This letter and reply are from the Spring 2012 issue of TOS.

This letter and reply are from the Spring 2012 issue of TOS.

To the Editor:

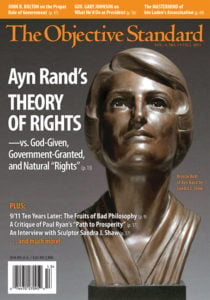

I must take issue with part of Craig Biddle’s article “Ayn Rand’s Theory of Rights” [TOS, Fall 2011]. Mr. Biddle is right to distinguish Rand’s view of rights from both the religious notion that we are endowed with rights by God and the positivist argument that rights are government-created permissions. But his attempt to distinguish Rand’s view from natural rights theories is unconvincing. He characterizes this third category of rights theory as the view “that rights come from a law of nature created by God,” and he notes that this amounts to the first category—the religious argument.

But as Mr. Biddle’s article makes clear, Rand does believe that rights come from a law of nature—just not one rooted in religious faith. He acknowledges that she invokes a “moral law . . . [that is] the principle of egoism,” and he analogizes this moral law to the principles of the hard sciences: “Just as the abstract nature of the principles of physics and biology does not change the fact that those principles are true, so, too, the abstract nature of the principles of morality does not change the fact that these principles are true.” But the principles of physics or biology refer to natural phenomena, and surely Mr. Biddle would not hesitate to refer to them as “laws of nature.”

Rand roots her view in the observed facts of man’s nature and observable, natural reality: Human beings are of such a nature that their existence naturally depends on certain conditions. Her view is a genuinely natural rights theory.

I believe that it would be more profitable for Objectivists to reject the efforts of writers such as John Finnis, Hadley Arkes, or Robert George to co-opt the term “natural” for their supernatural rights theories than to discard the distinguished term “natural rights,” to which Objectivists have a superior claim.

—Timothy Sandefur , Sacramento, California

The writer is a principal attorney at the Pacific Legal Foundation.

Craig Biddle replies:

I appreciate Mr. Sandefur’s letter, and I’m sorry to hear that he found unconvincing my argument that Ayn Rand’s theory of rights is not properly regarded as a “natural rights” theory.

As I discussed in my article, Rand’s theory is distinct not only from “man-made rights” and “God-given rights” theories—and not only from “natural rights” theories that actually amount to “supernatural rights” theories (which Mr. Sandefur notes that I addressed)—but also from “natural rights” theories that refer to so-called “inherent rights.” I addressed this in my article as well (see pp. 31–32 and endnotes 45 and 46), but it is an important subject, so I’m happy to elaborate here.

In addition to the problem that “natural rights” theory has historically referred exclusively (or near exclusively) to God-given rights theory, there is the problem, as I put it in my article, that

“natural rights” theory holds that rights are “inherent” in man’s nature—meaning, “inborn” and a part of man by virtue of the fact that he is man. But rights are not inherent or inborn—which is why (a) there is no evidence to suggest that they are, and (b) belief that they are is mocked as “one with belief in witches and unicorns.”

Rand’s theory holds not that rights are “inherent,” but that they are objective—not that they are “inborn,” but that they are conceptual identifications of the factual requirements of human life in a social context.

Rights don’t exist in man, like bones or lungs. Rights are not physical existents or physical processes but mental integrations of observed facts. This is why they are properly regarded not as “natural,” but as objective. A few analogies may help.

Tigers are natural; they exist in nature whether or not man recognizes their existence. But the concept of “tigers” is not natural; it does not exist in nature. Rather, the concept of “tigers” is objective; it is a mental integration of perceived entities in nature. Both parts—the mental integration and the entities in nature, consciousness and existence, the mind and the referent, the “in here” and the “out there”—are necessary for a concept to exist and be valid.

Likewise for principles: Things are what they are, whether or not man recognizes this fact, but the fact alone is not a principle; the fact alone is not the law of identity. The law of identity, the principle, comes into existence only when man mentally integrates his observations of the world into a fundamental generalization: Everything is something specific; everything has properties that make it what it is; everything has a nature—a thing is what it is. The principle is not “natural” but objective.

Likewise for theories: Evolution is a fact of nature—the process occurs whether or not man recognizes it. But the fact or process of evolution alone is not a theory. The theory of evolution comes into existence only when a man (in this case Darwin) mentally integrates a massive amount of observed data into a system of concepts, generalizations, and principles. The theory is not “natural”; it is objective—it is a mental integration (consciousness) of many observed facts (existence).

Likewise for the principle of rights and for Rand’s theory of rights: Man’s need of freedom in order to act on his judgment is a fact of nature, and it is so whether or not man recognizes the fact. If man is enslaved he cannot act on his judgment, thus he cannot live as a rational being. But until man recognizes this fact, until he forms a fundamental generalization to the effect that “in order to act rationally, in accordance with man’s nature, man must be free to act on his judgment,” there is no principle of rights.

Rand did not merely formulate the principle of rights. She integrated a massive number of observations, concepts, generalizations, and principles from all the basic branches of philosophy into a demonstrably true theory of rights (see my article for details). At every stage of development, she observed facts (existence) and made mental integrations (consciousness). And the rights that her theory set forth are not mere facts of nature; they are recognitions of facts of nature. Her theory and the rights it validates are not “natural” but objective.

Rights do not exist in nature apart from man’s consciousness; to hold that they do is to commit the error of intrinsicism. Nor do rights exist in man’s consciousness apart from nature; to hold that they do is to commit the error of subjectivism. Rights are conceptual identifications of certain facts of reality; this makes them objective. (For a discussion that parallels this point, see Rand’s essay “What is Capitalism?” [in Capitalism: The Unknown Ideal] in which she discusses “three schools of thought on the nature of the good: the intrinsic, the subjective, and the objective.”)

Rights do not exist in nature apart from man’s consciousness; to hold that they do is to commit the error of intrinsicism. Nor do rights exist in man’s consciousness apart from nature; to hold that they do is to commit the error of subjectivism. Rights are conceptual identifications of certain facts of reality; this makes them objective. (For a discussion that parallels this point, see Rand’s essay “What is Capitalism?” [in Capitalism: The Unknown Ideal] in which she discusses “three schools of thought on the nature of the good: the intrinsic, the subjective, and the objective.”)

This is why Rand spoke of rights as being “derived from [man’s] nature as a rational being” but never as inherent in man’s nature. It’s also why she never referred to her theory of rights as a “natural rights” theory. (It’s worth noting that in her article “The Only Path To Tomorrow” [Reader’s Digest, January 1944], Rand did refer to rights as being “granted to [man] by the fact of his birth.” But this was before she had fully developed her philosophy, and, to my knowledge, she never put it that way again.)

Mr. Sandefur notes that I wrote, “Just as the abstract nature of the principles of physics and biology does not change the fact that those principles are true, so, too, the abstract nature of the principles of morality does not change the fact that these principles are true.” He then comments, “But the principles of physics or biology refer to natural phenomena, and surely Mr. Biddle would not hesitate to refer to them as ‘laws of nature.’” This is correct. The principles of physics and biology refer to facts of nature. The facts themselves, however, are not laws or principles. The laws or principles are mental integrations of facts. For facts to become a law or principle, someone has to conceptually integrate them.

Historically, “natural rights” theory has referred exclusively to “God-given” rights and/or “inherent” (aka “innate” or “intrinsic”) rights. This fact alone is sufficient to disqualify the phrase as descriptive of Rand’s theory. The stronger point, however, is that Rand’s is a theory not of “natural rights” but of objective rights.

I sympathize with Mr. Sandefur’s desire to term Rand’s theory of rights a “natural rights” theory. That label would make her theory instantly more appealing to a large number of people. The problem is that if people embrace her theory under the impression that it’s a natural rights theory, they do not understand and are not embracing her theory.

That objective rights theory may be more difficult to explain and less appealing to some people than “natural rights” theory is doesn’t change the fact that rights are not “natural” but objective. Egoism, too, can be difficult to explain and is certainly less appealing to many people today than the muddled yet widely accepted “golden rule,” but we still must advocate egoism if we are to advocate the truth.

—Craig Biddle, Editor

Related:

- Ayn Rand's Theory of Rights: The Moral Foundation of a Free Society

- A Civilized Society: The Necessary Conditions

![[TEST] The Objective Standard](https://test.theobjectivestandard.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/logo.png)