haircut, the bangs, and the five-o’clock shadow all imply that Sir Thomas does not spend much time primping.

The inclusion of three details conveying the same point suggests that Holbein considered this a significant aspect of Sir Thomas’s character. But is Sir Thomas merely careless of his appearance, or is there another explanation? Further study of the painting should tell us.

Sir Thomas sits with shoulders back, chin up. His bearing suggests self-confidence. This is a fundamental characteristic, and it helps explain why he is not overly concerned with grooming: He is not a slob, but he is confident enough not to obsess about what others will think of him based on his appearance. Let us revise our tentative theme to: “Sir Thomas is self-confident, serious, and this-worldly.”

Turning to his clothing, the lush fur and velvet plus the massive, elaborately wrought gold chain indicate wealth. Among these the chain is the most prominent. Significantly, it is not personal adornment but a chain of office, indicating his service to the king. (The rose symbolizes the Tudor royal family.) The fact that Sir Thomas chose to wear this chain for his portrait indicates that his service to the king is very important to him. His only other jewelry is an unostentatious ring on his left hand.

Compare the outfit worn by Henry VIII (fig. 7) for his Holbein portrait. One need not be a tailor to realize that the jacket’s gathers, tucks, slashed openings, and bejeweled embroidery are the result of enormous labor and expense. In addition, the king wears a plumed hat, two rings, and a gem-studded gold necklace. Compared to such an extravagant display, Sir Thomas’s fur and velvet still look luxurious and expensive, but unobtrusively so, and his hat is downright plain. The outfit suggests that he is a man of means, but the absence of elaborate clothing and jewelry demonstrates his lack of concern to impress people with an ostentatious appearance. It thus confirms the self-confidence suggested by his posture and grooming.

Sir Thomas’s gold chain suggests another clarification. We noted before that the wrinkles around his eyes suggest that he squints a lot. Perhaps his commitment to his duties to the king explains this; that would also explain his slightly unkempt appearance. Concern with his service to the king is more specific than merely “this-worldly,” so let us modify our previous tentative theme from “Sir Thomas is self-confident, serious and this-worldly” to “Sir Thomas is self-confident and very serious about his service to the king.” Better than “serious” (which might suggest that Sir Thomas merely lacks a sense of humor), is “conscientious,” which implies hard work. So: “Sir Thomas is self-confident and is conscientious about his service to the king.”

Having considered Sir Thomas’s face and outfit, let us move on to the objects around him—which, borrowing a term from the theater, we can place under the heading of “props.” He seems to be holding a folded piece of paper, but, looking closer, it turns out to be a book—the lower corner, much darker, is below Sir Thomas’s right hand. The only other prop is a plain wooden table at our left. The simplicity and scantiness of the furniture reinforce the message suggested by the understated elegance of his clothing: He is not concerned to flaunt his wealth or status.

As our last step in looking at the objects in the painting, let us turn to the setting, the space in which the figures and objects are situated. Sir Thomas is seated in front of a simple curtain that limits the depth of the picture space, forcing us to focus on the sitter. Memling’s Portrait of a Man, by contrast (fig. 8), has a charming landscape background. No matter how interesting the man’s face is, at some point we will start peering at the details of that landscape. In Sir Thomas’s portrait, we almost do not have the option of looking elsewhere. Even the red curtain cord that hangs so casually at the upper right of the painting helps guide our gaze back to the figure. If it were gone, the lines of the curtain would lead the eye up and out of the picture. With the cord there, the eye halts and returns to the sitter’s face. So tightly is the setting constructed that as long as we look at this painting, we cannot help but look at the sitter.

Let us turn now from the objects (people, clothing, props, setting) to the attributes of those objects: light, color, and texture. In one respect, of course, subject and style are inseparable; there can be no color or texture apart from an entity possessing that color or texture. In another respect, however, color, texture, and the like properly fall under the heading of style rather than subject. Looking at a painting, we can consciously shift our focus to look at attributes rather than objects, by asking such questions as: What does the light illuminate most strongly? What colors and textures are used? How do they relate objects within the painting? What do they emphasize?

Bright light falls on Sir Thomas’s cheeks and nose, but is strongest on his forehead, which is further highlighted by contrast with his jet-black hat. Thus the brightest patches of light surround and emphasize his eyes, which here (as on most faces) are the most expressive feature. Incidentally, the five-o’clock shadow that makes him appear slightly unkempt also makes the lower part of his face darker and less shiny, which helps keep our attention on the eyes.

The painting is dominated by green, red, and brown—a combination of colors that is dark but also warm, intense, and sophisticated. The same man depicted in garish orange and purple would appear clown-like. The same man wearing a brown robe like that of St. Francis (fig. 10) might appear bland and conventional. In pink, blue, and gold (compare Reni’s Immaculate Conception, fig. 5), he might seem insipid, verging on saccharine.

The presence of certain colors is not all we ought to consider; their qualities can be equally important. Clearly there is a difference between the red and green in Gilbert Stuart’s George Washington (fig. 9) and the red and green of Holbein’s Sir Thomas More. To describe that difference precisely requires technical terminology. Although we may call both “red,” a ripe strawberry has higher saturation (i.e., intensity of color) and higher value (i.e., closer to white than to black) than a bing cherry. In the Stuart painting, the reddest red and the greenest green have low values and are not highly saturated. That helps make Washington seem somber and serious. The fact that Sir Thomas dares to wear highly saturated colors (and for a formal portrait, no less) adds, subtly, to our knowledge of his character.

Although colors are important, their significance depends on their relationship to the other elements of the painting. Any color or combination of colors—in fact, any detail of a work—must be considered with respect to the context of the work as a whole. Depending on the other elements in a painting, a combination of green and red might evoke rose gardens or Christmas; an apple might recall the Fall of Man or New York City.

Analyzing a painting is an inductive process, not a deductive one. We do not start with a list of objects, attributes, and rules, and figure out what the painting must mean by reading across Line Q to Column 3. Rather, we begin by observing concretes, noting their effects, and combining the effects into a perceptually grounded interpretation of the artist’s message, continually stepping back to consider each detail in the context of the whole painting.

Let us return to the portrait of Sir Thomas More. As we noticed earlier, his skin tones are healthy. When we focus specifically on the colors in the painting, however, we see a substantial amount of red around his eyes. While checking a late draft of this article against the actual painting at the Frick, I was surprised to notice how much darker the under-eye circles are in the original than in the photograph I had been using for reference. Although photography and print technology have made tremendous strides in the past few decades, the painting itself always has details that the best photographic reproduction cannot capture.

The redness and the dark circles make Sir Thomas appear somewhat tired, and combined with the prominent chain of office, they indicate a man who is not only conscientious about his service to the king, but is wearied by it.

Some green underlies Sir Thomas’s stubble. The red and green repeat the main color scheme (i.e., that of the clothing and curtains)—or, to be more precise, the main color scheme echoes the colors in Sir Thomas’s face. Not coincidentally, the green curtain and red-sleeved jacket are sharply set off from Sir Thomas’s face at every point by his hair, hat, and collar. If his face were not set off this way, the green and red used elsewhere in the painting would overpower the colors in his face rather than subtly emphasize them.

Turning to the textures, observe that the lush velvet and fur of Sir Thomas’s costume and the glittering gold of the chain are portrayed in realistic detail and provide additional information about their wearer. First, they tell us Sir Thomas is wealthy. The same style and color clothing in plain wool or linen would not convey the same message. Second, the textures help set off his face, which is slightly shinier than the objects surrounding it. Under “first impressions,” at the beginning of this analysis, we noted that when looking at the painting, our eyes came to linger on the face. This effect is largely a consequence of Holbein’s masterful use of light and texture to steer our eyes in that direction.

At this point in our study, what can we state as a tentative theme? Given the luxurious but subdued color and texture of his clothes, we should add that he is well dressed in an understated way—he is not obsessed with his appearance, but neither is he unconcerned with it. So: “Sir Thomas is self-confident, unostentatiously elegant, and conscientious about his service to the king.”

As the final step in our study of this Holbein portrait, let us step back for an overview of the painting. For contrast to its composition (the arrangement of the objects), compare Memling’s Portrait of a Man (fig. 8). In the Memling portrait, the sitter’s shoulders fill the width of the canvas. Against the dead black of the coat that fills the lower half of the painting, only the man’s hand, holding an unidentifiable object, stands out. In the Holbein, the arms and shoulders slope upward into a triangle, drawing attention to the head (and thereby the face) at the top of the triangle. The wide fur collar forms an inverted triangle that points to Sir Thomas’s hands. Together these two triangles lead the eye back and forth between the two features most indicative of character: the face and hands. Now, looking specifically at the face and hands, we see they are also linked by the repetition of flashes of white: eyes, collar, cuffs, book. Since white appears nowhere else in the painting, this repetition also serves to emphasize the face and hands.

By focusing intensely on Holbein’s Sir Thomas More, we have observed many details and effects, but we can notice even more by comparing this painting with a work on a similar subject, or by the same artist, or both.

Consider Holbein’s William Warham, Archbishop of Canterbury (fig. 11), painted at nearly the same time as Sir Thomas More. The faces of the archbishop and Sir Thomas are both shown in three-quarter view (halfway between profile and full face, with both eyes and one ear visible). Their black hats and fur-collared robes are similar. But they are not shown with similar characters.

The archbishop is much older: His hair is gray, his face and neck bear a multitude of wrinkles, and his skin is dull. His mouth is much paler than Thomas’s, hence less visible. The heavy-lidded eyes combined with the straight-lipped mouth make him appear aloof and disdainful.

Looking back at Sir Thomas, we note that although he is not smiling, in comparison with the archbishop he appears as though he is about to smile. The corners of his mouth are turned up slightly, even in repose. (To see this more easily, use one hand to cover all his face except his mouth.) The incipient smile adds a detail about Sir Thomas’s character that we have not yet mentioned. Although, at first glance, it might suggest that he has a sense of humor, since the smile is so slight, perhaps a better description is that he projects an air of benevolence. The world has made him smile before, and he seems to assume it will do so again. The subtle curve of the mouth is a detail we could easily have missed had we not compared Sir Thomas with another portrait.

What else can we learn from studying the archbishop’s portrait? Generous fur cuffs draw attention to his hands, which are spread wide (almost claw-like) on a gold brocade pillow. Imagine for a moment that Sir Thomas’s hands were shaped and positioned like those of the archbishop. How would our “reading” of Sir Thomas change? He would appear less self-contained. Sir Thomas’s hands, quietly holding a book, indicate calm and self-possession.

What else can we say about the archbishop? He wears a white robe, probably clerical garb. The mere color suggests wealth and leisure, and this suggestion is amplified when we consider that white was an impractical color in an era when cleaning clothes was time-consuming and expensive. Like Sir Thomas, he has a fur collar, but the fur is not V-shaped. Instead it runs in two vertical bands from his face to his hands, drawing the eye to both. The fur collar and the gold brocade pillow also suggest wealth, and the items surrounding the archbishop—the regalia of his clerical office—suggest wealth and power. First, the green backdrop has an elaborately woven pattern. In an age when fabric was laboriously loomed by hand, such fabric was very expensive. More obvious indications of wealth are the elaborately wrought, bejeweled crucifix at the left and the bejeweled miter (archbishop’s hat) at the right. Below the miter are two gilt-edged books, and at the lower right is an open book on some ecclesiastical topic—the word “Patriarchal” is visible. The book and the pillow function as a barrier between the archbishop and us. Sir Thomas, with only a small table at one side to rest his elbow on, seems much more accessible. Also, Sir Thomas’s book is plainly bound, without gilt or jewels, suggesting that it is more for use than for display. The archbishop is a wealthy, aging, aloof man who has accumulated substantial clerical power in an age when high-ranking clergymen still wielded temporal power as well. Sir Thomas, by contrast, is high-ranking but approachable and unostentatious, and he has a sense of benevolence that is lacking in the archbishop’s face.

In each case, the artist’s selectivity—what he chose to include, and thus what he has presented as important—is his means of expressing the message in the painting.

To underscore this point by way of contrast, consider that if you took a photograph of me while I was listening to the evening news, you could certainly catch a grim expression on my face. While a photograph captures any fleeting expression, any passing gesture, any random moment, a painting is another matter. An artist selects every element that goes into a painting. He does so on the basis of what he regards as important, what message he wants to convey, and which details will best convey it. In the case of a portrait, the message consists of an evocation of the most significant features of the sitter’s character (real or imagined) as selected by the artist. If Holbein chose to show the archbishop’s face, hands, clothing, and surroundings in this particular way, it was because Holbein thought they would indicate important aspects of the archbishop’s character. Everything in art matters.

Let us sum up Holbein’s portrait of Sir Thomas More. The subject is a wealthy, healthy man of middle age. He carries himself with self-confidence (elegant but unostentatious clothes, low-maintenance hair) and has a benevolent outlook. The greatest emphasis, however, is on his service to the king: He prominently displays his chain of office, and appears weary from his duties. To our previous tentative theme we need only add a reference to his benevolent outlook: “Sir Thomas is self-confident, benevolent, unostentatiously elegant, and conscientious about his service to the king.”

When attempting to state a theme, we must be wary of making it too narrow or too broad. “Sir Thomas is wearing a velvet coat with a fur collar and has a five-o’clock shadow” is too specific. It tells us nothing about the sort of person the sitter was—what he thought or how he acted. “Service to one’s country is important” is perhaps a statement Sir Thomas would agree with, but as a statement of the theme of this painting it is too broad. This is a portrait of a specific man, not a lesson in politics or ethics.

As I said when we first attempted a tentative theme, if the theme is properly stated, it should capture the essence of the painting. Our final theme fits every detail we have noted, from Sir Thomas’s hat to his hands, from the colors to the composition.

An Historical Note on Sir Thomas More

The message of a painting must be conveyed by visual means, but now that we have examined Holbein’s Sir Thomas More in detail, let me offer a brief historical summary of More’s life, which supports our observations.

You may remember Sir Thomas More as the hero of Robert Bolt’s A Man for All Seasons. He was indeed a conscientious royal servant, serving Henry VIII as lord chancellor of England from 1529 to 1532. During that time Henry was attempting to divorce his first wife, Catherine of Aragon, in order to marry Anne Boleyn. When the pope refused to annul the marriage, Henry established his own church, named himself its head, and granted himself a divorce. Sir Thomas quietly but persistently refused to swear an oath to Henry as head of the Church of England. In 1535, eight years after this portrait was painted, he was beheaded for high treason. “I die as the King’s true servant, but as God’s servant first,” said More on the scaffold. Whatever one’s political or religious position, one cannot but admire his adherence to what he considered right and true. His conscientiousness is certainly displayed in Holbein’s portrait of the man.

Bellini, St. Francis in the Desert

We turn now from Holbein’s Sir Thomas More to a much more complex painting, Giovanni Bellini’s St. Francis in the Desert (fig. 10). Again we begin by asking: Where do our eyes go first?

Once in a while a feature of the painting that the artist did not emphasize may draw your attention: for example, a face eerily reminiscent of your ninth-grade algebra teacher. In most cases, however, the eye first lingers on the person or thing that the artist emphasized. If we propose a theme that does not prominently feature that person or thing, the proposed theme is likely to be wrong. When studying a painting such as this one, which incorporates figures and extensive landscape, we can easily forget what struck us at first glance—hence we must explicitly identify it. My eye went first to the figure of the man in the foreground.

We also need to establish the painting’s scale, since we are studying a photograph rather than the original. This painting is approximately four by five feet (49 x 56 inches). The man in the foreground is about twenty inches high, less than half life-size.

Bellini’s painting represents not only a specific man but a specific event. Identifying the particular event—that is, identifying the subject of the painting—requires knowledge of the life of a Christian saint. This raises an interesting question. Since a work of visual art must present its message by visual means, does the fact that we must know about St. Francis’s life in order to identify the subject diminish Bellini’s painting as a work of art?

In a word: no. The accumulated stories of Western civilization, including Greek mythology, European history, and the Judeo-Christian tradition, were for millennia shared by everyone—artists and their audiences included. Only in the past half century, with the advent of progressive education and multiculturalism, has such knowledge come to be considered arcane and unnecessary. If you were unfortunate enough to have been educated by teachers who failed to teach the history of Western civilization, a side benefit of studying the art of ages past is that it provides a fascinating way to introduce yourself to aspects of that rich history.

Using references to this common Western heritage enables an artist to portray a much broader range of themes than would be possible if he depicted only that which is universally recognizable. If an artist and his viewers both know the story of David and Goliath, for example, the artist can use the figure of David to comment on how and why a young boy might defeat a much older and stronger adversary: by speed and single-mindedness (Bernini’s David), by thought (Michelangelo’s David) or with God’s help (Donatello’s later David). If the artist could not count on the viewer’s knowledge of the story of David and Goliath—if he could show only a generic figure of a teenage boy—then his theme would be limited accordingly.

Understanding part of the legend of St. Francis enables a deeper understanding of the powerful and complex message in Bellini’s painting. What, then, is the subject?

The central figure is St. Francis of Assisi (1182–1226), identifiable by the type of monk’s robe he wears and by the small marks on his hands and feet. According to his biographers, in 1224 St. Francis spent forty days praying and fasting in the wilderness, at which point he had a vision of Christ and an angel, and was imprinted with the stigmata, marks of the wounds inflicted on Christ’s hands, feet, and side when he was on the cross. Although the mere mention of stigmata makes my palms twitch, this painting has always attracted me. Until I studied it in detail, I was puzzled and somewhat annoyed by that attraction, but having identified the reasons for it (which I’ll mention later), I see that my fondness for it is rooted in rational values.

Let us begin our study by examining the objects in the painting, starting with the prominent figure of St. Francis, at the right. He is tall and slender. Compare him to a figure such as Holbein’s Henry VIII (fig. 7), and the effect of the proportions becomes clear: The tall, gaunt figure looks more “spiritual” than the shorter, rotund one. St. Francis appears not to have been eating much—a visual reminder of his asceticism.

What is St. Francis doing? He stands with his head back. Each of his out-flung hands displays a stigma. One foot, pushed forward, displays another stigma. His head is tilted back behind the line of his spine. Stand as he does and you will feel as if you are about to topple backward. The stance indicates that St. Francis is startled: He steps back, off-balance mentally as well as physically.

His face is shown in three-quarter view. Because of that, we can almost see whatever St. Francis is gazing at so raptly—it is just out of range of our peripheral vision. Were he shown in full frontal view, whatever he sees would be behind us and not even close to our range of vision. Were he shown in profile view, we might actually see what he sees, off at the left of the painting. But we cannot see what he sees—only its effect on him. In a moment we will see why this absence is appropriate for this painting.

We can surmise the object at which St. Francis is looking because his chin is raised and his gaze directed upward, like that of the Virgin in Reni’s Immaculate Conception (fig. 5). His mouth is slightly open, confirming the fact (already noted from his posture) that he is surprised and startled. The heavy shadows on his cheeks reveal his gauntness, reminding us again of his asceticism. By this point in the story, St. Francis had been fasting for nearly six weeks.

Even St. Francis’s hair helps indicate his character. Its short length requires little maintenance. In comparison with a figure such as Philip IV, who wears a high-maintenance mustache and beard (fig. 6), St. Francis comes across as a man unconcerned with his physical appearance. On the other hand, he has only stubble of a beard, certainly not the forty days’ growth he would actually have, had he been in the wilderness praying all day long. Why? Bellini selects details that will convey his message, rather than details that will naturalistically represent St. Francis. A full beard would obscure St. Francis’s gauntness and his startled expression—hence, no beard.

So far in this painting, two points about St. Francis are emphasized: that he lives ascetically (his gaunt face and body) and that he is startled by what has happened (open mouth, backward step). These two are intimately connected. Being pious and ascetic does not guarantee that God will favor you. (Christians are not supposed to “trade” with the deity.) Our first tentative theme must mention both the asceticism and the surprise: “St. Francis, gaunt from fasting in the wilderness, is startled to receive the stigmata and to be granted a vision.”

Let us turn to St. Francis’s clothing. He wears a monk’s robe with a rope belt, which might indicate poverty, asceticism, or both. The robe covers his body, revealing only his face, hands, and one foot. By hiding the rest of his body, the robe helps emphasize what we can see: his expression and the stigmata. The position of the folds reveals St. Francis’s posture and indicates that his left knee is bent, his right leg straight, his chest tilted back from the waist. Hence we know he is leaning as well as stepping backward.

Although the usual Franciscan habit is of coarse, dark brown cloth, the robe in this painting is light brown and smooth enough to reflect the light. Its color and texture help draw attention to St. Francis by making him stand out from his surroundings. Imagine him in a robe as dark as the grass near his feet: He would blend into the background. St. Francis’s clothing therefore has two important effects: Its folds emphasize his posture and the stigmata, and its color sets him off from the landscape around him.

What can we add to our first tentative theme, “St. Francis, gaunt from fasting in the wilderness, is startled to receive the stigmata and to be granted a vision”? His clothing emphasizes his asceticism, the stigmata, and his startled reaction. Since our first attempt includes all that, let us turn to the props.

At the right, a plain lectern supports a thick book expensively bound in red leather. In the Middle Ages and in connection with St. Francis, this must be a Bible. Its prominent presence reminds us that St. Francis has been studying the word of God. A skull atop the lectern shows that he has been meditating on mortality. Behind the lectern is a narrow cross topped by a crown of thorns, a reminder of Christ’s suffering and death. Clearly St. Francis is not only extremely ascetic but also extremely pious.

To the left of the lectern is a cave entrance with a gate. Why put a gate on a cave? Because otherwise we might think that the cave is merely a cleft in the rock. The gate tells us that St. Francis has been living in that cleft in the rock, a fact that provides further evidence of his asceticism.

On the ground behind St. Francis stands a pitcher, but no food or eating utensils are in sight. The cute rabbit peeking out from the rocks directly below St. Francis’s right wrist is yet another reference to his fasting. Had I been alone and hungry in the wilderness, the rabbit would soon have become stew. St. Francis has been fasting for forty days, but the rabbit remains alive and fearless. The pitcher and the rabbit combine to emphasize St. Francis’s asceticism yet again—particularly his enormous self-control in ignoring physical needs and discomfort.

In the background appear two more animals, a donkey and a crane. In Christian lore, the crane represents vigilance and loyalty. According to a charming story related in medieval bestiaries, every night several cranes were chosen to guard their king while he slept. Each would stand on one foot, clutching a rock in the other. If he fell asleep, the rock would fall, hit his other foot, and wake him up.

The donkey sometimes represents stupidity and obstinacy. However, an ox and an ass are usually shown in the background of representations of the nativity, where they are worshipful admirers of the newborn Christ child, somehow aware of his divine nature. In Bellini’s painting, the crane and the donkey are looking in the same direction as St. Francis. They gaze to our left, toward St. Francis’s vision, which they can probably see since they have not been corrupted by the possession of reason—that direst of impediments to mystical vision.

Scanning the background carefully, we notice that although St. Francis is the most prominent human figure present, he is not the only one. In the distance on the left, below the olive tree and the largest city tower, a shepherd tends his flock. Sketched in shades of gray, he is difficult to see, but his behavior is significant. The shepherd does not look toward the vision: He stares at St. Francis. This confirms the idea that the insufficiently faithful are not granted mystical visions. The shepherd performing his mundane job has not practiced the piety and asceticism that St. Francis has practiced, and therefore he does not see what St. Francis sees.

How shall we tweak our tentative theme to incorporate what we learned from studying the shepherd and the animals? The objects on the right side of the painting, near St. Francis, show what he is doing: fasting, sleeping in a cave, reading the Bible, meditating on Christ’s suffering and death. In other words, they indicate his extreme piety and asceticism. On the left, the animals and the shepherd introduce the idea that, when it comes to having a mystical vision, being an unreasoning animal is better than being a thinking human being. Our previous attempt at a theme was: “St. Francis, gaunt from fasting in the wilderness, is startled to receive the stigmata and to be granted a vision.” Let us revise that to: “After living ascetically and piously in the wilderness, a startled St. Francis is granted the stigmata and a vision that reasoning men cannot see.”

But if that is the theme, why is a third of the painting devoted to a wondrously beautiful landscape that includes cultivated fields and city towers? Why not simply show St. Francis having his mystical experience in the sort of wilderness his biographers describe?

To answer this question, let us consider the details and effect of the setting. The rolling hills at the left, presented in exquisite detail, include at least four separate walled cities or castles, conspicuous for their color, size, and crisp lines. The vividly blue sky is dotted with fluffy white clouds. The sun blazes down. It is a glorious day on earth, and earth is the dominant feature in this section of the painting: The horizon line is so high that little sky appears. Yet St. Francis dominates the landscape, by his position in the foreground and by the fact that his part of the landscape—the barren cliffs—occupies two thirds of the painting.

St. Francis’s domination of the scene sets up a vivid contrast: the cities versus the cave; the fields, where food is being raised, versus St. Francis’s water jug; thriving life versus gauntness and death. The charming landscape makes St. Francis’s renunciation of the world more striking by contrast. St. Francis’s figure alone could not convey this message.

Our previous tentative theme was, “After living ascetically and piously in the wilderness, a startled St. Francis is granted the stigmata and a vision that reasoning men cannot see.” Now we can add the strong contrast with the world St. Francis is rejecting. The contrast makes the theme more emphatic: This earthly glory is what you must reject, and this will be your reward.

With the rejection of earthly life in mind, it occurs to me that St. Francis’s reward is not to share Christ’s glory (no mortal man could), but to share his pain. Our earlier tentative theme was adequate, but based on the details we have just seen, it should be more emphatic: “St. Francis rejected his own mind and all the beauty of this world to live piously and ascetically, and was granted indescribable mystical visions and allowed to share Christ’s suffering.” Notice that I have stated the theme in a way that does not reflect whether I agree or disagree with it. Philosophical evaluation properly comes after the identification of the theme. Our goal here is simply to state the painting’s message as clearly as possible.

Having observed the objects in the painting (the human figures, their costumes and props, and the setting) let us turn to the attributes: light, color, texture, sharpness of detail.

The illumination comes strongly from the upper left, from a source outside the painting. It pours down like bright sunlight on the cliff and the walled cities. However, because St. Francis is looking in the same direction, the light may also be symbolic of his divine vision. The most intensely lit areas in the painting are on St. Francis’s robe and on the lectern holding the Bible, which emphasizes and visually links his mystical vision with his piety and asceticism.

What about the use of color? St. Francis’s skin tones are unhealthy, with deep brown in the hollows of his cheeks and his eye sockets sunken. The color emphasizes the gauntness that comes from fasting. (Compare his color to the healthy pink in the face of Velázquez’s Philip IV, fig. 6.) The brown also links St. Francis closely to the cliffs around him, where only neutrals appear: beige, brown, gray, dark green. These colors set off St. Francis’s austere, ascetic area from the thriving and prosperous area at the left, depicted in earthy reds and browns, with a vividly blue sky.

The textures everywhere in the painting—cloth, plants, rocks, walls—are carefully delineated. Objects appear clean, sharp, precise: brilliant and icy clear, not as if seen through a mystical haze, as one might expect in a painting depicting a religious revelation. The donkey, St. Francis, and the lectern seem to be in slightly sharper focus than the objects surrounding them. This subtly helps draw attention to them, in the same way that one’s eye is drawn to the part of a photograph that is most sharply in focus.

Our observations of such attributes make the message of this painting even more emphatic. St. Francis rejected reason and the joys of life on earth; he concentrated on the Bible and death, and God granted him a vision. The previous tentative theme still covers this: “St. Francis rejected his own mind and all the beauty of this world to live piously and ascetically, and was granted indescribable mystical visions and allowed to share Christ’s suffering.”

Finally, we step back and look again at the painting as a whole. Its composition—the way the objects are arranged on the canvas—is remarkable for the way it focuses attention on St. Francis, a relatively small figure standing off to one side. How did Bellini manage that? In the foreground, the arrangement of the cliffs leads the eye in a long diagonal from the lower left corner upward to the right. The diagonal is emphasized by the thick grass on top and ends directly above St. Francis’s head. Covering the grass with a finger makes it clear how this dark diagonal helps draw the eye to St. Francis’s head. The cliff above him has mostly vertical lines, which lead the eye down toward St. Francis. Imagine the difference if the lines were horizontal: Your eye would go back and forth rather than to the figure standing below. The brightest light on the cliff face appears directly above St. Francis’s head. In these and other subtle ways, the artist has directed our attention to a figure that occupies only a small part of the painting.

Consider also the perspective Bellini provides us. In Velázquez’s Philip IV of Spain (fig. 6), the king looks disdainfully down his royal nose at us. By contrast, we are looking down on St. Francis’s shoulder. St. Francis was famous for his humility. We are subtly reminded of that simply by the fact that we look down on him, rather than up at him.

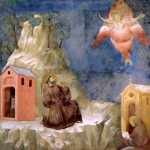

For contrast, let us compare a version of the stigmatization of St. Francis by Giotto that was painted some two hundred years earlier (fig. 12). Giotto depicts a kneeling St. Francis: awestruck, humble, frightened. Because St. Francis’s vision (a six-winged angel) appears in Giotto’s painting, we, too, can see it. The landscape is rocky and barren, with a church, another small building, and a few straggly trees. No earthly splendor reminds us what St. Francis has given up to achieve this moment. Finally, in the Giotto another monk is present. St. Francis’s biographers recorded that he went into the wilderness with a group of monks. Giotto incorporates a fellow monk who is oblivious to the presence of the angel, thus stressing that not even being with St. Francis and doing what he did is necessarily enough to be granted a vision. In contrast with Giotto, then, Bellini shows us what must be rejected and stresses how isolated and how unique St. Francis is in his piety and asceticism.

Now let us summarize. The subject of the painting is the stigmatization of St. Francis. The emphasis is on St. Francis’s asceticism and piety and his rejection of the beauty and comforts of this world. His vision and his stigmatization are presented as a sublime experience by the light, by the scintillating sharpness of detail, and by St. Francis’s expression of awe. What can we state as a final theme?

In the comparison with Giotto, we noted the strong contrast with the world St. Francis is rejecting, St. Francis’s solitude, and the fact that those who have not practiced extreme piety and asceticism are not granted sight of the vision. The theme, then, is quite emphatic. We can modify our previous theme slightly to reflect this: “St. Francis intransigently and incessantly rejected his own mind and all the beauty of this world to live piously and ascetically, and was granted indescribable mystical visions and allowed to share Christ’s suffering.”

Evaluation

We can enjoy art without being able to define what art is. In order to judge it, however, we must know art’s nature and function; we must know what it is and what purpose it serves. In this sense an artwork is like any other man-made object. One cannot evaluate a shovel, a USB cable, or dose of Vicodin without knowing what it is designed to do.

The function of art is directly related to the fact that it conveys metaphysical value-judgments. Although many men never achieve an explicit philosophy, everyone develops subconscious assumptions about the nature of man and reality. Visual art presents such assumptions in concrete, perceptual form.

What good is that? Well, in addition to being a source of contemplation and joy, art is a source of inspiration and spiritual fuel. Suppose you are vacillating between alternatives regarding a difficult matter. You cannot hold in the forefront of your mind all the principles and values that you have come to accept over the course of decades. But you can hold the image of Huntington’s Cid, Holbein’s Sir Thomas More, or Bellini’s St. Francis (figs. 1, 3, 10). With those in mind, you might be reminded to face your difficult problem with raw courage, with conscientious thought, or with humble acceptance. The metaphysical value-judgments those paintings embody can help you vividly recall which principles and values you cherish, and thus help you make a choice that will assist you in achieving those values.7 Art satisfies a philosophical need that a hefty philosophical tome cannot. That is art’s function.

Based on that function, one can evaluate art in several different ways. In “Getting More Enjoyment from Art You Love,” I showed how to evaluate a sculpture by reference to the emotions it evokes, the philosophical premises it implies, its style, the moral character of the person represented, and its importance in the history of art. Let us briefly review these types of evaluation and see how Holbein’s Sir Thomas More and Bellini’s St. Francis fare when judged according to them.

Emotional Reaction

An emotional reaction is the first and most immediate way to judge an artwork, and often the only judgment we bother to make. Long before we can identify its theme, we react almost instantaneously to a painting. That reaction is a consequence of two elements: the painting’s contents—including the metaphysical value-judgments implied therein—and our own values, experiences, and associations. When we find an artwork whose metaphysical value-judgments agree with our own most basic premises, we have an invaluable means to reaffirm our convictions, what we stand for, and what we want to pursue in life.

My emotional reaction to Sir Thomas More is positive because he is shown as the sort of person I admire and like to deal with: this-worldly, conscientious about his work, and benevolent.

My reaction to St. Francis is positive only because of that gorgeous landscape on the left side of the painting. The rolling hills remind me vividly of a recent train ride through northern Italy, and the style reminds me of other paintings done during the Italian Renaissance—one of my favorite historical periods. My emotional reaction has little to do with the metaphysical value-judgments expressed in Bellini’s painting. If you have different associations with this sort of landscape and with the Renaissance, your emotional reaction may be radically different—and equally appropriate.

Judging Content

Judging the content of a painting philosophically requires identifying its theme and then considering the ideas it depicts and implies, all the way down to the most fundamental level, the metaphysical value-judgments. It involves asking and answering the questions: What does this painting imply about the world, about man, and about what is possible to man on earth—and is the message conveyed thereby supportive of human life?

The theme of Sir Thomas More is “Sir Thomas is self-confident, unostentatiously elegant, and conscientious about his service to the king.” This implies (among other things) that this world is important, that doing one’s work well is important, and that a man can earn the right to a good opinion of himself. Such metaphysical value-judgments are life-promoting. Hence, philosophically, we can judge Holbein’s Sir Thomas More as a positive work.

The theme of St. Francis is “The man who intransigently and incessantly rejects his own mind and all the beauty of this world to live piously and ascetically may be granted indescribable mystical visions and allowed to share Christ’s suffering.” This theme implies that this world is beautiful but unimportant; that what is important lies beyond this world, in another dimension; that a dichotomy exists between man’s mind and his body, and that his body must be punished for the sake of his spiritual development. Such metaphysical value-judgments are contrary to the requirements of human life on earth; thus we can judge St. Francis as philosophically bad, despite the fact that it is esthetically good.

Judging Style

Judging a painting in esthetic terms (as a work of art) involves focusing on how the painting is executed, rather than what it says. The function of visual art, as we have seen, is to present a view of what is important in the world in concrete, perceptual form. Hence the first question when judging a painting’s esthetic merit: Is the artist’s theme conveyed so clearly that we cannot fail to grasp what he is trying to say? Sir Thomas More and St. Francis both provide numerous unmistakable clues as to the nature and character of the figures depicted, what they are doing (or have done) and why, and what is meant by the unified whole.

The second question when discussing style is the flip side of the first: Is the work well integrated, without extraneous, distracting details? If attentive study of a painting reveals apparently inexplicable details, eventually those details will distract us and diminish the artwork’s emotional and intellectual impact. As soon as we start wondering what an artist was thinking when he included that puzzling detail, we are no longer in his world “hearing” his message; we have crossed from the world of art into the realm of psychological speculation.

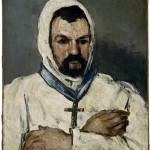

With the function of art in mind, we can easily explain why, in esthetic terms, Holbein’s Sir Thomas More is better than Cézanne’s Portrait of the Artist’s Uncle as a Monk (fig. 13). In the latter, the oversized brushstrokes and an asymmetrical face are distracting. Just as badly written prose makes it difficult to follow an author’s train of thought, Cézanne’s style makes it difficult to grasp whatever metaphysical value-judgments he was attempting to convey. The Bellini and Holbein paintings, by contrast, are both superb in esthetic terms: Every element contributes to and reinforces their themes.

Moral Evaluation of the Person Represented in a Portrait

Evaluating a painting as a work of art does not require that one do biographical research on the figure represented and evaluate his life and ideas philosophically. But if curiosity about a particular figure overcomes you, and you have the time to research him, it can be well worth doing so. Find out what the person was famous for and what principles he lived by. What were his values? What virtues did he practice? According to your own ethical standards, was he good, evil, or mixed? Judged by the standards of his own professed philosophy or his own time, how would he fare? Even for mythological figures or historical figures that have become nearly legendary (such as the Cid, discussed in “Getting More Enjoyment from Art You Love,” p. 123), one can usually discover what aspects of character and what actions the figure is famous for, and then evaluate him.

Sir Thomas More (1477/8–1535) was one of the earliest humanists in northern Europe. That is, after a thousand dark years in which theology was regarded as the ultimate “science,” Sir Thomas was among the first to consider man a subject worthy of study. He was also, however, a devout Christian—so devout that he was willing to face death rather than take an oath that he considered morally wrong. In addition, Sir Thomas was the author of Utopia, in which he attacked the political and social evils of his time—advocating instead a communistic ideal modeled in part on Plato’s Republic and the culture of ancient Sparta. Here is Sir Thomas on the relationship between famines and wealth:

Consider any year, that has been so unfruitful that many thousands have died of hunger; and yet if, at the end of that year, a survey was made of the granaries of all the rich men that have hoarded up the corn, it would be found that there was enough among them to have prevented all that consumption of men that perished in misery; and that, if it had been distributed among them, none would have felt the terrible effects of that scarcity: so easy a thing would it be to supply all the necessities of life, if that blessed thing called money, which is pretended to be invented for procuring them was not really the only thing that obstructed their being procured!8

The facts about Sir Thomas’s life and philosophy that most affect one’s moral judgment of him depend on one’s own ethical and political standards, and on what aspect of Sir Thomas’s character one focuses one’s attention. Although Sir Thomas’s willingness to die rather than surrender his convictions counts to some extent in his favor, his advocacy in Utopia of collectivism—which has caused massive suffering and death throughout history—outweighs his otherwise heroic stature in my mind.

St. Francis (1181/2–1226), spurning his wealthy family, founded a monastic order devoted to obedience, poverty, and chastity. His preaching and the influence of the monastic order he established have been credited with helping turn the focus of late medieval art from depictions of supernatural beings to depictions of life on earth—specifically, the lives of the Virgin, Christ, and the saints. In this sense, St. Francis’s work unwittingly helped to pave the way for the secular paintings of the Renaissance.

Although St. Francis encouraged followers to study the lives of the saints and to do God’s work on earth, he was devoutly opposed to earthly pleasures. When assailed by temptation, he would throw himself naked into a ditch full of snow or roll in a briar patch. He dubbed his body “Brother Donkey,” which adds another layer of meaning to the donkey that appears in Bellini’s painting.9

Evaluating a person on moral and political grounds is emphatically not the same as evaluating a portrait of that person. Why? Because an artist may decide to emphasize aspects of a subject that were not prominent in the subject’s life. Bellini, for example, emphasized St. Francis’s piety and asceticism rather than his youthful rebellion or his love of animals. Holbein emphasized Sir Thomas’s conscientious service to Henry VIII rather than his ventures into political and economic theory.

Art-Historical Evaluation

Art-historical evaluation of a painting requires extensive knowledge of other paintings, as well as the sort of comparisons that can be made only with reams of photographs. To evaluate the importance of Holbein the Younger (1497/8–1543) and his Sir Thomas More in the history of art, we would have to study portraits from ancient times to the present, especially those from the Renaissance. Did Holbein’s work introduce major innovations in subject, style, or theme? Was it an uninspired adaptation of another painter’s work, or an original effort?

In fact, Holbein is regarded by many art historians as the greatest European portraitist of his time, because of his superlative ability to capture both physical appearance and character. It is an interesting sidelight that among the dozens of top-notch Holbein portraits that have come down to us, Sir Thomas More is one of only a few that portray a sitter so sympathetically that we assume Holbein himself must have liked him.

As for Giovanni Bellini (ca. 1430–1516), he came from a family of noted Venetian painters who during the 15th century helped make Venice an artistic center rivaling Florence, the birthplace of the Renaissance. Painters such as Masaccio used landscape largely as a backdrop, albeit a charming one. Bellini was one of the earliest painters successfully to integrate figures and landscape, making the landscape contribute to the stories he told rather than merely using it to provide a backdrop. The juxtaposition in St. Francis of the bare cliffs with the thriving countryside and walled cities is a brilliant example. In terms of the history of art, Bellini is also important for his influence on subsequent painters: Among his students were Giorgione and Titian.

Vermeer, Officer and Laughing Girl

Although anyone can learn to do the sort of detailed analysis we have done for Holbein’s Sir Thomas More and Bellini’s St. Francis, it does require both practice and considerable mental effort. To help you along, I offer below a series of questions (but no answers) for a third painting: Vermeer’s Officer and Laughing Girl (fig. 14).10 As you work through these questions, bear in mind that your goal is to state the theme of the painting—the artist’s message to you—by means of observing the details, stating their effects, and judging the relationships between them. To get the most benefit from this exercise, I recommend that you jot down the details as you notice them in one column, and, in a second column, their effect.

First impressions

Where does your eye go first—to what figure or what part of the painting—and why?

The painting is 20 x 18 inches. Work out what size, approximately, the girl’s face is: life size, less than life size, or more than life size?

Subject / Story

In general terms, what are these two figures doing: sitting, standing, talking, or something else? Can you place these figures in an historical context? Do they seem to represent a specific narrative: a myth, a biblical story, an historical event?

Objects

Look at the man. You can hardly see his face: What is the effect? Can you read his expression? What is he looking at? If you saw him in profile view or three-quarter view (like Sir Thomas, fig. 3 ), how might your interpretation of him differ? Given that, can you be more specific about the effect of the head position that Vermeer chose to use?

The man’s right arm is akimbo. What attitude or emotion does that suggest? He is seated in the foreground and is much larger than the girl. What is the effect of this? How would your interpretation of his personality and behavior be different if he were seated across the table from the girl and were the same size? What if he were resting his clasped hands on the table?

What do the man’s hat and coat tell you about his character? Is he sedate, swashbuckling, businesslike? Compare his costume to that of Washington or Philip IV of Spain (figs. 9, 6). Which costume details indicate this man’s character? How would your interpretation change if he were hatless, wore a plain black cap like that in Sir Thomas More (fig. 3), or a bejeweled one like that in Henry VIII (fig. 7)?

In a series of adjectives or phrases, sum up what you know so far of this man’s physical appearance, character, and current action. If you’ve been jotting down details and their effects, you should be able to read these adjectives off from the “effects” column. Are there any characteristics that are emphasized by being shown in different ways? Are there any characteristics that seem more fundamental than others—that help explain the others?

Now turn your attention to the girl. One important difference between her and the man is that you can see her face. Based on portraits such as Holbein’s Sir Thomas More (fig. 3) or Velázquez’s Philip IV (fig. 6), do you think this is a portrait?

Where is the girl’s gaze directed? How does she feel about what she sees? What details of her face tell you that? Compare her eyes and mouth with those of the Augustinian Nun or Reni’s Madonna (figs. 4, 5). Based on her posture and the position of her hands, is she tense or relaxed, calm or excited? Compare her hands to those of the archbishop of Canterbury (fig. 11). Again, what details about her hands indicate her character? What would the effect be if her hand were touching the man’s? Imagine yourself in this situation and try to state clearly how you would feel. What does the girl’s body language indicate about her relationship with the man? Are they husband and wife, friends, lovers, recent acquaintances, business partners, employer and employee?

Is the girl elegantly or carelessly dressed, a decent woman or a floozy? Suppose she wore no head covering and had luxuriantly curling, waist-length hair. How would your interpretation of her character shift? What if the white fabric tucked into the top of her bodice were lacy or semi-transparent?

In a series of adjectives or phrases, summarize what you have observed so far concerning this girl’s physical appearance, character, and actions. Again, are there any characteristics that are emphasized by being shown in different ways? Are there any characteristics that seem more fundamental than others—that help explain the others?

Now combine what you have noted about the man and girl separately into a tentative theme that incorporates the most important characteristics of the man and girl, what they are doing, and the nature of their relationship. Write down this first attempt at a theme; later, this will enable you to recall it easily for comparison and revision.

Now consider the items that surround these two figures. What effect does the position of the chairs have? How would your interpretation of the relationship between this man and girl change if the chairs were perfectly aligned with the edges of the table, and the man and girl were sitting stiffly upright in them? What if the chairs had high, elaborately decorated backs that towered over the figures’ heads? What can you guess about the table and chairs: Are they elaborate and expensive, or plain and moderately priced? What does this tell you about the status and possible relationship of the couple? For example, are they wealthy, aristocratic lovers, with nothing to do but dally? Use this information to make your first tentative theme more precise.

Consider the window. Vermeer is famous for the way he depicts light, but this window is not merely an excuse to incorporate sunlight into a painting. In the Last Supper (1495–1498), Leonardo da Vinci for the first time employed the diagonals of linear perspective (a relatively new technical device) to direct the viewer’s attention to a specific part of the painting: Christ’s head. In this painting, the window incorporates almost the only slanted lines in the painting. Like the perspective lines in the Last Supper, they move the eye in a certain direction. Where do the diagonals lead your eye? After you answer that last question, place a ruler or the edge of a piece of paper along the top and bottom of the window to find the “vanishing point” where they meet.

Also think about how the atmosphere of the room and the emphasis of the painting would change if the window were closed, or if it were dark outside, or if we could glimpse a charming landscape outside the window, such as appears in Memling’s Portrait of a Man (fig. 8).

What function does the map on the wall serve? Do the man and the girl pay any attention to it? What if, in its place, there were a large portrait such as Philip IV (fig. 6 )? What if there were only a blank wall? What if there were no map and the top third of the painting were lopped off?

Tweak your tentative theme again, considering what is included in the setting and what is emphasized. Do you think Vermeer is sympathetic to these two figures? Your word choice in the theme should reflect that.

Attributes

What does the light emphasize—where does it fall most strongly? What mood does the light set: bright, dull, cheerful, glum?

What are the dominant colors and what is their effect? How would the mood differ if, instead, the dominant colors were pastel blue, pink, and yellow (like Reni’s Immaculate Conception, fig. 5), neutrals (like the cliffs in St. Francis, fig. 10), or garish purple and orange?

Narrow your focus and consider the colors worn by the man and girl. The man wears vivid red, the girl golden yellow. How would your reading of this pair change if both wore the same colors, or if the girl wore red and the man yellow? (Yes, it is legitimate for this purpose to consider all the associations common in Western civilization, such as “scarlet woman.”) What if both wore cool colors such as blue and green? What is the effect of the combination that is actually used?

Can you make your tentative theme more precise based on the details of light and color that you just observed?

What textures can you discern? How are they distinguished? Look, for example, at the surface of the map in contrast to the stripes on the girl’s sleeve. What does the different treatment suggest about their textures? What does the texture of the clothing tell you about the character of those wearing it? To what do the varying textures draw attention? Imagine the man in threadbare burlap the color of St. Francis’s robe (fig. 10), or the girl in an elaborately bejeweled costume such as Holbein’s Henry VIII wears (fig. 7). What do the textures of the clothing they actually wear suggest about them?

Consider also how sharp the details are. The man’s figure is not depicted with as much detail as the girl’s, and her hands are not depicted as sharply as her face. As we saw in Bellini’s St. Francis, sharpness of detail can be used to direct the viewer’s attention from a less important to a more important section of the painting. Where is your attention being directed in this work?

Can you make your tentative theme more precise based on the attributes you just observed?

Overview

Consider now the composition: the arrangement of objects on the canvas. What is the effect of the way the figures are positioned? What if their positions were switched or the girl’s figure were shifted slightly closer or farther from the man? What if her head were level with his? Does that confirm your earlier thoughts about their relationship? As always, tweak your tentative theme if necessary.

For contrast, consider a nearly contemporary painting: Hooch’s Messenger of Love (fig. 15). What is the relationship between the man and woman there? How do you know? What is emphasized? How is the mood different, and what details indicate that? Tweak your tentative theme for Officer and Laughing Girl based on any additional details you have observed while making this comparison.

Now you should be ready to summarize the painting. What is the subject? What is the artist’s attitude toward it? What will you state as your final theme?

If you and a friend arrive at different themes, do not be dismayed: Rational men can disagree on such matters. At this point, however, if you disagree with someone about the theme of this painting, you should be able to determine what led to the disagreement. You might say, “I see that detail, but disagree with your interpretation,” or “I disagree with your interpretation based on details X, Y and Z, which you did not take into account.” You should not be reduced to saying, “I do not know why, it just feels wrong to me.”