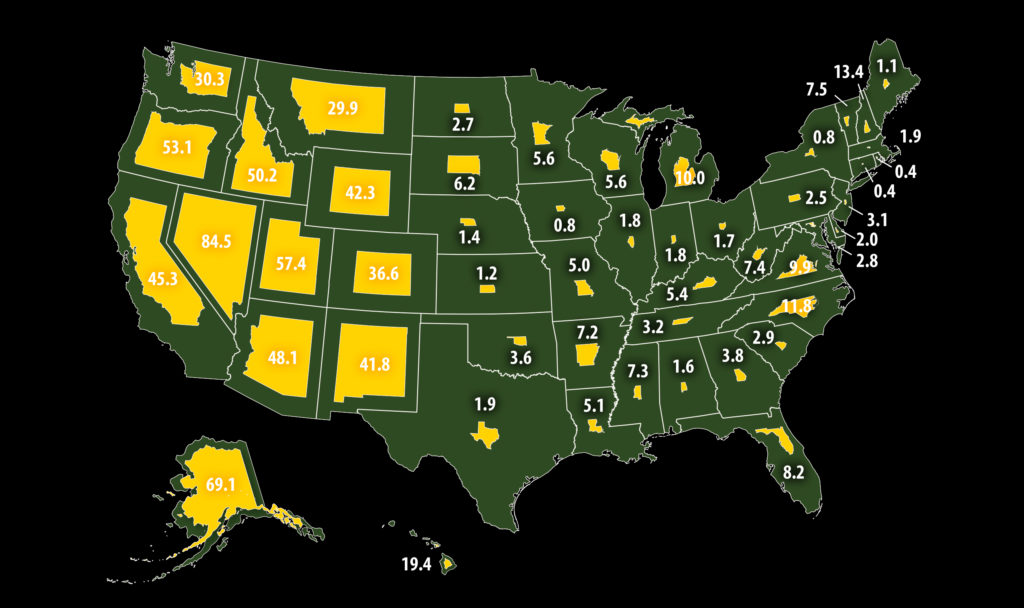

Today, in the “land of the free,” four federal agencies control about 610 million acres or roughly 28 percent of all American land. That’s more than all the land in Washington, Oregon, California, Idaho, Nevada, Utah, Arizona, Colorado, and New Mexico combined. State governments own more on top of this. These lands include state and national parks and forests, campgrounds, grasslands, seashores, and other areas known collectively as “public lands.”

Administering these lands costs taxpayers billions each year. But instead of life-enhancing benefits, we get underfunded, crumbling campgrounds and parks, many of which are being shut down. We get natural resources that are often harvested at a net loss or not at all. And we get vast tracts of other land barred from development that could otherwise help to grow communities, create jobs, boost economies, and improve people’s lives. In short, government agencies have turned a vast wealth of natural resources that could enrich our lives and our country into a collection jar that never stops going around.

Click To Tweet

We’re told that these public lands are necessary to ensure that America’s resources are used wisely, the thought being that if left to their own devices, people will shortsightedly wreck these resources. The Joni Mitchell song “Big Yellow Taxi” encapsulates this view, warning us about people who “paved paradise and put up a parking lot.” Those same people also

took all the trees

And put ’em in a tree museum

And they charged the people

A dollar and a half just to see ’em

Interestingly, these lyrics succinctly describe an incident from the 1850s involving a tree that was cut down on public domain land—an incident that lifelong National Park Service (NPS) employee William Everhart credits for giving the nascent American conservation movement “a sense of purpose.” He writes, “In California, frontier entrepreneurs in search of quick profits stripped the bark from a giant sequoia, exhibiting the reassembled specimen in eastern cities and, in 1854, at the Crystal Palace in London.” Everhart writes, “The incident, widely reported in the U.S. press, angered many people who damned the wanton destruction of a 3,000-year-old tree for a shilling a show.”1

Generally speaking, loggers in the 19th century who took advantage of public domain lands had no incentive to maintain the value and output of that land. In fact, because it was open to anyone, the only incentive was to beat the next guy to the punch. Reportedly, loggers were often enormously wasteful, felling far more trees than they could harvest and use. John Muir biographer Stephen Fox also claims that “In the Northwest, sheepmen and prospectors were burning off forest cover, regarding trees not even as board feet but as weeds.”2

Add to this the fact that by the latter half of the 19th century, Americans had largely tamed the continent. The national census of 1890 declared that “there can hardly be said to be a frontier line,” and influential Progressive historian Frederick Jackson Turner declared that the vanishing of the frontier “has closed the first period of American history.”3

To be sure, there was (and is) still plenty of uninhabited land, but Americans had finally found the bounds of their seemingly boundless continent and with it, the supposed bounds of its natural resources. In 1912, Theodore Roosevelt declared, “We believe that the remaining forests, coal and oil lands, water powers and other natural resources still in State or National control (except agricultural lands) are more likely to be wisely conserved and utilized for the general welfare if held in the public hands.”4

Calls to use natural resources more wisely were, to some extent, justified. So long as property remains a commons—outside the sphere of property rights—it truly is no man’s land, and anarchy reigns. All are basically free to use a commons however they please and take from it whatever they want. Because this problem is baked into how commons function, the phenomenon has its own name: the tragedy of the commons. The incentives governing how people treat a commons are exactly the opposite of those on private property. For instance, on his own property a rancher will alternate the grounds on which he pastures his herds so that they won’t eat the vegetation to the roots and destroy its ability to support further grazing. It’s his, so he has a reason to care about its long-term value.

On public land, it’s just the opposite; a rancher is incentivized to take advantage of the free resources before someone else does. He has no incentive to maintain or improve the land given that someone may use it in his stead. If he does the rational, responsible thing and regularly alternates pastures, another rancher may come along and allow his herd to graze these pastures to the roots. In a commons, the forward-thinking man can do nothing but plead with his fellow rancher not to do so.

Property rights solve this problem. They leave a man free to cultivate value and reap the rewards of that value. And they incentivize the rational, productive, life-enhancing use of resources.

Karabash, Russia

It is, therefore, unsurprising that communist countries have commonly been the most polluted places on the planet. Murray Feshbach and Alfred Friendly Jr. begin their book, Ecocide in the USSR: Health and Nature under Siege, with the prediction that “When historians finally conduct an autopsy on the Soviet Union and Soviet Communism, they may reach the verdict of death by ecocide,” meaning willful destruction of the environment. “No other great industrial civilization,” they continue, “so systematically and so long poisoned its land, air, water and people. None so loudly proclaiming its efforts to improve public health and protect nature so degraded both.”5

Given the situation in the American West during the 19th century, it’s conceivable that using the force of government to halt the tragedy of the commons on as-yet unowned land—as a stopgap until property rights accomplishing the same thing were established—might have been a sensible means of mitigating a temporary, practical problem.6 However, the political leaders spearheading the American conservation movement were not interested primarily in ensuring that land and resources were used wisely. They had deeper, more philosophic motives. When Roosevelt said, “Natural resources, whose conservation is necessary for the National welfare, should be owned or controlled by the Nation,” his primary goal was not ensuring that resources were used wisely.7 If politicians then or now were actually concerned with putting natural resources to their best use, they would advocate leaving the use of such resources to free markets and private businesses. In other words, they would advocate the protection of property rights. The protection of property rights leaves men and institutions free to use property however they choose and incentivizes productive use by ensuring that whatever a man earns is his to use or dispose of as he sees fit. In a system that protects property rights, a man is free to preserve natural beauty and places for rejuvenating recreation—on his property. On his property a man is free to harvest natural resources and incentivized to do so as efficiently as possible.

In truth, the primary driver for establishing the public lands we have today was a shift in American philosophy that accelerated between the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries.

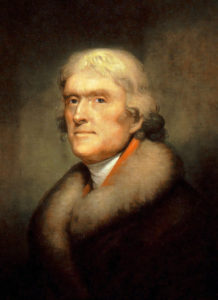

America was founded on the principle that every individual has the right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. (Slavery contradicted this basic principle, but it could not last in a country devoted to the ideas of the Declaration of Independence.) The United States was the first nation in history to recognize that the only legitimate purpose of government is protecting individual rights. In his inaugural address of 1801, President Thomas Jefferson declared that “the sum of good government” is “a wise and frugal government which shall restrain men from injuring one another, shall leave them otherwise free to regulate their own pursuits of industry and improvement, and shall not take from the mouth of labor the bread it has earned.”8

Individual rights codified in law the idea that the individual’s life is his own to live however he pleases—so long as he does not violate the same rights of others. This idea is the core of the uniquely American philosophy of individualism, which holds that a man should be free to rise as high as his ambition will take him, and that his mind and effort are what matter, not his position at birth. Individualism holds that men have neither a duty to serve any master, nor a right to exact servitude from others. A man is not the property of kings, of bureaucrats, or of his fellow men, who may dispose at will of his effort or the products thereof. Instead, “Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.” And those powers, in order to be just, must be strictly delimited to the protection of rights.

What sort of land policy is consistent with the individualist view of rights and of the role of government? Historian Paul Gates writes,

The preponderant, almost the universal view of Americans until near the end of the nineteenth century was that the government should get out of the land business as rapidly as possible by selling or giving to settlers, donating for worthy purposes and ceding the lands to the states which should in turn pass them swiftly into private hands.9

In line with the view that the government ought to “get out of the land business as rapidly as possible,” the U.S. government frequently lowered land prices. In 1862, President Abraham Lincoln signed the Homestead Act, which enabled any adult who had never taken up arms against the United States (including women and blacks) to apply for and earn land by “improving” it, typically by establishing a farm.10 Although the Homestead Act had its flaws, the principle underlying it was sound: Settlers would cultivate the land, increase its value, and advance their own prosperity—and, by extension, the country’s. The act was followed by a series of amendments that increased the size of land grants and by related laws that aimed at making it easier for settlers to attain land for other purposes.11 Thus, about 270 million acres, or roughly 10 percent of the United States, was granted to American settlers.

However, alongside American individualism grew a competing philosophy, imported from the old world. Its advocates agreed that government power derives from the people. But the will of the people, they held, is absolute; “just powers” are whatever powers the majority of people consent to. If the majority of people want to protect individual rights, the government must do so. If the majority of people want to infringe the rights of some individuals, their will be done. The majority, the people, the collective, should have absolute power over the individual—who has no rights to the contrary. The collective—or its self-proclaimed representatives in government—should decide on and enforce whatever it takes to be its “public good.” Because this philosophy enshrines the will of the collective over the rights of the individual, it became known as collectivism.

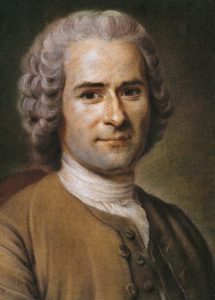

By contrast to Jefferson’s vision of the sum of good government, Collectivist spokesman Jean-Jacques Rousseau held that “legislation is at the highest possible point of perfection” when “each citizen is nothing and can do nothing without the rest, and the resources acquired by the whole are equal or superior to the aggregate of the resources of all the individuals.” To achieve such a goal, Rousseau acknowledged that ministers and bureaucrats must labor at “changing human nature, [and] transforming each individual, who is by himself a complete and solitary whole, into part of a greater whole from which he in a manner receives his life and being.” Moreover, “He must, in a word, take away from man his own resources and give him instead new ones alien to him, and incapable of being made use of without the help of other men.”12

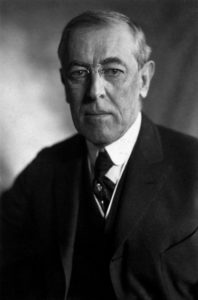

Collectivism was the essence of the American “Progressive” movement, so called because its adherents aimed to progress beyond the individual rights of the Declaration and the limited government of the Constitution. As Woodrow Wilson put it:

The Constitution was founded on the law of gravitation. The government was to exist and move by virtue of “checks and balances.” The trouble with the theory is that government is not a machine, but a living thing. It falls, not under the theory of the universe, but under the theory of organic life. It is accountable to Darwin, not to Newton.13

Toward what end should the government evolve? Theodore Roosevelt declared, “We of to-day who stand for the Progressive movement here in the United States are not wedded to any particular kind of machinery, save solely as the means to the end desired. Our aim is to secure the real and not the nominal rule of the people.”14 That is, the Progressives aimed to replace the rights-protecting republic of the founders with an unlimited democracy—to replace the uniquely American philosophy of individualism with collectivism.

The American conservation movement—which claimed that the “public good” required putting millions of acres of American land under permanent government control—was of a piece with the broader Progressive movement. Fox writes, “As one of these progressive reforms, conservation moved in lockstep with the larger context of the time.”15

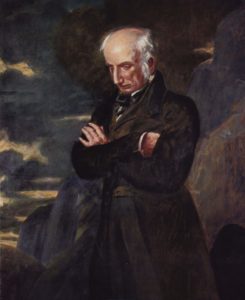

The conservation movement adopted another tenet along with the Progressive movement’s collectivism, which likewise came from Rousseau. According to Rousseau, “Men are not made to be crowded together in ant-hills, but scattered over the earth to till it. The more they are massed together, the more corrupt they become. Disease and vice are the sure results of over-crowded cities.”16 Rousseau held that civilization was a sin from which nature alone could protect men: “Men are devoured by our towns. In a few generations the race dies out or becomes degenerate; it needs renewal, and it is always renewed from the country.” The seed of Rousseau’s back-to-nature philosophy grew to become the 19th-century Romantic movement. One of the leaders of this movement, William Wordsworth, wrote:

Let Nature be your teacher. . . .

One impulse from a vernal wood

May teach you more of man,

Of moral evil and of good,

Than all the sages can.

Sweet is the lore which Nature brings;

Our meddling intellect

Mis-shapes the beauteous forms of things:—

We murder to dissect.

Enough of Science and of Art;

Close up those barren leaves;

Come forth, and bring with you a heart

That watches and receives.17

This philosophy was picked up and transmitted to a new American audience by transcendentalists Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson, and it became the foundation for the burgeoning conservation movement. Fox writes of the movement, “Antimodern and skeptical of technological progress, it invoked a vision of pre-industrial community when people lived closer to the land and the natural rhythms of life.”18

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Romanticism fueled the fire of the conservation movement—a movement that had an increasingly powerful weapon at its disposal: the Progressives’ collectivist, bureaucratic machinery. The result? According to Gates, “The democratic individualism of the nineteenth century was being replaced by the democratic collectivism of the twentieth century. The history of American land policy reflects this transformation.”19

That history also reveals a slippery slope of legal precedents that set the stage for Progressives to begin nationalizing American land on a massive scale. The first steps down that slope were taken during the administrations of Presidents Abraham Lincoln and Ulysses S. Grant. In 1864, a congressman suggested that the federal government cede land in Yosemite Valley to the state of California “for public use, resort and recreation.” Everhart recounts:

The congressman who introduced the legislation explained only that “certain gentlemen in California, gentlemen of fortune, of taste, and of refinement” had suggested the measure. There being no one so churlish as to demand further details, the measure passed Congress without debate. Grants to the states from the federal government were not uncommon at the time, although the stipulation that the lands “shall be held for public use, resort and recreation” was significant and unprecedented.20

This was the first major trial balloon for the conservation movement, and it could not have been more telling. Lincoln signed the bill, and the precedent was set. A mere sixty-three years after Jefferson’s first inaugural, the nation’s leaders accepted without debate the idea that if a large enough—or affluent enough—group demanded it, the government could hold land for “the public” in perpetuity. Thus, they abandoned the nearly universal view “that the government should get out of the land business as rapidly as possible.”

Eight years later, in March 1872, under similar circumstances, President Ulysses S. Grant signed the bill establishing Yellowstone National Park, claiming two million acres “as a public park or pleasuring ground for the benefit and enjoyment of the people.” On this, Everhart reflected:

Reserving so large an expanse of land—larger than the two eastern states of Rhode Island and Delaware combined—with all of its potential wealth of water power, timber, and grazing lands barred from private use was so dramatic a departure from the public land policy of Congress that in retrospect it almost seems to smack of the miraculous. The explanation is probably not all that complex. The public domain still seemed endless, no commercial interests were immediately threatened, and creating the preserve cost the government nothing.21

Yellowstone was supposed to cost the government nothing because it put “in charge” an unpaid civilian superintendent. But the superintendent had no genuine authority. He did not own the land and thus had no property right to it. Nor did Congress grant him any specific legal authority to prohibit certain activities. Historian H. Duane Hampton writes:

the Act [establishing Yellowstone National Park] provided no specific laws for the government of the region; it neither specified offenses nor provided punishment or legal machinery for the enforcement of such rules as might be promulgated by the Secretary of the Interior. No appropriation was made for administering the Park, for constructing roads, or for protecting the Park from vandalism. One result of this parsimony was that the first Superintendent was forced to serve without remuneration and, except for his infrequent visits, the Park was entirely without supervision.22

What this amounted to was an “attempt” to halt the tragedy of the commons by establishing official commons in perpetuity. If this sounds akin to fighting fire with fire, it’s because that’s what it was. Poachers and “vandals” continued to be a problem in the newly formed park. In order to enforce its claims, the government had to put its money where its mouth was. In 1886, the Secretary of the Interior consulted with the Secretary of War.23 On August 20, 1886, the United States Army took charge of Yellowstone—and held it for the next thirty years. Of course, this had to be paid for—by tax dollars. Thus, another precedent was set; not only could the government claim land in perpetuity in the name of the “public interest,” it could also “take from the mouth of labor the bread it has earned” in order to pay for it.

With these precedents, the conservation movement was prepared for its first real battle. Thus far, the government had only created parks from the public domain. It had yet to test whether the “public good” could be used to abrogate property rights, whether the collective could take an individual’s land. That experiment would take place during the campaign to establish a reservation at Niagara Falls.

Since the state of New York had auctioned the lands surrounding the falls in 1805, the area had been rapidly industrialized.24 Early entrepreneurs recognized the enormous potential of harnessing the power of the falls. Others saw opportunities in catering to the massive crowds of tourists that the falls attracted. As early as 1838, Niagara lured twenty thousand visitors per year; by 1850, it was fifty thousand.

In 1855, John A. Roebling—who later designed the world-famous Brooklyn Bridge—built the Niagara Railway Suspension Bridge. In 1881, the Niagara Falls Hydraulic Power and Manufacturing Company built the region’s first hydroelectric station, and as the New York Power Authority reports:

The availability of power resulted in the proliferation of industry along the river, including: the Gaskill Flouring Mill (1875), Pittsburgh Reduction Company (1895, later known as the Aluminum Corporation of America, or ALCOA), Niagara Falls Hydrologic and Manufacturing Power Company (1896, later known as the Schoellkopf Power Station), and the Niagara Mohawk Power Company (1953).25

These industries brought people, wealth, and massive increases in standards of living to the area.

But conservationists throughout the country and the world were upset about what Niagara’s incredible industrial flourishing had done to the view of the falls. English writer H. G. Wells later wrote that Niagara’s “spectacular effect, its magnificent and humbling size and splendor, were long-since destroyed beyond recovery by the hotels, the factories, the power-houses, the bridges and tramways and hoardings that rose about it.”26 Given that the lands surrounding the falls were privately owned, there was little that conservationists could do. When a prominent conservationist asked ex-Governor Alonzo Cornell, “‘Governor, you surely do not think it right that the Falls of Niagara should be fenced in, as they are at present, and the public charged to look at them?’ he answered, ‘Of course I do. They are a luxury and why should not the public pay to see them?’”27

But times—and more importantly, ideas—were changing. In 1879, New York Governor Lucius Robinson suggested that a committee investigate “preservation of the scenery of the Falls of Niagara,” and the state legislature appointed a surveyor along with Frederick Law Olmsted—a noted conservationist and landscape architect who also served on the Yosemite Board of Commissioners—to assess the situation and report back. The following year, their report nonchalantly advised “the extinguishment of the private titles to certain lands immediately adjacent to the falls, which the State should acquire by purchase and hold in trust for the people forever.”28 Their plan for establishing a reservation at Niagara Falls required appropriating $1.5 million from taxpayers and using eminent domain to seize private property. Although the plan’s advocates claimed to be acting “for the people,” the reservation bill was widely opposed. However, few (if any) denounced it as a violation of rights. Instead, most critics focused on the price.

Landowners protested that the appraisal prices for their land was far too low because the appraisers failed to adequately account for the unique value of access to the river’s natural water power. “They were especially strenuous,” wrote an advocate of the plan, “concerning their claims for damages as riparian owners, claiming to own the fulum aquae, or thread of the stream, and consequently the water power of the river. This claim the appraisers excluded, and the appeals followed.”29

On the other side of the deed, many considered the price too high. Thomas Welch, who helped spearhead the conservationists’ efforts at Niagara, wrote, “This proposition was not looked upon with favor by the State officers who did not wish to quit office with a depleted treasury, such as this measure would entail.” A deputy attorney general held that “the proposal to withdraw one and a half million of dollars from the State Treasury, for such a purpose, would never be sanctioned.”

“In many counties of the State,” Welch reported, “granges and other organizations of farming people had adopted resolutions denouncing the measure, and in consequence the opposition to the measure was especially strong among the rural members.”30 Welch also recounted that, “John I. Platt of the Poughkeepsie Eagle wrote ‘We regard this Niagara Falls scheme as one of the most unnecessary and unjustifiable raids upon the State Treasury ever attempted, consequently we shall not write any letters in its favor, but shall oppose it in any way.’”31 Also, “John E. Cady of Tompkins said that, excepting some professors in Cornell University, 20 persons could not be found in his county who favored the bill.”32

Some were sympathetic to the project. One enthusiastic supporter asked his congressmen “to use voice and vote to preserve the scenery of the Falls of Niagara by proper legislation and make its beauties free to all, like the sun in heaven.”33 Another wrote, “I am heartily and earnestly in favor of the passage of this bill, even if the State has to pay largely for it. It is one opportunity of a lifetime. [sic] Am willing to pay my portion of the tax. Go ahead!”34

Support from another set of people was particularly important. As was generally true of the Progressive movement, this project benefited from the watchful guidance of powerful politicians and bureaucrats. One assemblyman responded to a request for his support thus:

You can have no idea of the amount of pressure which is being brought to bear on me in opposition to this bill. Some of Rochester’s most prominent citizens have been here to advise me to oppose it, and I am daily in receipt of letters asking me to take that course, and threatening me with political oblivion should I vote for the bill. . . . As I am not cowardly enough to dodge the question I will endeavor to do that which will be pleasing to my friends and vote for it [emphasis added].35

Another advocate was Attorney General J. B. Harrison, who assisted in developing a legal strategy to establish the park, as did Ansley Wilcox, a high-profile lawyer and close associate of Theodore Roosevelt. First, the plan was altered to bring the price down to $1,000,000—the legal limit set by the state constitution. Still, because of the cost, they feared that the bill would be struck down as unconstitutional. So they structured it in sections, which would permit congress to scrap the appropriation section without dooming the entire bill, in which case funding would have to be found elsewhere. In the words of Wilcox, “This subject has been fully discussed by Mr. Rogers, Mr. Dorsheimer and myself and we all agree that such a provision would be very dangerous. If anyone raised the point I think it would certainly be held to be unconstitutional.” However, “if the first two sections are left just as they are, making an absolute appropriation and giving absolute directions for payment, then the addition of an unconstitutional section providing for the issue of $1,000,000 bonds would not invalidate the two preceding sections.”36

Another of the plan’s advocates, state senator J. Hampden Robb, “was a leading member of the Niagara Falls Association . . . and a watchful observer” of the bill once it reached New York’s Congress. In 1885, the bill passed through the state legislature—appropriations and all—finally landing on the desk of Governor David Hill.

But even in victory, the reservation bill had to be propped up on legal stilts. The governor’s counsel, Judge Samuel Hand, “expressed an opinion to the Governor that he had grave doubts of the constitutionality of any bill calling for an issue of the bonds of the State for one million of dollars (the limit of the Constitution), for any purpose excepting a great public emergency.” When Welch confronted him, Judge Hand

said that he did not have the Reservation bill in mind when he gave his opinion to the Governor and that he was heartily in favor of it, and added that in a sense it might be considered a great public emergency, as the opportunity to establish the Reservation might not occur again. When asked if he would so modify his opinion expressed to the Governor he at length consented, and wrote a letter to that effect, and gave it to the writer to hand to the Governor. When Governor Hill read the letter he threw it down upon his desk with a gesture of impatience, and said “That’s just the way with the damned lawyers; they will give you an opinion on one side of a question today, and on the other side tomorrow.”37

Hill, who oscillated between vetoing the bill and letting it expire, signed it at the eleventh hour. Progressive politicians averted the “great public emergency,” disregarding the wishes of a significant portion of the public. The state took $1 million from taxpayers and hundreds of acres of land from its owners. Thus, the conservation movement won an emboldening victory over individual rights. Most telling, the Progressives had done all of this while evoking only a few weak, local cries of outrage. No one rose to point out that the New York government had trampled individual rights—that they had made property rights subject to the will of “the collective” or its self-proclaimed representatives.

The stage was thereby set for the next showdown, the next important development of the American conservation movement. It came five years later with efforts to make Yosemite the country’s second national park. Like Yellowstone, Yosemite had proved unmanageable under a scheme of civilian stewardship, which placed civilians “in charge” but gave them little authority to support that responsibility. John Muir, who later founded the Sierra Club, long pined for the federal government to control his favorite scenic areas, and he led the Yosemite campaign. Of those “who are spreading black death in the fairest woods God ever made,” he said, “let the government up and at ’em.”38 Ominously, in 1890, those seizing tax dollars and property also managed to seize the moral high ground. As one writer puts it,

The campaign for Yosemite set a pattern to be repeated many times in future public quarrels over the environment. On one side: its defenders, spearheaded by amateurs with no economic stake in the outcome, who took time from other jobs to volunteer time and money for the good fight. On the other side: the enemy, usually joining the struggle because of their jobs, with a direct economic or professional interest in the matter and (therefore) selfish motives. Politics seldom lends itself to such simple morality plays. But environmental issues have usually come down to a stark alignment of white hats and black hats.39

No one rose to point out that the hats were on the wrong heads or that, by establishing the park, the government would again be stepping outside its proper role of protecting rights—that it would, in fact, be violating rights. Predictably, in 1890, Yosemite was established as the country’s second national park.

As they took power, Progressive politicians moved with greater assurance and rapidity. Their confidence was demonstrated the following year when they passed a law that would, for a time, spare them the trouble even of acting out “such simple morality plays.” As Everhart writes:

The Forestry Reserve Act of 1891, consisting of only a few lines added to an omnibus public land bill, was one of the most far-reaching conservation measures ever enacted. It gave the president unilateral authority to establish national forests from the public domain; no congressional approval was required. . . . Before this executive authority was abolished in 1907, four presidents set aside 175 million acres of national forest lands.40

Thus, these politicians expanded the practice of collectivizing land beyond parks for recreation. “For continued and permanent public ownership of the reserves and public controls,” Gates writes, “there was no great support in the Senate, perhaps not in the House.” However, “By a series of fortuitous circumstances, including adroit leadership, forest reserves were authorized almost a generation before Congress was ‘fully converted to the principle’ underlying them.”41 What did that “adroit” leadership consist of? The conservationist and editor of Forest and Stream magazine, George Bird Grinnell, gave at least a partial answer when he reflected that “Probably no one who read over the bill before it became law understood what the section [giving the president unilateral authority to create forest reserves] meant.”42 Considering the surreptitious tactics of Progressive politicians, Everhart makes an observation about national parks, which applies equally to national forests: “Although there is no question that parks, properly understood, were established for the people, whether they were established by the people is another matter altogether.”43

Though it was an act of blatant subterfuge and another blow to the country’s founding principles, the Forestry Reserve Act was not then questioned or overturned. Shyster politicians acted behind closed doors, invoking the “public interest,” while trampling the rights of the individuals who comprised the public—without fear of moral or intellectual opposition. The Progressive era was coming into full bloom, and the government was rapidly shifting from one that respected and protected individual rights to one that subordinated all rights to the “liberty of the community.”44 The Forestry Reserve Act of 1891 was merely one of many outward signs of the shift from a government of individualism to one of collectivism. Gates writes:

The new forest policies involved a sharp break with the philosophy on which American land policy had thus far rested, that is that the government should not be in the business of purveying land any longer than necessary, that it should provide for the easy and early transfer of the public lands to private ownership, that it should not retain from private ownership any part thereof. . . . Neither was this stride toward collectivism the work of single taxers, socialists, or other doctrinaire radicals. True, German intellectuals who were familiar with state forestry in Europe had contributed to the movement but the pressure for the change came out of American experience.45

Despite this last claim, Gates admits that the “American experience” of most Western pioneers and states was one of increasing frustration in the face of the encroaching federal government.

These states opposed withdrawals and in line with past policy wished the public lands transferred to private hands without reservations. Withdrawing of lands from entry, permanent retention of the land by the Federal government, restrictions on land use, leasing and stumpage fees, the forest purchase program all were condemned as the exercise of unconstitutional power, encroachments upon the rights of states and of individuals, and filching of public funds.46

But explicit condemnations, which came from frontiersman and a few middling politicians, were rare and scarcely ever defended rights on principle. America’s leadership, her “intellectuals,” were increasingly hostile toward the country’s legacy of manifest destiny and individual rights. For instance, in 1893, two years after the Forestry Reserve Act was passed, Frederick Jackson Turner argued before the country’s most prestigious historical society, the American Historical Association, that

the democracy born of free land, strong in selfishness and individualism, intolerant of administrative experience and education, and pressing individual liberty beyond its proper bounds, has its dangers as well as its benefits. Individualism in America has allowed a laxity in regard to governmental affairs which has rendered possible the spoils system and all the manifest evils that follow from the lack of a highly developed civic spirit.47

Then, in 1901, Progressives gained the presidency. In his first annual message to Congress, President Theodore Roosevelt declared that “forest reserves should be set apart forever for the use and benefit of our people as a whole and not sacrificed to the shortsighted greed of a few.”48 Capitalizing on the tragedy of the commons, he argued that in order to protect the forests for “the people,” the government had to protect them from the people. The man for this job was Gifford Pinchot, an American groomed in Europe at the French National School of Forestry who would become Roosevelt’s trusted advisor. Gates writes approvingly:

Roosevelt, under the tutelage and influence of Gifford Pinchot, espoused and pushed vigorously a program of public land reservation and utilization that makes his administration stand out with that of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s as the greatest and most forward looking in matters of planning and conservation. Approximately 100 million acres of public lands were placed under national forest status in Theodore Roosevelt’s administration.49

Pinchot echoed and amplified Roosevelt’s calls for collectivized land and resource management. He argued that government should manage large tracts of land to ensure that they served “the greatest good of the greatest number in the long run.”50 He lobbied for the creation of the United States Forest Service (USFS) and, in 1905, was appointed its first director. “No other agency in the growing federal bureaucracy,” writes Gates, “was so advanced in its planning, as collectivist in its thought, as free from doctrinaire conservatives and at the same time free from utopian radicalism as was the National Forest Service under Pinchot, Graves, and successors.”51

A few quavering voices offered timid resistance against the swelling collectivist tide. Colorado Senator Henry Teller Moore meekly offered that “My own idea is that what is everybody’s is nobody’s. . . . For any permanent business . . . you have got to have some form of possessory right,” adding “We cannot remain barbarians to save timber.” Colorado Representative Herschel Hogg resorted to mockery, calling Progressive conservationists a bunch of “goggle-eyed, bandy-legged dudes from the East and sad-eyed, absent-minded professors and bugologists.” One man (quoted but unnamed in Michael McGerr’s history, A Fierce Discontent) did better, saying, “[If] you had breathed the spirit of liberty for thirty years on Colorado mountain tops, you would understand and hate ‘Pinchotism’ as I do. . . . It is diametrically opposed to all true Americanism.”52 Other voices rose in protest, but none reminded the American public of the proper role of government, explicitly denounced the attack on individual rights, or retook the moral high ground.

Instead, debate centered on what should be done with the land once seized. Ostensibly, Muir and the movement he represented disagreed with Pinchot and his supporters. Pinchot was a committed utilitarian and paternalist who held that natural resources should be protected from men for their own benefit. By contrast, Muir was a link between the 19th-century Romantic movement and the “Deep Ecology” movement of the 1970s. He held that the government should not manage lands for the benefit or enjoyment of man: “The dogma ‘that the world was made especially for the uses of men,’” he insisted was an “enormous conceit.”53 In Muir’s view, nature should be preserved, not for humans’ sake, but for its own sake—even at the expense of man’s benefit and enjoyment.

Though in one flight of fancy Muir called for the government to enforce “compulsory recreation,” he was often disdainful even of those who made the arduous journey to enjoy his “holy Yosemite.” One season, he groaned:

All sorts of human stuff is being poured into our valley this year, and the blank fleshly apathy with which most of it comes in contact with the rock and water spirits of the place is most amazing. . . . They climb sprawlingly to their saddles like overgrown frogs pulling themselves up a stream-bank through the bent sedges, ride up the valley with about as much emotion as the horses they ride upon . . . and long for the safety and flatness of their proper homes.54

In Muir’s view, only members of an elite caste—unencumbered by the selfish acquisitiveness of modern society—were capable of appreciating nature’s “inherent” value. He wrote to Ralph Waldo Emerson:

Do not thus drift away with the mob while the spirits of these rocks and waters hail you after long waiting as their kinsman and persuade you to closer communion. . . . I invite you to join me in a month’s worship with Nature in the high temples of the great Sierra Crown beyond our holy Yosemite. It will cost you nothing save the time and very little of that for you will be mostly in eternity. . . . In the name of a hundred cascades that barbarous visitors never see . . . in the name of all the spirit creatures of these rocks and of this whole spiritual atmosphere Do not leave us now.55

Pinchot and Muir had different reasons for wanting to “protect” hundreds of millions of acres of American land from Americans—but both agreed that the land must be protected from them. To ensure that this happened, they held that in accord with the broader Progressive creed, the government must “progress” beyond the limits set by America’s founders. John Adams understood that protecting individual rights required “a government of laws, not of men.” Progressives understood that implementing the “public interest” required empowering those with “administrative experience and education” to decide what the “public interest” consists of—and to execute it unilaterally.

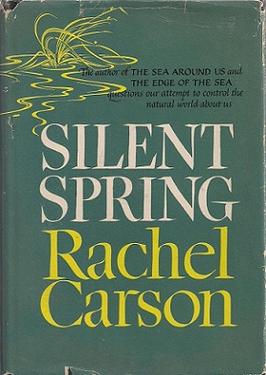

The battle between the ideals of Pinchot and those of Muir still rages, and Muir’s heirs—the viler of these combatants—are winning. Rachel Carson picked up Muir’s torch and galvanized the anti-industrial, anti-man philosophy with her 1962 book, Silent Spring, which Norwegian “philosopher” Arne Næss credits for inspiring his “Deep Ecology” movement, which in turn gave rise to the “green movement,” “ecopolitics,” and “environmentalism.” Nevertheless, both sides—empowered by collectivism—have scored tremendous victories over individual rights.

Today, the USFS controls about 193 million acres—more than the total area of Texas and South Carolina combined—including so many different areas of so many different types that identifying and categorizing them requires a 265-page document.56 And the NPS controls 417 park sites spanning across more than eighty-four million acres—totaling roughly twice the size of Georgia—and extending into the U.S. territories, including parks in Puerto Rico, the Virgin Islands, American Samoa, and Guam.57

We can judge the claim that “public lands are necessary in order to ensure that resources are used wisely” by examining the practices of government land agencies and the dilapidated status of their holdings today. The national parks, which many call “America’s national treasure,” have massive maintenance backlogs, and they’re steadily being run into the ground. In July 2018, Holly Fretwell of the Property and Environmental Research Center testified before a senate subcommittee saying,

The effects of the backlog show up throughout the National Park System in the form of dilapidated visitor centers, deteriorating wastewater systems, and crumbling roads, bridges, and trails. Two-fifths of all paved roads in national parks are rated in “fair” or “poor condition.” Dozens of bridges are considered “structurally deficient” and in need of rehabilitation or reconstruction. And thousands of miles of trails are in “poor” or “seriously deficient” condition.58

Whatever the USFS is doing, no one can claim that it is using resources wisely. Although the agency controls 193 million acres of resource-rich land, it continues to cost taxpayers several billion dollars each year.59 Environmental researcher John Baden writes, “Bureaucracies, regardless of their mission, eventually tend to be run for the people in them, and the clientele they benefit. The Forest Service is no exception.”60 Also, given that tax appropriations to the USFS are tied primarily to timber sales, it’s unsurprising that the agency engages in what some call “ecologically destructive timber sales.” The federal government incentivizes the USFS to harvest as much as possible with little consideration of other factors.

In Jefferson’s words, the taxes forced from people to fund these agencies “take from the mouth of labor the bread it has earned.” In line with Rousseau’s vision, they “take away from man his own resources and give him instead new ones alien to him, and incapable of being made use of without the help of other men.” Astutely summarizing the development of America’s land policy, Gates writes, “Individualism and laissez faire were thus given body blows in the citadel of capitalism.”61

Some call the country’s national parks “America’s best idea.” In truth, the idea of public lands of any type is not American at all. Public lands are essentially collectivistic and thus antithetical to what is truly America’s best idea—and its fundamental principle: individual rights. If we wish to preserve that idea, we must retake the moral high ground and work to privatize all public lands.

Click To Tweet

You might also like

Endnotes

1. William C. Everhart, The National Park Service (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1983), 5.

2. Stephen Fox, John Muir and His Legacy: The American Conservation Movement (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1981), 114.

3. Frederick Jackson Turner, “The Significance of the Frontier in American History,” in American Progressivism: A Reader, edited by Ronald J. Pestritto and William J. Atto (New York: Lexington Books, 2008), 67, 86.

4. Theodore Roosevelt, “Progressive Platform of 1912,” in American Progressivism, 281.

5. Murray Feshbach and Alfred Friendly Jr., Ecocide in the USSR: Health and Nature under Siege (New York: Basic Books, 1993), 1, available at https://www.questia.com/read/99860797/ecocide-in-the-ussr-health-and-nature-under-siege.

6. I refer to public domain land that is not managed or regulated as as-yet unowned land. I do so because nothing and no one constrains its usage: not property rights, not government functions or decrees, and not bureaucrats. It is unowned because what is everybody’s is nobody’s.

7. Roosevelt, “Progressive Platform of 1912,” in American Progressivism, 282.

8. Thomas Jefferson, Inaugural Address of March 4, 1801, quoted in Noble E. Cunningham, The Inaugural Addresses of President Thomas Jefferson 1801 and 1805 (Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 2005), 5.

9. Paul Gates, The Jeffersonian Dream: Studies in the History of American Land Policy and Development (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1996), 109.

10. Successfully establishing a homestead under the act was no easy feat. Settlers had to show proof of having improved their land claims, they had to live on the land for five years, and they had to complete the process within seven years. Gates reports that “For the country as a whole, slightly less than 50 per cent of the original homesteads were carried to patent.” See Paul Gates, The Jeffersonian Dream, “The Homestead Act: Free Land Policy in Operation, 1862–1935,” 48.

11. These included the Southern Homestead Act of 1866, the Timber Culture Act of 1873, the Kinkaid Amendment of 1904, the Enlarged Homestead Act of 1909, and the Stock-Raising Homestead Act of 1916. See Paul Gates, Jeffersonian Dream, “The Homestead Act: Free Land Policy in Operation, 1862–1935.”

12. Jean-Jacques Rousseau, The Works of Jean-Jacques Rousseau: The Social Contract, Confessions, Emile, and Other Essays (Halcyon Press Ltd, Kindle Edition), loc. 432–44.

13. Woodrow Wilson, “What is Progress?,” in American Progressivism, 50.

14. Theodore Roosevelt, “Who Is a Progressive?,” in American Progressivism, 36.

15. Fox, John Muir and His Legacy, 108.

16. Rousseau, The Works of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, loc.12520–12525.

17. William Wordsworth, “The Tables Turned,” Poetry Foundation, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/45557/the-tables-turned (accessed July 13, 2018).

18. Fox, John Muir and His Legacy, 108.

19. Gates, Jeffersonian Dream, 98.

20. Everhart,National Park Service, 6–7.

21. Everhart,National Park Service, 8–9.

22. H. Duane Hampton, “The Nation's First National Park,” How the U.S. Cavalry Saved Our National Parks (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1971), https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/hampton/chap2.htm.

23. “Birth of a National Park,” National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/yell/learn/historyculture/yellowstoneestablishment.htm (accessed November 9, 2018).

24. “Niagara Falls: Then and Now,” New York Power Authority, http://niagara.nypa.gov/RelicensingGreenwayFunds/EcologicalGreenway/NGR_Part01.pdf (accessed August 5, 2018).

25. “Niagara Falls” New York Power Authority.

26. Fox, John Muir and His Legacy, 108. Although Wells wrote this after Niagara Falls was made a park, he captures the general stance of conservationists before the park was established.

27. Thomas V. Welch, How Niagara Was Made Free: The Passage of the Niagara Reservation Act of 1885 (Buffalo: Press Union and Times, 1903), 22.

28. Welch, How Niagara Was Made Free, 3–10.

29. Welch, How Niagara Was Made Free, 24.

30. Welch, How Niagara Was Made Free, 3–10.

31. Welch, How Niagara Was Made Free, 13.

32. Welch, How Niagara Was Made Free, 10.

33. Welch, How Niagara Was Made Free, 15.

34. Welch, How Niagara Was Made Free, 14.

35. Welch, How Niagara Was Made Free, 10.

36. Welch, How Niagara Was Made Free, 24.

37. Welch, How Niagara Was Made Free, 32–33.

38. Fox, John Muir and His Legacy, 114.

39. Fox, John Muir and His Legacy, 103.

40. Everhart, National Park Service, 10–11.

41. Gates, Jeffersonian Dream, 111.

42. Fox, John Muir and His Legacy, 110.

43. Robert Righter, “National Monuments to National Parks:

The Use of the Antiquities Act of 1906,” National Park Service: History E-Library, https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/hisnps/npshistory/righter.htm, (accessed June 20, 2018).

44. This was a phrase used by Progressive president Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

45. Gates, Jeffersonian Dream, 111.

46. Gates, Jeffersonian Dream, 113.

47. Turner, “The Significance of the Frontier in American History” in American Progressivism, 85–86.

48. Theodore Roosevelt, “First Annual Message: December 3, 1901,” The American Presidency Project, http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=29542 (accessed August 7, 2018).

49. Gates, Jeffersonian Dream, 112.

50. Fox, John Muir and His Legacy, 110–12.

51. Gates, Jeffersonian Dream, 112.

52. Michael McGerr, A Fierce Discontent: The Rise and Fall of the Progressive Movement in America (New York: Oxford University Press, 2003), 167–68.

53. Fox, John Muir and His Legacy, 59.

54. Fox, John Muir and His Legacy, 14.

55. Fox, John Muir and His Legacy, 5.

56. “Land Areas of the National Forest System,” United States Department of Agriculture: Forest Service, January 2012, https://www.fs.fed.us/land/staff/lar/LAR2011/LAR2011_Book_A5.pdf; The USFS’s 193 million acres equals about 781,043 km2. The total area of Texas is about 695,662 km2, and the total area of South Carolina is about 82,933 km2. Together they equal 778,595 km2, which is 2,448 km2 less than the total area controlled by the USFS. These numbers come from “List of U.S. States and Territories by Area,” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_U.S._states_and_territories_by_area (accessed November 13, 2018).

57. Rocío Lower, “How Many National Parks are There?” National Park Foundation, October 16, 2016, https://www.nationalparks.org/connect/blog/how-many-national-parks-are-there; In addition, the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) controls 248 million acres, an area the size of Egypt or about 10.5 times the size of New England, and the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) controls another 89 million acres—an area bigger than Germany and a little smaller than Montana.

58. Holly Fretwell, “Restoring Our National Parks,” July 11, 2018, The Property and Environmental Research Center, https://www.perc.org/2018/07/11/restoring-our-national-parks/.

59. The 2019 USFS budget is $4.7 billion. Also, over the last decade, the NPS has cost an average of $2.84 billion per year; President Donald Trump has proposed a $2.7 billion NPS budget for 2019. The 2019 BLM budget is $930 million. The 2019 USFWS budget is $2.8 billion.

60. John A. Baden and Andrew C. St. Lawrence, “A Century of Forest Service Ineptitude,” Foundation for Economic Education, October 1, 1997, https://fee.org/articles/a-century-of-forest-service-ineptitude/.

61. Gates, Jeffersonian Dream, 113.

![[TEST] The Objective Standard](https://test.theobjectivestandard.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/logo.png)