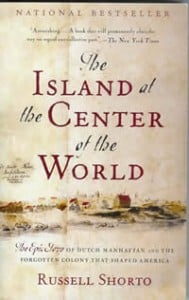

The Island at the Center of the World, by Russell Shorto. New York: Vintage Books, 2004. 384 pp. $14.95 (paperback).

“[E]ach person shall remain free, especially in his religion, and . . . no one shall be persecuted or investigated because of their religion” (p. 96).

Those words evoke America’s revolutionary era, but they were penned two centuries earlier. They are part of the Dutch de facto constitution, the Union of Utrecht, drafted in 1579 after thousands of Dutchmen had suffered religious persecution by the Spanish in the form of torture and death. To Russell Shorto, a writer for The New York Times Magazine, these words speak directly to the “tolerance” embodied by the 17th-century Dutch Republic and its colonies, particularly the island colony of Manhattan, or New Amsterdam, after English explorer Henry Hudson claimed the land for the Netherlands in 1609.

In The Island at the Center of the World, Shorto’s enlightening book about this period, he writes: “This sentence became the ground on which the culturally diverse society of the seventeenth century was built” (p. 96).

In a later chapter titled “Booming,” Shorto notes that when religious groups, particularly the Jews, were persecuted in New Amsterdam, they appealed to the republic’s freedom-of-conscience law; and others, led by the Quakers, signed the Flushing Remonstrance, a document that stated “love peace and libertie . . . which is the glory of the Outward State of Holland” extends even “to Jewes Turkes and Egiptians” (p. 276). Shorto regards this document as a key link between the motherland’s constitution and America’s founding ideals.

The so-called Flushing Remonstrance is considered one of the foundational documents of American liberty, ancestor to the first amendment in the Bill of Rights. . . . If the first amendment hearkens back to the Flushing Remonstrance, the Flushing Remonstrance clearly bases itself on the religious freedom guarantee in the Dutch constitutional document. (p. 276)

Shorto can confidently assert these connections, in part because his book weds the histories of the 17th-century Dutch settlement of New York to the most recent, thorough, and competent translations of the colony’s twelve thousand surviving archival documents, including letters, records of court proceedings, and wills. These documents unveil facts about the Dutch people’s ideas, culture, and governance, including freedom of conscience, which helped shape the city and the United States but rarely, if ever, saw the historical light of day in books that otherwise centered on Puritans and America’s so-called religious foundations. Shorto demonstrates persuasively that the Dutch people’s cultivation of a multinational, multireligious colony is an important yet unheralded legacy of New Amsterdam. And he shows that this legacy is an outgrowth of the motherland’s religious freedom.

Seventeenth-century Holland was Europe’s melting pot, and a haven for those who had suffered religious persecution in their native lands, including English Pilgrims. The Puritans were among the persecuted sects that found religious freedom in New Amsterdam during the 1640s, a “genuine rarity in the era,” Shorto writes (p. 159). Dutch religious pluralism was a conduit for cultural pluralism, and Manhattan’s village of Harlem serves as a microcosm that foreshadowed America’s melting pot to come:

The initial bloc of thirty-two families who staked out lots along its two lanes came from six different parts of Europe—Denmark, Sweden, Germany, France, the Netherlands, and what is now southern Belgium—and spoke five different languages. Perched alongside one another on the edge of a wilderness continent, families that would have broken up into ghettos in Europe instead had to come together, and learned a common language.

Nothing better shows the kind of mixing that took place in this setting than a phenomenon that was unprecedented elsewhere in the colonies: intermarriage. Scan the marriage records of the Dutch Reformed Church of New Amsterdam and you find a degree of culture-mixing in such a small place that is remarkable for the time. A German man marries a Danish woman. A man from Venice marries a woman from Amsterdam. . . . In all, a quarter of the marriages performed in the New Amsterdam church were mixed. . . . and there are instances of marriage between whites and blacks. (p. 272)

Shorto redresses the historical accounts that prevailed after Britain wrested control of Manhattan from the Dutch in 1664, which emphasize the alleged religious origins of the United States, portray New England’s Puritans and Pilgrims as models, and cast the Dutch as bit players. As he navigates the history of New Netherland, a province that spanned from Albany to the Delaware Bay, he reacquaints readers with familiar subjects while introducing them to others relegated to obscurity.

Familiar subjects include Henry Hudson; the Dutch purchase of Manhattan island from the Indians for $24; and Peter Stuyvesant, the colony’s peg-legged autocratic director who established the first municipal government there in 1653. An example of the obscure subjects is Adriean van der Donck, an attorney who challenged the colony’s directors, in part by fighting for home rule and particular rights.

Shorto sees Van der Donck’s writings as the jewel of the recently translated Dutch archives, and he presents the colony’s only jurist as a hero deserving the status of an early American patriot. Van der Donck’s heroism is shown via stories such as his taking up protesters’ grievances when William Kieft, Stuyvesant’s similarly autocratic predecessor, proposed a tax on beaver pelts and beer. Shorto sets the stage:

[H]ere, in the capital of the Dutch province, was a genuine cause in the making, a political struggle at the cutting edge of legal thought. What rights did individuals have in an overseas outpost? Were they entitled to the same representation as citizens in the home country? Never before had an outpost of a Dutch trading company demanded political status? (p. 142)

Van der Donck’s letter to the Netherlands argued against what was, in effect, taxation without representation (p. 144) and decried that one man could “dispose here of our lives and properties at his will and pleasure.” Van der Donck called for Kieft’s replacement and a new system of governance in which villagers elect representatives who, in turn, vote on public affairs, “so that the entire country may not be hereafter, at the whim of one man, again reduced to similar danger” (p. 144).

Although his campaigns for rights and representative government were ultimately ignored, van der Donck continued to champion these ideals, even as his banishment from the colony or execution became more likely.

Shorto writes that van der Donck is a pivotal subject, “the man who, more than any other, and in many ways that have gone unnoticed, mortared together the foundation stones of a great city” (p. 143).

Later, when Britain took control of New Netherland, the Dutch were neither banished nor forgotten, as Shorto contends most observers mistakenly believe. Remarkably, the Article of Capitulation, the Dutch surrender to Britain, allowed the two trading empires to coexist in Manhattan, rendering it a dual port. The English granted the Dutch freedom of conscience, most Dutch families remained in the colony, and more Dutchmen than ever left Holland to settle there. Most notably, though, the Dutch people’s political influence extended into America’s founding era. Of the twenty-six men from New York’s delegation at the Constitutional Convention that insisted on a Bill of Rights, half were Dutch.

In a chapter titled “Inherited Features,” Shorto expounds on these and other less-known historical facts and suggests that their omissions from popular histories are not necessarily oversights:

Subsequent generations were raised on the belief that America’s origins were English, and that other traditions wove themselves into the fabric later. And history shows this, does it not? The thirteen original colonies were English colonies. The supporting evidence is overwhelming: the language we speak, our political traditions, many of our customs. This is all so obvious that we don’t question it.

But it ought to be questioned. The original colonies were not all English, and the multiethnic makeup of the Manhattan colony is precisely the point. The fact that the Dutch once established a foothold in North America has been known all along, of course, but after noting it, the national myth of origin promptly dismisses it as irrelevant. It was small, it was short lived, it was inconsequential. (p. 302)

In The Island at the Center of the World, Shorto treads carefully in an effort to not overstate the influence and contributions of the Dutch in shaping New York and the nation at large. He even acknowledges that their system “wasn’t built to last” (p. 284). Although certain 17th-century Dutchmen upheld representative government and free trade, Shorto recognizes that philosophically the Dutch were unable to establish a constitutional republic based on each individual’s inalienable rights to life, liberty, and pursuit of happiness.

Nevertheless, his readers will learn that the Dutch colony centered in Manhattan played an important role in developing and employing those ideals, even if only implicitly, and thereby helped construct the foundations for what later would become the first truly free nation in history. Shorto establishes this message as the purpose of this book, and he succeeds in spades.

![[TEST] The Objective Standard](https://test.theobjectivestandard.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/logo.png)