Forty years ago, two films—Alien and Star Trek: The Motion Picture—dazzled audiences not only with pathbreaking special effects, but also with rich musical scores that carried moviegoers into the frightening or awe-inspiring realms of outer space. These soundtracks, different in so many ways, were the brainchildren of one of cinema’s greatest composers, Jerry Goldsmith.

Born in California in 1929, Goldsmith began studying music as a young boy. After college, he landed a job at CBS, which then was producing radio dramas as well as television. He wrote short pieces for radio before graduating to such TV series as The Twilight Zone. In 1968, his score for Planet of the Apes brought him critical attention, and he remained in high demand until his death in 2004.

More experimental than his celebrated contemporary John Williams, Goldsmith employed exotic instruments—everything from Australian didgeridoos to a medieval French instrument called a serpent—to give Alien an eerie, otherworldly quality. And by avoiding any melodic center, he created a suspenseful atmosphere perfect for the film’s blend of science fiction and horror.

Yet he clashed with director Ridley Scott, particularly over the opening theme. “I always think of space,” Goldsmith explained, “not as terrifying, but questioning—sort of an air of romance.”1 Thus his original composition evoked a spirit of discovery, not fear; the horror, he thought, should appear gradually as the plot darkens. “I thought . . . don’t give it all away in the main title.” But Scott wanted the music to convey an uninterrupted tone of anxiety and asked for a new, harsher composition. Goldsmith reluctantly wrote something sufficiently spooky, but he never liked the “weird and strange” result. He always strove for “emotional penetration” he said afterward, “not [just] for complementing the action.”2

His experience with Star Trek was the reverse. Where Alien’s darkness meshed poorly with his sense of life, Star Trek’s humanist aspirations fit his romanticism perfectly. In fact, the mesmerizing music he created rescued the film to some degree from its shortcomings. Forced to rush editing to finish the movie on time, director Robert Wise failed to obtain sound effects for several scenes and relied on Goldsmith’s lush suite as a substitute. “Thank goodness we had Jerry’s score,” he said later. “He really saved us.”

Whereas John Williams drew on Richard Wagner and Erich Korngold for his 1977 Star Wars score, Goldsmith turned to Camille Saint-Saëns and Ralph Vaughan Williams for inspiration on Star Trek—and ramped up his use of unusual tools. To represent the film’s primary antagonist, the space probe V’Ger, he used a “blaster beam”—a twelve-foot-long bass played by banging the strings with an artillery shell. For the Klingons he played castanet-like sounds on an Indonesian instrument called an angklung. Combined with a barbaric theme based on Vaughan Williams’s Symphony no. 4 in F minor and played on trumpets made of animal horns, the piece perfectly evokes the franchise’s warlike villains. Above all, Goldsmith’s soaring march and rapturous symphonic moments easily place Star Trek among his finest work. Although they could not compensate for the film’s other flaws, these pieces made the final result enjoyable and became, as Mauricio Dupuis wrote in Jerry Goldsmith: Music Scoring for American Movies, a “symbol of the [Star Trek] saga.”

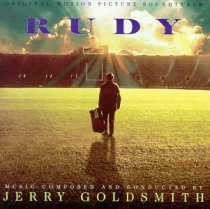

Goldsmith’s versatility was astonishing. The nostalgic fanfare of Patton is totally unlike the mischievous synthesizers of Gremlins or the cheerful Polynesian pipes of Medicine Man. But nothing he wrote, not even Star Trek, exceeded the splendor of his 1993 score for Rudy.

An unabashed celebration of the underdog, Rudy tells the story of football player “Rudy” Ruettiger, an undersized, dyslexic kid who beat the odds to play for his favorite team, Notre Dame’s Fighting Irish. To accompany the inspirational true tale, Goldsmith dispensed with esoteric instruments and drew on the full power of the concert orchestra. A single flute sounds the opening bars of the Irish folk song “The Last Rose of Summer,” evoking Rudy’s smallness and sincerity. The melodies—just a few simple themes—then rise through strings and brass into a triumphant march that evokes idealism beyond any film score ever composed.

The soul-stirring romanticism of Rudy’s soundtrack has made it a modern classic, despite its never receiving any awards. “I’ve always felt a sense of injustice [about that],” said the film’s star, Sean Astin, at a concert performance of the score in March 2019. “All composers know and love and revere Jerry, and they totally love this score.” Still, Goldsmith received recognition of a sort: Rudy’s music often has been recycled to accompany trailers for other films.

The “real challenge” of cinematic music, Goldsmith said, “is to write a score that works brilliantly in a film, and also has a life of its own.”3 For half a century, Goldsmith’s music—whether grand or delicate, haunting or idealistic—bested that challenge.

Click To Tweet

You might also like

Endnotes

1. “Jerry Goldsmith’s score to ‘Alien,’” YouTube, April 26, 2011, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U8bv0QDLI7M&feature=youtu.be&t=481.

2. Jerry Goldsmith, “Welcome To Jerry Goldsmith Online,” Jerry Goldsmith Online, http://www.jerrygoldsmithonline.com/ (accessed June 1, 2019).

3. “Jerry Goldsmith’s score to ‘Alien.’”

![[TEST] The Objective Standard](https://test.theobjectivestandard.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/logo.png)