On April 5, 1839, Robert Smalls was born a slave in Beaufort, South Carolina. His “owner,” Henry McKee, hardly noticed; after all, it took years for a slave to become “useful.” Little did McKee know that Smalls would go on to become one of the greatest heroes of the Civil War—and to play an important role in rebuilding America afterward.

From the moment he could talk, it was evident that Smalls was different. McKee was “a relatively kind master, but nonetheless a master who had to be obeyed”—meaning, he allowed his slaves more autonomy than most of his peers did.1 From the age of five, Smalls tested these relatively lax boundaries, constantly asking questions about many topics—such as why black people were abused and forced to work. Many slaves were beaten or starved for asking such questions—even if they were children—but Smalls rarely found himself in serious trouble, probably due to a combination of several factors.

For one thing, Smalls’s charisma was powerful and apparent, especially by the time he was ten. He had a way of smiling, of speaking, and of making eye contact that conveyed sincerity and disarmed suspicious frowns. Sometime during his early teens, he was caught in the streets after curfew and arrested, but he managed to talk his way out of a whipping and was released into McKee’s custody with only a stern warning. Such light treatment of slaves caught outside after curfew was almost unheard of.2

McKee was well aware of Smalls’s ability to charm his way out of trouble, but for the most part he didn’t consider it a threat. He usually was content to let his slaves develop and express their own personalities, provided they finished their work, minded his orders, and committed no serious infractions. By the time Smalls was twelve or thirteen, McKee allowed him to work at restaurants and warehouses in the city and to keep a portion of his wages. (Most slave owners who hired out their slaves kept the entirety of their wages for themselves.) This small sliver of autonomy undoubtedly bolstered Smalls’s self-confidence and helped him to begin to think seriously about escaping slavery altogether.3

Smalls was also comparatively fortunate to have been born in a home that practiced the “task system” of slavery, as opposed to the far more brutal “gang system” common on large plantations. Under the task system, slaves were given to-do lists each day and were allowed to pursue their own activities with any extra time they had left afterward. Slaves forced to labor under the gang system were done when the overseer said they were done and were rarely permitted to do anything on their own behalves. Further, Smalls was a house slave, one who worked primarily indoors and rarely had to perform intense physical labor. He had four things that few other slaves had: money, free time, generally good health, and a relatively lenient master.4

Smalls’s mother, Lydia Polite, however, thought he had it too easy. She was no more content with her lot in life than most other slaves were, but she never seriously entertained any notions of changing it. In a way, she was fond of McKee and glad that he afforded her son extra privileges, but she worried that the special treatment would make him soft. It was fairly uncommon for a slave to serve the same family for his entire life; slaves were bought and sold frequently, and Smalls’s mother feared that his relaxed attitude and inquisitive nature would get him into serious trouble were he ever to be sold to another master.

Lydia’s solution was to deliberately expose her son to the evilest, most horrifying aspects of slavery. She took him into the city to witness an open-air slave auction, where people were beaten and tortured in the grueling summer heat for hours on end to show prospective buyers that the slaves could withstand such treatment and continue working. She then asked McKee to reassign her son to field work for a time so that he could see what other slaves had to endure. McKee refused at first but eventually granted her request and sent Smalls to the cotton fields for several weeks. Undoubtedly, his normal “job” seemed heavenly in comparison.5

Lydia thought that if Smalls were sufficiently shocked by what he experienced, he would become more demure and cautious. Her plan backfired. Enraged by the brutality with which other slaves were treated, he became more openly rebellious and confrontational. He quickly realized that he needed a long-range plan but wouldn’t be able to devise and execute one if he were sold or killed. Throughout the rest of his teens, he spent much of his free time thinking about how to free himself and his loved ones from bondage.

Around the age of fourteen, Smalls got a job as a longshoreman, then as a rigger, and later worked his way up to wheelman (a ship’s pilot), though slaves never were officially granted such title. He fell deeply in love with the sea and quickly took to a sailor’s lifestyle, exhibiting an undeniable talent for the work. He was such a skilled pilot that, within two years, he became the preferred choice when someone was needed to steer the ship through particularly shallow or dangerous waters.6

When Smalls was seventeen, he married Hannah Jones, a slave more than ten years his senior who already had two children of her own. Two years later, he fathered a third with her, a daughter they named Elizabeth. By then, Smalls had saved more than $100, the equivalent of $3,025 in 2020—nearly enough to buy his own freedom legally.7 But he was unwilling to buy himself out of slavery unless he could afford to bring his entire family with him. Smalls openly approached Samuel Kingman (Hannah’s “owner”), who set a high price of $800 for Hannah and Elizabeth. It was an amount within Smalls’s power to accrue, but it would take decades and wouldn’t include his own freedom, his mother’s, or that of Hannah’s other children. Smalls feigned gratitude for the “offer” but never seriously considered it.8

The first shots of the Civil War were fired in April 1861 at Fort Sumter, just a few miles from Charleston, where Smalls lived and worked. He was twenty-three at the time and for several years had been working aboard the Planter, a Confederate military cargo ship. Although the war would inflict unimaginable death and destruction on innumerable slaves and free Americans, it also brought a certain kind of opportunity.

Previously, one of Smalls’s biggest unsolved problems was how to get far enough north to ensure that he wouldn’t be recaptured. Were he traveling alone, an overland journey would be perilous but doable; with his aging mother and young children in tow, it would be nearly impossible. The war now underway, Union troops patrolled far into the South, and given that one of Congress’s 1862 articles of war required them to aid and protect escaped slaves, Smalls had the opening he’d been waiting for.

All he needed to do was to make contact with Union soldiers—still a tall order but much easier than escaping the South on his own. He spent months trying to formulate an escape plan but found it difficult because he didn’t know when or in what form an opportunity might present itself. So he decided to create his own opportunity—by stealing the Planter, one of the fastest ships in the area.

The Planter, Wikiwand.com

He had four major obstacles to overcome. Most obviously, he needed a way to steal the ship without its owners noticing until Smalls and his entourage were well out of cannon range, which, given the placement of Confederate forts, would take several hours. Furthermore, it was impossible to pilot the Planter alone, so he would need the cooperation of most of the other crewmen. The would-be escapees also had to figure out how to sail past four heavily armed Confederate forts without raising an alarm—and how to approach the Union ships blockading Charleston, in a Confederate military vessel, without being blown out of the water.

This exceedingly dangerous plan could fail in countless ways. The Planter had two small deck guns but would never stand a chance in a fight with combat ships or against the massive cannons in the forts. If anyone in Charleston noticed the ship missing, they would immediately deduce what had happened and send word to the forts. To make matters worse, not all of the slaves whom Smalls needed for his plan were willing accomplices: Two men revealed their intent to tell the ship’s owners about the escape plan and were silenced only when Smalls threatened them with death.9

Smalls had at least one detail figured out: A simple straw hat would get them safely past the Confederate forts and checkpoints. Charles Relyea, the Planter’s captain, frequently wore a unique wide-brimmed hat, and other Confederate officers in the Charleston area had come to recognize it at a distance. Smalls and Relyea were roughly the same size and had vaguely similar complexions—Relyea was dark-skinned for a white man, and Smalls was light-skinned for a black man. Smalls had served on the Planter for years and had watched Relyea carefully during that time; as a result, he knew all of the Confederate hand signals needed to pass each checkpoint. Smalls could never pass for Relyea in broad daylight, but he could do so at a distance and under cover of darkness.10

He had yet another variable to account for. Smalls intended to escape not only with his own family but also with the families of several of the other crewmen. Families occasionally were permitted to visit their men aboard the vessels on which they served, but only under strict supervision. Smalls had no way to get all of them aboard in Charleston and to conceal their presence until after curfew. They would have to be picked up somewhere between there and Fort Sumter.

Coordinating the pickup on short notice would be a difficult logistical challenge. When Smalls judged the time to be right, someone from aboard the Planter would have to go ashore, travel to each family, and tell them where to go. Each family would then have to escape their masters undetected and reach the pickup point with great haste. Smalls soon realized that this plan, too, was not feasible—it could go wrong in too many ways.

On May 13, 1862, a combination of good fortune and quick thinking rendered such coordination unnecessary. The crew of the Planter had just finished a grueling two-week job disassembling heavy cannons and storing them on the ship to be transported elsewhere. The ship’s three white officers were tired but in high spirits. They told the black men that they would be spending the night ashore, as they had occasionally before. This meant that the crew would be unsupervised aboard the Planter all night. Smalls almost couldn’t believe his luck when he saw that Relyea had even left his hat in the ship’s wheelhouse.

Taking advantage of the officers’ good moods, Smalls and another man asked if their families might be permitted to visit them that evening. The officers agreed on the usual condition that the women and children return home before curfew. Smalls wouldn’t dare try to leave Charleston with all of the family members aboard—soldiers patrolling the pier would be watching them carefully before the curfew bell rang at ten o’clock—but at least he now had a way to communicate with all of them at once in a manner that wouldn’t arouse suspicion.

When the families arrived, the men told them of the plan. This was the first that the women and children had heard of it, although Smalls recently had told Hannah. She had known that Smalls longed to escape but hadn’t realized that he was formulating a plan and intended to execute it. She was taken aback but quickly regained her composure and told him, “It is a risk, dear, but you and I, and our little ones must be free. I will go, for where you die, I will die.”11

The other women were less steadfast. They cried and screamed when they learned what they had stumbled into, and the men struggled to quiet them. Fortunately, no one ashore heard the commotion. Eventually, Smalls locked the most hysterical of the women in a cabin and even threatened them with death should they compromise the plan. Later, once the shock had worn off, those women admitted that they were glad for the chance at freedom and forgave Smalls for threatening them.12

Once the women had calmed down, Smalls sent them ashore with three crewmen who pretended to be escorting them back home. After the group was out of sight of the patrolling soldiers, they circled around to another ship docked several miles away, the Etiwan, which one of the crewmen knew to be attended that night only by slaves. He persuaded one of the Etiwan’s crew to allow the women and children to hide aboard the ship until the Planter came to pick them up later that night.13

When the three men returned to the Planter, the chance to escape was as good as it ever would be. The crew had the ship, a pickup location, and Relyea’s hat. All they had to do was sail casually (but not too casually) past four Confederate strongholds, slip past other military ships without raising suspicion, avoid being sunk by the Union navy, and hope that no one in Charleston noticed for several hours that the Planter was missing.

Smalls needed to time their departure precisely. It was imperative that they pass all four checkpoints before sunrise, while it was still dark enough for Smalls to be mistaken for Relyea. Yet they needed to reach the Union fleet after sunrise so that the heavily armed warships would be able to see the Planter’s white flag and refrain from firing on them. The window for success was frighteningly narrow—a matter of minutes. Fortunately, Smalls knew both the Planter and the surrounding waterways like the back of his hand and had a good idea of how long it would take to reach the Union blockade.

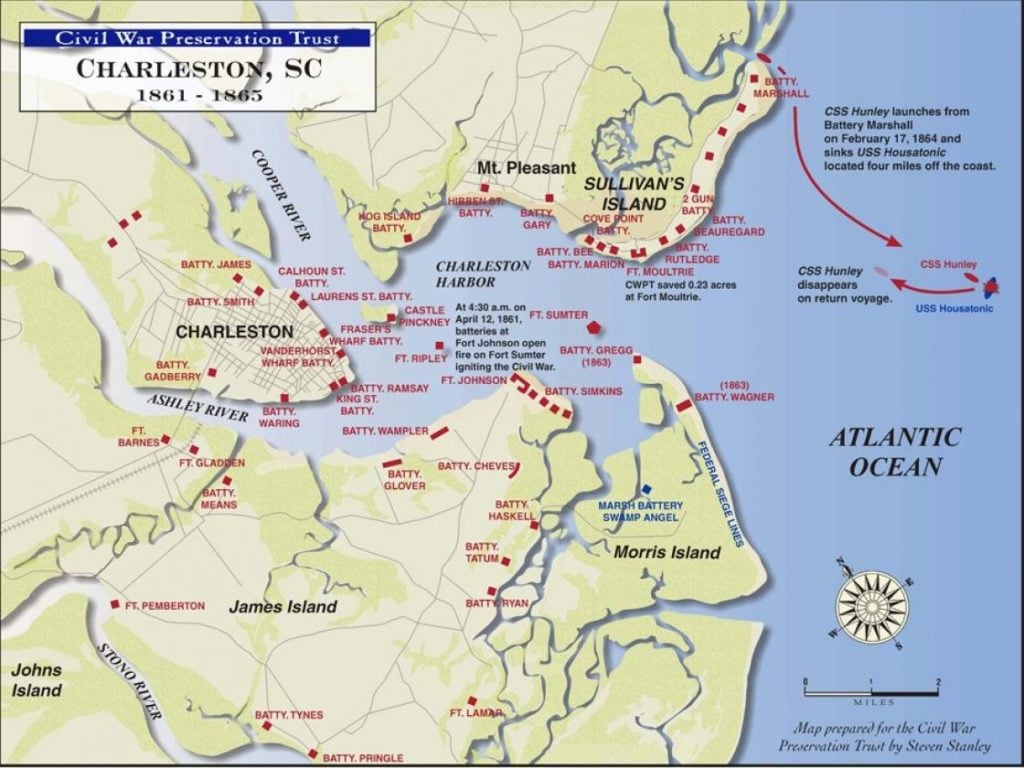

Map of Confederate checkpoints and gun batteries in the Charleston harbor, 1861, Civil War Preservation Trust.

Sometime around 3 a.m., Smalls judged the time to be right. He waited for the pier guards to walk out of sight, donned Relyea’s hat, and ordered the Planter to cast off. All of the passengers held their breath because their initial direction of travel was suspicious. They were headed northeast to rendezvous with the Etiwan, but the Planter almost always sailed southeast when it left the pier. They expected alarms to sound at any moment, but the night remained quiet. The Planter passed another Confederate ship en route to the Etiwan—so closely that Smalls was sure that their cover would be blown. An officer on the other ship watched Smalls for a long time but finally seemed to decide that nothing was amiss and went about his business. The crew soon retrieved their families from the Etiwan without incident.14

Now carrying sixteen people, the Planter turned toward Castle Pinckney, the first checkpoint that it would have to pass on its way out to sea. Smalls gave the appropriate hand signals, and the fort flashed the “clear to proceed” signal in response. The next two forts also allowed the Planter to pass, but as the nearly-free slaves approached Fort Sumter, their apprehension began to grow. It was the most heavily armed of the forts and tended to be manned by the most suspicious soldiers. One of the men aboard later said, “When we drew near the fort every man but Robert Smalls felt his knees giving way and the women began crying and praying again.”15

As the Planter approached the fort, several men urged Smalls to give it a wide berth. Smalls refused, saying that such behavior would almost certainly arouse suspicion. He steered the ship along its normal path, slowly, as though he were merely enjoying the early morning air and in no particular hurry. When Fort Sumter flashed the challenge signal, Smalls again gave the correct hand signs. There was a long pause. The fort didn’t immediately respond, and Smalls now expected cannon fire to shred the Planter at any moment. Finally, the fort signaled that all was well, and Smalls sailed his ship out of the harbor.16

Within a few minutes, soldiers at Fort Sumter raised an alarm when the Planter did not turn toward Morris Island but, instead, sailed directly for the Union ships several miles farther out to sea. The Confederates knew better than to waste ammunition. Smalls and his compatriots were well out of range. No Confederate vessel would be able to catch the Planter before it reached the safety of the blockade line.

The men aboard the Planter quickly worked to take down the ship’s Confederate and South Carolina flags and to raise a white flag of surrender (actually, a dirty bed sheet). The sun was just minutes from rising, and the stolen ship was quickly approaching the Onward, a massive Union warship. Its captain, a man by the name of Nickels, ordered his men to ready the cannons and to fire on the Planter at his command. With the first rays of dawn just beginning to shine over the horizon, Nickels was only seconds from ordering his men to fire when he noticed the dirty white flag; instead, he gave the order to stand down. One of the men under Nickels’s command later wrote:

Just as No. 3 port gun was being elevated, someone cried out, “I see something that looks like a white flag;” and true enough there was something flying on the steamer that would have been white by application of soap and water. As she neared us, we looked in vain for the face of a white man. When they discovered that we would not fire on them, there was a rush of contrabands out on her deck, some dancing, some singing, whistling, jumping; and others stood looking towards Fort Sumter, and muttering all sorts of maledictions against it, and “de heart of de Souf,” generally. As the steamer came near, and under the stern of the Onward, one of the Colored men stepped forward, and taking off his hat, shouted, “Good morning, sir! I’ve brought you some of the old United States guns, sir!”17

That man, of course, was Robert Smalls. The Union sailors were shocked, but also delighted and amused, to learn that sixteen escaped slaves had delivered to them a veritable treasure trove of military hardware. Nickels arranged for the USS Augusta to escort the Planter sixty miles south so that Smalls could meet with Commodore Samuel Francis Du Pont. Smalls initially was confused as to why Nickels would want him to meet Du Pont, but the reason would soon be clear.18

Du Pont was a stern but compassionate man, a seasoned sailor, and a decorated soldier. For most of his adult life, he had “been morally opposed to the peculiar institution [of slavery] . . . but he, like many others, also believed that the Constitution allowed for it.”19 He had been under the impression that most slaves were treated well by their owners and were afforded many freedoms. However, his view of the “peculiar institution” changed radically when he captured Southern plantations during the early days of the Civil War:

“My ideas have undergone great change as to the condition of the slaves since I came here and have been on the plantations,” [Du Pont] wrote to his wife a few weeks after arriving [in Port Royal, South Carolina]. “But God forgive me—I have seen nothing that has disgusted me more than the wretched physical wants of these poor people, who earn all the gold spent by their masters at Saratoga and in Europe. No wonder they stand shooting down rather than go back with their owners.”20

Nickels knew that Du Pont had developed deep empathy for slaves, as well as a heartfelt desire to help them secure their own freedom. Du Pont was impressed with both Smalls and the Planter, and the two men talked late into the evening about the escape that Smalls had engineered. Smalls shared detailed Confederate military intelligence with Du Pont, and the heavy cannons he had delivered to the Union were extremely valuable. The following morning, Du Pont wrote of Smalls in a message to the secretary of the navy:

This man, Robert Smalls, is superior to any who has yet come into the lines, intelligent as many of them have been. His information has been most interesting, and portions of it of the utmost importance. I shall continue to employ Robert as a pilot on board the Planter for inland waters.21

Du Pont made good on his promise, and Smalls gladly accepted his offer, along with a share of the federal bounty for capturing the Planter ($1,500, which was more than ten times what Smalls had saved during his entire life). He was then assigned to the Charleston area, where his detailed knowledge of the locations of Confederate mines proved invaluable.22

A few months later, Smalls went to Washington, D.C., along with Rev. Mansfield French, a Methodist minister who devoted much of his time to helping former slaves in Port Royal. The two of them sought to persuade President Lincoln and Secretary of War Edwin Stanton to allow them to recruit escaped slaves to fight for the Union. They were successful; Stanton signed an order allowing up to five thousand former slaves to enlist at Port Royal.23

Smalls would, by his own account, go on to participate in a total of seventeen land and sea battles throughout the remainder of the war. He also piloted at least a dozen ships, ranging from light transports to massively armored warships. In 1863, the captain of the Planter fled in panic when the ship came under attack from Confederate guns. Smalls assumed command and piloted the ship to safety, saving the entire crew. For that act of bravery, he was promoted to acting captain of the Planter despite still being classified as a civilian contractor. This also made him the first black American ever placed in charge of a military ship.24

The following year, Smalls piloted the Planter up the Savannah river in Georgia to support William Tecumseh Sherman at the tail end of his scorched-earth campaign, which was instrumental in bringing the war to a close. The year after that, in April 1865, Smalls and his trusty ship returned to Fort Sumter in Charleston for the raising of the American flag—a ceremony that marked the official end of the Civil War, in the same place where it had begun.25

Smalls resigned from military service a few months later. He continued to pilot the Planter in service of the Freedmen’s Bureau, a subdivision of the U.S. Department of War, which undertook humanitarian aid missions to provide food, clothing, and medicine to recently freed slaves. Shortly after the end of the war, he returned to Beaufort, South Carolina—and purchased the home of his former master, which had been seized by the federal government two years earlier. McKee sued Smalls in an attempt to regain ownership of the house, but Smalls was victorious in court and retained possession of it. He and his family lived in the house for the remainder of their lives.26

Smalls's house in Beaufort, SC, South Carolina Board of Tourism

Although Smalls was retired from military life, he still had much to achieve. Shortly after moving into the former McKee home, he purchased a two-story building in Beaufort and converted it into a private school for black children. Around that time, he also learned how to read and write. In 1866, he teamed up with Richard Howell Gleaves, a businessman from Philadelphia, to open a general store in Beaufort. He also invested heavily in the local economy, became a partner and cofounder of the Enterprise Railroad, and started a black-owned newspaper, the Beaufort Southern Standard.27

In 1874, Smalls was elected to the House of Representatives, where he served a total of five terms. During that time, he introduced and worked to pass the Homestead Act and contributed significantly to the Civil Rights Act of 1866. In 1913, he used his political influence (and a calculated bluff) to stop a lynching in Beaufort.28

Two years later, in 1915, Smalls died at the age of seventy-five of complications resulting from malaria and diabetes. He was buried in a churchyard in Beaufort, alongside Hannah, who had died in 1883, and his second wife, Annie Wigg, who died in 1895. His tombstone bears an inscription taken from a statement he made to the South Carolina legislature twenty years earlier: “My race needs no special defense, for the past history of them in this country proves them to be the equal of any people anywhere. All they need is an equal chance in the battle of life.”29

Robert Smalls had much in common with many other heroes of history, such as Joan of Arc and Rosa Parks. Like them, Smalls refused to live as a victim. His daring escape aboard the Planter was nothing short of incredible. That alone was enough to earn him the title of “hero,” but he chose to continue fighting for others’ freedom after he’d achieved it for himself. After the war, he grew his moderate wealth into a small fortune by rebuilding destroyed towns and investing in businesses. He also fought for blacks’ rights in Washington, which helped to pave the way for ever-greater personal and economic freedom in the South. Smalls relished life and all it had to offer with a passion that, sadly, most people never attain—and he did so wearing many different hats (not only Relyea’s). He was, in every sense of the phrase, an American hero.

Click To Tweet

You might also like

Endnotes

1. Cate Lineberry, Be Free or Die: The Amazing Story of Robert Smalls’ Escape from Slavery to Union Hero (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2017), 32.

2. Lineberry, Be Free or Die, 40.

3. Lineberry, Be Free or Die, 44.

4. Lineberry, Be Free or Die, 35.

5. Lineberry, Be Free or Die, 39.

6. Lineberry, Be Free or Die, 56–57.

7. “Freedom” is a relative term here. In South Carolina at the time, a small percentage of blacks were “free” but only in certain respects. Their rights were recognized and protected by the government to a limited extent, but they were still second-class citizens in many ways.

8. Lineberry, Be Free or Die, 47.

9. Lineberry, Be Free or Die, 15.

10. Lucas Reilly, “Robert Smalls: The Slave Who Stole a Confederate Warship and Became a Congressman,” Mental Floss, February 12, 2019, https://www.mentalfloss.com/article/91630/robert-smalls-slave-who-stole-confederate-warship-and-became-congressman; Lineberry, Be Free or Die, 12.

11. Lineberry, Be Free or Die, 13.

12. Lineberry, Be Free or Die, 19.

13. PBS, “Robert Smalls: A Daring Escape,” November 5, 2013, https://www.pbs.org/video/african-americans-many-rivers-cross-robert-smalls-daring-escape/.

14. Lineberry, Be Free or Die, 22.

15. Lineberry, Be Free or Die, 24.

16. Lineberry, Be Free or Die, 24–25.

17. “Contrabands” was a term often used by Northerners to refer to escaped slaves; Henry Louis Gates Jr., “Which Slave Sailed Himself to Freedom?,” PBS, http://www.pbs.org/wnet/african-americans-many-rivers-to-cross/history/which-slave-sailed-himself-to-freedom/ (accessed January 23, 2020).

18. Lineberry, Be Free or Die, 77.

19. Lineberry, Be Free or Die, 77–78.

20. Lineberry, Be Free or Die, 77–78.

21. Lineberry, Be Free or Die, 80.

22. Lineberry, Be Free or Die, 80.

23. Howard Westwood, Black Troops, White Commanders and Freedmen During the Civil War (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1991), 74–85.

24. Gerald S. Henig, “The Unstoppable Mr. Smalls,” HistoryNet, https://www.historynet.com/unstoppable-mr-smalls.htm (accessed January 23, 2020).

25. Westwood, Black Troops, White Commanders and Freedmen, 85.

26. Lineberry, Be Free or Die, 209–10.

27. Catherine Reef, African Americans in the Military (New York: Infobase Publishing, 2014), 184–86.

28. Stanley Turkel, Heroes of the American Reconstruction: Profiles of Sixteen Educators, Politicians and Activists (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2005), 139. When Smalls learned that two black men were about to be lynched by an angry mob, he confronted the mob’s leader and told him that he’d positioned black “operatives” all over town who had been instructed to burn it to the ground if the lynching weren’t stopped. No part of that was true, but the mob’s leader believed Smalls and called off the lynching.

29. “He Sunk the Rebel Rag, My Boys, Hurrah for Robert Smalls,” Daily Kos, July 16, 2019, https://www.dailykos.com/stories/2019/7/16/1870630/-He-sunk-the-rebel-rag-my-boys-Hurrah-for-Robert-Smalls.

![[TEST] The Objective Standard](https://test.theobjectivestandard.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/logo.png)