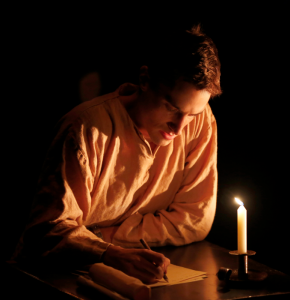

Jeff Britting, a composer and curator of the Ayn Rand Archives, has adapted Ayn Rand’s novella Anthem as stage play, which will be presented in New York City by the Austin Shakespeare Theater Company. Under the artistic direction of Ann Ciccolella, the production was originally performed in Austin, Texas in 2011.

Jeff Britting, a composer and curator of the Ayn Rand Archives, has adapted Ayn Rand’s novella Anthem as stage play, which will be presented in New York City by the Austin Shakespeare Theater Company. Under the artistic direction of Ann Ciccolella, the production was originally performed in Austin, Texas in 2011.

Rand wrote Anthem in the summer of 1937 during a break she took from writing her novel The Fountainhead. Anthem was published in England in 1938 and in America in 1946. To date, more than five million copies have sold.

Anthem's Off-Broadway staging coincides with the 75th anniversary of the novella’s publication. The play previews on September 25 at the Baryshnikov Arts Center's Jerome Robbins Theater (450 W, 37th Street), and it opens there on October 7, running through December 1.

Tickets, priced from $50 to $69, are available through www.AnthemThePlay.com or through Ovation Tickets at 866-811-4111.

Recently Mr. Britting joined me to discuss the play and the novella behind it. —Robert Begley

RB: Hi Jeff, thank you for taking time to discuss the coming Off-Broadway production of Anthem. I know readers of TOS Blog are interested to hear about the play and how it came about.

JB: Well, thank you. Glad to talk about the show.

The idea for Anthem the play began over twenty years ago. I was assisting in the production of another Ayn Rand work, Ideal. I moved to New York and began working on producing the play with my partners. And as a way to raise money to cover some venture debt, we decided to stage Anthem for a limited run at the Lex Theatre in Hollywood. The script was written and directed by Michael Paxton, who had directed the stage debut of Ideal. The run was successful. People responded to the material.

Meanwhile, the effort to raise money for an Off-Broadway production of Ideal continued. And my hope was to work on another iteration of the Anthem show. Eventually, the decision to work on it further fell into my lap as my partnership dissolved. And people wanted to move on with other projects. Alas, our effort to mount Ideal was not successful. However, each day in New York City, when I took the subway to work, I thought of Anthem. Sometimes, I stood at the front of the E train, watching the tunnel ahead, imagining what Anthem would look like on stage.

Jumping twenty or so years later, Ann Ciccolella, artistic director of Austin Shakespeare, approached me with the idea of staging Anthem. She had heard my film score to Ayn Rand: A Sense of Life. And she said, I want to do Anthem as an oratorio. Well, I figured what she meant was a straight play with music. So, we began from there. That was in 2008.

RB: Obviously, to have been motivated to adapt Anthem as a stage play you must have been deeply moved by the story. Would you say a few words about how Anthem the novella affected you?

JB: Sure. The work is a coming of age story. And most of Rand’s major characters are already formed at the start of the stories. But Equality 7-2521 was a young boy at the start of the show. And he becomes a man by the end of the show. And that transformation intrigued me.

RB: When did you decide to adapt Anthem into a play, and what were the major stages involved in developing it?

JB: First, I re-read the final, published work. Then I studied the passages cut from earlier versions of the novella. That was a key process. I always thought the story would work in three dimensions—and studying that cut material was very useful.

JB: First, I re-read the final, published work. Then I studied the passages cut from earlier versions of the novella. That was a key process. I always thought the story would work in three dimensions—and studying that cut material was very useful.

RB: In what ways is the script similar to the novel, and in what ways is it different?

JB: Well, there are two major differences. But these are differences within a certain context. The context was to keep the story arc intact and the ideas unaltered. But the goal was to translate the story into the theater. And this required a lot of editing. First, this was mainly cutting and condensing of the language in the book. But, as time went on, I realized that there were certain things in the book that had to step forward. Certain relationships had to be expanded. There is a great love story here between Equality and Liberty 5-3000, the young girl with whom he falls in love. And I found it very moving.

RB: Ayn Rand said that Anthem has a story but no plot. Do you agree with that? What is the difference between the two? And does the play have a plot?

JB: In the original novel, the story unfolds in the mind of a single character. And this young man, Equality, has a conflict with the world around him, which he recounts in a diary. At the moment he is set to grow as a person, the world around him says: You are not a person and there is nothing to grow into and become. He rebels. But his rebellion occurs largely in his mind. And while there is some envisioning of action—actually, much envisioning of action—there is not a definitive sequence of steps leading from the opening of the story to the discovering of the missing word, which, by the end of the book, the audience is well aware of and realizes is necessary. Maybe that’s why Ayn Rand called the work a poem. The theme and style is paramount—not the plot. Therefore, in the novella, as I understand it, we don’t observe Equality taking the final steps—and there is no sequence connecting the different parts of the story. But my idea for a stage play required that connection. Therefore, I had to add and re-organize things a bit. And this led to some discoveries, which are now a part of the fabric of this play. I won’t tell you what they are. That would ruin the suspense!

RB: Will the play be equally accessible to those who have read the book and those who have not? And how helpful would it be for attendees to read or re-read the novella before the show?

JB: I think a successful adaptation rises or falls on the work presented. If people need to read the book to understand the play, I didn’t complete the job. Was I successful? Well, you should be the judge of that. I certainly did my best to bring the story to life in another medium.

RB: Obviously the fully collectivist world of Anthem is quite different from our world today. But do you see parallels between the story and reality? If so, would you say a few words about them?

JB: I see a lot of parallels. Each day, I read the New York Times before leaving for the theater. And I have this standing assignment: connect the world of Anthem to the late breaking events of the day. Who can I marry? Where can I live? What kind of career can I achieve? These are just some of the stories breaking with Anthem-like implications. And the ideas crushing the individual are all around us, chipping away at us constantly.

RB: Not many script writers are also composers, and I suspect that your being both in this production has lent a special integrity to the play. What was it like to wear both of these crucial hats? And how would you describe the relationship between the script and the music in the play?

JB: That is my favorite topic. I really enjoy fusing text and music. Years ago, I learned of a musical technique present among non-musical plays in the late 19th century. The idea presaged film composition. The technique was to underscore the stage action—even dialogue—with music. I love film scores and opera, and I wanted to work in those forms. But theater was more accessible. And no one was doing this in the late 1970s, when I began working in the theater. So, I have written scores for thirteen plays, which are not musicals, but straight plays.

The result is that music becomes another prop helping to shape the actor’s performance. Music and text have several commonalities, and one is meter and rhythm. Both spoken word and music have certain regularities, and they can be sub-divided rhythmically. So, after I write a sequence, I just open the script and then sit at the piano keyboard and “play” the script. (And because I also draw and paint, sometimes I sketch out the action as well.)

Actually, one Anthem cue is a good example of the process. There is a four-minute sequence of music in Anthem, which underscores a prison sequence, and it lines up with five different, smaller scenes within one large scene. And after I wrote the larger scene, I composed the music. Basically, I composed the musical structure in one pass. The rest was editing and small adjustments. And when the play was read by actors with the music, the sequence timed-out perfectly. Now, not all cues are this easy, but you get the idea. The interplay between text and music makes Anthem a unified stage experience. Also, I collaborated with a brilliant young sound designer named Anthony Mattana, who enriched the sound of the total production with vocal effects, percussive and other sounds. He also mixed the sound effects and the music, using the theater’s first rate sound system to complement the theater’s acoustics. This completed my score.

Ayn Rand called her novella Anthem a “hymn to man’s ego.” My approach to Anthem the play was to provide the story a further dimension through music and sound. The work is now larger than a hymn. It’s really “spoken opera.”

RB: I understand that you are hosting “talk backs” in which certain audiences participate in discussing the play following the performance. How did this idea come about, and what do the discussions involve?

JB: After each performance of an Austin Shakespeare production, audiences are invited to stay for a ten-minute discussion of the work. And this tradition continues in our New York run. On Tuesday evenings, we have commentators joining us from across the thought spectrum—both left and right. After Saturday matinees, our talk backs will feature Ayn Rand scholars. But I stress this is an informal conversation. So far, we’ve had seven previews. And better than half the audience remains in their seats after performance. Typically, among the audience members joining the actors, the director, Ann Ciccolella and myself, about half of these theater goers have read the novel, and half have not read it. That is interesting.

RB: Where do you see the play going after the run in New York? Can we expect to see productions in other cities? And is there a way for people to help bring the play to a city near them?

JB: If Anthem finds an audience in New York City, my hope would be to see the play transferred to a commercial theatre for an open-ended run. Thereafter, I would love to see productions in other cities—and in other languages as well. But the best way to support this production is to see it yourself. And, if you like it, then speak out. Tell your friends. Let people know that Anthem the play exists!

RB: I have seen it and have told my friends, and I will see it several more times. Best success with the production, and thank you again for speaking with me.

Like this post? Join our mailing list to receive our weekly digest. And for in-depth commentary from an Objectivist perspective, subscribe to our quarterly journal, The Objective Standard.

Related:

- Transfiguring the Novel: The Literary Revolution in Atlas Shrugged

- “Best Friends” Ban in UK Schools Mirrors Ayn Rand’s Anthem

Images: www.AnthemThePlay.com

![[TEST] The Objective Standard](https://test.theobjectivestandard.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/logo.png)