With this week’s DVD release of Star Trek into Darkness, now is a good time to evaluate or reevaluate the oft-stated Star Trek claim, “The needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few” (or “the one”). This claim is made in various scenes in the films, including in the latest one. Let’s first consider some instances and the relevant contexts.

With this week’s DVD release of Star Trek into Darkness, now is a good time to evaluate or reevaluate the oft-stated Star Trek claim, “The needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few” (or “the one”). This claim is made in various scenes in the films, including in the latest one. Let’s first consider some instances and the relevant contexts.

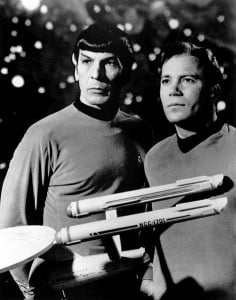

In The Wrath of Khan (1982), Spock says, “Logic clearly dictates that the needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few.” Captain Kirk answers, “Or the one.” This sets up a pivotal scene near the end of the film (spoilers follow).

With the Enterprise (ship) in imminent danger of destruction, Spock enters a highly radioactive chamber in order to fix the ship’s drive so the crew can escape danger. Spock quickly perishes, and, with his final breaths, says to Kirk, “Don't grieve, Admiral. It is logical. The needs of the many outweigh . . .” Kirk finishes for him, “The needs of the few.” Spock replies, “Or the one.”

In the next film, The Search for Spock (1984), the crew of the Enterprise discovers that Spock is not actually dead, that his body and soul survive separately, and that it may be possible to rejoin them—which the crew proceeds to do. Once restored, Spock asks Kirk why the crew saved him. Kirk answers, “Because the needs of the one outweigh the needs of the many.” This is, as Spock might say, a fascinating reversal of the message in the previous film.

How can these ideas be reconciled?

We find an answer in the next film, The Voyage Home (1986). At the beginning of this film, Spock’s mother, who is human (his father is Vulcan), asks him whether he still believes that, by logic, the needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few. He says yes. She replies, “Then you are here because of a mistake—your friends have given their future to save you.” (The crew had broken the law and had gone on the run in order to rescue Spock.) Spock says that humans are sometimes illogical; his mother answers, “They are, indeed!”

Later in the film, when crewman Chekov is in trouble, Spock insists that the crew save him, even at risk of jeopardizing the crew’s vital mission to save Earth and everyone on it. Kirk asks, “Is this the logical thing to do?” Spock answers, “No, but it is the human thing to do.” Although Spock reaffirms his claim that the needs of the many logically outweigh the needs of the few, he suggests that sometimes we must do the “human” thing, not the logical thing, and put the needs of the few (or the one) first.

So Spock, Kirk, and Spock’s mother have affirmed the idea that acting logically and acting “human” can be at odds—and that acting logically means always putting the needs of the many first. This is the alleged reconciliation of the apparently conflicting ideas with which we started.

But this logically is not a reconciliation at all.

In logic, (a) there can be no divide between acting logically and acting human; and (b) as Ayn Rand discovered and explained, the needs of the individual are what give rise to the need and possibility of value judgments to begin with.

Our capacity to use logic, to integrate the evidence of our senses in a noncontradictory way, is part of our rational faculty—the very faculty that makes us human. Obviously, we also have the capacity to be illogical, but that is because our rational faculty also entails volition, the power to choose to think or not to think. We also have the capacity to experience emotions, which are automatic responses to our experiences in relation to our values. (Various other species have an emotional capacity as well, but our values are chosen, so even on this score we are substantially different.)

Our emotions, though real and important, are not a means of knowledge; they are automatic reactions to experiences in relation to our value judgments. Our means of knowledge is reason, the use of observation and logic.

In regard to the Star Trek example, the reason Kirk was right to help Spock is not that doing so was “human” as against “logical”; rather, he was right to help Spock because, given the immense value that Spock is to Kirk, both as a friend and as a colleague, and given that the mission to help Spock was feasible, helping him was the logical and thus human thing to do.

In this case, Kirk’s emotional ties to Spock aligned with his logical evaluation of Spock’s value to him. It is possible for a person’s values to be out of line with his rational judgment, but in such cases his rational judgment remains his means of knowledge, and his emotions should take a backseat until he reassesses his values and brings them back into line with his logical assessment of the facts.

Once we see the relationship and potential harmony between reason and emotion, we can see that Spock’s claim that being logical is (or can be) at odds with being human makes no sense.

What of Spock’s claim, “Logic clearly dictates that the needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few”? Logic requires that some evidence be offered in support of such a claim—but Spock offers no evidence in support of this. He just asserts it. Which “many”? Which “few”? “Outweigh” on whose scale? For what purpose? To whose benefit? Why is his or their benefit the proper benefit? Spock does not address such questions; he simply asserts that logic clearly dictates his conclusion. But it doesn’t.

Far from being an expression of logic, Spock’s claim that the needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few is an arbitrary assertion and a restatement of the baseless moral theory known as utilitarianism, which asserts that each individual should act to serve the greatest good for the greatest number. (For a critique of utilitarianism, see my essay on the moral theory of Sam Harris, TOS, Winter 2012–13.)

What logic actually dictates is that if human beings want to live and achieve happiness, they must identify and pursue the values that make that goal possible. As Ayn Rand points out, life makes values both possible and necessary. We need to eat—in order to live and prosper. We need to wear protective clothing and find shelter—in order to live and prosper. We need to pursue a productive career to gain goods and services—in order to live and prosper. The principle holds true in more-complex cases as well. We need to build friendships to gain a wide variety of intellectual, psychological, and material benefits—in order to live and prosper. We need to experience great art to see our values in concrete form—in order to live and prosper. The pattern holds for all our values. Logically, the only ultimate reason we need to pursue any value is in order to live and prosper. (See Rand’s essay “The Objectivist Ethics” for her derivation of this principle.)

What logic actually dictates is that if human beings want to live and achieve happiness, they must identify and pursue the values that make that goal possible. As Ayn Rand points out, life makes values both possible and necessary. We need to eat—in order to live and prosper. We need to wear protective clothing and find shelter—in order to live and prosper. We need to pursue a productive career to gain goods and services—in order to live and prosper. The principle holds true in more-complex cases as well. We need to build friendships to gain a wide variety of intellectual, psychological, and material benefits—in order to live and prosper. We need to experience great art to see our values in concrete form—in order to live and prosper. The pattern holds for all our values. Logically, the only ultimate reason we need to pursue any value is in order to live and prosper. (See Rand’s essay “The Objectivist Ethics” for her derivation of this principle.)

How does this principle apply in the Star Trek examples? In the case of Kirk’s dangerous mission to help Spock, Kirk logically concludes that, given the full context of his values, saving his dear friend is worth the risk involved.

What are we to make, then, of Spock’s final actions in The Wrath of Khan? Does he sacrifice his own life and values in order to serve the needs of the many? No. Khan, piloting a damaged ship, sets off a device that will soon cause a massive explosion that will destroy his own ship along with the Enterprise and its entire crew. Captain Kirk says to his chief engineer, “Scotty, I need warp speed in three minutes or we’re all dead.” It is at this point that Spock leaves the bridge, goes to engineering, and enters a radiation-filled room in order to repair the ship’s warp drive. As a result of Spock’s actions, the Enterprise speeds away to a safe distance from the explosion—but Spock “dies.”

Spock does consider the needs of his friends and shipmates in making this move. But he does not thereby sacrifice his own values or even his own life. His only alternative is to die with the ship anyway. Instead of dying and having all of his shipmates and friends die too, he chooses to uphold and protect the values that he can and to uphold his commitment to serve as a Star Fleet officer—a position that he chose knowing and accepting the risks involved.

Although in this case Spock must pick the least bad of two bad options, he makes the choice that best serves his interests and thus his life.

The only principle consistent with logic and thus with humanity is that if we want to “live long and prosper” (as Vulcans often say) we must use logic and pursue our life-serving values. Fortunately, contrary to Spock’s occasional illogic, this is what he actually does. And this is why so many people love him. It’s only logical.

Like this post? Join our mailing list to receive our weekly digest. And for in-depth commentary from an Objectivist perspective, subscribe to our quarterly journal, The Objective Standard.

Related:

Image: Wikimedia Commons

![[TEST] The Objective Standard](https://test.theobjectivestandard.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/logo.png)