Author’s note: This is the third of three articles for The Objective Standard dealing with the role of ideas in military history. The first two dealt with General William T. Sherman’s march through the South in the American Civil War and the British appeasement of Hitler in the late 1930s. The material in these articles will appear in my forthcoming book, Nothing Less than Victory: Military Offense and the Lessons of History from the Greco-Persian Wars to World War II (Princeton University Press).

This essay is dedicated to General Paul Tibbets (February 23, 1915–November 1, 2007). Colonel Tibbets, commander of the B-29 “Enola Gay,” dropped the first atomic bomb and brought a speedy end to the war.

Between 1889 and 1931, a cancerous tumor took root in the western Pacific Ocean. A nation of seventy million people systematically implanted, into their minds and their culture, an ideology of sacrifice to an Emperor-god. The cancer soon metastasized into a continental war, launched first against Manchuria in 1931, then against China in 1937. In 1941, a coordinated campaign of attacks was launched against the American fleet at Pearl Harbor, as well as the Philippines, Hong Kong, Malaya, Indonesia, and the islands of Guam, Wake, and Midway. By 1942, the cancer had reached the Aleutian Islands, New Guinea, and Burma—and it threatened Australia, India, and the west coast of America. The seemingly invincible Japanese Empire of the Rising Sun controlled one-seventh of the earth’s surface.

By the end of 1945, however, the Japanese had lost it all. Surrounded by an impregnable armada, they lay prostrate before merciless American bombers. The best of their youth had killed themselves in suicide attacks. Their fleet was sunk. More than sixty cities had been firebombed. Two cities had been atom-bombed. They were militarily defeated and psychologically shattered, and they faced the possibility of a famine that could kill millions.

Rather than starvation, however, something entirely different followed. Over the next five years, under stern American guidance, and with zeal as great as that with which they had once armed for battle, the Japanese reformed their nation. They adopted a new constitution, purged their schools of religious and military indoctrination, and abandoned aggressive warfare. Imperial subjects became citizens; “divine” decrees were replaced with rights-respecting laws; rulers became administrators; feudal cartels became corporations; propaganda organs became newspapers; women achieved suffrage; and students learned the principles of self-reliance and self-government. Hiroshima, formerly the headquarters of a fanatical military force, became a world center for nonviolence. Those who had once marched feverishly for war now marched passionately for peace.

What stood between the attacks of 1941 and the rebirth of Japan as a civilized nation were five years of merciless warfare, the incineration by napalm and nuclear attack of nearly 400,000 Japanese civilians, an intransigent demand for unconditional surrender, and six years of postwar military occupation by the United States. The result was the most benevolent turnaround of an entire nation in history.

The victory over Japan remains America’s greatest foreign policy success. Today, we take for granted a peaceful, productive, mutually beneficial relationship with the Japanese people. But this friendship was earned with blood, struggle, and an unrepentant drive to victory. The beneficent occupation of Japan—during which not one American was killed in hostile military action—and the corresponding billions in American aid were entirely post-surrender phenomena. Prior to their surrender, the Japanese could expect nothing but death from the Americans.

If there is one historical event that every American should study, beyond the American Revolution and the Civil War, it is America’s victory over Japan in World War II. Even more than the victory in Europe in the same war—in which we divided Germany with the Soviets—the victory over Japan remains the cardinal example of a complete, unambiguous, and fundamentally unshared American military victory.

The story begins with the cultural background to the Japanese attacks, and the intransigent American drive to victory.

The Cultural Background to the Japanese “Social Pathology”

The rise of a malignant State—or, in contrast, the creation of a government that protects the rights of its people—does not happen in a cultural vacuum. Japanese scholar Eiji Takamae poses the right question: “What social pathology propelled Japan on its course of aggression, leading to defeat and occupation by foreign armies?”1 This pathology—what Tsurumi Kazuko called the “socialization for death”—can be found in virulent sacrificial ideas that the Japanese deliberately inculcated in themselves and their children over the decades preceding the war.2

The historical starting point for Japan’s relations with the modern Western world was in 1853, when American Commodore Matthew Perry sailed four coal-burning ships into Japan and presented a letter from President Millard Fillmore demanding that Japanese ports be opened to U.S. trade. Prior to this gunboat diplomacy, Japan had been closed to outsiders and ruled by military leaders, the shoguns. The shoguns, who were selected by a sort of consensus between noble houses, were much more important than the Japanese emperor. Over the next decade the shoguns signed treaties with the Americans, Russians, French, and British, dramatically expanding Japan’s trade with the West.

The Japanese grappled with foreign influences—especially Western technology and trade—that could conflict with their traditional values. On the one hand, the Japanese wanted Western technology, in order to maintain a position of strength in a world dominated by European powers. Japan soon built a navy, for instance, modeled on Western navies. On the other hand, many Japanese wanted to maintain their traditional values, rituals, and feudal hierarchies, and to prevent the encroachment of Western ideas—especially individualism—that they considered to be incompatible with their culture. Over time they grafted the products of Western culture onto a feudal society that was dominated by traditional warrior ideals, powerful clan ties, coercive economic cartels, a land system akin to sharecropping, and strong family and state power over individuals.

In 1868, in what is known as the Meiji Restoration, dissident samurai warriors drove out the shogun and elevated an Imperial dynasty into preeminence. An imperial decree of 1870 declared the emperor to be a living god, and his throne to be a holy office.3 In the past, the emperor had been powerless, perhaps even a hostage taken by Japan’s military rulers to maintain their power. Now he was refashioned into the nominal head of the nation, the divine anchor for its military rulers, and the living embodiment of the “Yamato race” and the kokutai, the Japanese “national essence.”

In the following decades, Japanese leaders created a mythology in which Japan had been founded by divine action, and the imperial throne occupied from time immemorial, by a direct line of succession from the sun goddess Amaterasu. This national mythology was consciously influenced by Shinto, “a cluster of beliefs and customs of the Japanese people centering on the kami, a term which designates spiritual entities, forces, or qualities that are believed to exist everywhere, in man and in nature.” A good person is supposed to live in harmony with such forces.4 Japanese leaders used Shinto—the dominant religion in Japan—to legitimize the political sovereignty of the emperor, nationalizing Shinto shrines and directing rituals in those shrines to venerate him.5 In time, the Japanese came to think of the emperor as a deity whose throne was of ancient origins and whose wish was to be obeyed.

The emperor, the people, and the land were unified in the cult of the holy kokutai—Japan’s “national essence,” “national polity,” or “fundamental structure.” The kokutai was considered to be the mystical essence of the Nation, akin to the Platonic Form of the Nation, and immutable despite outward changes in Japan’s government. “Kokutai” was a central concept linking the spiritualism of Shinto with a transcendent conception of the Nation. Kokutai Shinto was a system of ideas derived from Shinto mythology, promulgated through Shinto shrines, and adapted to the Japanese nationalistic context.

Enforced by the government, Kokutai Shinto developed into the national cult of “State Shinto.” State Shinto leveraged the context of religious mysticism given it by traditional Shinto in order to mandate Emperor-worship, to demand obedience to his word as an unquestioned absolute, and to inculcate the Japanese with a willingness to sacrifice for the sake of both the emperor and the kokutai.6

The Meiji Constitution of 1889 codified this mythology into law. It defined the emperor as the highest authority over Japan: “The Empire of Japan shall be reigned over and governed by a line of Emperors unbroken for ages eternal”; “The Imperial Throne shall be succeeded by Imperial male descendants, according to the provisions of the Imperial House Law”; “The Emperor is sacred and inviolable.” The connection to the military was central: “The Emperor has the supreme command of the Army and Navy”; “The Emperor declares war, makes peace, and concludes treaties”; “Japanese subjects are amenable to service in the Army or Navy, according to the provisions of law.”7

The Meiji Constitution had a specific source. In the 1870s and 1880s, the Japanese debated what kind of constitution they wanted, and, as part of the process, sent representatives overseas to gather information about Western constitutions. They ultimately rejected the English and American options—along with notions of individual rights and popular consent—in favor of Prussian-based authoritarianism. The Meiji Constitution brought German nationalism to Japan and merged it into the existing feudal and patriarchal social organization, with the blessings of Shinto. The Germanic conception of the political State—accepted by the Japanese—was of a Nation that was headed by an Emperor to whom all must subordinate their lives.8

There were no individual rights in such a conception and no limits as to the overall power of government. There were no citizens in Japan, only subjects of the emperor whose minds and bodies were subordinated to his embodiment of the kokutai. The Japanese people were told that “the way of the subject is to be loyal to the Emperor in disregard of self, thereby supporting the Imperial throne coextensive with the Heavens and with the Earth.”9 The Imperial “wish” became law, disseminated through rescripts (written statements or decrees) and written into each subject’s mind as a moral absolute—recited, memorized, believed, and accepted as a divine commandment.

It would be a mistake to think of the emperor as the direct ruler of the nation, however, for he was conceived as a god, and gods do not often interact with men. The emperor reigned, he did not rule, and he did so in aloof isolation from his subjects. The Meiji Constitution established a legislature, the Diet, which served at the behest of the emperor. It also placed the authority of the emperor behind a warrior class, which grew in political power over decades—and to which the emperor owed his position. The ancient relationship between the warriors and the emperor was reconstituted. The emperor’s wish became the means to legitimize the decisions of a military clique—who saw themselves as the guardians of the Nation.

The key to the power that the emperor and the military held over Japanese culture was the system of government schools. In 1890, the emperor issued one of the most important documents in modern Japanese history, the Imperial Rescript on Education. The purpose of the rescript was to “counteract . . . interest on the part of the masses in things Western and a corresponding neglect of Japan’s traditional culture.”10 This decree bound every child to a system of education that focused on worshipful obedience to the Emperor, sacrifice to the Nation, warrior virtues, and military training. School principals would recite the rescript before their students in a rigid ritual, and mispronunciation of a single word could end in suicide.11

Every Japanese child went through this indoctrination. From the moment he could speak, veneration of the imperial throne and duty to the state were drummed into him. To learn grammar he wrote out, in longhand, lesson books extolling service to the emperor. He learned kodo, the imperial way, and was told that morality was on, his obligation to his emperor and his parents. It was drummed into him that the emperor was the embodiment of the kokutai, and that the Nation was greater than any of the individuals who comprised it. He learned that spreading the emperor’s dominion was honor, and that defeat was dishonor, which was worse than death. He memorized the emperor’s words—especially the Rescript on Education—and recited its tenets before an image of the emperor. He looked to the emperor as the source and standard for moral judgments.12 He dreamed of fighting for the emperor.

The educational focal point for the students was the imperial portraits. In a position of worship, and with an attitude of penitent obedience, children faced the portraits, which were ceremonially uncovered while they recited the Educational Rescript. The emperor’s image took on the status of a religious icon in their minds. Honor guards watched over the portraits, and teachers died trying to save them from fires. After the sinking of the battleship Yamato in 1945, a surviving sailor reported that a comrade had locked himself and the imperial portrait in his cabin as the ship went down, in order to protect the emperor’s image.13

As a result, fanatical military ideals resonated with people on the street—educated people—trained from their earliest days in “blind submission to the Throne and the Imperial state.”14 Historian John Dower relates how an imperial subject, upon hearing that the emperor was to speak on the radio for the first time, knelt and repeated the words of her youth as they rose in her mind: “Should any emergency arise, offer yourselves courageously to the State.”15 This was the moral law she had deeply absorbed. She did not want to die—but she and millions of others were ready to do so if the emperor so wished.

The response of individual Japanese to this “socialization for death” took many forms, ranging from militant fanaticism to weary resignation, from undying imperial loyalty to a willingness to ridicule the emperor’s defeat or even replace him after the war. But, although not every Japanese civilian was a mindless fanatic, none could fully escape the ideas drilled into him from childhood under the state system of education. Those who rose to control the political system, and to set the basic direction of the nation, were the most extreme—that is, the most principled—of those fanatics. Any doubts people might have had were drowned in the tsunami of their indoctrination and the cultural environment it created. If all else failed, and someone forgot his position as a subject by questioning either the emperor or the actions of the military, the state security forces—charged with maintaining ideological conformity—would take direct action.

With this political, social, and educational system in place, and motivated to attain a place of dominance in Asia, the Japanese set out to conquer an empire, “as befitted their destiny as a superior race.”16

In 1894–1895, a war on mainland Asia left Japan with control over parts of China. But this was followed by a humiliating retreat from Liaotung Peninsula in Manchuria, a retreat that was not forced by the military success of Japan’s foes, but that was agreed to under diplomatic pressure from European nations. Many Japanese were highly motivated to regain what they believed had been unjustly taken from them in 1895; their victory in the 1904–1905 Russo-Japanese War allowed them to do so. A negotiated peace, the so-called Treaty of Portsmouth, brokered by U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt (for which he won the Nobel Prize), somewhat affirmed the Japanese position. But it also required the Japanese to give up territorial claims in Asia that many thought they should keep, including Manchuria. Once again, the peace did not satisfy the desire among the Japanese to control the Asian mainland—and to oppose the spread of “things Western” in Asia.

During World War I, Japan supported England, the United States, and France, by attacking German colonies in the Far East, and became a player on the international scene when given a victor’s position at the Paris Peace Conference after the war. But many European leaders—who were interested in developing their Asian colonies—began to see Japan as a competitor who would cut into their share of the “Chinese Melon.”17 A motivated group of Japanese recognized that increased European influences due to colonization in the Far East would endanger their way of life, and they renewed their commitment to take control of Asia.

During the 1920s and 1930s, the most radical elements of the military leadership solidified their hold over Japanese society. They had fashioned the emperor into a source of legitimacy for their decisions, and made him a point of focus for the imperial subjects. But military officers did not all agree on the best way to serve the emperor. Factions formed within the army over which policies would best protect the holy Japanese “national essence” and preserve its traditional values. Some officers favored an outright invasion of Asia, whereas others favored slower or more indirect action. Everyone agreed about the ultimate aims, however; they disagreed only about the best methods by which to achieve those aims.

The invasion of Manchuria in 1931 by the Kwantang army—acting without orders from the government in Tokyo—broke the treaty that had ended the Russo-Japanese War in 1905.18 This ominous action demonstrated the ability of the army to act independent of political control, should they decide that they better served the Nation than did their government. Political leaders were unable to demand the withdrawal of the army, precisely because its commanders purported to act in service to the emperor, and in the interest of the holy kokutai.

In October 1931, a conspiracy of officers rose against the government in Tokyo and in support of the army on Manchuria. The minister of war in Tokyo sent a radio communication to the army, excerpted here:

1. The Kwantang Army is to refrain from any new project such as becoming independent from the Imperial army and seizing control of Manchuria and Mongolia.

2. The general situation is developing according to the intentions of the army, so you may be completely reassured.19

The commander of the Kwantang army replied that he had acted as he had “for the country.” Because the different factions agreed on the aims—the aggrandizement of the nation and the emperor—and because so many soldiers sympathized with the rebels, there was no effective opposition to the unauthorized attack. Critics collapsed into awe and respect when they recognized that the army acted as it had in order to achieve the fundamental aims that all agreed were proper.

Some military officers opposed aggression as a means to aggrandize the state. They offered the last serious challenge to a policy of war. But they remained sympathetic to the overall aims of their more radical comrades—and were thus unable to end the aggression in Manchuria. In February 1936, a rebellion by these anti-aggression officers in Tokyo led army leaders to issue a statement, in the name of the emperor, that included: “Your action has been recognized as motivated by your sincere feelings to seek manifestation of the national essence (kokutai).” The statement continued: “The present state of manifestation of kokutai is such that we feel unbearably awed.”20 The leaders were “awed” before the nationalistic feelings of the rebels—just as the rebels were awed before the feelings of those officers advocating aggressive war in Manchuria. Everybody was in awe of anybody who shared his feelings for the “national essence.”

As always, when conflicts arise between people ascribing to the same basic premises, those who uphold those premises more consistently win, while those who compromise and take a more “moderate” position lose. The end result in Japan in the 1930s was the triumph of the radicals for violent expansion. Those who advocated the naked essence of their indoctrination—military conquest—rose to control the government. They took the country to war.

In 1937, Japan launched its war against China, this time with the full approval of the Tokyo government. Military force was to be used to rid Asia of the Western influences that many Japanese saw as threats to their traditional values and to the expanding rule of the emperor. By this point plans for a wider war—which required a population ready to sacrifice and die at the behest of the leadership—were underway.

At each step, the supremacy of the emperor, and the duties of his subjects to him, were reinforced through propaganda and imperial decrees. In March 1937, the Education Ministry released the “Cardinal Principles of the National Polity” (kokutai no hongi), which reaffirmed the central position of the 1890 Rescript on Education in Japanese life. The emperor was now referred to as a “deity incarnate.” In July 1941, the government published the Shimmin no Michi (“The Way of the Subject”), which reaffirmed the national mythology of the emperor as having descended from the sun goddess Amaterasu, and defined the ruling “national polity” (kokutai) as a “theocracy” in which “the way of the subject is to be loyal to the Emperor in disregard of self, thereby supporting the Imperial Throne coextensively with the Heavens and the Earth.” This handbook for subject-hood denounced “individualism, liberalism, utilitarianism, and imperialism” as threats to the Japanese virtues of filial piety and of sacrifice to the national polity and the emperor.21

As he went forth to serve His Majesty the Emperor, every Japanese soldier carried his duties in the form of the Senjinkun or Field Service Code, a guide for fighting the emperor’s war:

The battlefield is where the Imperial Army, acting under the Imperial command, displays its true character, conquering whenever it attacks, winning whenever it engages in combat, in order to spread the Imperial Way far and wide so that the enemy may look up in awe to the august virtues of His Majesty.22

That true character was revealed on December 13, 1937, when the emperor’s holy warriors entered Nanking, China. The “Rape of Nanking” was a rampage that killed some 300,000 Chinese—nearly double the deaths caused by the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki combined. Thousands of women were gang-raped and forced into military prostitution. Thousands of Chinese civilians were herded and machine-gunned, used for bayonet practice, buried alive, doused with gasoline and burned, or decapitated with swords before smiling Japanese troops, their heads then publicly displayed. The Japanese media covered the killing contests; the Japan Advertiser ran pictures of two officers who competed to see who would be the first to kill one hundred men with a sword.23

In sum, World War II in the Pacific was launched by a nation whose highest ideals were violently hostile to human life. Japan’s religious-political philosophy held the emperor as a god, subordinated the individual to the state, elevated mythology and ritual over rational thought, adopted aggression as its basic foreign policy, and justified the rape and torture of the “inferior” people it conquered. This morality of death was leading Japan to the brink of national suicide.

(One of the reasons often cited by apologists for the growing confrontation between Japan and the United States was the American–British–Dutch oil embargo against Japan, begun in July 1941. Although many Japanese regarded the embargo as an act of war, the embargo did not cause the Japanese attack on Manchuria in 1931 or the Rape of Nanking in 1937. The huge Japanese navy certainly needed oil by the thousands of tons, but the navy itself and Japan’s military conquests were the consequences of the ideas that led the Japanese to wage war. When these ideas were abandoned after their defeat in 1945, the Japanese would acquire all the oil they needed—through production and trade.)

The December 7, 1941 attack on the American fleet at Pearl Harbor was only one prong of a coordinated campaign in Asia and across the Pacific Ocean. U.S. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt detailed the campaign the very next day in his rhetorically powerful request for a declaration of war:

The attack yesterday on the Hawaiian Islands has caused severe damage to American naval and military forces. . . .

Yesterday the Japanese Government also launched an attack against Malaya. Last night Japanese forces attacked Hong Kong. Last night Japanese forces attacked Guam. Last night Japanese forces attacked the Philippine Islands. Last night the Japanese attacked Wake Island. And this morning the Japanese attacked Midway Island.24

On that same Monday, December 8, the Japanese emperor issued an imperial rescript on the war—another “divine wish” designed to reemphasize the position of each Japanese as an imperial subject. The emperor again demanded their subservience, which the Empire of Japan would need in order to sustain its planned aggression. The population bowed their heads in awe and submission, prepared to sacrifice and die.

By mid-1942, the Japanese controlled an area of the Pacific and Asia that was six times larger than the United States. The Americans had retreated from the Philippines, and General Douglas MacArthur was ordered to reestablish his base in Australia. Thousands of Americans, including American General Jonathan Wainwright, were herded like animals in the Bataan Death March. Brave Filipinos were subjected to a long nightmare of brutal occupation and jungle warfare. Attacks on Australia and India were looming. The Japanese home islands were far beyond the capacity of American forces to reach effectively.

To roll back and end Japan’s drive for empire would require much more than a military defense. To permanently end its bloodlust, serious changes would have to be made inside Japan. Before such changes could be made, however, Japan would have to be thoroughly defeated militarily.

The American Drive to Victory

At the start of World War II, Americans were woefully unprepared for war—because they did not desire war. In the wake of World War I, they wanted one thing: “normalcy,” to pursue prosperity through private enterprise. “The business of America is business” summed up this attitude. Whether or not Roosevelt was eager to shift the American public’s focus from his failed New Deal to the war with Japan, it was the Japanese who, in fact, started the war. The complex sneak attack on the American fleet at Pearl Harbor had been planned well in advance. Roosevelt recognized the nature of the attack in his request for a declaration of war:

Yesterday, December 7, 1941—a date which will live in infamy—the United States of America was suddenly and deliberately attacked by naval and air forces of the Empire of Japan. . . .

It will be recorded that the distance of Hawaii from Japan makes it obvious that the attack was deliberately planned many days or even weeks ago. During the intervening time the Japanese Government has deliberately sought to deceive the United States by false statements and expressions of hope for continued peace.

The attack yesterday on the Hawaiian Islands has caused severe damage to American naval and military forces. I regret to tell you that very many American lives have been lost. In addition, American ships have been reported torpedoed on the high seas between San Francisco and Honolulu. . . .

As Commander-in-Chief of the Army and Navy I have directed that all measures be taken for our defense.

Always will we remember the character of the onslaught against us. No matter how long it may take us to overcome this premeditated invasion, the American people, in their righteous might, will win through to absolute victory.

I believe that I interpret the will of the Congress and of the people when I assert that we will not only defend ourselves to the uttermost but will make it very certain that this form of treachery shall never again endanger us.

Hostilities exist. There is no blinking at the fact that our people, our territory and our interests are in grave danger.

With confidence in our armed forces, with the unbounded determination of our people, we will gain the inevitable triumph. So help us God.

I ask that the Congress declare that since the unprovoked and dastardly attack by Japan on Sunday, December 7, 1941, a state of war has existed between the United States and the Japanese Empire.25

The president’s statement was first and foremost an accurate identification of the reality of the situation. Since the attack, he said, “a state of war has existed between the United States and the Japanese Empire.” Roosevelt did not call the war into being. He did not ask Congress to start a war, but rather to formally recognize that war had begun. Congress issued a Declaration of War within the hour. The Japanese had committed aggression, willfully and with forethought, and Roosevelt correctly identified this action as the initiation of war. “Hostilities exist,” and Americans would not blink at the danger; rather, they would be energized by the knowledge that they were in the right.

Roosevelt’s words were directed outward, against the threat, not inward at American losses. He established a goal-directed posture with respect to Japan. He did not wallow in the details of the carnage in Hawaii, nor call the American people virtuous for having suffered. He did not harp on the need to take care of our wounded, nor dwell on the patriotism of those who gave blood (both of which were assumed). The entirety of his report about the damage was contained in three short sentences. Roosevelt wanted Americans to focus their efforts toward eliminating the threat, toward making “very certain that this form of treachery shall never again endanger us.” And he wanted Japan to know that we had no intention of backing down from this goal.

The goal to be achieved was “absolute victory,” or “the inevitable triumph.” Its achievement required four key steps:

- identify the enemy;

- decide to defeat him;

- define victory;

- and commit, over time, to achieve that victory.

Roosevelt’s speech accomplished the first two of these vital steps—the cognitive act of identifying the enemy and the decision to act on that identification. The remaining steps were more complex.

Note that “achieving victory” would have been insufficient as a goal, for it would have failed to specify the nature of “victory.” To achieve victory, one must first know what victory is. Does victory consist in pushing the enemy back to his own soil? Getting him to attend peace talks? Forcing him to stand down for the moment? Holding democratic elections in his country?

The question was: What specifically would constitute victory for America? The answer was: the total and permanent destruction of Japan’s will and capacity to fight. The war had begun with a conscious decision by the Japanese to attack—following years of energetic work to build a force capable of dominating the Pacific. Ending this threat would require a conscious decision by the Japanese—including their leadership, army, and population at large—to renounce aggression totally and permanently. The war was made possible by Japan’s aggression-oriented ideology and its military machinery. Ending this threat would require Japan’s repudiation of that ideology along with its thorough and permanent disarmament. Victory would mean the permanent reversal of the Japanese decision and commitment to fight, demonstrated in action. The full meaning of these (and other) requirements of American victory was integrated into three words: Japan’s unconditional surrender.

The decision by the United States to achieve unconditional surrender would have to be reiterated and renewed over years of struggle and tens of thousands of casualties. Roosevelt held to his commitment for the remaining three years of his life, refusing all suggestions to dilute the goal or negotiate for a partial victory. “Always will we remember the character of the onslaught against us” was his commitment. Despite his many attacks on individual rights in America—such as his coercive wealth redistribution programs—when it came to war with Germany and Japan, he did the one thing required to end the war permanently: He established victory as the goal, he defined it, and he remained committed to it. And following his lead, America set forth to achieve this victory.

Roosevelt reaffirmed this commitment in January 1943 at the Casablanca Conference with British Prime Minister Winston Churchill:

The President and the Prime Minister, after a complete survey of the world situation, are more than ever determined that peace can come to the world only by a total elimination of German and Japanese war power. This involves the simple formula of placing the objective of this war in terms of an unconditional surrender by Germany, Italy and Japan. Unconditional surrender means not the destruction of the German populace, nor of the Italian and Japanese populace, but does mean the destruction of a philosophy in Germany, Italy and Japan which is based on the conquest and subjugation of other peoples.26

This so-called “simple formula” was the product of true leadership, a way of focusing the American people on a clear goal, one that would remove the underlying causes of the war. While still at Casablanca, Roosevelt stated, in front of some fifty reporters:

I think we have all had it in our hearts and heads before, but I don’t think that it has ever been put down on paper by the Prime Minister and myself, and that is the determination that peace can come to the world only by the total elimination of German, Japanese and Italian war power.

Although unconditional surrender had been discussed many times, it was at Casablanca that the goal was made public. Roosevelt continued: “The elimination of German, Japanese and Italian war power means the unconditional surrender of Germany, Italy and Japan.”27

The achievement of victory through the unconditional surrender of the enemy became the unwavering goal of America. At the First Quebec Conference, in August 1943, Roosevelt and Churchill set a timetable for the surrender of Japan: It was to occur within one year of the surrender of Germany. The goal was to get the job done before the American public wearied of the war and could be influenced to back down from their commitment to eliminate the threats they faced.

The demand for unconditional surrender was restated on November 27, 1943, in Cairo, where Roosevelt, Churchill, and Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek of China issued a statement that included the following:

The Three Great Allies [the United States, Britain, and China] are fighting this war to restrain and punish the aggression of Japan. They covet no gain for themselves and have no thought of territorial expansion.

It is their purpose that Japan shall be stripped of all the islands in the Pacific which she has seized or occupied since the beginning of the First World War in 1914, and that all the territories Japan has stolen from the Chinese, such as Manchuria, Formosa, and the Pescadores, shall be restored to the Republic of China. Japan will also be expelled from all other territories which she has taken by violence and greed. . . .

With these objectives in view the three Allies, in harmony with those of the United Nations at war with Japan, will continue to persevere in the serious and prolonged operations necessary to procure the unconditional surrender of Japan.

We will return later to the full meaning and function of “unconditional surrender.” Suffice it here to note that Roosevelt, speaking to Secretary of War Stimson in reference to Germany, said, “The German people as a whole must have it driven into them that the whole nation had been engaged in an unlawful conspiracy.” He had also said, at an earlier press conference, that “practically all Germans deny the fact that they surrendered during the last war, but this time they are going to know it. And so are the Japs.”28 Roosevelt, as an assistant secretary of the navy under Woodrow Wilson during the First World War, had seen the destructive consequences of the failure to defeat Germany in 1918. He was determined not to repeat this error.

“Victory,” and the drive to unconditional surrender, became an integrating idea for millions of people. Americans planted Victory Gardens, and flashed the Victory Sign. The Office of War Information, a propaganda arm of the U.S. government, set out to keep the idea of unconditional surrender alive. A June 1945 pamphlet stated: “Only Unconditional Surrender can lead to the smashing of militaristic hopes and ambitions” in Japan.29 According to a survey at the time, Americans thought by a margin of nine to one that Japan must be “completely beaten.” By the time Harry S Truman took office in April 1945, he might have been impeached had he tried to deviate from this formula.

The Japanese Decision to Surrender

The months after Pearl Harbor were some of the darkest moments in American history. The destruction of the U.S. Air Force at Manila, General Douglas MacArthur’s retreat from the Philippines, and the Bataan Death March remain some of the saddest. At that time, the Americans did not have the capacity to end the Japanese onslaught. Even two years after Pearl Harbor, the Americans had advanced only some two hundred miles up from the south. One journalist commented that, at that rate, they would get to Tokyo by 1960.30

But, early difficulties aside, the Americans were on their way to Tokyo—of that everyone was certain. Americans were driving toward victory over tyranny—a far different goal than expanding the reign of His Majesty the Emperor. While the Japanese were bound to rituals and seeking death for the emperor, the Americans were focused on winning the war and returning home alive. For the American soldiers, who valued their lives, defeat in battle one day meant they could still fight for their lives the next; for many Japanese soldiers, a defeat in battle ended in ritual suicide. Throughout the war, American forces grew in experience while the best of the Japanese—especially their pilots—died at their own hands. And, given their rational commitment to material prosperity through private property, the Americans greatly outproduced the Japanese in terms of weaponry. The Japanese economic cartels could not compete with American free enterprise—and Japan’s suicidal culture could not compete with America’s positive sense of life.

By mid-1944, the war had turned unalterably against Japan. In July 1944, the Americans took Saipan and the Marianas. The government of Tōjō Hidecki fell, and Japan’s management of the war was reorganized under the six-member Supreme Council for the Direction of the War, or the “Big Six.”

The Big Six could approach the emperor for his sanction only after they had reached unanimous agreement. Without exception he then approved their decision. The military controlled three of the six positions, and they could deadlock the council or force the removal of the prime minister—the nominal head of the Big Six—at any time. In lieu of a unanimous vote, a decision would not be issued—and absent a specific decision to end the war, the military continued fighting. The effects of the overwhelming American onslaught on Japan in the last months of the war can be understood only with reference to the ideas that motivated the Japanese leadership—and the consequent paralysis in Japanese political decision making that developed prior to the dropping of the atom bombs.

In the last months of 1944, MacArthur swept up from Australia and around Japanese troops on New Guinea, and returned to the Philippines. In February and March 1945, Admiral Chester Nimitz moved his navy toward Japan from the east and took the island of Iwo Jima in some of the most brutal fighting of the war. These movements placed Japanese cities within the reach of American bombers. On April 4, 1945, the U.S. commands were unified into the U.S. Army Forces in the Pacific (USAFPAC), and MacArthur was placed in overall command.

In early 1945, the Americans stepped up their bombing of Japanese cities. But high-altitude bombing missions remained long, dangerous, and ineffective; the jet stream blew bombs off course and made it impossible to destroy industrial targets with precision from six miles high. A study of British night bombing in Europe showed that only 20 percent of dropped bombs landed within five miles of their targets. Unable to destroy Japanese industries, Air Force commander General Haywood Hansell Jr. was replaced by General Curtis LeMay. On the night of March 9–10, 1945, LeMay took a huge gamble, which many of his officers opposed as excessively risky for American forces. High-altitude bombers, designed to fly at more than 30,000 feet, flew over Tokyo at 5,000 feet, overloaded with incendiary bombs that would be dropped directly on population centers closely packed with balsa wood homes. After pacing all night, LeMay learned that his mission had been a success: A horrendous firestorm aided by 25-knot winds blowing in from the west had killed more than 80,000 Japanese.

By summer, bombing missions over Japan were the safest combat duty in the Pacific theater. Until this point, American commanders agreed that Japan could be defeated only with a land invasion. But LeMay was beginning to doubt conventional wisdom; in April he wrote that “the destruction of Japan’s ability to wage war is within the capability of this command.”31 Perhaps it would not be necessary to spill rivers of American blood in a land invasion.

The Japanese had no defense against the American bombing. But though they were, in fact, defeated, their warrior ideals led them to evade that fact, and they were still able to kill Americans—as they had at Iwo Jima and Okinawa—which they thought was the route to a negotiated settlement. Japanese leaders recognized American material superiority, but many remained convinced that the Americans’ will to fight would collapse—if the Japanese people were willing to make the final assault on the home islands deadly enough. Many Japanese officers were obsessed with the idea of a “final battle” against an American invasion, a denouement that would allow them to preserve the Japanese “national essence.”

The result was the basic Japanese strategy of 1945. Issued in January 1945, Ketsu-Go—the “Decisive Defensive Plan for the Homeland”—was a plan for a final battle on the Japanese homeland. When Okinawa fell in June, the civilian and military authorities issued the “Fundamental Policy for the Conduct of the War,” backed by an imperial war rescript, which instructed the nation to fight to the death with no surrender. When the anticipated American invasion began, the Japanese hoped to force a negotiated settlement by causing unacceptable casualties for the Americans. All that was needed was for millions of Japanese civilians to be willing to throw their bodies at the Americans in a last charge to protect the Emperor and the Nation.32

The banzai charge was of ancient origin. Americans had seen it at Saipan, where the last remnants of a defeated Japanese defensive force drank a final toast, armed themselves with bayonets, pistols, and sharpened sticks, and charged American armored positions. They did not expect to defeat the Americans, but to die and preserve their “honor.” To motivate Japanese civilians to die for the emperor, government propaganda praised soldiers and civilians who died at Saipan as heroes. A national banzai charge would be a suicidal “decisive engagement” against an American invasion of Japan—the final spasm of a suicidal ideology. “One hundred million deaths rather than surrender” was a popular saying, especially in the military.33

For many Japanese leaders, an American invasion—and the deaths of millions of Japanese civilians—were an energizing hope. Kamikaze pilots related how “the dream and hope always persisted. . . . [u]sually unwarranted as they were.”34 The hope was pure, morbid fantasy—the culmination of the national mythology that they had been injecting into themselves for two generations. For Japan, “victory” had become nothing more than the sight of thousands of dead Americans, piled on top of millions of dead Japanese.

No issue better illustrates the difference between the Japanese and the Americans during World War II than their attitudes toward an American invasion of the Japanese home islands. The Americans dreaded the idea of such an invasion, and would have done anything to win without it. Many in the Japanese military leadership longed for such carnage—as it was their final hope of forcing the Americans to accept Japan’s existence as an empire. Americans remembered that battles such as Saipan and Okinawa had required them to kill more than 97 percent of the Japanese defenders. Japanese leaders saw this willingness to die as their great strength—especially when multiplied by millions of Japanese civilians. Trapped between their ideals—which demanded no surrender—and the American power converging on them, a suicidal final charge was their only option.

Army Minister Anami Korechika embodied the inability of the Japanese leadership to reconcile its military ideals with the stark reality of defeat. A staunch supporter of traditional Bushido warrior ideals, skilled in archery and swordsmanship, Anami also recognized that intransigence by the Japanese in the face of an American land invasion would lead to mass death. He tried to control the most fanatical officers in the Ministry of War—but he also sympathized with them deeply. He believed that the loss of the imperial line would mean the loss of Japan’s very identity as a nation—the kokutai—which was worth more than the lives of all of the emperor’s subjects. To avoid this, he was willing to commit any evasion, to embrace any apparition of hope, and to sacrifice any number of Japanese civilians. This was true nationalism—the Nation “transcended” any individual lives—and the Emperor was its divine embodiment. In his mind, if the Japanese people had the will to fight to the death, the Nation might be saved.

The Japanese leaders were not the only ones in denial of their failure. The Japanese population was also disconnected from reality by an endless stream of propaganda that consistently misrepresented the military position of the Japanese and exhorted them to sacrifice. After the surrender in 1945, Kodama Yoshio, a political figure in prison awaiting trial as a war criminal, wrote his book I Was Defeated as a statement for his trial:

Although the nation was resigned to the fact that the decisive battle on the Japanese home islands could not be avoided . . . they still thought that the Combined Fleet of the Japanese Navy was undamaged and expected that a deadly blow would be inflicted sometime either by the Japanese Navy or the landbased Kamikaze suicide planes upon the enemy’s task forces. Neither did the nation know that the Combined Fleet had already been destroyed and neither could they imagine the pitiful picture of rickety Japanese training planes loaded with bombs headed unwaveringly towards an imposing array of enemy dreadnaughts [big-gun battleships].35

A “Die for the Emperor” propaganda campaign on Japan took advantage of the indoctrination to which the Japanese had been exposed since birth. Motivated by their indoctrination, and misled by the propaganda, Japanese forces on the southern island of Kyushu swelled to 900,000. They dug into caves and prepared to fight from every hole and rock in the mountains. Without a whimper of popular protest, Hiroshima was made the southern command center for the Japanese Second Army Group, which would coordinate the suicidal “decisive operation” to kill Americans. The government established Area Special Policing Units, charged with “a seamless fusion of the military, the government, and the people.” Officials prepared to call one million civilians in Kyushu alone into active service. They suspended all schooling beyond the sixth grade for one year, so that middle-school- and high-school-aged children could assist in the decisive battle against the Americans.36 Women lined up with sharpened sticks and prepared to drive the Americans back. There were no marches for peace, no calls in the press for the leadership to give up its obsession with military glory, no vigils for Americans killed at Bataan, no questioning of the emperor’s rescripts. Instead, the Japanese continued to work diligently at the Mitsubishi Steel and Arms Works in Nagasaki to churn out materials for weapons.

Surrender or death were the only choices open to the Japanese. These pitiless alternatives were made explicit by American and British leaders, who offered the Japanese one last chance to accept unconditional surrender and end the war. In July 1945, Truman, Churchill, and Soviet dictator Josef Stalin met at Potsdam, an area in Germany south of Berlin and inside the Soviet zone of occupation.* The statement of their commitment to unconditional surrender was the Potsdam Declaration of July 26, 1945. Since Russia had not yet entered the Pacific war, the leaders of only three nations—the United States, Great Britain, and China—signed the statement. Although international approval of the allies was high, there was no broad international coalition to sign it, and the Japanese continued to maintain embassies in many countries—including Russia.

The thirteen-point Potsdam ultimatum, the “Proclamation Defining Terms for Japanese Surrender,” included the following:

The result of the futile and senseless German resistance to the might of the aroused free peoples of the world stands forth in awful clarity as an example to the people of Japan. The might that now converges on Japan is immeasurably greater than that which, when applied to the resisting Nazis, necessarily laid waste to the lands, the industry and the method of life of the whole German people. The full application of our military power, backed by our resolve, will mean the inevitable and complete destruction of the Japanese armed forces and just as inevitably the utter devastation of the Japanese homeland.

The time has come for Japan to decide whether she will continue to be controlled by those self-willed militaristic advisers whose unintelligent calculations have brought the Empire of Japan to the threshold of annihilation, or whether she will follow the path of reason.

Following are our terms. We will not deviate from them. There are no alternatives. We shall brook no delay. . . .

We do not intend that the Japanese shall be enslaved as a race or destroyed as a nation, but stern justice shall be meted out to all war criminals, including those who have visited cruelties upon our prisoners. . . .

We call upon the government of Japan to proclaim now the unconditional surrender of all Japanese armed forces, and to provide proper and adequate assurances of their good faith in such action. The alternative for Japan is prompt and utter destruction.37

The ultimatum accomplished several things. It accurately represented the facts of Japan’s situation, and it compared that situation to the awful precedent set in Germany. It made the basic American demand clear for both the Japanese and the world. It gave Japanese leaders a chance to save the lives of their own people by giving in to the armada facing them. It stated that the intention of the victors was not to destroy the population of Japan, but to bring justice to war criminals. And, as an ultimatum, it eliminated any possibility of negotiations between the Americans and the Japanese.

When the Japanese received the ultimatum, the Japanese leadership was unable to agree on a formal reply. With the (English-language) newspapers indicating that the leadership would “ignore” the ultimatum, the “prompt and utter destruction” that the President had promised would soon follow. (“Ignore” was an inadequate translation of the Japanese word mokusatsu, which defies translation without context. It could mean “consider” it, or “table” it, or “take it under advisement”—it was not a rejection. Mistranslation aside, the Japanese leadership was unable to make a coherent statement on the ultimatum, which was effectively the same as rejecting it. They did not correct the mistranslation or even state that they were formulating a reply.)

During the two weeks that followed Potsdam, the Japanese Big Six engaged in a series of meetings. Their dominant concern was to protect the Japanese “national essence” by preserving the imperial system and the position of the military. Many Japanese leaders still thought that they could cause enough casualties during an American invasion that the Americans would accept an agreement leaving Japan under Imperial control. It was a measure of the Japanese mind-set—and of the need for them to see a demonstration of American will—that many Japanese read the Potsdam ultimatum as a weakening of American resolve.38 They reasoned that if the Americans truly had the will to win they would not ask for their defeated enemy’s agreement in the matter.

The evasions of the Japanese leadership became more fervent as the crisis became more inescapable. Japanese leaders remained trapped between the irrational demand of their ideals to fight to the death and the glaring fact of their defeat. The Big Six were politically deadlocked between a hard-line faction, represented by Army Minister Anami, who would agree to no terms with the Americans, and a faction who wanted to petition for peace, albeit with conditions to preserve the Imperial household. Without unanimous agreement, the Big Six could not issue a decision. Absent a specific decision to surrender, frantic preparations for the final battle continued. Meanwhile, the Japanese emperor ordered the preservation of the symbolic imperial regalia—a mirror, a jewel, and a sword. His priority in the face of destruction was on preserving the physical symbols of the Imperial household, not on preventing the deaths of his subjects.39

Japanese leaders continued to grasp at any straw, however irrational, to find hope of victory. Some were so deluded as to think that the Russians—who had taken control of Eastern Europe and were assembling a massive army to sweep across Asia—would actually enter the war on Japan’s behalf. Foreign Minister Tōgō Shigenori (not to be confused with former prime minister Tōjō Hidecki) instructed Sato Neotake, the ambassador to Russia, to induce the Russians to adopt a vague, undefined “favorable attitude” toward Japan.40 One section of Sato’s answer to Tōgō’s ridiculous assignment summed up the issue concisely: “If the Japanese Empire is really faced with the necessity of terminating the war, we must first of all make up our minds to terminate the war. Unless we make up our own minds, there is absolutely no point in sounding to the views of the Soviet Government.”41 As Sato realized, the Japanese leaders were utterly incoherent in their thinking and unable to communicate intelligible instructions to their representatives.

There were still no voices in Japan arguing openly for peace, no prominent or effective “Peace Party.” Critics of American policy have charged that the American demand for unconditional surrender made it impossible for such a faction to gain influence. Had the Americans been willing to compromise a bit, they have argued, the Japanese might have come to terms, and many lives might have been spared. But the evidence does not support this view. In January 1942, when Tōgō stated before the Japanese Diet that it was necessary to work for peace, his remarks raised a storm of protest and were stricken from the minutes.42 Prime Minister Tōjō Hidecki had faced opposition over his aggressive policies, but the fall of his government in July 1944 was not enough to allow open opposition to the war to coalesce. The “Yoshida Anti-War Group” was a loose-knit group of people who wanted a negotiated end of the war—in order to preserve the traditional aristocratic state. But it remained underground, and “in practical terms the results of its activities were negligible.”43

In early 1945, Okada Keisuke—one of the jūshin, or former prime ministers—advised the emperor to consider ending the war. But he urged the use of kamikaze attacks to achieve the victory needed to bargain for favorable terms.44 Only former prime minister Prince Konoye Fumimaro spoke out in favor of peace, in a “Memorial to the Throne” that urged the emperor to end the war. His argument was that the war had unleashed radical social forces that threatened to incite a socialist revolution in Japan. “Regrettably, I think that defeat is inevitable. . . . More than defeat itself, what we must be concerned about from the standpoint of preserving the kokutai is the communist revolution which may accompany defeat.”45 The Americans, he thought, were far less of a threat to the “national essence” than the communists. Surrendering to the Americans, he reasoned, might be the only way to save the kokutai.

But Japan was not a country where one could speak this way with impunity. Two months later, two former officials and a journalist who had helped prepare the “Memorial,” including former prime minister Yoshida Shigeru, were arrested. Yoshida was imprisoned for forty-five days and forced to apologize: “Not having thought the matter through sufficiently, I slandered the military, and for this I offer my sincere apologies. I hope you will excuse me on this point. Henceforth I shall revise my mental attitude, and desire to cooperate as a subject in the execution of this war.”46

In April 1945, Admiral Suzuki Kantarō became prime minister. Several commentators have claimed that the emperor ordered Suzuki to make peace. Suzuki himself, however, said at his war crimes trial that he “did not receive any direct order from the Emperor” to end the war—only that he had somehow understood that that was what the emperor wanted. Robert Butow notes that, in reference to discussions leading up to the forming of the Suzuki government, one adviser said: “Suzuki could not just openly declare he was going to end the war, but (and it was a significant ‘but’) that was clearly his intention.” Suzuki, however, signed statements as prime minister pledging to mobilize the nation for a last charge—so that “the one hundred million” (shorthand for the seventy million Japanese subjects) would throw their bodies forward in defense of the emperor.47 On June 6, Suzuki had supported the “Fundamental Policy”—that every man, woman, and child should fight to the death. These were his real intentions. The emperor himself issued a rescript on June 9, 1945, ordering his subjects to “smash the inordinate ambitions of enemy nations” and “achieve the goals of the war.”48

It is the actions of these men that matter, not their alleged inner thoughts. They actively, repeatedly, and over years promoted the deaths of millions, as a matter of policy and of deep-seated commitment. After the American victory they claimed to have wanted to end the war—the emperor most of all—but no one said it openly at the time, least of all the emperor.

In mid-1945, the government continued to disavow any statement that even hinted at an entreaty to peace. When a Japanese military attaché to Sweden insinuated that peace might be sought by Japan, the Tokyo government corrected the statements: “As we have said before, Japan is firmly determined to prosecute the Greater East Asia war to the very end.”49

While the Japanese leadership remained committed to the war, the United States began to fulfill its promise of “prompt and utter destruction.” On August 6, 1945, the city of Hiroshima was obliterated by a uranium fission bomb. (The first—by milliseconds—of more than one hundred thousand to die were officers in the Japanese Second Army Group, who would have commanded the anticipated suicide charge in southern Japan.) President Truman issued a statement that day, subsequently dropped as leaflets on Japan: If the Japanese leaders did not accept the Potsdam ultimatum, “they may expect a rain of ruin from the air, the like of which has never been seen on this earth.”50

The atomic bomb was an unprecedented shock to the Japanese leadership. Prior to Hiroshima, General Anami had maintained that the United States had no such bomb. The Japanese Technology Board had advised that even if Americans had such a bomb, the “unstable” device could not be transported across the Pacific.51 Once the bomb fell, its existence—and the American will to use it—could not be denied. Still, Anami refused to give up hope for an invasion and claimed that the Hiroshima bomb was the only one the Americans had.

On August 7, the emperor may have expressed his desire, in private, to his chief aide, Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal of Japan Kido Koichi, to bring about an end to the war, to “bow to the inevitable” in order to avoid “another tragedy like this.” This alleged desire of the emperor was revealed in Kido’s later recollections, which were likely self-sacrificial statements made by him with the intention of protecting the emperor from prosecution as a war criminal.52 Whether or not the emperor desired to end the war after the Hiroshima bomb, the fact remains that he chose neither to do nor to say anything to end the war. Even after Hiroshima, the Big Six remained deadlocked—and the emperor, silent.

On August 8, two days after Hiroshima, the Russians attacked Japanese positions in Asia, where six million Japanese troops and civilians were stationed. Both Roosevelt and Truman had urged Stalin to enter the Asian war in order to open a second front against Japan and to prevent the return of Japanese troops to the main islands. Russia’s overwhelming attack also threatened Japan’s northern islands with Soviet occupation, which would likely be followed by the communist revolution the Japanese leadership feared. Still, Japan did not surrender.

On the morning of August 9, 1945, at 10:30 a.m.—three days after Hiroshima—the Big Six again convened. Anami continued to argue against any form of capitulation. He maintained that the Americans had no other atomic bombs, an understandable conclusion for him, since he would have used them immediately had he been in their shoes. In the interpretation of historian Sadao Asada, Anami became “almost irrational,” declaring, in essence: “The appearance of the atomic bomb does not spell the end of war. . . . We are confident about a decisive homeland battle against American forces. . . . [T]here will be some chance as long as we keep on fighting for the honor of the Yamato race.”53 In his mind, millions of Japanese men, women, and children could still save the “national essence”—if only they had the will to fight and die.

Word of the bombing of Nagasaki came while the Big Six were in recess. When they reconvened at 2:30 p.m., Anami had revised his position again. He had first denied that the Americans had an atomic bomb, and later conceded that they had one. Now, in the wake of Nagasaki, he admitted that the United States might have one hundred atomic bombs and could drop three every day. Prime Minister Suzuki and others came to believe that the Americans, instead of invading of Japan, would just keep dropping atomic bombs. Anami, Suzuki, Tōgō, and their fellows were finally forced to recognize reality—that the Americans were willing and able to remain offshore and bomb Japan into the bedrock. The rumor spread that Tokyo was to be next, on August 12, three days after Nagasaki.

This complete loss of hope was vital to forcing Japan’s decision to surrender. As long as the leadership saw even a slim chance of preserving their system, they would grasp at that chance. They had hoped desperately for an American land invasion, but that hope dissipated with the incendiary attacks and atomic bombs. There would be no chance to preserve their system: no great battle, no Banzai charge, no honor, no “Nation” to live on—only “prompt and utter destruction.”

The Big Six met until 10:00 p.m.—but remained deadlocked. Three of the six were willing to accept the Potsdam declaration, with the proviso that the imperial house be maintained. The other three—including General Anami—demanded further conditions that would have preserved the position of the military in Japan. With no decision possible, Prime Minister Suzuki requested a meeting late that evening—in the emperor’s presence. The emperor, in full dress uniform, heard Foreign Minister Tōgō argue for the acceptance of Potsdam, and Army Minister Anami argue against it. Suzuki then stepped forward and made an unprecedented request: that the emperor decide. Until this point, the emperor had always confirmed only what the Big Six had unanimously agreed upon.

In making his “sacred decision,” the emperor chided the army for its failure and noted that the new and terrible bombs would bring only suffering to the Japanese people. He accepted that events did not allow the war to continue—and he expressed his wish for Japan to accept the Potsdam Declaration. This open admission of defeat was vital to securing the organized surrender of millions of Japanese troops—but even with the emperor’s wish for surrender, Anami later had to threaten rebellious officers that anyone who attempted to disrupt the surrender “will have to cut me down first.”54

On August 10, while thousands of U.S. planes bombed Tokyo and other cities, Japanese leaders sent word to the Americans that they would accept the Potsdam ultimatum—but that the imperial house was to remain sovereign over Japan. The next day, August 11, the Americans replied that the emperor would be subject to their orders. This signaled the American intent to preserve the emperor as sovereign—while subordinating him and his subjects to the will of the Americans.

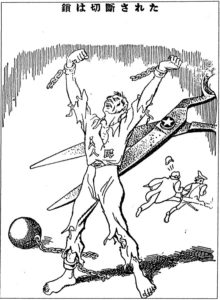

On August 14, the Japanese government accepted the Potsdam ultimatum, thereby surrendering to the United States. This political decision to submit to the will of the victors had yet to be communicated to the army and the populace. On August 15, for the first time in history, the emperor’s recorded voice emanated from radios across Japan. He told his subjects that circumstances had not turned out to their advantage—again blaming the army for failing to prevail—and that they would have to “endure the unendurable.” His subjects bowed before the radios and wept—many in relief, they having expected the emperor’s broadcast to be a call to fight to their deaths. For millions of Japanese, the meaning of the American victory was liberation from death. Physically, and psychologically, they were given back their lives.55

The American decision to retain the emperor has been widely criticized—and with good reason. Emperor Hirohito was very aware of war planning; during the fervent war years, he was apprised regularly of Japan’s military resources, sometimes seeing multiple drafts of statements and orders.56 He repeatedly expressed his desire for further military conquest. He ordered his people to prepare for suicidal charges in his name. He could have expressed a wish to end the war earlier, and forced the leadership to confront the need for surrender. He did not. He was a war criminal if anyone was, and he deserved to be executed if anyone did.

But as a means of achieving a full and organized surrender, the decision was appropriate. The Japanese people overwhelmingly wanted to retain their imperial system, and American leaders knew that to demand its destruction would likely result in a communist insurgency and civil war. Retaining the emperor did not mean that Japan was to be ruled by a Prussian-style all-powerful autocrat. Instead, the emperor was to become a British-style figurehead, subordinated to American will and then constitutionally neutered.

The emperor accepted his new position fully. On September 2, 1945—the day the Japanese surrender was signed on the deck of the battleship USS Missouri—the emperor made his commitment to the surrender public. He issued a rescript commanding his subjects “to lay down their arms and faithfully carry out all the provisions of the instrument of surrender.”57 During the occupation to come, he denied his status as a deity, accepted a new political constitution, and remade himself into a private man, expressing his desire to return to his chosen field of study, marine biology.

As for Army Minister Anami: Given the emperor’s sacred decision to end the war, Anami was trapped between his loyalty to the imperial throne and his sympathy for junior officers who shared his Bushido ideal of fighting to the end. Some officers demanded that the emperor be replaced with someone who might better promote the “national essence” by prosecuting the war. But Anami refused to countenance such a coup, and thereby prevented a potentially devastating military rebellion. The morning after the acceptance of Potsdam, Anami committed the final act toward which his entire life had been oriented: He committed suicide, by disemboweling himself, leaving behind a poem of apology to the emperor for his “great crime.”58

The shock of the air attacks—and the intransigence of the United States in its demands—had made the issue of surrender an either–or proposition for the Japanese. Sixty years of indoctrination had created a cultural straitjacket that could be removed by nothing less than such power and intransigence. It blew apart like a threadbare fabric that had restrained its victims by no means other than their unwillingness to cast it aside. Freed from Anami and his suicidal ideology, the Japanese could, with American guidance, remake themselves and their country with values that affirmed their newfound desire to live.

The Occupation

During the six years and eight months following their surrender, from September 2, 1945, until April 1952, the Japanese lived under American military occupation, commanded by the Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers (SCAP). Until March 1951, this was General Douglas MacArthur. All of Japan was under American control; there was no division of the country, no “Communist North Japan.” The Japanese were strictly censored and placed under tight economic control until fundamental reforms had taken hold. Their government, their religious shrines, and their schools were subordinated to American diktat. SCAP’s mission was to enforce the surrender and to eliminate the possibility that Japan would again threaten the world.59

To reiterate, during the occupation not one American soldier was killed in Japan as the result of hostile action. There were no insurgencies or terror campaigns, nor was there international pressure to “give Japan back to the Japanese.” In mid-1945, when 500,000 troops were considered necessary for the occupation, MacArthur was criticized for saying that in six months only 200,000 troops would be needed. But he was correct—and that number fell to 102,000 by 1948. As MacArthur reported: “In the accomplishment of the extraordinarily difficult and dangerous surrender in Japan, unique in the annals of history, not a shot was necessary, not a drop of Allied blood was shed.”60

MacArthur’s initial orders were found in the “ Basic Initial Post Surrender Directive to Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers for the Occupation and Control of Japan,” which was issued by the Joint Chiefs of Staff and based on the Potsdam Declaration:

The basis of your power and authority over Japan is the directive signed by the President of the United States designating you as Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers and the Instrument of Surrender, executed by command of the Emperor of Japan. These documents, in turn, are based upon the Potsdam Declaration of 26 July 1945, the reply of the Secretary of State on 11 August 1945 to the Japanese communication of 10 August 1945 and the final Japanese communication on 14 August 1945. Pursuant to these documents your authority over Japan, as Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers, is supreme for the purpose of carrying out the surrender. . . .

As Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers your mission will be to assure that the surrender is vigorously enforced and to initiate appropriate action to achieve the objectives of the United Nations. . . .

There must be eliminated for all time the authority and influence of those who have deceived and misled the people of Japan into embarking on world conquest, for we insist that a new order of peace, security and justice will be impossible until irresponsible militarism is driven from the world.

The occupation began with an open recognition of the status of the Japanese as a defeated people. This concept of defeat, driven deeply into the bedrock of the Japanese mind, established an entirely one-sided relationship with the Americans. The occupation was forced upon the Japanese; it was not the result of negotiations with them. The initial order continued:

By appropriate means you will make clear to all levels of the Japanese population the fact of their defeat. They must be made to realize that their suffering and defeat have been brought upon them by the lawless and irresponsible aggression of Japan, and that only when militarism has been eliminated from Japanese life and institutions will Japan be admitted to the family of nations.61

All attempts by the Japanese to bargain were cut off. When Japanese officials stated to Truman their desire to control their own foreign embassies, he replied that all instructions “will be communicated by the Supreme Commander at appropriate times determined by him.” There was to be no appeal to Washington over MacArthur’s head. When Japanese officials tried to instruct the Americans as to the best way to occupy Japan—by keeping American troops out of Tokyo, by letting the Japanese disarm themselves, by allowing officers to keep their ceremonial swords, and by dispatching food immediately—President Truman correctly identified this as an attempt by the defeated to bargain with the victors as equals. He issued this clarification to MacArthur:

[Y]ou will exercise your authority as you deem proper to carry out your mission. Our relations with the Japanese do not rest on a contractual basis, but on unconditional surrender. Since your authority is supreme, you will not entertain any questions on the part of the Japanese as to its scope.62

Under the occupation, all Japanese laws were subordinated to American military command, and the United States would not accept any suggestions as to its limits. SCAP’s supreme authority had been established and defined in the Potsdam Declaration, in the Japanese and American communication that followed it, in the Instrument of Surrender signed by the emperor, and in two post-surrender orders. (During the international war crimes trials in Japan, America did, to some extent, bend to international pressure and accept the forums of “international law,” but this was never allowed to circumvent the authority of SCAP.) The final authority in Japan during the occupation was SCAP.

Unconditional surrender was entirely different from an armistice agreement reached by negotiations. Unconditional surrender began with a demand; the alternative was surrender or death, not a choice between negotiating points. There was no contract between the Americans and the Japanese, no negotiated agreements, and no supervening authority over the Americans. There could be no claims that the Americans had violated any contract, akin to the claims to mistreatment raised by the Germans after World War I in Europe.

This American dominance over a vanquished people was overwhelmingly accepted within the U.S. government—and those who misunderstood the situation could find themselves sidelined. During one top-secret meeting, a high-level State Department official with a long history of service in Japan suggested that “international law” applied to the occupation, which he claimed was a contract between Japan and the United States. The Japanese, he said, had not really surrendered unconditionally given this verbiage of the Potsdam Declaration: “the following are our terms.” Within three days he was replaced with someone who understood the policy.63 The Americans were as intransigent in their enforcement of unconditional surrender as they had been in achieving it.

Part of the meaning of unconditional surrender was that the Americans assumed no responsibility for the welfare of the defeated Japanese. The initial orders to MacArthur made this clear:

13. You will not assume any responsibility for the economic rehabilitation of Japan or the strengthening of the Japanese economy. You will make it clear to the Japanese people that:

a. You assume no obligations to maintain, or have maintained, any particular standard of living in Japan, and

b. That the standard of living will depend upon the thoroughness with which Japan rids itself of all militaristic ambitions, redirects the use of its human and natural resources wholly and solely for purposes of peaceful living, administers adequate economic and financial controls, and cooperates with the occupying forces and the governments they represent.64

Given the starvation in countries that Japan had raped, the Japanese had no special right to food. The Americans actually charged the Japanese for many costs of the occupation.65 But MacArthur soon became an ardent advocate for American aid, which eventually totaled more than twenty billion dollars. He also opposed reparations, demanded by some nations, in the form of moving industrial machinery.66 He recognized that it was in American self-interest to see Japan achieve prosperity and to prevent its looting by other nations. But the essential point is that the surrender came first, before any aid. Prior to the surrender, the Americans dropped napalm and atom bombs, not food, on Japanese civilians.