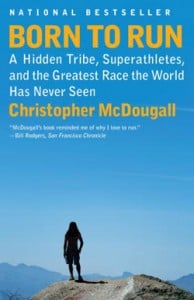

Born to Run: A Hidden Tribe, Superathletes, and the Greatest Race the World Has Never Seen, by Christopher McDougall. New York: Knopf, 2009. 304 pp. $24.95 (deckle edge).

Christopher McDougall’s Born to Run: A Hidden Tribe, Superathletes, and the Greatest Race the World Has Never Seen inspires by showing superathletes running hundreds of miles nonstop across treacherous terrain—and argues that these seemingly superhuman feats can be achieved and enjoyed by practically anyone who excises self-imposed limitations.

Readers first see these superathletes in action in the 1994 running of a brutal “ultra-race” called the Leadville Trail 100. McDougall describes participation in the Leadville 100, high in the mountains of Colorado, as “running the Boston Marathon two times in a row with a sock stuffed in your mouth”—then hiking “to the top of Pike’s Peak”—and then doing it all over again, “this time with your eyes closed.”

That’s pretty much what the Leadville Trail 100 boils down to: nearly four full marathons, half of them in the dark, with twin twenty-six-hundred-foot climbs in the middle. Leadville’s starting line is twice as high as the altitude where planes pressurize their cabins, and from there you only go up (p. 60).

In the 1994 running, a small group of runners from a secretive tribe based in Mexico’s Copper Canyon participated. Called the Tarahumara, they ranged in age from 25 to 42 and ran in sandals, laughing as they left checkpoints more than halfway through the race. They completely dominated the Leadville, finishing first, third, fourth, fifth, seventh, tenth, and eleventh.

The question of how these “stone-age guys in sandals” were able to do it, moreover looking like they were just having fun, has captivated the ultra-running world and McDougall. The explanation McDougall posits was discovered—or, according to the book, rediscovered—by modern doctors, track coaches, anthropologists, and ultra-runners. According to McDougall and the maverick scientists he quotes, we are all born to run, and very long distances at that. McDougall argues that the seemingly superhuman feats displayed by the Tarahumara are achievable by us all if we get rid of barriers that prevent us from doing so, including the modern “junk food” diet and mental limitations with regard to age and sex.

One such barrier, says McDougall, is the modern running shoe. McDougall begins his discussion of running shoes with a blueprint of the human foot, what he calls “a marvel that engineers have been trying to match for centuries.”

Your foot’s centerpiece is the arch, the greatest weight-bearing device ever created. The beauty of any arch is the way it gets stronger under stress; the harder you push down, the tighter its parts mesh. . . . Buttressing the foot’s arch from all sides is a high-tensile web of twenty-six bones, thirty-three joints, twelve rubbery tendons, and eighteen muscles, all stretching and flexing like an earthquake-resistant suspension bridge (p. 176).

This type of foot, McDougall argues, was made to run—but not in the heavily cushioned running shoes that dominate the market. “No stonemason worth his trowel would ever stick a support under an arch; push up from underneath and you’ll weaken the whole structure” (p. 176). On the basis of this reasoning, McDougall states that running shoes “may be the most destructive force ever to hit the human foot” (p. 168).

Backing up this somewhat controversial claim, McDougall cites, among others, a doctor who says “there are no evidence-based studies—not one—that demonstrate that running shoes make you less prone to injury” (p. 171); a professor of biological anthropology who says “a lot of foot and knee injuries that are currently plaguing us are actually caused by people running with shoes that . . . make [their] feet weak” (p. 168); and an Olympic coach who makes the point that if “you support an area, it gets weaker” and if “you use it extensively it gets stronger. . . . Run barefoot and you don’t have all those problems” (p. 182).

To test this idea, 230-pound McDougall, who at the outset of the book ran with seemingly unsolvable pain in his feet, began to train Tarahumara-style—which included ditching his old running shoes. McDougall noticed an almost immediate improvement in his running form. His “back straightened and his legs stayed squarely under his hips” (p. 157). “Instead of each foot clomping down as it would in a shoe, it behaved like an animal with a mind of its own—stretching, grasping, seeking the ground with splayed toes, gliding in for a landing like a lake-bound swan” (p. 183). Further, the foot pain that had plagued McDougall vanished.

With this barrier removed, McDougall shows himself easily surpassing another: the limiting view that running is a “grind” one must struggle through. He learns to enjoy running just like Jenn Shelton, one of the ultra-runners featured prominently in Born to Run. Jenn’s time of 14:57 remains “the fastest hundred miles on dirt trails ever recorded by any women” and when she runs, according to McDougall, you “can tell she’s having an absolute blast, as if there’s nothing on earth she’d rather be doing” (pp. 147–48). McDougall joins Jenn and a new group of ultra-runners in discovering what he says the Tarahumara never forgot: Running can be a sensuous and eminently enjoyable experience.

Like the Tarahumara, these new ultra-runners have also rid themselves of mental barriers with regard to their sex or age. They are keenly aware of the ordinary human potential to do extraordinary things—whether that means a thirteen-year-old girl, such as Mackenzie Riford, “happily running” a 50-miler, or a ninety-six-year-old man, such as Jack Kirk, running a hellacious race that “begins with a 671-step cliff-side climb” (p. 201–2).

McDougall shows these ultra-runners taking “to the woods, [and bringing with them] everything that [has] been learned about sports science” since the 1994 Leadville. Incredible results follow: In 2005, one such runner set a new record at Leadville, finishing “in a stunning 15:42, nearly two hours faster than the fastest Tarahumara ever had” (p. 112). Records like these ultimately lead to the book’s climax: an “underground showdown pitting some of the best ultra-distance runners of our time against the best ultra-runners of all time, in a fifty-mile race on hidden trails only Tarahumara feet had ever touched” (p. 7).

This showdown comes about due to a runner known as Caballo Blanco, who ran alongside the Tarahumara at Leadville, made friends with the group, and then followed them back to their home in Mexico. Caballo wondered what would happen if the best Tarahumara runners went to the event in Leadville, as opposed to merely those few who could be talked into leaving their village. And more:

What could the Tarahumara do if pushed? . . . [Two of the Tarahumara who competed in the Leadville 100] had run like hunters, the way they’d been taught: just fast enough to capture their quarry and no faster. Who knew how much faster they might have gone against [better competitors]? And no one knew what they could do on their home terrain (pp. 112–13).

Caballo intended to answer these questions by organizing the Copper Canyon Ultra Marathon, laying “out a diabolical course; [in which runners will] be climbing and descending sixty-five hundred feet in fifty miles, exactly the altitude gain of the first half of the Leadville Trail 100” (p. 258). Given the near-mythical reputation of the Tarahumara in ultra-running circles, the marathon attracted top competitors—none of whom planned to lose. Jenn Shelton’s plan, in particular, was to “go for broke,” reasoning that “if she lost the race of a lifetime because she’d played it safe, she’d always regret it” (p. 261). Interestingly, McDougall himself competes in the climactic race, something that surprises Caballo, who, seeing him run in the past, had given him the nickname Oso (bear) to humorously point out McDougall’s size and his then-plodding style of running (p. 165). In addition to increasing the drama, McDougall’s participation shows that when he claims all humans are born to run long distances, he means it.

McDougall expertly builds up tension and anticipation for the race, and when the ultra-runners leave the start line hooting and hollering good-naturedly, the reader feels like celebrating in kind. Likewise for the conclusion: The sheer benevolence on display by the participants, regardless of their final placements, tops off this inspiring tale of people joyously pushing their bodies to the limit.

Inspiring though it is, Born to Run has significant flaws, ranging from mundane to comical to tragic. McDougall occasionally argues for his theme, that we are all born to run, by means of unproven speculations about prehistoric man, stating, for instance, that he survived by running animals to death (p. 229). He also undeservedly praises the Tarahumara, who, although undeniably great athletes, have not, as he claims, “solved nearly every problem known to man”; and who should not be praised, as McDougall praises them, for “creating a one-of-a-kind financial system based on booze and random acts of kindness” (p. 14). The Tarahumara exist in a state of abject poverty and relative anarchy. With no government to protect rights and uphold the rule of law, they are at the mercy of criminals—who, as McDougall himself reports, took the life of one of their “talented young runners” (p. 7).

These unfortunate distractions aside, Born to Run is a captivating book about ordinary people performing extraordinary feats and loving the process. By portraying men and women passionately devoted to developing their full potential, the book inspires the reader to develop his.

![[TEST] The Objective Standard](https://test.theobjectivestandard.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/logo.png)