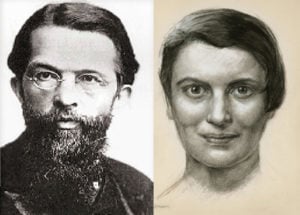

Image of Carl Menger: Wikimedia Commons

After TOS Blog published my article, “Ayn Rand Was Right: Cats Are Objectively Valuable,” several people challenged this idea on Facebook. They claimed that the theory of objective value I presented (based on Ayn Rand’s moral theory) somehow implies that Marx’s labor theory of value (i.e., that value is merely a function of labor) is true, that value can exist apart from a valuer, that an objectively valuable thing will have equal value to everyone, or the like. All such claims about objective value are in error.

Objective value does not mean that something has value apart from a valuer (the term for that theory is intrinsicism), nor does it mean that an objectively valuable thing is valuable to every person, nor does it mean that an objectively valuable thing has the same value to every person who values it.

What does objective value mean? Something is objectively valuable when the person seeking the object in question does so rationally, with the aim of genuinely advancing his life and happiness. Some but not all objective values are also universal values, meaning they are necessary to the life of every person. For example, food is objectively valuable to every person, because every person needs food in order to live. Wheat, by contrast, is objectively valuable only to those who eat it in order to further their lives and happiness; it is not objectively valuable to people who don’t care for wheat or to people with celiac disease (indeed, it is objectively harmful to the latter). Morphine is objectively valuable to a person using it for pain relief while recovering from invasive surgery; it is objectively harmful to a person who abuses the drug. We could multiply examples.

Whether something furthers one’s life or hinders it is a factual matter; it is not a matter of subjective opinion. That a human being needs food in order to live is not a matter of opinion; it is a matter of fact. That shooting huge quantities of morphine into your veins for “fun” is detrimental to your life is also a matter of fact. Even if a drug abuser pretends that his drugs further his life, in fact, they damage it. If someone subjectively feels that he can live on sunshine and rainbows rather than on food, and acts accordingly, we all know the inevitable outcome. Whether someone is alive or dead is a fact, not a subjective interpretation.

Why is the seemingly straightforward concept of objective value so difficult for many people—especially those with a background in economics—to understand? The answer is that many economists confuse agent-relative value—value in relation to some valuer—with morally subjective value.

Historically, various economists—including Adam Smith and Karl Marx—were stymied by the nature of value. Consider some common examples of the problem in question: Why do diamonds typically cost more than water, even though water is essential to life? Why do some things that are quick and easy to produce cost more or sell better than do other things that require great time and resources to produce? Why do some manual laborers earn more than some highly educated professors earn? How can people exchange two items and both be better off, given that the number and type of goods remain unchanged by the trade? Why is a person generally willing to pay less for an additional good than he was willing to spend on a previously obtained good of the same type?

In the late 1800s, several economists (including Carl Menger, founder of the Austrian school of economics) solved such problems with their “marginal revolution” (also sometimes called the “subjectivist revolution”). They pointed out that nothing is valuable in itself, apart from an actor. Something is a value because it is valued by a particular actor, and something’s value to a given person often changes based on various conditions. For example, if you have a lot of water and no diamonds, the value of an additional (“marginal”) unit of water to you is small, whereas the value of an additional diamond to you is potentially very great.

This is what economists mean when they discuss “subjective value” (when they are making sense): For anything to be a value it must be sought by a particular actor, and, in the realm of goods and services, the relative value of something to a given person can change based on the actor’s needs and goals, the quantity of the item already possessed, and other conditions.

This usage is in concert with Ayn Rand’s basic, generic view of value, that a value is that which one acts to gain and/or keep. However, this view ignores Rand’s further development based on this idea. Using this basic definition of value, Rand went on to observe and integrate many additional truths that led her to discover the objective standard of moral value, which is the requirements of man’s life. As Rand summarized, “All that which is proper to the life of a rational being is the good; all that which destroys it is the evil.”

Unfortunately, when some economists think of values as “subjective,” they assume that there is no objective standard for determining moral value; they assume that value is only a matter of personal opinion. In this view, there is no basic difference between someone “subjectively” valuing food in order to live and someone “subjectively” valuing morphine to feed a drug habit. But there is a huge difference: As a factual matter, in order to live, people need to eat food; they do not need to abuse drugs, and if they do abuse drugs, they harm their lives by doing so. Grasping this difference is crucial to understanding the objective theory of moral value. Economists who wish to understand these ideas more fully would do well to read Rand’s essays on the subject in The Virtue of Selfishness.

One need not reject the Marginal Revolution in economics in order to embrace the Objectivist Revolution in ethics, or vice versa; properly understood, the two are perfectly compatible and complementary. Properly understood, both are objectively true and objectively valuable.

Related:

![[TEST] The Objective Standard](https://test.theobjectivestandard.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/logo.png)