Author’s note: This essay originally was delivered as a presentation at OCON 2019 and retains the quality of the oral presentation. Notes have been added to provide citations.

Years ago, I gave a talk called “Making Poetry Part of Your Life” that opened with a poem by John Keats called “On First Looking Into Chapman’s Homer.” I had fallen madly in love with this poem for many reasons, some of which I will describe here today. But for now, I will just say that one of those reasons is that it is a poem about new horizons—and it had come to stand in my mind as a stirring account, in the form of poetry, of what it feels like to discover the new horizon of poetry itself.

Poetry had always seemed to me like it was either banal, sing-songy, Hallmark-style rhymes, or else inaccessible, scholarly, erudite verses. The former left me flat; the latter left me . . . intimidated, and a bit skeptical.

But at some point, I experienced an awakening. I don’t recall precisely when, but like most of the art-related turning points in my life, this was one I can likely ascribe to the influence of Dr. Leonard Peikoff.

In my twenties, I was part of a group who met periodically to discuss great plays, and Dr. Peikoff was sometimes part of it as well. For one of our meetings, we turned our focus to poetry, and he read one of his favorite poems and now one of mine: “Rizpah,” by Alfred Tennyson.

I happened to be pregnant with my first child at the time, and hearing him read this stirring poem about a woman whose beloved son was convicted of a petty crime and sentenced to a public hanging, who defied the judge’s orders not to touch her son’s remains and went by night to steal his bones one by one from the foot of the gibbet, and who revered her son, defying the judgment of his executioners and even of God—it is an experience I will never forget.

I witnessed, and felt, the power of poetry to attach to or awaken deep emotions, and, quoting Keats’s “Chapman’s Homer,” “then felt I like some watcher of the skies when a new planet swims into his ken.”

Long after this awakening, and a few years after my first poetry lecture, I took a trip to England with my then teenage daughters, and it was an experience of dazzling, whirlwind bliss. Perhaps the most memorable moment of all was our visit to Keats House.

At that point, I knew and loved not just “On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer,” but “Ode on a Grecian Urn,” and “Bright Star,” among others. I had some vague, fleeting knowledge of Keats’s life story: that he was a contemporary of Shelley, Byron, and Wordsworth, that he suffered poverty and ill-fated love, and that his life was cut tragically short by tuberculosis.

But on this visit to his house, we had the rare good fortune to be led by a genuinely passionate tour guide, someone for whom Keats’s story had clearly touched her soul and who was able to convey that story in a way that touched ours. Listening to her tell her heartfelt tale, while we walked in Keats’s own footsteps, hearing his poetry swirl through our minds, was an experience I can only describe as magical.

I am going to begin Keats’s story at the end and tell you one part of our tour guide’s account that I remember most.

When, at the age of twenty-five, it became clear that Keats was ill beyond the possibility of recovery, and he had to resign himself to death, he gave his friend Joseph Severn instructions about what was to be engraved upon his tombstone. He said he did not want his name to appear on it; instead, only the words, “Here lies one whose name was writ in water.” I can imagine no more achingly beautiful and simply poetic way of capturing the tragic transience of his life.

But though his life may have been transient, his legacy was not. In his short time on earth, he wrote countless poems of immortal beauty that have been beloved for centuries, and I hope, will be for centuries to come. I, at least, will do my part to make them so.

To that end, I want to spend our next hour together acting as your impassioned tour guide, through the life and the poetry of John Keats. I wish I could be doing so in Keats House, but we can’t have everything. At least not right now. Maybe someday you can join me there.

John Keats was born in London on October 31, 1795. He was the eldest of four children, including brothers Tom and George and sister Frances. Keats’s father managed and later owned his father’s stable, a job which earned him a comfortable living and enabled him to send his sons to the well-regarded Clarke’s Academy in Enfield.

It was while at Enfield that Keats suffered the first of the many terrible tragedies he would endure. At the age of eight, when Keats had been at Enfield just a year, his father paid him a visit. At some point on his late-night ride home, Keats’s father fell from his horse and smashed his skull on the pavement; the watchman who found him remarked on the amount of blood. He was beyond saving, and all they could do was carry him home to die. By eight the next morning, he was gone. Keats would afterward suffer not just the loss of a parent, but a terrible feeling of guilt that if his father hadn’t come to visit, he might have lived.

Just two months after his father’s death, Keats’s mother married a man considerably her junior, with no money or property, who would endeavor, with no experience, to take over the family business. He seems to have been little more than a fortune hunter, and within two years they had suffered financial devastation and their marriage had come to an end.

Keats’s mother then took her children to live with their grandmother, and soon after suffered a rapid decline of health. She developed severe tuberculosis, and fourteen-year-old Keats is said to have devotedly attended her sick bed. Quoting a biography by Sidney Colvin, “He sat up whole nights with her in a great chair, would suffer nobody to give her medicine, or even cook her food, but himself, and read novels to her in her intervals of ease.” She died at the age of thirty-five, and Keats is also said to have bitterly mourned her death: “He gave way to such impassioned and prolonged grief (hiding himself in a nook under the master’s desk) as awakened the liveliest pity and sympathy in all who saw him.”1

His grandmother’s death would follow soon after his mother’s, and she left the children a trust that should have meant they were well provided for, if, as biographer Nicholas Roe says ominously, “[they had] actually known what provisions had been made for them.”2

Keats would one day write in a letter that he had “never known any unalloy’d Happiness for many days together: the death or sickness of some one has always spoilt my hours.”3 What little happiness he did enjoy in these trying years came from his time at school in Enfield.

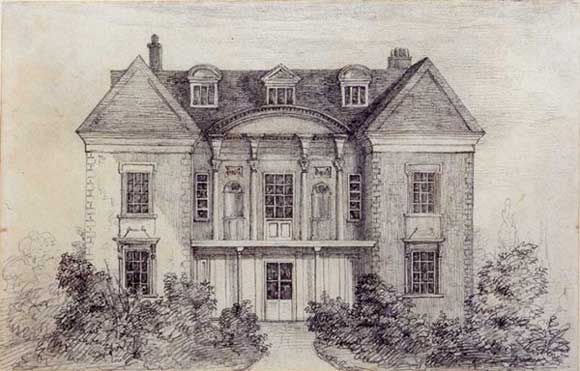

Biographer Roe describes Enfield as idyllic and as having inspired many a paradisiacal scene in Keats’s verses. The school was a Georgian mansion of polished brick adorned with molds of flowers and pomegranates, with airy, spacious rooms behind latticed windows. Across a playground with a pear tree was a walled garden with a pond, strawberry beds, and a rustic arbor, and beyond that, a paddock for cows that supplied the school milk.4

Enfield was a school that defied stuffy tradition. The teachers encouraged open minds on religious matters; instead of the customary floggings for mischief, children were encouraged to keep records of their own behavior; astronomy was learned by observation through a telescope or model solar systems constructed in the garden; rather than the classic Eton Latin Primer, students learned from Lemprière’s Bibliotheca Classica, a book packed with doctrines of classical republicanism and democracy and considered by conservatives a primer for sedition. Keats devoured it.

In his “Recollections of Keats,” friend and tutor Charles Cowden Clarke wrote,

In the early part of his school-life John gave no extraordinary indications of intellectual character; but it was remembered of him afterwards, that there was ever present a determined and steady spirit in all his undertakings: I never knew it misdirected in his required pursuit of study. He was a most orderly scholar. The future ramifications of that noble genius were then closely shut in the seed, which was greedily drinking in the moisture which made it afterwards burst forth so kindly into luxuriance and beauty.5

Keats would form with Cowden Clarke, who was the son of Enfield’s headmaster, one of his most important and formative friendships.

Cowden Clarke was eight years older than Keats and an assistant teacher, beloved at the school, who led by the example of his own enthusiasm for life and learning. Roe says admiringly of him that “he was as commanding in the schoolroom as he was on a cricket pitch,” that he shared his love of literature “by pointing out . . . passionate passages,” that when his favorite actors were performing in London “he would set off to walk twelve miles to see them . . . returning . . . by moonlight,” and that his influence on Keats was decisive.6 It was Cowden Clarke who opened Keats’s eyes to Edmund Spenser, whose Faerie Queene Keats says he first went through “as a young horse would through a spring meadow—ramping!” Spenser would become one of Keats’s greatest inspirations, and Keats would one day dedicate to him a sonnet of his own, in which he longs as a “jealous honourer” to write verses that would please Spenser. He closes by saying, “Be with me in the summer days and I / Will for thine honour and this pleasure try.”7

It was also Cowden Clarke who introduced him to the Chapman translation of Homer.

After the death of his mother, when he was fourteen, Keats was obliged to leave Enfield to be apprenticed to an apothecary. For many years thereafter, he would cross a bridge over Salmon’s Brook to Enfield five or six times a month to meet with Cowden Clarke and to feed his love of poetry. These visits would last late into the evening, with the two friends reading in the garden and, after it fell dark, talking into the early hours of the morning.

At one of their encounters, when Keats was twenty, Cowden Clarke shared with Keats a folio edition of Chapman’s translation of Homer, which had been lent to him by one of Keats’s heroes, the radical poet Leigh Hunt. Cowden Clarke recalled that he and Keats spent a “wine-warmed” evening poring over famous passages and relishing their “muscular music.” Chapman’s translation was a revelation to Keats and opened his eyes like nothing before to Homer’s “realms of gold.”

In the early hours of the morning, Keats walked home and sat down to write a sort of thank-you note to Cowden Clarke that would memorialize the thrill of that eye-opening experience. He had finished it, addressed it, and sent it to Cowden Clarke before ten that same morning. That “thank-you note” is the beloved sonnet “On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer.”

In it, Keats describes how he had read many tributes by great poets to the “goodly states,” “kingdoms,” and “western islands” of Greek legend, the foremost among them being those of Homer, whom he knows to be the ruler of this “demesne.” But, he feels he never properly appreciated the work of Homer, never breathed it, until he read Chapman’s translation. He likens the experience to that of an astronomer discovering a new planet, or an explorer being the first to gaze out upon a previously undiscovered ocean.

Here is “On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer.”

Much have I travell’d in the realms of gold,

And many goodly states and kingdoms seen;

Round many western islands have I been

Which bards in fealty to Apollo hold.

Oft of one wide expanse had I been told

That deep-brow’d Homer ruled as his demesne;

Yet did I never breathe its pure serene

Till I heard Chapman speak out loud and bold:

Then felt I like some watcher of the skies

When a new planet swims into his ken;

Or like stout Cortez when with eagle eyes

He star’d at the Pacific—and all his men

Look’d at each other with a wild surmise—

Silent, upon a peak in Darien.

I hope the context I established for this poem allowed you to enjoy it, to “breathe” it, without effort. Let me tell you, when I encountered it the first time, absent context, unfamiliar with many of the words, and intimidated by the metaphors and the syntax, I struggled. But after sitting with it, looking up those words, seeking helpful analysis, and reading a bit about the context in which it was written, it became dazzlingly clear—and it now reads to me like a melodious and eloquent anthem to new horizons.

How fortunate Keats was to have a friend and teacher such as Cowden Clarke, with whom he could spend “wine-warmed” evenings rhapsodizing over poetry, and from whom he parted with reluctance in the early hours of the morning. Keats captured his own appreciation for this good fortune in another poem called “To Charles Cowden Clarke.”

Keats begins with an image of a swan with proud breast and outspread wings, slanting his neck beneath the waters and ruffling the surface of the lake, as if in an effort to take the diamond drops of water and keep them nestled in his milky down. But alas, they rush down his feathers “as though they would be free” and, as impossible to stop as the passing of time, they “drop like hours into eternity.” Keats then likens the swan’s efforts to hold those diamond drops to his own desperate efforts to capture his feelings . . . in poetry.

Here is an excerpt from “To Charles Cowden Clarke.”

Oft have you seen a swan superbly frowning,

And with proud breast his own white shadow crowning;

He slants his neck beneath the waters bright

So silently, it seems a beam of light

Come from the galaxy: anon he sports,—

With outspread wings the Naiad Zephyr courts,

Or ruffles all the surface of the lake

In striving from its crystal face to take

Some diamond water drops, and them to treasure

In milky nest, and sip them off at leisure.

But not a moment can he there insure them,

Nor to such downy rest can he allure them;

For down they rush as though they would be free,

And drop like hours into eternity.

Just like that bird am I in loss of time,

Whene’er I venture on the stream of rhyme;

With shatter’d boat, oar snapt, and canvass rent,

I slowly sail, scarce knowing my intent;

Still scooping up the water with my fingers,

In which a trembling diamond never lingers.

In the next excerpt, he explains that he has tried in vain to write verses that pay fitting tribute to his very literate friend. He has longed to pen a poem to Cowden Clarke, whom he has known so long, who taught him all the beauty of poetry, who is responsible for the only joys of his tragic youth, and without whom his life would be bereft of meaning. But he has felt unworthy of the task; it is a debt he fears he can never repay. However, if ever he does succeed, he says, he will be doubly satisfied: first, in having paid successful tribute to his beloved friend, and second, in having written verses that this cultured scholar considers worth reading. Here is the second excerpt.

By this, friend Charles, you may full plainly see

Why I have never penn’d a line to thee:

Because my thoughts were never free, and clear,

And little fit to please a classic ear . . .Thus have I thought; and days on days have flown

Slowly, or rapidly—unwilling still

For you to try my dull, unlearned quill.

Nor should I now, but that I’ve known you long;

That you first taught me all the sweets of song:

The grand, the sweet, the terse, the free, the fine;

What swell’d with pathos, and what right divine . . .Ah! Had I never seen,

Or known your kindness, what might I have been?

What my enjoyments in my youthful years,

Bereft of all that now my life endears?

And can I e’er these benefits forget?

And can I e’er repay the friendly debt?

No, doubly no;—yet should these rhymings please,

I shall roll on the grass with two-fold ease:

For I have long time been my fancy feeding

With hopes that you would one day think the reading

Of my rough verses not an hour misspent;

Should it e’er be so, what a rich content!

The last excerpt is my very favorite of all, with Keats reflecting on one of their evenings together, “warm’d luxuriously by divine Mozart,” walking together “through shady lanes,” immersing themselves in his books, and reveling in a conversation that they never wanted to end. And then, the moment that they separate, midway between their two homes, and shake hands—and Keats, so moved by this common ritual, listens carefully to the sound of Cowden Clarke’s footsteps fading in the distance. Here is excerpt three.

But many days have past since last my heart

Was warm’d luxuriously by divine Mozart;

By Arne delighted, or by Handel madden’d;

Or by the song of Erin pierc’d and sadden’d:

What time you were before the music sitting,

And the rich notes to each sensation fitting.

Since I have walk’d with you through shady lanes

That freshly terminate in open plains,

And revel’d in a chat that ceased not

When at night-fall among your books we got:

No, nor when supper came, nor after that,—

Nor when reluctantly I took my hat;

No, nor till cordially you shook my hand

Mid-way between our homes:—your accents bland

Still sounded in my ears, when I no more

Could hear your footsteps touch the grav’ly floor.

Sometimes I lost them, and then found again;

You chang’d the footpath for the grassy plain.

I am “warmed luxuriously” by this divine tribute to friendship. I will carry with me forever the image of that proud swan, trying in vain to tuck the diamond drops in his wings so that he might sip them later, and the metaphor of Keats’s attempt to capture his gratitude to his friend in verse by scooping up words like water, and seeing the trembling diamonds fall from his grasp.

I love his expression of the debt of inspiration he owed his friend and tutor, who “taught him all the sweets of song: the grand, the sweet, the terse, the free, the fine, what swell’d with pathos, and what right divine.” I am especially fond of those lines, because I could use them to capture my own ambition. Every day of my life I am endeavoring to teach my students “the sweets of song.”

And most of all, I am moved by the depth of their friendship, with memories so sweet that Keats is compelled to commemorate them in poetry, and evenings so enjoyable that when they part with a handshake, he would stop to listen attentively to the sound of his friend’s retreating footsteps.

Mid-way between our homes:—your accents bland

Still sounded in my ears, when I no more

Could hear your footsteps touch the grav’ly floor.

Sometimes I lost them, and then found again;

You chang’d the footpath for the grassy plain.

I hope some of you feel that way, and recall that image, when you part from friends with whom you have reunited here.

Another of Keats’s formative influences and life-altering encounters was a man I mentioned in passing earlier, the radical poet Leigh Hunt. His introduction to Hunt was one long sought after, and, when it arrived, one that turned the tides of his life and arguably made his poetic legacy possible.

Hunt was a seemingly fearless rebel; he was an editor of and essayist for the radical paper The Examiner, which advocated abolition of the slave trade, Catholic emancipation, and reform of criminal law. He was also a poet, an antagonist of the rigidity of neoclassical standards, and a champion of natural expression. Eventually, he would be known for having introduced the world, not just to Keats, but to Shelley, Browning, and Tennyson.

Keats read many an issue of The Examiner at the home of Cowden Clarke, and both men admired Hunt greatly, referring to him in their conversations and their correspondence as “Libertas.”

Hunt pulled no political punches, and when he printed an article excoriating the brutal punishments exacted by the British Army, he was charged with seditious libel, but that time, quickly tried and acquitted. He would earn the reputation of a martyr for liberty by continuing to publish still more scornful and scathing articles, including an attack on the Prince Regent, whom he called “a violator of his word, a libertine over head and ears in debt and disgrace, a despiser of domestic ties, the companion of gamblers and demireps” and “a man who has just closed half a century without one single claim on the gratitude of his country or the respect of posterity.”8 Maybe not surprisingly, this time, he was indicted, found guilty, and sentenced to two years in prison. It was shortly after this publication, and before his trial, that Cowden Clarke had the opportunity to meet his hero in person and to become his friend. Hunt’s prison experience is my favorite part of his story.

As Roe tells it,

Unlike the majority of felons, Hunt was a ‘gentleman,’ and this brought privileges. He imported his own furniture, improved the walls with rose-trellised paper, painted a sky-blue ceiling with billowy summer clouds, and screened a view to the gallows with window-blinds. Bookcases, books, and busts of the poets came in, and a furniture carrier arrived with a piano. Flowers and greenery were planted in the yard outside, and a lute completed a scene of romantic seclusion.9

He went on from prison supplying copy for and editing The Examiner, and in fact, the celebrity that came from his imprisonment dramatically increased its sales. Cowden Clarke would visit Hunt in prison, bringing him baskets of eggs, vegetables, fruit, and flowers from the Enfield garden. Keats hoped for an invitation to join him on one of these visits, but it never came.

Roe imagines that stories of Hunt’s embowered prison retreat might have inspired Keats’s vision of the “rosy sanctuary” in “Ode to Psyche.” Whether or not it did, it is a sensible connection to an enchanting poem. So let’s take a moment to look at it.

In a letter to his brother and sister, Keats describes his inspiration for “Ode to Psyche” like this:

You must recollect that Psyche was not embodied as a goddess before the time of Apuleius the Platonist, who lived after the Augustan Age, and consequently the goddess was never worshipped or sacrificed to with any of the ancient fervour, and perhaps never thought of in the old religion. I am more orthodox than to let a heathen goddess be so neglected.10

In this poem, he proclaims Psyche worthy of worship and promises himself to build an altar to her and to be her priest. More abstractly, it can be regarded as a tribute to the independent and creative mind, both because Psyche represents a spirit of imagination and because the poet must create a shrine to her in his own imagination.

I take the connection to Hunt suggested by Roe to be both that he himself could be regarded as a hero unworshipped in his time and that he had to create his own “imaginative altar” while captive in prison.

In the excerpt from “Ode to Psyche” below, Keats pledges himself as a priest to Psyche, who will build a temple to her in some untrodden region of his mind. There, thoughts rather than pines will branch and murmur in the wind. Trees, mountains, birds, and bees will stand far away in the distance, and in his “wide quietness” he will build a rosy sanctuary with the trellis of a “working brain.” There, he will breed all the buds and bells and stars and delights that can be created by fancy. And there, within those shadowy thoughts, there will be a bright torch and open window to let love in.

Here is the excerpt:

Yes, I will be thy priest, and build a fane

In some untrodden region of my mind,

Where branched thoughts, new grown with pleasant pain,

Instead of pines shall murmur in the wind:

Far, far around shall those dark-cluster’d trees

Fledge the wild-ridged mountains steep by steep;

And there by zephyrs, streams, and birds, and bees,

The moss-lain Dryads shall be lull’d to sleep;

And in the midst of this wide quietness

A rosy sanctuary will I dress

With the wreath’d trellis of a working brain,

With buds, and bells, and stars without a name,

With all the gardener Fancy e’er could feign,

Who breeding flowers, will never breed the same:

And there shall be for thee all soft delight

That shadowy thought can win,

A bright torch, and a casement ope at night,

To let the warm Love in!

Whether you envision a true shrine to Psyche, or Hunt’s temple within a prison, or Keats’s own private space for poetic imagination—I love the idea of building a temple in “some untrodden region of your mind.” Whatever our external circumstances, we can create in its midst a world of our own, “with buds, and bells, and stars without a name, / With all the gardener Fancy e’er could feign, / Who breeding flowers, will never breed the same.” And instead of suffering bitterness or resentment, we can enjoy “all soft delight that shadowy thought can win, a bright torch, and a casement ope at night, to let warm Love in.”

Having long desired an introduction to Hunt that was not forthcoming, Keats treated the occasion of Hunt’s release from prison as an opportunity. He thought perhaps he could contrive an introduction by writing a poem to celebrate Hunt’s freedom. Knowing that Cowden Clarke would walk to London to see Leigh Hunt when he was released, Keats orchestrated an encounter with him, and hesitatingly offered him the sonnet “Written on the Day that Mr. Leigh Hunt left Prison.” Cowden Clarke did not take the hint, for reasons we can never know. Roe speculates that perhaps he was envious that despite his own poetic ambitions and cultivated friendship with Hunt, he did not think to write such a poem to celebrate the occasion. The poem was never given to Hunt, but it did later find its way into Keats’s first published collection, so Hunt eventually would read it. And, in fact, he himself would one day write a sonnet called “To John Keats.”

In his sonnet, Keats pays bold and defiant tribute to Hunt’s “immortal spirit” and heaps contempt upon the servile minions who put him in prison. He mocks their vain efforts to stifle Hunt and says that even in prison, he has been as free as the flying lark. Though physically captive, he, just like Keats described in the “Ode to Psyche,” forged his own world, where he strayed the halls of Spenser, flew through the air with Milton, and found himself in the happy regions of his own genius. Hunt’s spirit, he says, is immortal, whereas the “wretched crew” who tried to stop him will die out, with none to replace them.

Here is “Written on the day that Mr. Leigh Hunt left Prison”:

WHAT though, for showing truth to flatter’d state,

Kind Hunt was shut in prison, yet has he,

In his immortal spirit, been as free

As the sky-searching lark, and as elate.

Minion of grandeur! think you he did wait?

Think you he nought but prison walls did see,

Till, so unwilling, thou unturn’dst the key?

Ah, no! far happier, nobler was his fate!

In Spenser’s halls he strayed, and bowers fair,

Culling enchanted flowers; and he flew

With daring Milton through the fields of air:

To regions of his own his genius true

Took happy flights. Who shall his fame impair

When thou art dead, and all thy wretched crew?

I love the description of Hunt’s alleged sedition as “showing truth to flatter’d state.” I love the scorn in his description of Hunt’s enemies as “minions of grandeur” and as a “wretched crew” helpless to impair his fame, and I love the boastful defiance in his insistence that in all the time Hunt spent locked away, he never saw a prison wall. Instead, “In Spenser’s halls he strayed, and bowers fair, / Culling enchanted flowers; and he flew / with daring Milton through the fields of air: / To regions of his own his genius true took happy flights.”

Perhaps you have your own favorite image of a man standing proud and defiant before his imprisoners, demonstrating that his spirit defies capture, and you can connect that image to the one Keats has created for us here. I have always been partial to the image of Nathan Hale proclaiming his regret that he has but one life to give for his country, captured in the statue outside New York’s city hall.

Given his admiration of Hunt and the inspiration he drew from The Examiner, you can imagine Keats’s thrill when in 1816 he saw published in tiny print at the bottom of one of The Examiner’s pages, “J.K., and other communications, next week.” The next week, he scanned the paper until he came to his poem “To Solitude,” and beneath it, the initials J. K. This was Keats’s first published poem, and in his hero’s publication, The Examiner. Keats’s admiration of Hunt had only grown with the release of Hunt’s poem “The Story of Rimini,” a poem based on the tale of doomed lovers Paolo and Francesca in Dante’s The Inferno and written in heroic couplets. Keats considered it a revelation.

Roe says that in Hunt’s characteristic effort to bring poetry “into energetic conversation with public issues,” he placed Keats’s poem between the story of a botched incision that led a soldier to bleed to death and an article on the distress and ruin of farmers.11 I imagine it something like finding a poem by Keats nestled between clickbait headlines on Buzzfeed.

Hunt published “J.K.” not knowing who he was. It was only later, after Cowden Clarke read the sonnet Keats had written for him, “To Charles Cowden Clarke,” that he finally proposed that Keats send him a few poems he might show to Hunt. Perhaps that is because within his tribute to his friend Cowden Clarke, he had included some not-so-subtle hints: referencing their mutual admiration of “Libertas” and reminding Cowden Clarke of the moment he handed him the poem celebrating Leigh Hunt’s release from prison.

So, Cowden Clarke did bring some of Keats’s poems to Hunt, and he recalls in his memoir about Keats the “prompt admiration which broke forth before [Hunt] had read twenty lines of the first poem” (Roe, 100). After making eager inquiries about him, Hunt asked Cowden Clarke to extend an invitation to Keats to come to Hunt’s home in the Vale of Health.

After an unavoidable delay caused by Keats’s duties as an apothecary, he wrote to Cowden Clarke to say, “I can devote any time you may mention to the pleasure of seeing Mr. Hunt—t’will be an Era in my existence.”12 It would.

Before we move on to a discussion of that “Era,” let’s take a look at Keats’s first published poem, the one Hunt put in The Examiner, and one of my personal favorites from among his works, “To Solitude.”

“To Solitude” begins as a hymn to the beauty of Nature. If he must be alone, Keats says, let it not be “among the jumbled heap of murky buildings” in the city. Instead, let him “climb the steep” to Nature’s observatory, where he might enjoy the sight of flowery slopes, crystal rivers, leaping deer, and bees buzzing among the foxgloves.

But though he can be happy enjoying this idyll alone, he can imagine no higher bliss, no more soulful pleasure, than fleeing to nature along with some kindred spirit whose thoughts mirror his own. This tribute to solitude is an exquisite tribute to friendship:

O SOLITUDE! if I must with thee dwell,

Let it not be among the jumbled heap

Of murky buildings; climb with me the steep,—

Nature’s observatory—whence the dell,

Its flowery slopes, its river’s crystal swell,

May seem a span; let me thy vigils keep

’Mongst boughs pavillion’d, where the deer’s swift leap

Startles the wild bee from the fox-glove bell.

But though I’ll gladly trace these scenes with thee,

Yet the sweet converse of an innocent mind,

Whose words are images of thoughts refin’d,

Is my soul’s pleasure; and it sure must be

Almost the highest bliss of human-kind,

When to thy haunts two kindred spirits flee.

When I teach this poem to my students, I use it as an opportunity for them to travel, in imagination at least, to the English countryside. Many of them have experienced no landscapes outside of the California desert, and they delight in the mellifluous descriptions that I accompany with pictures of the dell, the flowery slopes, the river’s crystal swell, the boughs pavillion’d, the deer’s swift leap, and the wild bee startled from the foxglove bell. I am especially partial to the English countryside, so it is an opportunity for me to dwell there, too.

But I am more moved still by Keats’s account of the sort of friendship he longs for: “the sweet converse of an innocent mind, whose words are images of thoughts refin’d,” a “kindred spirit” whose company amid that beauty would satiate his soul and allow him to experience the “highest bliss of human-kind.” A painting by Asher Brown Durand from the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City portrays this sentiment, and it is aptly titled Kindred Spirits.

When Hunt read this poem, he knew the author only as J. K. But on Saturday, October 9, 1816, Keats would finally meet his hero in the flesh. Hunt spoke knowledgeably about books, poetry, politics, painting, and more, and Keats apparently found him approachable and quickly felt at ease. Also present at that first encounter was a very talented, but also famously combative and self-aggrandizing painter, Henry Haydon, whose stormy life eventually would end with his suicide. Apparently, Haydon and Hunt were both electrified by Keats and began vying with each other for his attention. Through Hunt, Keats would meet not just Haydon, but Charles and Mary Lamb, Percy Shelley, and eventually even William Wordsworth. Cowden Clarke recalls that in one of their early encounters, when Keats attempted to express disagreement with Wordsworth, the renowned poet’s wife put her hand on his arm and said, “Mr. Wordsworth is never interrupted.”13 Images of both Wordsworth and Keats can be found among the crowd in Haydon’s grand masterpiece Christ’s Entry into Jerusalem.

Keats’s “new era” included admission into a literary and artistic world where he was hailed by Hunt as one of three young poets who belonged to a new and rising school of poetry, the other two being Shelley and John Reynolds.

Keats would pay tribute to his new literary and artistic society in his poem “Great Spirits.” Let’s take a look at it now.

Great spirits now on earth are sojourning;

He of the cloud, the cataract, the lake,

Who on Helvellyn’s summit, wide awake,

Catches his freshness from Archangel’s wing:

He of the rose, the violet, the spring,

The social smile, the chain for Freedom’s sake:

And lo!—whose stedfastness would never take

A meaner sound than Raphael’s whispering.

And other spirits there are standing apart

Upon the forehead of the age to come;

These, these will give the world another heart,

And other pulses. Hear ye not the hum

Of mighty workings in the human mart?

Listen awhile ye nations, and be dumb.

I love the unbridled hero worship of the opening line. “Great spirits now on earth are sojourning.”

And who are these great spirits? First, “He of the cloud, the cataract, the lake / Who on Helvellyn’s summit, wide awake, / Catches his freshness from Archangel’s wing.” Any idea who that might be? William Wordsworth.

And then, “He of the rose, the violet, the spring, / The social smile, the chain for Freedom’s sake.” That, of course, is Leigh Hunt.

And finally, “And lo!—whose steadfastness would never take a meaner sound than Raphael’s [the great Renaissance painter’s] whispering.” That is a reference to Haydon.

Then, having paid tribute to these “Great Spirits,” whose company he is fortunate to keep, he goes on to say:

And other spirits there are standing apart

Upon the forehead of the age to come;

These, these will give the world another heart

And other pulses.

I love the idea of history’s great geniuses as giving the world “another heart and other pulses.” They don’t just improve the world as it is—they entirely remake it and give it new life. And finally, the bold hero worship evident in the opening line is still bolder at the poem’s close. Keats commands the world to attend the work of these mighty spirits in awed silence. “Listen awhile, ye nations, and be dumb.”

Keats’s first publication and his entry into this community of “great spirits” was a happy chapter in the life that never allowed him unalloyed happiness. And, tragically, he was about to face greater sorrows still.

In 1818, Keats’s younger brother George turned twenty-one and received a small part of their inheritance. He married and decided to move with his new wife to America, where property could be acquired cheaply, and he could begin his career as a farmer. Keats had depended on George’s belief in his genius and the management of his worldly concerns. The news of George’s marriage and his intention to go abroad left Keats numb.

To make matters worse, Keats’s other brother, Tom, would begin to show signs of consumption, the disease that had claimed the life of their young mother. Keats was living in Hampstead, where he could enjoy the company of his literary friends, and one day in August he was summoned by the doctor to attend to Tom in London, saying he was extremely ill.

For months, Keats would be confined almost entirely to Tom’s room, nursing him in the final stages of his disease. He would lie awake at night, listening to Tom’s fevered restlessness and endeavor to keep him still during the day so that he would not hemorrhage blood. Keats was intensely devoted to his brother, yet he could not help but feel trapped. “His identity presses upon me so all day, so that I am obliged to go out,” he told a friend, but he acknowledged also that Tom looked upon him as his only comfort.

On December 1, Tom died, and Keats went to see his friend Charles Brown, who was living at Wentworth Place, the house where I walked the halls, and that is now known as Keats House.

Brown describes the moment like this: “Early one morning, I was awakened in my bed by a pressure on my hand. It was Keats, who came to tell me that his brother was no more. At length . . . I said, ‘Have nothing more to do with those lodgings, and alone too. Had you not better live with me?’” Keats replied, “I think it would be better.” It would be an auspicious moment in the life of Keats: one that would bring great joy and further sorrows.

Before I go on with Keats’s story, I want to share with you a poem he wrote that captures the depth of his despair over the tragedies of his childhood and the painful loss of his father, mother, and dear brother. It is called, “In Drear Nighted December.”

In the first stanza, Keats expresses how fortunate the trees are that in the barrenness of “drear-nighted December,” they do not remember that there was a time they burst with leafy life in the green of spring. And more, the sleety winds and frozen nights of winter will never stop them from budding anew each year when spring returns.

The second stanza carries on this theme. Frozen winter brooks do not recall their happy bubblings. Thoughts of summer joys freeze with the freezing of their waters, and they forget, never fretting over the loss.

He longs for the same to be true of man—that he could be steeled to loss, that he could be numbed to it—that he could forget. But instead, he is doomed to writhe under the pain of passed joys.

In drear-nighted December,

Too happy, happy tree,

Thy branches ne’er remember

Their green felicity—

The north cannot undo them

With a sleety whistle through them

Nor frozen thawings glue them

From budding at the prime.In drear-nighted December,

Too happy, happy brook,

Thy bubblings ne’er remember

Apollo’s summer look;

But with a sweet forgetting,

They stay their crystal fretting,

Never, never petting

About the frozen time.Ah! would ’twere so with many

A gentle girl and boy—

But were there ever any

Writh’d not of passed joy?

The feel of not to feel it,

When there is none to heal it

Nor numbed sense to steel it,

Was never said in rime.

“The feel of not to feel it.” I don’t know what it is about that. So simple, and it caught my breath. My heart aches for Keats in all of his suffering, but it also soars from his ability to capture a universal longing and to give us words to console us in our own grief.

There are echoes of this same theme, of a longing to escape the burden of past sorrows, in one of the five great odes hailed by critics and beloved by generations of readers: “Ode to a Nightingale.”

The story behind the composition of this timeless poem is another that I fondly recall from my tour. According to Keats’s friend and roommate Charles Brown,

In the spring of 1819 a nightingale had built her nest near my house. Keats felt a tranquil and continual joy in her song; and one morning he took his chair from the breakfast-table to the grass plot under a plum-tree, where he sat for two or three hours. When he came into the house, I perceived he had some scraps of paper in his hand, and these he was quietly thrusting behind the books. On inquiry, I found these scraps, four or five in number, contained his poetic feeling on the song of our nightingale. The writing was not well legible; and it was difficult to arrange the stanzas on so many scraps. With his assistance I succeeded, and this was his ‘Ode to a Nightingale’, a poem which has been the delight of everyone.14

Incidentally, a plum tree currently grows in the yard of Keats House, planted there in honor of this story and this poem.

So, one great sonnet was a hastily scrawled thank-you letter, and another, some scratch-paper thoughts stuffed behind books on a shelf.

As Keats sat beneath that plum tree, he reflected on the contrast between his own painful heartache and the nightingale’s ecstatic requiem. In the excerpt from this poem that I included in your handout, he imagines drinking some draught of vintage, “cool’d a long age in the deep-delved earth,” that will dissolve away his despair and allow him like the trees and brooks of “Drear Nighted December” to forget his sorrows, or, like the Nightingale, never to have known them at all.

That I might drink, and leave the world unseen,

And with thee fade away into the forest dim:Fade far away, dissolve, and quite forget

What thou among the leaves hast never known,

The weariness, the fever, and the fret

Here, where men sit and hear each other groan;

Where palsy shakes a few, sad, last gray hairs,

Where youth grows pale, and spectre-thin, and dies;

Where but to think is to be full of sorrow

And leaden-eyed despairs;

Where Beauty cannot keep her lustrous eyes,

Or new Love pine at them beyond tomorrow.

Though he is bound to an earth that he describes with such poignant despair as a place “where men sit and hear each other groan,” later in the poem he vows that he will fly to the nightingale in its haven of happiness—“on the wings of poesy”—and that, indeed, in composing these reflective lines, he already has.

In an article published by the British Library, Stephen Hebron captures eloquently this complex poem’s essence: He says that it is “an intense meditation on the contrast between the painful mortality that defines human existence and the immortal beauty found in the nightingale’s carefree song; and it considers poetry’s ability to create a kind of rapt suspended state between the two.”15

It was Keats’s last bout with the painful mortality of human existence, the death of his brother, that brought him to Charles Brown at Wentworth Place. I said that move was an auspicious one. That is because it was there that the legendary romance blossomed between Keats and Fanny Brawne.

Wentworth Place consisted of two semidetached houses separated by a wall. The other house was let by the Dilkes, and on his visits to Brown before moving in, Keats had previously met the Dilkes and their friends the Brawnes. Keats’s first impression of Fanny Brawne is captured in a letter to his brother that contains this rather inauspicious description:

Shall I give you Miss Brawne? She is about my height with a fine style of countenance of the lengthened sort—she wants sentiment in every feature—she manages to make her hair look well—her nostrils are fine though a little painful—her mouth is bad and good—her Profile is better than her full-face which indeed is not full but pale and thin without showing any bone—her shape is very graceful and so are her movements—Her arms are good her hands badish—her feet tolerable. . . . She is not seventeen—but she is ignorant—monstrous in her behavior flying out in all directions, calling people such names that I was forced lately to make use of the term Minx—this I think not from any innate vice but from a penchant she has for acting stylishly. I am however tired of such style and shall decline any more of it.

But because the Brawnes were friends with the neighboring Dilkes, after Keats moved in with Brown he saw more of Fanny, and his impression of her began to . . . evolve.

Keats would spend Christmas Day with the Brawne family at their home, Elm Cottage, and Fanny later reflected to Keats’s sister that this was “the happiest day she had ever spent.”16 In January, he gave his copy of Hunt’s Literary Pocket Book to Fanny, and in its cover, she transcribed lines from a poem Keats was writing called The Eve of St. Agnes. It is a love poem that includes the line, “Lift the latch, ah gently! ah, tenderly, sweet, / We are dead if that latchet gives one little chink.” Fanny would come to regard this poem as the “latchet” on their love for each other.

That summer, the Dilkes moved out of Wentworth Place, and the Brawnes moved in. Now meeting regularly in the garden, and forming a better acquaintance, Keats and Fanny would soon be madly in love. An understanding was formed between them, and they considered themselves engaged, though practically, they could make no plans to marry, and they kept their engagement a secret. Because Keats, as I mentioned before, did not know of his inheritance, and because he had given up his work as an apothecary to devote himself to poetry, he did not have the resources, property, or income that would make it possible for him to marry. Making his living as a poet was now essential, and he made the difficult decision to leave Hampstead, and Fanny, for the Isle of Wight so that he could focus on writing and make his fortune.

There he stayed at Eglantine Cottage, from which he could gaze out the window “over house tops and cliffs onto the Sea.”17 Upon his arrival, he wrote out a letter of “passionate rhapsodies” to Fanny, and then, deciding it was too much too soon, never posted it. He started writing to Fanny with each new phase of the moon, describing himself as compelled to do so as if she had absorbed him in spite of himself.

In July, Keats wrote to Fanny, “I have seen your comet,” and later, he would end another letter, saying, “I will imagine you Venus tonight and pray, pray, pray to your star like a Heathen. Yours ever, fair star, John Keats.”18 The description of this comet in the London papers now seems a tragic portent of what was to come: “probably the present comet has long traversed ethereal space, and is now rapidly making its way toward the sun . . . in which case it will become more brilliant in approaching the sun, but appear to sink towards the northern horizon, and very soon become invisible.”19

Some scholars believe that it is while he was on the Isle of Wight that Keats wrote the sublime poem “Bright Star.”

In this poem, Keats gazes upon a star and longs for its immortality, its steadfastness, its unchangeableness. But, he wants its immortality without its distant, solitary remoteness. He does not want to be like the star, “nature’s pious hermit,” hanging in the sky with eternal, watchful eye, looking down upon the tides as they cleanse the earth or upon the pure, new, soft-fallen snow on the mountains and the moors.

He wants to live forever pillowed upon his fair love’s ripening breast, feeling it fall and swell, and hearing her tender breath. He wants to be “awake for ever” in this “sweet unrest,” or else die on the spot from the pleasure of it.

The poem reads:

Bright star, would I were stedfast as thou art—

Not in lone splendour hung aloft the night

And watching, with eternal lids apart,

Like nature’s patient, sleepless Eremite,

The moving waters at their priestlike task

Of pure ablution round earth’s human shores,

Or gazing on the new soft-fallen mask

Of snow upon the mountains and the moors—

No—yet still stedfast, still unchangeable,

Pillow’d upon my fair love’s ripening breast,

To feel for ever its soft fall and swell,

Awake for ever in a sweet unrest,

Still, still to hear her tender-taken breath,

And so live ever—or else swoon to death.

It is so easy to imagine the feelings that animated and inspired Keats’s poem. Cut off from his love, by distance, by poverty, by societal standards, he longs for her touch. And being all too familiar with the transience of life, he longs for it to endure forever.

This poem juxtaposes brilliantly images of purity, chastity, and asceticism with sensual, earthly, fleshly pleasures.

Instead of gazing upon the snow-covered mountains, he wants to be pillowed on his lover’s ripening breast. Instead of watching the ebb and flow of the tides in their priestlike task of ablution, he wants to feel forever her breast’s rise and swell. Instead of the coldness of the mantle of new-fallen snow that purifies the moors, he wants to feel the warmth of her tender-taken breath.

He wants to live forever. But usually, we imagine eternity to be reserved for the spirit. He wants to live the life of the body forever.

The last line reminds me of the scene in Cyrano de Bergerac, when for the first time he experiences the almost unbearable pleasure of speaking to his love in his own voice, and he declares, “Now let me die, having lived.” Keats longs to be “awake forever in a sweet unrest, / Still, still to hear her tender-taken breath, / And so live ever—or else swoon to death.”

When Keats returned from the Isle of Wight, he did not live again with Brown at Wentworth Place. He felt consumed by Fanny, and he feared that he would renounce his “sacred duty” to poetry and surrender his independence were he to live with her so near.

But, when in October he visited her, with Mrs. Dilke as a chaperone to help him control his feelings, he found himself again helpless.

His next letter to her is the most famous from their long correspondence, for reasons I hope will be obvious. My daughter Greta first shared this letter with me, saying that it is one of her favorite existing pieces of writing by any author, and that she reads it regularly.

My dearest Girl,

This moment I have set myself to copy some verses out fair. I cannot proceed with any degree of content. I must write you a line or two and see if that will assist in dismissing you from my Mind for ever so short a time. Upon my Soul I can think of nothing else. The time is passed when I had power to advise and warn you against the unpromising morning of my Life. My love has made me selfish. I cannot exist without you. I am forgetful of everything but seeing you again— my Life seems to stop there— I see no further. You have absorbed me. I have a sensation at the present moment as though I was dissolving— I should be exquisitely miserable without the hope of soon seeing you. I should be afraid to separate myself far from you. My sweet Fanny, will your heart never change? My love, will it? I have no limit now to my love—Your note came in just here—I cannot be happier away from you—’T is richer than an Argosy of Pearles. Do not threat me even in jest. I have been astonished that Men could die Martyrs for religion—I have shudder’d at it—I shudder no more. I could be martyr’d for my Religion—Love is my religion—I could die for that—I could die for you. My Creed is Love and you are its only tenet—You have ravish’d me away by a Power I cannot resist; and yet I could resist till I saw you; and even since I have seen you I have endeavoured often “to reason against the reasons of my Love.” I can do that no more—the pain would be too great—My Love is selfish. I cannot breathe without you.

Yours for ever

John Keats

He could die for her. He cannot breathe without her. He has the sensation as though he were dissolving. He is hers forever. This choice of words is agonizing to read, because we now know that Keats was experiencing signs of the tuberculosis that would claim his life in just a few short months after he wrote them. “Forever” would not be long.

Shortly after he sent this letter, Keats made a three-day visit to Wentworth, and after that, resolved to move back in with Brown, where Fanny would be next door. But though only a wall separated them, they would be separated by something far more grave.

One bitterly cold January night, he made the journey from Hampstead to London to see his brother George. A few days later, an infection went to his lungs. According to the memoirs of his friend Brown, when he returned to Wentworth Place, he was chilled and feverish, and Brown sent him to bed. Brown says,

On entering the cold sheets, before his head was on the pillow, he slightly coughed, and I heard him say,—“That is blood from my mouth.” I went towards him; he was examining a single drop of blood upon the sheet. “Bring me the candle, Brown, and let me see this blood.” After regarding it steadfastly he looked up in my face, with a calmness of countenance that I can never forget, and said,—-“I know the colour of that blood ; ——it is arterial blood ;—I cannot be deceived in that colour ;———that drop of blood is my death-warrant ;——I must die.”20

Thereafter, the barrier that separated him and Fanny was his illness, and the possibility of contagion. His room became a prison, from which he was tortured by the glimpses he could catch of Fanny as she roamed the garden outside his window. They could communicate only by letters slipped under the door. Biographer Roe says, “To have her living close by yet beyond his embrace was terrible, as day by day he glimpsed her in the garden, watched her coming and going, listened to her footfall and the sound of her voice.”21 He was denied any physical expression of his love. One day, Fanny presented him with a ring on which their names were engraved. Roe says, “He could not kiss her, but he would put his lips to their names.”

Keats was forced to accept that his grand ambitions in life and love would likely never be realized. He wrote in a letter to Reynolds, “I feel my body too weak to support me to the height; I am obliged continually to check myself and strive to be nothing,” and to Fanny, “My Mind has been the most discontented and restless one that ever was put into a body too small for it.”22 It is a theme reflected in one of his most famous poems, “When I Have Fears That I May Cease to Be.”

When I have fears that I may cease to be

Before my pen has gleaned my teeming brain,

Before high-pilèd books, in charactery,

Hold like rich garners the full ripened grain;

When I behold, upon the night’s starred face,

Huge cloudy symbols of a high romance,

And think that I may never live to trace

Their shadows with the magic hand of chance;

And when I feel, fair creature of an hour,

That I shall never look upon thee more,

Never have relish in the faery power

Of unreflecting love—then on the shore

Of the wide world I stand alone, and think

Till love and fame to nothingness do sink.

Keats’s friends took up a collection to send him to the warmer climate of Italy, where they believed he stood the best chance of recovery. His friend Joseph Severn would accompany him there. The time came for him to say good-bye to Fanny. She cut locks of his hair for herself and her sister. He asked her to write his sister and say she must avoid cold air. She gave him an oval of polished carnelian that he could hold and imagine her hand in his. And that night, she wrote in her diary just four words: “Mr. Keats left Hampstead.” I have to believe she was too thoroughly devastated to write anything more.

Keats’s health would not improve in Italy. We know of his final days from the memoir of Joseph Severn. I will spare you the agonizing details of his suffering, and tell you only that in a spiral of despair Keats contemplated suicide. He continually lamented his thwarted desires as a poet and a lover. He lay night after night in a deadly sweat, and one day, he turned to the visiting doctor and asked, “How long is this posthumous life of mine to last?”23 Severn reports that he would sometimes cry upon waking to find himself still alive. It was at this time that he gave Severn the instructions for his epitaph, which was to read only, “Here lies one whose name was writ in water.”

As death approached, Keats told Severn, “I can feel the cold earth upon me—the daisies growing over me—O for this quiet—it will be my first.”24 And on Friday, February 23, 1821, Keats said to his friend, “Severn—lift me up for I am dying—I shall die easy—don’t be frightened—thank God it has come.” Two days later his body was placed in a coffin, along with the unopened letters from Fanny that he couldn’t bear to read.

We need not worry, given Fanny’s abrupt diary entry on his departure, that she would be insensible to his death. She would later write to Keats’s sister:

No one but you can feel with me—all his friends have forgotten him, they have got over the first shock, and that with them is all. They think I have done the same, which I do not wonder at, for I [have] taken care never to trouble them with any feelings of mine, but I can tell you who next to me (I must say next to me) loved him best, that I have not got over it and never shall.25

She wore mourning for years and spent long nights walking along the Heath or reading Keats’s love letters.

Keats’s life was cruelly short and marred by tragedy, unrequited love, and ill health. But his frail body held a formidable soul. That soul lives on through his poetry and inspires us to make the most of our own opportunities for joy.

To relish those moments when we feel like some watcher of the skies when a new planet swims into its ken . . .

To strive to take the diamond drops, and treasure them. . . .

To savor all the sweets of song . . .

To know a friendship that makes us catch at the sound of footsteps on the gravelly floor . . .

To create for ourselves a rosy sanctuary with a wreathed trellis of the working brain. . . .

To show truth to flattered state, and whatever our circumstances, live free as the sky-searching lark . . .

To seek out the highest bliss of humankind, and flee to the haunts of nature with some kindred spirit . . .

To revere the Great Spirits now on earth sojourning, who give the world “another heart and other pulses” . . .

To know love that makes us long to live forever, or else swoon to death . . .

Keats was right to fear that, much too soon, he might cease to be. But his keen eye for beauty and meaning lives on. He himself once wrote, in the opening to Endymion,

A thing of beauty is a joy forever.

Its loveliness increases; it will never

Pass into nothingness; but still will keep

A bower quiet for us, and a sleep

Full of sweet dreams, and health, and quiet breathing.

Keats gave the world so many things of extraordinary beauty, quiet bowers where we can enjoy sweet dreams and health and quiet breathing, and I hope that there you have found and will continue to find joy of your own.

Click To Tweet

You might also like

Endnotes

1. Sidney Colvin, Keats (London: MacMillan and Co., Limited, 1909), 11–12.

2. Nicholas Roe, John Keats (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2012), 42.

3. Roe, John Keats, 40.

4. Roe, John Keats, 21.

5. Charles and Mary Cowden Clarke, “Recollections of Keats,” in Recollections of Writers (London: Sampson Low, Marston, Searle & Rivington, 1878), 122.

6. Roe, John Keats, 31.

7. John Keats, “Sonnet to Spenser,” Poem Hunter, https://www.poemhunter.com/poem/sonnet-to-spenser/ (accessed October 3, 2019).

8. John Keats, The Poetical Works of John Keats, edited by H. Buxton Forman (New York and Boston: Thomas Y. Crowell & Company, 1895), 40.

9. Roe, John Keats, 51.

10. John Keats, The Complete Works of John Keats, vol. 2, edited by H. Buxton Forman (New York: Thomas Y. Crowell & Co., 1900), 106.

11. Roe, John Keats, 83.

12. Roe, John Keats, 101.

13. Roe, John Keats, 205.

[14] Walter Jackson Bate, John Keats (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 1963), 501.

15. Stephen Hebron, “An Introduction to ‘Ode to a Nightingale,’” British Library, May 15, 2014, https://www.bl.uk/romantics-and-victorians/articles/an-introduction-to-ode-on-a-nightingale.

16. Roe, John Keats, 288.

17. Roe, John Keats, 330.

18. Roe, John Keats, 332.

19. Roe, John Keats, 331.

20. Colvin, Keats, 384.

21. Roe, John Keats, 362.

22. Roe, John Keats, 363.

23. The Life of John Keats (1795-1821)—Key Facts, Information & Biography, English History, https://englishhistory.net/keats/life/ (accessed October 3, 2019).

24. Roe, John Keats, 396.

25. Marie Adami, Fanny Keats (London: John Murray, 1937), 105–6.

![[TEST] The Objective Standard](https://test.theobjectivestandard.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/logo.png)