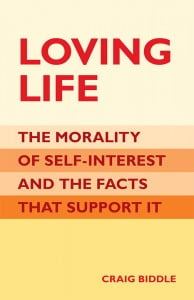

Author’s note: This is Chapter 1 of my book Loving Life: The Morality of Self-Interest and the Facts that Support It (Richmond: Glen Allen Press, 2002). The book is an introduction to Ayn Rand’s morality of rational egoism.

“If there is no God, anything goes.” This popular claim is an eloquent distillation of a deep-rooted false alternative wreaking havoc on human life and happiness. The adage compresses into a few words the age-old debate over whether morality is a matter of “divine commandments” or “human sentiments.” Whatever their disagreements, both sides of this argument accept the idea that your basic moral choice is to be guided either by faith or by feelings. In other words, both sides agree that your choice is: religion or subjectivism. But if you want to live and enjoy life, neither of these will do. Neither religion nor subjectivism provides proper guidance for human action; each calls for human sacrifice and leads to human suffering—both physical and spiritual. To see why, we will look first at the theoretical essence of each of these doctrines; then we will turn to the practical consequences—historical and personal—of accepting them.

Let us begin with religion.

Religion holds that there is a God who demands your faith and obedience. He is said to be an all-powerful, all-knowing, all-good being who is the creator of the universe, the source of all truth, and the maker of moral law. Religion’s basic moral tenet is: Don’t place your self, your personal values, your own interests, your will, above those of God. Rather, you should live to glorify Him, to obey His commands, to fulfill His higher purpose. To do otherwise—to act on behalf of your own selfish concerns as if your life were an end in itself—is to “sin.” As the religious scholar Reverend John Stott declares: “God’s order is that we put him first, others next, self last. Sin is the reversal of the order.”1

According to religion, being moral consists not in pursuing your own interests, but in self-sacrificially serving God. Theologian and rabbi Abraham Heschel expresses this tenet as follows: “The essence and greatness of man do not lie in his ability to please his ego, to satisfy his needs, but rather in his ability to stand above his ego, to ignore his own needs; to sacrifice his own interests for the sake of the holy.”2

Now, you might argue that to ignore your own needs and sacrifice your own interests is contrary to the requirements of your life and happiness. But according to religion, that is no ground for complaint, because, as theologian Walter Kaiser puts it: “God has the right to require human sacrifice.”3

Disturbed by such an assertion, you might ask: What about God’s love for man? If God loves us, why would he call for us to sacrifice? To which Dr. Stott answers: “Self-sacrifice is what the Bible means by ‘love.’”4

Taking yet another angle, you might argue that self-sacrifice leads to suffering. But this fact is no ground for complaint either, because, according to the Bible, Adam disobeyed God by eating some forbidden fruit; therefore, you and I and all of Adam’s descendents deserve to suffer.5 As Saint Augustine put it: “We are suffering the just retribution of the omnipotent God. It is because it was to Him that we [by way of Adam] refused our obedience and our service that our body, which used to be obedient, now troubles us by its insubordination.”6

The “insubordination” to which Augustine refers has to do with the aversion many people have to ignoring their own needs and sacrificing their own interests. After all, self-sacrifice can be extremely painful, both physically and spiritually. It can even be fatal. But, according to religion, if God tells a person to do something, the person is morally obligated to do it—regardless of the difficulties or consequences involved.

For a biblical example of what such obedience can mean in practice, consider the case of Abraham and Isaac. According to the story, God told Abraham: “Take your son, your only son Isaac, whom you love, and go to the land of Moriah, and sacrifice him there as a burnt offering.”7 Needless to say, it would be very painful for a man to kill his son, whom he loves. Nevertheless, because Abraham was faithfully committed to obeying the will of God, he set out to do just that.

Was Abraham’s choice moral? Should he have done it? Would you do it? What do religionists say about this? According to Saint Augustine: “The obedience of Abraham is rightly regarded as magnificent precisely because the killing of his son was a command so difficult to obey. . . .”8

Magnificent?

As shocking as Augustine’s position may be, it is the only stance a dedicated religionist can take on the issue, because the only alternative is to challenge the alleged authority of God, and that is the cardinal religious no-no. “Above all,” writes the devoutly religious René Descartes, reminding us of the applicable tenet, “we ought to submit to the Divine authority rather than to our own judgment even though the light of reason may seem to us to suggest, with the utmost clearness and evidence, something opposite.”9

According to religion, God’s will, however objectionable, is by definition good; and human judgment to the contrary, however rational, is by definition bad. The “real distinction between right and wrong,” explains Bishop Robert Mortimer, “is independent of what we happen to think. It is rooted in the nature and will of God.”

When a man’s conscience tells him that a thing is right, which is in fact what God wills, his conscience is true and its judgment correct; when a man’s conscience tells him a thing is right which is, in fact, contrary to God’s will, his conscience is false and telling him a lie.10

Thus, if God wills that a man should kill his son, then, regardless of what the man thinks, he should do it.

But, you might ask, isn’t human sacrifice wrong on principle? Not according to religion. As Dr. Kaiser reminds us, the religious point of view is precisely that “human sacrifice cannot be condemned on principle. The truth is that God owns all life and has a right to give or take it as he wills. To reject on all grounds God’s legitimate right to ask for life under any conditions would be to remove his sovereignty and question his justice. . . .”11 Bishop Mortimer elaborates the religious position as follows:

[God] has an absolute claim on our obedience. We do not exist in our own right, but only as His creatures, who ought therefore to do and be what He desires. We do not possess anything in the world, absolutely, not even our own bodies; we hold things in trust for God, who created them, and are bound, therefore, to use them only as He intends that they should be used.12

In short, the basic moral tenet of religion is that obedience to God must be absolute—calls for human sacrifice and all.

Granted, religion does not call for everyone to murder his child. But it does call for everyone to sacrifice his judgment and interests for the sake of an alleged God; and in order to uphold this tenet consistently, a person must be willing to do just that. If he claims to accept the moral tenets of religion but fails to uphold them consistently, then, on his own terms, he is guilty of “sin”—and on anyone’s terms, he is guilty of hypocrisy (the consequences of which we will get to shortly).

Granted, religion does not call for everyone to murder his child. But it does call for everyone to sacrifice his judgment and interests for the sake of an alleged God; and in order to uphold this tenet consistently, a person must be willing to do just that. If he claims to accept the moral tenets of religion but fails to uphold them consistently, then, on his own terms, he is guilty of “sin”—and on anyone’s terms, he is guilty of hypocrisy (the consequences of which we will get to shortly).

Given the sacrificial nature of religion, it is not surprising that many people reject it and embrace its alleged opposite: subjectivism. But if human sacrifice is the problem, subjectivism is no solution.

Whereas religion holds that God creates truth and moral law, subjectivism holds that people do; it is the view that truth and morality are not objective, but “subjective”—not discovered by the human mind, but created by it. This creed comes in several varieties, two of which are: personal subjectivism and social subjectivism.

Personal subjectivism is the idea that truth and morality are creations of the mind of the individual—or matters of personal opinion. Social subjectivism is the notion that truth and morality are creations of the mind of a collective (a group of people)—or matters of social convention. Personal subjectivism has been around for thousands of years; its father was Protagoras of ancient Greece.13 Social subjectivism was born in the late eighteenth century; its father was the German philosopher Immanuel Kant.14

These two versions of subjectivism have been accepted over the years in varying degrees and with numerous twists. What is important for our present purpose is that, in some form or another, the notion that people create (rather than discover) truth and morality has been prevalent among intellectuals for almost a century. As sociologist Michael Schudson notes: “From the 1920s on, the idea that human beings individually and collectively construct the reality they deal with has held a central position in social thought.”15 And the dominant views on morality have been shaped accordingly. Let us look first at the ethics of social subjectivism.

Social subjectivism holds that truth and morality are matters of social convention. As Stanford professor Richard Rorty puts it: “There’s no court of appeal higher than a democratic consensus.”16 In other words: The will of the majority determines what’s true and what’s right.17 Social subjectivism’s basic moral tenet is: Don’t place your self, your independent judgment, your personal values, your selfish concerns, above those of the group or the “common good.” Rather, you should subordinate your own thoughts and interests to the beliefs, needs, and desires of the “whole”—of which you are merely a “part.”

On this view, being moral consists in pursuing not your own well-being and happiness, but the “greater” well-being and happiness of the group or collective. Your life is not an end in itself, but a means to the ends of society; thus, you should make personal sacrifices for society’s “greater good.” To do otherwise—to pursue your own selfish goals in disregard of the “collective will”—is to be immoral.

Note that the moral common denominator of religion and social subjectivism is altruism: the theory that being moral consists in self-sacrificially serving others. (Alter is Latin for other; “altruism” literally means “other-ism.”) According to altruism, self-sacrifice for the sake of others is the standard of morality. Thus, as philosophy professor Louis Pojman acknowledges, “complete altruism” means “total self-effacement for the sake of others.”18 While the general theory does not specify which particular others you should sacrifice for, both religion and social subjectivism are quick to fill in the blank: Religion says the significant other is “God”; social subjectivism says it is “society.” Religion says you should sacrifice for the sake of the “holy”; social subjectivism says you should sacrifice for the sake of the “whole.”

In one form or another, altruism is the generally accepted and propagated morality today. By and large, people equate “doing the rightthing” with “selflessly doing things for others.” Mother Teresa and Peace Corps types are regarded as paragons of virtue; selflessness is considered the mark of morality.

For a homey example of the ethics of social subjectivism, consider the widespread “volunteerism” or “community service” crusade. Presidents Clinton, Carter, Ford, Bush Sr., Bush Jr., General Colin Powell, Oprah Winfrey, Nancy Reagan, Alan Keyes, William F. Buckley, and so on—liberals, moderates, and conservatives alike—have all joined hands to advocate this so-called ideal. Why? What brings this unlikely crew together? The mutually accepted and unchallenged premise that people have a moral duty to serve others.

“Citizen service is the main way we recognize that we are responsible for one another,” says Clinton.19 Bush Sr. trumpets “an ethic of community service” and rhapsodizes about solving “pressing human problems” by means of “a vast galaxy of people working voluntarily in their own backyards.”20 Bush Jr. tells us that “Where there is suffering, there is duty” and that “Americans are generous and strong and decent, not because we believe in ourselves, but because we hold beliefs beyond ourselves”; thus, he asks us “to seek a common good beyond our comfort” and “to serve our nation” by “building communities of service.”21

Keyes, Buckley, and their ilk advocate mandatory service. Keyes claims that “citizenship in the end is about understanding that each and every individual must offer and must participate in the national life”; thus, he wants to establish a system in which “people are thrown together to live for a couple of years a common life of service.”22 Extending the mandatory-service agenda to the realm of business, Buckley calls for “a national corporate commitment to public service,” acknowledging: “I sound like a goddamned socialist!”23 Which brings us back to Clinton, who, applying the same idea to the realm of education, urges “every state to make service a part of the curriculum in high school or even in middle school,” adding: “There are many creative ways to do this—including giving students credit for service, incorporating service into course work, putting service on a student’s transcript, or even requiring service as a condition of graduation, as Maryland does.” (In 1993, Maryland became the first state in America to require community service as a condition of high school graduation. Since then, hundreds of school districts nationwide have followed suit.) Why? Because, says Clinton: “Every young American should be taught the joy and the duty of serving, and should learn it at the moment when it will have the most enduring impact on the rest of their lives.”24 General Powell chimes in, admonishing young people: “Listen, you’re going to be a real citizen in this country; you have to serve; you have to do something in service to your community.” How? Powell tells them: “By tutoring younger children or working at a hospice or homeless center.”25 And so forth.

But, one might ask, what about individual rights? What about the basic principle of America? How does mandatory service reconcile with the right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness? And what about a child’s education? What about his future? Shouldn’t he be learning math, science, English, and history during school hours—not “volunteering” or being forced to serve the homeless?

Powell’s answer: “If you want to know what violated my rights, it was integral calculus, not community service.”26

So, teaching a child math is a violation of his rights, but forcing him to empty a stranger’s bedpan is not? Surely the General is joking. As to the reason for his sarcasm, we will get to that later.

The point here is that the goal of the “community service” crusade is to spread the idea that in order to be “moral” one must be altruistic—one must selflessly serve others.

Given the self-sacrificial nature of altruism, it is not surprising that some people reject it altogether—in both its religious and its social forms. But the rejection of a negative is not the adoption of a positive. And in the absence of a rational replacement, the only alternative to altruism is the so-called “selfishness” of personal subjectivism.

Personal subjectivism is the view that truth and morality are matters of personal opinion. Its slogans are: “What’s true for you may not be true for me” and “Who’s to say what’s right?” Its basic moral tenet is: Do whatever you feel like doing. In other words: There’s no such thing as morality.

On this view, values are entirely a function of personal feelings. As the British philosopher Bertrand Russell puts it: “When we assert that this or that has ‘value,’ we are giving expression to our own emotions, not to a fact which would still be true if our personal feelings were different.”27

Accordingly, a personal subjectivist values whatever he feels like valuing; he acts however he feels like acting. If he feels like sacrificing other people, he does so. He is not concerned with individual rights; he cares only about his feelings. Since he feels that he creates his own morality, he feels that he is entitled to place his feelings above all else—including the rights of others (which he may or may not feel that they have). This mentality is demonstrated by criminals who, when asked why they committed such-and-such a crime, reply in so many words: “Because I felt like it.”

The most common form of personal subjectivism is hedonism: the theory that being moral consists in acting in whatever manner gives you pleasure. (Hedone is Greek for pleasure; “hedonism” means “pleasure-ism.”) According to hedonism, pleasure is the standard of morality. And while “pleasure” may sound less subjective than “feeling” as the standard, in practice the two are the same. Morally speaking, “Because it gives me pleasure” means “Because I feel like it.” Hedonism is just glorified personal subjectivism.

A textbook example of a personal subjectivist is Eric Harris, one of the murderers of twelve students and a teacher at Columbine High School (Littleton, Colorado, 1999). Prior to the massacre, Harris had expressed his philosophy in no uncertain terms: “My belief is that if I say something, it goes. I am the law, and if you don’t like it, you die. If I don’t like you or I don’t like what you want me to do, you die.”28 He acted on that very belief.

Such ideas are horrifying. If we want to live as civilized beings, we need a code of moral principles to guide us not only in living our own lives, but also in recognizing the rights of others to live theirs. We need a code of values by reference to which we can say with moral certainty that some choices and actions are absolutely right and others are absolutely wrong.

This is one reason why, despite the sacrifices it requires, many people turn to religion: God is widely believed to be the only possible source of an absolute morality. This view is expressed succinctly in a popular book titled The Ten Commandments, by Dr. Laura Schlessinger and Rabbi Stewart Vogel:

To believe in God is to believe that humans are more than accidents of nature. It means that we are endowed with purpose by a higher source, and that our goal is to realize that higher purpose. If each of us creates his own meaning, we also create our own morality. I cannot believe this. For if so, what the Nazis did was not immoral because German society had accepted it. Likewise, the subjective morality of every majority culture throughout the world could validate their heinous behavior. It comes down to a very simple matter: Without God there is no objective meaning to life, nor is there an objective morality. I do not want to live in a world where right and wrong are subjective.29

I don’t want to live in such a world either. And an objective morality is precisely what is needed. But the question remains: Does religion provide it? Is a God-based morality really objective? If not, it is no antidote to subjectivism.

“Objective” means “fact-based.” For morality to be objective, it has to be based on a standard of value derived not from feelings, but from facts. Convinced that no such standard can be found here in the natural world—and justifiably horrified by what is believed to be the only alternative (subjectivism)—many people turn to the supernatural, to God, in hopes of filling the moral void. And God is believed to solve the problem. On the premise that He is the creator of all things and the source of all truth, His moral authority is absolute. Thus, being good is pretty straightforward: Simply obey God’s commands—whatever they are—and the problem is solved.

Until you think about it.

There are hundreds of religions. Each is vying for your allegiance. Each denies the validity of the others. Each claims to be based on the “true” word of God. And each says that God said something different from what the others say He said.

Why? Why can’t any single religion convince the others of its divine “truth”? Because none can provide rational evidence in support of its particular assertions. And given the religious method of arriving at the “truth,” none can justify demanding such evidence from the others either.

Religion is based explicitly, not on reason, which requires evidence and logic, but on faith, which is belief in the absence of evidence and in defiance of logic.30 Faith is essential to religion, because it is the only way to maintain belief in the existence of God: There is no evidence for Him; there are only books and people that say He exists. (This fact can be verified by asking any religionist to present the evidence on which his belief in God rests.)

How, then, do religionists attempt to justify their belief in God? By insisting, as does Dr. Laura, that God is “not an aspect of nature but a reality greater than the universe” and “beyond our sensory abilities.”31

But that raises the question: How can anyone know anything about that which is “not an aspect of nature” or “greater than the universe” or “beyond our sensory abilities”? Nature is all there is; the universe is the totality of it; and our senses are our only source of information. In other words, such “knowledge” would require understanding of a non-thing from a non-place by means of non-sense.

This is why religionists of all walks ultimately echo the famous words of Saint Augustine: I do not know in order to believe; I believe in order to know.32

By dismissing the requirement of evidence—and thus reversing the order of knowledge and belief—faith sets the stage for belief in “miracles.” A miracle is (supposedly) when something becomes what it has no natural potential to become (water turns into wine, or a woman into a pillar of salt)—or when something acts in a manner in which it has no natural potential to act (a bush speaks or burns without being consumed). In other words, a miracle is a violation of the laws of nature.

The basic laws of nature are the laws of identity and causality. The law of identity is the self-evident truth that everything is something specific; everything has properties that make it what it is; everything has a nature: A thing is what it is. (A rose is a rose.) The law of causality is the law of identity applied to action: A thing can act only in accordance with its nature.33 (A rose can bloom; it cannot speak.)

Insofar as our thinking is in accordance with the laws of identity and causality, our thinking is in accordance with reality; insofar as it is not, it is not. Our method for checking our ideas against the facts is logic: the method of non-contradictory identification.34

The basic law of logic is the law of non-contradiction, which is the law of identity in negative form: A thing cannot be both what it is and what it is not at the same time and in the same respect.35 (A rose cannot simultaneously be a non-rose.) The law of non-contradiction is the basic principle of rational thinking. Since a contradiction cannot exist in nature—since things are what they are—if a contradiction exists in our thinking, then our thinking is mistaken and in need of correction. (If we believe that a bush spoke or burned without being consumed, then we need to correct our thinking.)

The laws of identity, causality, and non-contradiction are not rationally debatable. To begin with, all arguments presuppose and depend on their validity; any attempt to deny them actually reaffirms them. This phenomenon was first discovered by Aristotle and is called reaffirmation through denial. While trying to deny these laws, a person has to be who he is—he can’t be someone else—because of the law of identity; he has to act as a human being—he can’t act as an eggplant—because of the law of causality; and he has to use words that mean what they mean—he can’t use words that mean what they don’t—because of the law of non-contradiction. On a more practical level, these laws are why we fuel our cars with gasoline—why we refrigerate certain foods—why we wear warm clothing in winter—why we vaccinate our children—why we string our tennis rackets—why we put wings on airplanes—and why we don’t drink Drano. More broadly speaking, the entire history of observation, knowledge, and science is based on the laws of identity, causality, and non-contradiction. Every object, every event, every discovery, and every utterance is an example of their validity. These laws are self-evident, immutable, and absolute.

Yet religion flatly denies them.

Different religions go to different lengths in this regard, but all of them deny natural law and logic. Such denial is essential to religion, because if a thing cannot become what it has no natural potential to become, or act in a manner contrary to its nature, then there can be no miracles. In other words, if natural law is immutable, then there can be no omnipotent God capable of overriding, suspending, or muting it.

Thus, the more religious a person is, the more he has to try to defend contradictions. Such an effort is by nature frustrating, because contradictions are by nature indefensible. This is why the staunchest defenders of religion say the nuttiest things. For instance, while responding to criticisms of the illogic of religious dogma, the outspoken church father Tertullian finally declared: “It is by all means to be believed, because it is absurd. . . . The fact is certain, because it is impossible.”36

According to religion, God’s existence and mysterious ways are incomprehensible to reason—which means they don’t make sense. God is purported to be greater than nature and unrestrained by natural law—which is what “supernatural” means. Hence, His existence and authority cannot be proved but must be accepted on faith—that is, in the absence of evidence and in defiance of logic. “To those who have faith,” the argument goes, “no explanation is necessary; to those who do not, no explanation is possible.”

This is how an argument for God always ends. One believes because one believes—which means: because one wants to. Religion is a doctrine based not on facts, but on feelings. Thus, claims to the contrary notwithstanding, religion is a form of subjectivism.

In light of this fact, it should come as no surprise that while secular subjectivism denies some of religion’s unproved, evidence-free claims, it demands and employs the very same methods—faith, mysticism, and dogma.

For instance, according to the Nazis, Hitler’s will determined the truth. As expressed by the commander in chief of the Nazi air force, Hermann Goering: “If the Fuhrer wishes it then two times two are five.”37 Goering elaborated the Nazi position as follows in his book titled Germany Reborn.

Just as the Roman Catholic considers the Pope infallible in all matters concerning religion and morals, so do we National Socialists believe with the same inner conviction that for us the Leader is in all political and other matters concerning the national and social interests of the people simply infallible. Wherein lies the secret of this enormous influence which he [Hitler] has on his followers? . . . It is something mystical, inexpressible, almost incomprehensible which this unique man possesses, and he who cannot feel it instinctively will not be able to grasp it at all.38

According to the Nazis, to feel Hitler’s mystical authority and infallibility is to know it—and feeling it is the only way to know it. In other words: “To those who feel it, no explanation is necessary; to those who do not, no explanation is possible.”

Exactly.

The subjectivism feared by religionists is a product of the very method demanded by religion. The Nazis relied on faith as their primary ally in the campaign to convince people of Hitler’s divine authority and the superiority of the “master race.” They could not offer any evidence in support of these things—because none exists. They could not offer logical arguments in support of them—because none are possible. But they could demand belief in the absence of evidence and in defiance of logic—and that is what they did.

Now, of what practical use was faith to the Nazis? What was it that they desperately wanted people to do, but could not rationally persuade them to do? The appeal to faith was the Nazi means of convincing people that they had a moral duty to ignore all personal concerns in favor of serving the group. In Mein Kampf, Hitler wrote that the individual must “renounce putting forward his personal opinion and interests and sacrifice both. . . .”

This state of mind, which subordinates the interests of the ego to the conservation of the community, is really the first premise for every truly human culture. . . . The basic attitude from which such activity arises, we call—to distinguish it from egoism and selfishness—idealism. By this we understand only the individual’s capacity to make sacrifices for the community, for his fellow men.39

Sound familiar?

The Nazis harnessed people’s willingness to “just believe.” Combining religious mysticism and secular subjectivism, they were able to gain adherents without a shred of evidence in support of their claims. Hitler’s alleged God-like will was purported to be the standard of truth. “The community” was put forth as the highest value. “The individual’s capacity to make sacrifices” was trumpeted as the greatest virtue. The subordination of the individual to society was said to be the essence of a “truly human culture.” The people did not challenge this. They did not ask for evidence. They did not use logic. They simply had faith. In Augustinian terms: They first believed in order that they could then know.

Observe the pattern here. Posing as representatives of an alleged God’s all-powerful, all-knowing, all-benevolent will, religious leaders convince people of a moral duty to sacrifice selflessly in service of God’s “higher purpose.” On behalf of Hitler’s allegedly omnipotent and infallible will, and toward a so-called “truly human culture,” Nazi leaders convinced people of a moral duty to sacrifice selflessly in service of their “fellow men” or the “master race” (depending on whether or not they were “Aryan”). In the name of the “proletariat,” and toward an anti-individual “utopia” of collectivism, communist leaders convince people of a moral duty to sacrifice selflessly in service of the “community” (hence the name communism). In the name of “compassion,” and toward the so-called “common good,” America’s advocates of social subjectivism convince people of a moral duty to sacrifice selflessly in service of the “politically correct” group du jour—the “race,” the “class,” the “gender,” the “homeless,” the “community,” the “nation,” or simply “society.” And snarling, “I am the law” and “If I say something, it goes,” personal subjectivists convince themselves of their “right” to sacrifice whomever they want to sacrifice.

Now observe what is being argued. Religion claims that everyone should sacrifice himself and that the beneficiary should be “God.” Social subjectivism claims that everyone should sacrifice himself and that the beneficiary should be “society.” And personal subjectivism claims that others should sacrifice themselves and that the beneficiary should be “me.” Each form of subjectivism calls for human sacrifice; the debate is merely over who should sacrifice for the sake of whom.

Finally, observe the evidence offered in support of their claims: zero.

In light of this fact, shouldn’t we ask: Why should anyone sacrifice or be sacrificed for the sake of anyone? What good is human sacrifice? What, other than suffering and death, does it accomplish? And if there is no good reason for human sacrifice, shouldn’t people stop advocating it? Shouldn’t we abandon and condemn any moral code that requires, encourages, or permits it?

In case there are any doubts, history provides conclusive evidence of the sacrificial nature of all three forms of subjectivism. Let us look first at religion.

Countless people have suffered and died in the name of God. Here is just a smattering of the carnage and pain perpetrated on His “behalf.” The Middle Ages were ten continuous centuries fraught with misery and bloodshed in obedience to God’s “merciful will.” During the Crusades, tens of thousands of men, women, and children were massacred for God’s “higher purpose.” From the thirteenth through the eighteenth century, the Inquisition routinely branded people as “heretics,” and then imprisoned, tortured, hanged, or burned them at the stake for the “love” of God. (Victims include the courageous astronomer Giordano Bruno, who was burned alive for the “heresy” of thinking—and the great scientist Galileo, who was sentenced to life under house arrest for defying the Church by reporting the truth.) The Thirty Years’ War was, well, thirty uninterrupted years of Protestants and Catholics slaughtering each other over how best to worship the Almighty. (This feud resumed in twentieth-century Northern Ireland and has continued for an additional forty years—and counting.) In seventeenth-century Massachusetts, Christians held “witch” trials and hanged or crushed to death those whom they felt were “guilty.” Before moving on to his “next life,” the Ayatollah Khomeini issued an Islamic fatwa (a religious decree) against author Salman Rushdie—who is to be executed for “insulting” Allah in his novel The Satanic Verses. In Afghanistan, throughout the turn of the century, the Islamic Taliban regularly beat, jailed, and murdered people for breaking Allah’s laws. (The punished include: women for holding a job or exposing their ankles, men for failing to wear a beard, homosexuals for existing, and anyone for partaking in activities such as playing music, dancing, playing soccer, playing cards, taking photographs, or flying a kite.) In 1998, Terrorist Osama bin Laden and his Muslim cohorts issued a fatwa declaring: “To kill the Americans and their allies, civilians and military, is an individual duty for every Muslim who can do it in any country in which it is possible to do it.” This, they said, “is in accordance with the words of Almighty God.”40 Such faithful terrorists ceaselessly plot and occasionally strike against “the Great Satan” America by such means as hijacking commercial airliners and crashing them into skyscrapers full of people. In the Middle East, the so-called “Holy Land” over which Islamic terrorists regularly spill Jewish blood has not seen peace since religion began. Religious disputes between Eastern Orthodox Christians, Roman Catholics, and Muslims are at the core of centuries of hatred and the ongoing bloodbath in the Balkans. And in America, anti-abortionists shoot doctors dead for tampering with God’s “divine plan” and bomb abortion clinics because women dare to assume that they, rather than God, own their bodies.

Of course, each religion and sect denounces the others and objects to their ways, calling them “aberrations,” “fringe fanatics,” “cultists,” “extremists,” “defects,” “misinterpreters of God’s will,” or just plain “wrong.” But by what standard? Each claims to get its morality by means of “revelation” from God; thus, each claims to have “divine” authority to act as it does. And since none can prove that its particular creed is right, none has any standard by which to show that the others are wrong. They all just feel it.

I could go on and on about the baseless and sacrificial nature of religion; instead, however, I will defer to Jean Meslier, a guilt-ridden priest who conceded the following in his last will and testament, titled Common Sense:

We have seen, a thousand times, in all parts of our globe, infuriated fanatics slaughtering each other, lighting the funeral piles, committing without scruple, as a matter of duty, the greatest crimes. Why? To maintain or to propagate the impertinent conjectures of enthusiasts, or to sanction the knaveries of imposters on account of a being who exists only in their imagination.41

As Voltaire said: “If we believe in absurdities, we shall commit atrocities.”

Amen.

Amazingly, social subjectivism has an even more horrifying and bloodier history than religion does—and over a much shorter period of time. In the twentieth century alone, over a hundred million people were sacrificed in the name of some group’s “greater good.” Various socialist regimes—communists, Nazis, and fascists—starved, tortured, and slaughtered men, women, and children for the sake of the “community” or “proletariat” or “race” or “peasants” or “farmers” or “nation” or some other collective. In each case, human sacrifice was considered a moral imperative and thus became a political policy. The atrocities perpetrated in the concentration camps of Nazi Germany, the purges and gulags of Soviet Russia, and the killing fields of communist Cambodia are too well known to warrant recital here. Suffice it to say that until the atrocities of Black Tuesday (September 11, 2001), the human sacrifice caused by social subjectivism made the human sacrifice caused by religion look comparatively humane.

Finally, there is personal subjectivism—the creed of common criminals, sundry lowlifes, and creatures of prey that sacrifice people because, well, they want to. This mentality is responsible for countless murders, rapes, muggings, robberies, and frauds. Read any newspaper for details.

It is painfully obvious that all three forms of subjectivism necessarily lead to physical conflict and destruction. What is also true, but not so obvious, is that each one necessarily leads to spiritual conflict and destruction—to conflicting ideas and emotions—to destruction of the mind. Again, let us take religion first.

To the extent a person is religious, he believes that he has a duty to self-sacrificially serve God. This duty requires him to abandon his own selfish dreams. If he sticks to his faithful convictions and abandons his dreams, he cannot be happy, because his dreams go forever unrealized. Conversely, if he hypocritically abandons his convictions and pursues his dreams, he still cannot be happy, for he is filled with moral guilt and dread of divine retribution.

Of course, few people take religion as seriously as did Abraham who, according to the Bible, was willing to murder his son in order to please God. And few are as dedicated as the medieval saints who, in order to avoid the sin of selfish pleasure, drank muddy water, sprinkled ashes on their food, used rocks for pillows, and flogged themselves for having sexual desires.42 But the point is that to whatever degree a person does accept the idea that he should sacrifice his own interests for the sake of God, he will suffer: either from guilt and fear or from psychological repression—or both.

Consider a young woman who longs to become a great ballerina, but cannot reconcile such a purely self-interested goal with her religious conviction that she ought somehow to selflessly serve God. If she chooses to pursue her interest in dance, she cannot be happy, because she will feel guilty and live in fear. If she chooses to become a nun or a missionary, or to serve God in some other way, she still cannot be happy, since her personal dream will go forever unrealized. And if she compromises—if she pursues dance less seriously than is necessary to realize her full potential, and in the place of that surrendered portion of her dream she somehow serves God’s “higher purpose”—then she will get exactly what you would expect: a compromised, semi-guilty, semi-repressed sort of happiness. For she could have either sacrificed more to “glorify” God or worked harder to achieve her dream. She could have been either more “moral” or more selfish.

Fortunately, adherence to religion is losing popularity. Unfortunately, in its stead, people are turning to the other forms of subjectivism.

Consciously or not, many people have accepted the ethics of social subjectivism. They believe that their own welfare and happiness are morally subordinate to the welfare and happiness of some group: a race, a class, a gender, a culture, a nation, or “others” in general. Taken straight, few people could swallow this notion. But it is rarely given straight. To make the sacrifice required by this creed more palatable, the altruistic pill is usually coated in hedonistic sugar and called “utilitarianism.”

In his book titled Utilitarianism, the British philosopher John Stuart Mill writes: “The creed which accepts as the foundation of morals ‘utility’ or ‘the greatest happiness principle’ holds that actions are right in proportion as they tend to promote happiness; wrong as they tend to produce the reverse of happiness.” Importantly, however:

That standard is not the agent’s own greatest happiness, but the greatest amount of happiness altogether; and if it may possibly be doubted whether a noble character is always the happier for its nobleness, there can be no doubt that it makes other people happier, and that the world in general is immensely a gainer by it.43

Now, few people go so far as to ask themselves, “How can I act to make the whole world happy?” But, again, to the degree a person believes that he should selflessly serve others, his own happiness is thereby thwarted—one way or another.

Consider a young man who aspires to be a great classical pianist but cannot reconcile such a thoroughly self-interested career with his altruistic conviction that he is first and foremost a member of an ethnic group, and thus has a moral duty to live for “his people”—not for himself. Classical piano is not considered a part of the cultural heritage of “his people,” and his pursuit of it would not contribute to their “needs.” In fact, it would remove him from the community where most of them live; it would require that he leave them behind. If he chooses to pursue piano, he cannot be happy, because he will suffer from guilt and shame for abandoning his ethnic group. If, instead, he dutifully stays in his community and becomes a teacher, he still cannot be happy, for he will never hear the beautiful music he could have made. And if he compromises—if he pursues piano less seriously than his dream requires, and spends his “spare” time and energy performing some kind of community service—then the effect is predictable: a compromised, semi-guilty, semi-repressed sort of happiness. Like the dancer, he could have either sacrificed more to serve others or worked harder to achieve his dream. He could have been either more “moral” or more selfish.

The point is that if altruism is moral—if morality is a matter of self-sacrificially serving others—then morality is an impediment to your life and happiness: Being good is not good for you. Either life is a paradox in which it is neither practical to be moral nor moral to be practical, or self-interest is moral. It is one or the other.

Take another example. Consider a young girl who dreams of becoming a great physicist. Such a goal requires that she apply herself to her fullest potential in her studies. She must devote her time and effort to achieving the highest level of understanding possible; she has to earn her way into a top university; she needs to learn from the best minds in the field. She cannot compromise: If she does, she will not make it.

But suppose that one day a General, in his military uniform, visits the girl’s school and tells her and her classmates, as he is fond of telling children: “Listen, you’re going to be a real citizen in this country.”

“What do you mean?” asks the wide-eyed, ambitious little girl.

“You have to serve,” says the General, “you have to do something in service to your community.”

“Would you be more specific, sir? What do you mean? Exactly how must I serve?” asks the active-minded, curious child.

“By tutoring younger children or working at a hospice or homeless center,” says the General.

“But why?” asks the persistent and brave young girl. “Why should I serve others at the expense of my own dream? What about my studies? What about the fact that I want to be a great physicist, not a social worker? If I am to succeed, I need to become an expert at math and science, not at ladling soup. And what about the basic principle of America? Don’t I have a right to my own life and the pursuit of my own happiness?”

“If you want to know what violated my rights,” quips the General, “it was integral calculus, not community service.”

Observe that the little girl has asked the General for a reason, but he has not given her one. She has asked him why she must serve others at the expense of her own dream, but he has not told her why. She has asked him to reconcile his position with the basic principle of America, but he has not done so. Instead, he has evaded her questions by resorting to sarcasm. Why? Why won’t he give her a straight answer? Because he can’t. There is no rational justification for what he says she must do; there is no rational justification for self-sacrifice.

There simply are no facts to support the claim that the little girl should spend some of her precious time and energy manning a ladle in a soup kitchen, or sponge bathing the elderly, or in some other way emulating Mother Teresa. The General can say that the little girl has to serve her community, but he cannot say why she has to do so. Hence his sarcasm: It is an attempt to avoid having to give a reason for his claim—a claim for which no reason can be given.

If the sarcasm doesn’t work, if the little girl continues to demand a reason why she should self-sacrificially serve others, the General might try appealing to an alleged authority—whether himself (“Because I said so”) or some “higher” authority such as “God” or “society.” And if that doesn’t work, if the little girl rejects those fallacious appeals, the General might try appealing to force; he might try making the child serve others against her will (as his altruistic allies in Maryland do). But whatever he does, he cannot appeal to reason, because there is no reason why the little girl should serve others at the expense of her own dream.

What if the General succeeds? What if his sarcasm works? What if he artfully dodges the little girl’s questions and badgers her into accepting the creed of self-sacrifice? To the extent she accepts it, like the dancer and the pianist, her life will be thwarted by moral guilt, compromise, and repression. What if the General appeals to authority and that works? What if he convinces the little girl that he or God or society just knows that she must sacrifice herself for others—but that no reason can be given, and that in order to understand, she must simply feel it or accept it on faith? Again, to the degree she accepts it, her life will be retarded by moral guilt, compromise, and repression. And what if the General appeals to force? What if (Maryland-style) he makes the little girl serve others against her will? To the extent he imposes such force on the child, her life will be impeded by, well, involuntary servitude—which, in principle, is slavery.

Whatever the means, if the General has his way, damage will be done. Every moment of life counts. Every amount of effort matters. Once time and energy are spent, they cannot be retrieved. Thus, if the little girl is convinced to sacrifice or forced to serve, she will not be able to make up her loss. That much of her dream will be out of her reach forever.

Now, what are we to make of an adult’s efforts to coerce or convince a little girl to serve others at the expense of her own long-range goal in life? Bear in mind: We are not talking here about an adult trying to guide a child to act in her own long-term best interest—that is precisely what the little girl in question is trying to do. Rather, we are talking about an adult’s attempt to thwart that process by persuading the child to put her time and effort elsewhere, by evading her questions as to why, by appealing to authority, or by using physical force.

I submit that for an adult to sacrifice himself is immoral—but for an adult to force or encourage the sacrifice of a child is evil.

People live once. Ideas have consequences. Human sacrifices are being encouraged and performed as you read. Altruism, in both its religious and its secular forms, is crippling the lives of real men, women, and children every day. You probably know some of them. You may be one of them. I was.

There is only one way to combat a morality that is against human life, and that is by embracing a morality that is for human life—a non-sacrificial morality—the morality of self-interest.

But, one might ask, doesn’t self-interest imply personal subjectivism? Don’t selfish people do whatever they feel like doing? Don’t they harm others for their own benefit? And how can an advocate of selfishness say that sacrificing other people is wrong?

To begin answering these questions, let us observe the so-called “selfishness” of a personal subjectivist. He, too, has dreams—and he feels that he can “achieve” them in whatever fashion he wants to. If he feels like sacrificing other people—so be it! According to his philosophy, he is the law; thus, he makes up the rules as he goes.

Consider a hedonist who wants the pleasures that money can bring but doesn’t feel like being productive. Working, he says, is just not his thing. So he decides to steal pocketbooks—they can be full of cash and are relatively easy to snatch. Sure enough, with a few select purses a day, the money starts to flow, and he feels that he is on his way to achieving his dream. In just a few months, he has stolen thousands of dollars and has moved into a fashionably furnished big-city apartment.

But for some reason, he still feels empty. His friends lie and try to steal from him; surprisingly, they, too, are crooks. He can’t seem to keep the attention of any quality women; they all want to talk about career goals, achievements, and ambitions. The party scene has gotten old; there is really nothing to celebrate. Of course, the money is still “good,” and the routine has become even easier with repetition. But somehow life just seems meaningless.

So he decides to rob a bank. He figures that if he can pull-off one big “job” and make it to the islands with a million dollars in his suitcase, he will never have another discouraging day. He begins to plan the heist. “Selfish” bliss is just over the horizon. . .

Or is it?

What if he makes it? Some criminals have. What will he do on the island? Go scuba diving? Watch TV? Get drunk? “Hang out” with other criminals? Pretend that he is a man of virtue in order to associate with good people to whom he has lied? Who will be his lover? Will she be intelligent, passionate, and have good character? Or will she be ignorant, boring, and likely to steal his stolen money? How will he sleep at night? How will he feel when he wakes up in the morning? How will he face each day? Will he be fearless and eager to meet his next challenge? Or will he be timid and terrified that the law might catch up with him? What will be his true inner state? Will it be one of harmony—or one of anxiety?

The point is: It doesn’t matter if he makes it. He can’t possibly achieve happiness by his chosen method. If asked, he might swear up and down that his is a life of pure pleasure. But so what? Words cannot reverse cause and effect. Words cannot change the fact that genuine happiness can be achieved only by means of honest effort. And while even a bank robber probably knows this on some level, even if he doesn’t, his ignorance is not bliss. His is a life of emptiness, self-contempt, loneliness, and decay. Emptiness, because he has no rational ambitions or productive goals. Self-contempt, because he knows that he is a parasite. Loneliness, because he is incapable and undeserving of friendship or love. And decay, because he does not use his mind, and there is no such thing as a dormant mind: One that does not grow, rots. Such a person is rotting spiritually from the inside out.

Of course, few people are as brazenly irrational as is our hedonist bank robber. But irrationality of any kind or degree is incompatible with genuine happiness: The psychological results vary in proportion to the extent of one’s subjectivism. To the extent a person allows irrational desires to dictate his choices and actions, he will be unhappy. To the degree he does whatever he feels like doing without regard to both the short-range and the long-range consequences—including both the physical and the spiritual effects—he will suffer.

For example, a businessman who “just occasionally” swindles his way through a deal thereby ruins his potential for genuine happiness. He might have wads of money, a big summerhouse, a trophy wife, a yacht, and lots of so-called friends, but he still cannot be happy. Not if happiness requires harmony with reality: By pretending that facts are other than they are, he has set himself in conflict with reality. And not if happiness requires self-respect: He has been dishonest—and he knows it. In addition to the fact that he is a fraud and might get exposed to the world as such, even if he doesn’t get physically “caught,” the swindler still has major self-imposed problems. Either he lies to his so-called friends about the nature of his success, in which case they are not friends—or he doesn’t, in which case they are swine, too. His wife would hate him if she knew him—or worse, she would not. And though he may be too blind to see it, or too belligerent to admit it, he is not happy. Neither ignorance, nor insistence, nor more fraud can change that fact.

Regardless of what they might say, personal subjectivists are miserable people, and they are so by their own design. Yet they are typically considered “selfish.” Is that an appropriate label for them? Does it make any sense to call a person “selfish” for extinguishing the very possibility of his own happiness? Not if selfishness means concern for one’s own well-being. Spiritual self-destruction is no more in a person’s best interest than is physical self-destruction; we would not call a person selfish for mutilating his own hand, and we should not call him selfish for mangling his own mind.

Neither bloody murderers, nor big-time bank robbers, nor small-time purse-snatchers, nor occasional swindlers are selfish—not in the true meaning of the term. And it is no coincidence that none of them are happy. Blindly following one’s feelings—evading, ignoring, or denying the requirements of one’s actual, long-term well-being—is not in one’s best interest. Irrationality is not selfish; it is selfless.

For a policy to be selfish, it has to account for one’s actual nature and needs—both material and spiritual; and it has to account not only for the present, but also for the more distant future. A policy of self-interest must recognize the fact that man is a being of body and mind whose life occurs not for just a moment or a day, but for a span of years and decades.

If being selfish were a matter of acting on one’s feelings, it would not be conducive to happiness. But it isn’t a matter of acting on one’s feelings. As we will see, being selfish consists in thinking logically and acting on long-range principles toward life-serving goals—both material and spiritual. Being selfish consists in being rational.

Of course, few people attempt to go only by their feelings or to be consistently selfless—and the few who do don’t live for long. Merely to keep breathing, a person must use logic and be selfish to some degree. Thus, people who accept the idea that being moral consists in being selfless have to cheat on their moral convictions just to stay alive. While they sacrifice their own interests to some degree, as they believe morally, in order to be good, they should—they also pursue their own interests to some degree, as they know selfishly, in order to live, they must.

Aware that this means they are not being fully moral, such people rationalize their selfish pursuits with slogans such as “Nobody’s perfect” and “Morality is not black and white.” Simultaneously, they sabotage their personal interests with slogans such as “You have to compromise” and “Don’t set your sights so high.” This means they have accepted the notion that moral consistency is incompatible with personal happiness. Thus, they betray both—by instituting a personal policy of moral compromise. In so doing, they cut themselves off from life as it ought to be and settle for a semi-guilty, semi-repressed, watered-down sort of happiness.

If “morally” you should be selfless, but “practically” you must be selfish, then life is an obscene paradox: The moral and the practical are hopelessly at odds; being good is not good for you.

A solution to this dilemma requires the discovery of a morality that neither requires nor permits the sacrifice of anyone to anyone. What is needed is a non-sacrificial morality—a code of values that accounts for the actual, long-term, material and spiritual requirements of human life. But such a code, to be defended, must be based on a foundation other than faith or feelings, and such a foundation is thought to be impossible.

So the debate between religion and secular subjectivism continues, with both sides accepting the premise that an absolute morality requires the existence of God. The religionists fearfully assert: “God must exist. And since you can’t prove that He doesn’t, I say that He does and that His moral law is absolute. Being moral consists in glorifying God, obeying His commandments, and sacrificing in service of His higher purpose.” To which the secular subjectivists skeptically reply: “You can’t prove the existence of God, so I don’t accept it. I say his so-called moral law is your Sunday-school fantasy. Morality is not absolute; it is a matter of personal preference or social convention. If I (or my group) say something, that’s the moral law. And, yes, there will be sacrifices, but they will not be for your imaginary God; they will be for me (or my collective).”

Hence the alleged alternative: Either sacrifice yourself or sacrifice others. In other words, your choice is: masochism or sadism.

That is not a good alternative.

If we want to live happily—if we want to pursue our values guiltlessly, with integrity—we need a third alternative; we need to discover a non-sacrificial code of morality. And to defend such a code, we need to ground it logically in observable facts; we need to discover a natural, provable, objective standard of value on which to base it. Without such a code built on such a foundation, the sacrificial moralities of subjectivism are unanswerable. And on the terms of such moralities, a life of genuine happiness is unattainable.

Yes, there is a non-sacrificial code of morality—and an objective standard of value on which it is based. But on the road to their discovery, there appears to be an obstacle.

Author’s note: Chapter 2 of Loving Life is titled, “The Is–Ought Gap: Subjectivism’s Technical Retreat.” The book is available from Barnes & Noble, Amazon.com, and the Ayn Rand Bookstore.

You might also like

Endnotes

1 John R.W. Stott, Basic Christianity (London: InterVarsity Press, 1971), p. 78.

2 Abraham Heschel, God in Search of Man, A Philosophy of Judaism (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1983), p. 117.

3 Walter C. Kaiser Jr. et al., Hard Sayings of the Bible (Illinois: InterVarsity Press, 1996), p. 127.

4 Stott, Basic Christianity, p. 79.

5 See Genesis, 2–3.

6 Saint Augustine, City of God, trans. Gerald G. Walsh et al. (New York: Doubleday, 1958), p. 314.

7 Genesis, 22:2.

8 Augustine, City of God, p. 313, emphasis added.

9 The Philosophical Works of Descartes, trans. Elizabeth S. Haldane and G.R.T. Ross (London: Cambridge University Press, 1973), Vol. I, p. 253.

10 Robert C. Mortimer, Christian Ethics (London: Hutchinson’s University Library, 1950), p. 8.

11 Kaiser, Hard Sayings of the Bible, p. 126.

12 Mortimer, Christian Ethics, pp. 7–8.

13 See Ancilla to the Pre-Socratic Philosophers, trans. Kathleen Freeman (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1996), p. 125; and Wilhelm Windelband, A History of Philosophy (New York: Harper & Row, 1958), Vol. I, pp. 91–94.

14 See Immanuel Kant, Critique of Pure Reason, trans. Norman Kemp Smith (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1929), esp. pp. 22–25; Prolegomena, trans. Paul Carus (Chicago: Open Court, 1997), esp. pp. 79–84; and Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals, trans. Mary Gregor (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1997), esp. pp. 40–41, 58–59.

15 Michael Schudson, Discovering the News (New York: Basic Books, 1978), p. 6.

16 Richard Rorty, “The Next Left,” interview by Scott Stossel, Atlantic Unbound, April 23, 1998.

17 Cf. Richard Rorty, Objectivity, Relativism, and Truth (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1991), esp. pp. 13–14, 21–22, 29; and Achieving our Country: Leftist Thought in Twentieth-Century America (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1998), pp. 27–29, 34–35.

18 Louis P. Pojman, Ethics: Discovering Right and Wrong, 3rd ed. (Belmont: Wadsworth, 1999), p. 78.

19 President Bill Clinton, radio address to the nation, April 5, 1997.

20 President George Bush, quoted in Howard Radest, Community Service: Encounter with Strangers (Westport: Praeger, 1993), p. 8.

21 President George W. Bush, inaugural address, January 20, 2001.

22 Alan Keyes, Washington Journal, C-SPAN, January 19, 2000.

23 William F. Buckley, quoted in Mother Jones, January/February, 1996.

24 President Bill Clinton, radio addresses to the nation, April 5 and July 26, 1997, emphasis added.

25 General Colin Powell, “Helping Hands,” interview by Elizabeth Farnsworth, Jim Lehrer News Hour, April 28, 1997.

26 Ibid.

27 Bertrand Russell, “Science and Ethics,” in Religion and Science (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997), pp. 230–31.

28 Eric Harris, from his website, quoted in The Washington Post, April 29, 1999.

29 Dr. Laura Schlessinger and Rabbi Stewart Vogel, The Ten Commandments (New York: Harper Collins, 1998), p. xxix.

30 Cf. Hebrews, 11:1; and Heschel, God in Search of Man, pp. 117–18.

31 Schlessinger, The Ten Commandments, pp. 25–26.

32 Cf. Saint Augustine, “Tractate 27 on the Gospel of John,” Chapter 6: 60–72. Cf. also Saint Anselm, Proslogium, Chapter 1; and Heschel, God in Search of Man, pp. 121–22.

33 See Ayn Rand, For the New Intellectual (New York: Signet, 1963), p. 151; and H.W.B. Joseph, Introduction to Logic, 2nd ed. (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1916), p. 408.

34 Rand, For the New Intellectual, p. 126.

35 Cf. Aristotle, “Metaphysics,” in The Basic Works of Aristotle, ed. Richard McKeon (New York: Random House, 1941), pp. 736–37.

36 The Ante-Nicene Fathers, eds. A. Roberts and J. Donaldson (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1903), Vol. III, The Writings of Tertullian, p. 525.

37 Quoted in Eugene Davidson, The Trial of the Germans (New York: Macmillan, 1966), pp. 237–38.

38 Hermann Goering, Germany Reborn (London: E. Mathews and Marrot, 1934), pp. 79–80.

39 Adolf Hitler, Mein Kampf, trans. Ralph Manheim (Houghton Mifflin: New York, 1971), pp. 297–98.

40 Osama bin Laden et al., “Fatwa Urging Jihad Against Americans,” in Al-Quds al-‘Arabi, February 23, 1998.

41 Jean Meslier, Superstition in All Ages, trans. Anna Knoop (New York: Peter Eckler, 1889) pp. 37–38.

42 See W.E.H. Lecky, History of European Morals (New York: George Braziller, 1955), Vol. II, pp. 107–12; and St. Bonaventura, Life of St. Francis, trans. E.G. Slater (London: J.M. Dent and Sons, 1910), pp. 329–31.

43 John Stuart Mill, Utilitarianism (Indianapolis: Hackett, 1979), pp. 7, 11, emphasis added. Cf. Immanuel Kant, The Metaphysics of Morals, trans. Mary Gregor (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1996), esp. pp. 151–52, 156, 161, 227.

![[TEST] The Objective Standard](https://test.theobjectivestandard.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/logo.png)