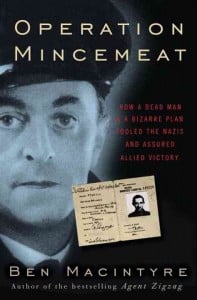

Operation Mincemeat: How a Dead Man and a Bizarre Plan Fooled the Nazis and Assured an Allied Victory, by Ben Macintyre. New York: Crown, 2010. 416 pp. $25.99 (hardcover).

In 1943, on the coast of Andalusia in southwest Spain, a dead man “washed ashore wearing a fake uniform and the underwear of a dead Oxford don, with a love letter from a girl he had never known pressed to his long-dead heart” (pp. 323–24). It was near the high point of the Third Reich’s reign, with Europe effectively under Nazi control; but, owing in part to this dead man, Hitler’s days were numbered.

Ben Macintyre tells the story of this fantastic ruse in Operation Mincemeat: How a Dead Man and a Bizarre Plan Fooled the Nazis and Assured an Allied Victory. The book may read like fiction, but remarkably, the story is completely true.

It begins during World War II when the Nazi war machine “was at last beginning to stutter and misfire.”

The British Eighth Army under Montgomery had vanquished Rommel’s invincible Afrika Korps at El Alamein. The Allied invasion of Morocco and Tunisia had fatally weakened Germany’s grip, and with the liberation of Tunis, the Allies would control the coast of North Africa, its ports and airfields, from Casablanca to Alexandria. The time had come to lay siege to Hitler’s Fortress [across Europe]. But where?

Sicily was the logical place from which to deliver the gut punch into what Churchill famously called the soft “underbelly of the Axis.” The island at the toe of Italy’s boot commanded the channel linking the two sides of the Mediterranean, just eighty miles from the Tunisian coast. . . . The British in Malta and Allied convoys had been pummeled by Luftwaffe bombers taking off from the island, and . . . “no major operation could be launched, maintained, or supplied until the enemy airfields and other bases in Sicily had been obliterated so as to allow free passage through the Mediterranean.”

An invasion of Sicily would open the road to Rome . . . allow for preparations to invade France, and perhaps knock a tottering Italy out of the war. . . . [Thus]: Sicily would be the target, the precursor to the invasion of mainland Europe. (pp. 36–37)

There was a major problem, however. Macintyre points out that the strategic importance of Sicily was as clear to the Nazis as it was to the Allies and that, if the Nazis were prepared for it, an invasion would be a bloodbath. So how could the Allies catch their enemy off guard?

The solution was to launch what Macintyre calls one of the most extraordinary deception operations ever attempted. The British Secret Service would take a dead man and plant on him fake documents that suggested that the Allies were planning to bomb Sicily only as an initial feint preceding an attack on Nazi forces in Greece and Sardinia. They would then float their man near the Spanish coastline, making it appear as though he drowned at sea, and hope that one of the many Nazi spies in Spain discovered him and the documents and passed their content along to his superiors—convincing them to weaken Sicily by moving forces to Greece and Sardinia.

In the same style and with the same joyful sense of humor that brought his earlier book Agent ZigZag so much acclaim, Macintyre takes readers into the heart of this operation, introducing each of the oddball characters who contributed to it and demonstrating the hilarity of the ruse. For example, Macintryre says that the masterminds of the plan, Charles Cholmondeley and Ewen Montagu, “sought to arrange everything before obtaining final approval . . . on the assumption that senior officers were far less likely to meddle when presented with a fait very nearly accompli” (p. 116). He titles a chapter focused on the painstaking detail with which the book’s heroes wrote their dead corpse a fake identity “A Novel Approach.” And he reports his subjects saying all sorts of interesting things—such as a coroner joking to other characters that an alternative means of them getting to his mortuary is “to get run over” (p. 45).

Perhaps the most striking aspect of Macintyre’s style is his ability to describe characters in colorful ways. Consider, for instance, his description of Cholmondeley:

Cholmondeley gazed at the world through thick, round spectacles, from behind a remarkable mustache fully six inches long and waxed into magnificent points. Over six feet three inches tall, with size twelve feet, he never quite seemed to fit his uniform and walked with a strange, loping gait, “lifting his toes as he walked.” (p. 16)

Although Macintyre’s style adds to the entertainment value of Operation Mincemeat, the story itself is truly captivating. Cholmondeley and Montagu had difficulty obtaining a dead body, as people “tended to be killed, or to kill themselves, in all the wrong ways” (p. 40). They had to figure out how to keep the dead body “fresh,” make a picture for his ID card in which he did not look so unmistakably dead, and so on.

The biggest obstacle was the creation of the false letters that the Germans would read. Macintyre frames the difficulty: “If the faked intelligence was too obvious, the Germans would spot the hoax; if it was too subtle, they might miss the clues altogether. At what level should the disinformation be pitched?” (p. 97). Given such conflicting orders, “Draft after draft was proposed by Montagu and Cholmondeley, revised by more senior officers and committees, scrawled over, retyped, sent off for approval, and then modified, amended, rejected, and rewritten all over again” (p. 116). The matter was finally resolved when the official they were all trying to please sat down and wrote a surprisingly ideal letter where the false targets were “not blatantly mentioned although very clearly indicated” (p. 118).

But even after everything was written, and the body successfully washed ashore, the job of the British Secret Service was not done. Macintyre indicates how the British had to show concern for getting the corpse back without anyone searching through the documents he carried, while at the same time delaying the corpse’s return so that Nazi spies had time to copy and transmit the information. He also analyzes the spies who worked for the Nazis, showing how their various characteristics and motivations worked to the advantage of the ruse. These and other fascinating details combine to deliver a high-level drama.

Throughout Operation Mincemeat, there is always the danger of something going wrong—of the actual cause of death being determined, of an inconsistency in the letters being identified, of the fake intelligence being handed back to England before spies can pass it on to Germany, or of someone in the Nazi government being both smart enough to see through the ruse and brave enough to say so to his boss. Thankfully, as regards that last potentiality, and as Macintyre puts it, “The men surrounding Hitler were not made of such stuff” (p. 254).

In the end, the operation fooled Hitler himself, who ordered a battle-hardened division to move from Sicily to Greece. As a result, the imaginative minds of Cholmondeley and Montagu saved countless lives in the victorious Allied attack on Sicily.

Unfortunately, the credits for Operation Mincemeat seem to roll forever. Macintyre tells us what happened to all the characters after the war and he tells what a host of officers, generals, politicians, and historians thought of the operation. On the one hand, that applause is annoyingly long and at times repetitive. On the other, there is no doubt the heroes of this story deserve such recognition. Macintyre has told their story well.

![[TEST] The Objective Standard](https://test.theobjectivestandard.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/logo.png)