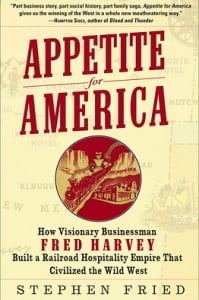

Appetite for America: How Visionary Businessman Fred Harvey Built a Railroad Hospitality Empire That Civilized the Wild West, by Stephen Fried. New York: Bantam Books, 2010. 515 pp. $27 (hardcover).

Granted, the subtitle of Appetite For America: How Visionary Businessman Fred Harvey Built a Railroad Hospitality Empire That Civilized the Wild West is hyperbolic, but author Stephen Fried’s narrative makes a strong case for Fred Harvey’s immense contributions to America’s westward expansion. Fried tells how Harvey and the two generations of Harveys that succeeded him pioneered and developed many business and marketing concepts still in use today.

Fried first covers Harvey’s early years, from his 1853 arrival in New York—as a seventeen-year-old Englishman with only two pounds in his pocket—to his initial venture into food service, which ended when his partner, a Confederate sympathizer, absconded with all their money and left him to start over at twenty-six. Fried next shows Harvey working on packet boats and as a railroad agent, earning the respect of those with whom he worked and formulating the plans for his next venture in food service.

As Fried tells us, Harvey, during his constant railroad travel as an agent, noticed that the food and service at train depots was awful (and often unscrupulous), and he knew he could do better. Thus began Harvey’s initial steps toward the construction of his hospitality empire. Because of Harvey’s excellent relationships with the railroad executives with whom he had worked and his knowledge of the food service business, he and a partner were able to operate three eating houses along the Kansas Pacific Railway. Although these establishments were successful, Harvey soon decided to go out on his own and start the company that would bear his name.

Fried shows that the drive to innovate was part of Harvey’s nature, recounting how he insisted that his Fred Harvey eating houses use the freshest ingredients—which he had shipped by refrigerated rail car. Further, Harvey recognized the importance of retaining the talented chefs he hired, and thus gave them discretion with recipes and even encouraged them to make deals with provisioners in their respective areas to acquire interesting game and produce. Fried shows that the improvements Harvey made to the railway eating house experience were immensely successful, and he covers the amazing expansion of Harvey’s company, which, by the time he died in 1901, was serving travelers in all the eating houses along the Santa Fe line, from the Midwest to California.

Interestingly, as Fried recounts, the old maxim “shirtsleeves to shirtsleeves in three generations” did not apply to the Harvey family. Indeed, the business successfully passed through four generations of Harveys. After Fred Harvey’s death, his son Ford managed the company and drove it to new heights. Fried notes that Ford, like his father, was intelligent, innovative, hardworking—and, especially, cognizant of the immense value of his employees.

To keep in touch with his nearly 7000 employees, and remind them—and himself—of the importance of their work, their loyalty, their integrity, and their ingenuity, Ford would sometimes dictate long conversational memos to be copied and circulated throughout the system. He also sent around copies of speeches he gave to trade groups about the company’s successes and challenges, as well as typewritten versions of any newspaper articles mentioning Fred Harvey service. (pp. 200–201)

Both Fred and Ford Harvey’s superlative management ideas and methods established a company that was built to last. Even when Ford died in the flu epidemic of 1928, the enterprise persevered. Fried covers the transfer of leadership, from Ford to a brain trust of senior executives called the 10th Legion, to Ford’s son Freddy, and then, following Freddy’s untimely death in a plane crash, to Ford’s brother Byron.

Appetite for America surveys the company’s entire amazing ninety-year run, from 1876 to 1966. The story, expertly told by Fried, is in and of itself fascinating and entertaining and reason enough to purchase the book. But along the way Fried offers much more than just the details of the company. For instance, Fried discusses the history and significance of the Harvey Girls, a program that gave young single women a hitherto rare opportunity to be independent and find decent paying jobs. Fried also points out that the Harveys were the first to use branding, most notably in their policy of taking advantage of the reputation of the company’s founder and always referring to anything and everything associated with the company—including “The Fred Harvey Company”—as simply “Fred Harvey.” The Harveys, Fried notes, can even lay claim to creating the first chains of restaurants, hotels, sandwich stands, newsstands, and bookstores. As Fried summarizes in his introduction, Harvey “was Ray Kroc before McDonald’s, J. Willard Marriott before Marriott Hotels, Howard Schultz before Starbucks” (p. xviii). To this day Harvey is considered the founding father of the American food service industry, which, Fried notes, is “why his story and his methods are still studied in graduate schools of hotel, restaurant and personnel management, advertising and marketing” (p. xvii).

Fried shows that the Fred Harvey Company had a significant cultural impact as well.

The restaurants and hotels run by this transplanted Londoner and his son did more than just revolutionize American dining and service. They became a driving force in helping the United States shed its envy of European society and begin to appreciate and even romanticize its own culture. (p. xix)

In addition to helping Americans lose their European envy and providing the Wild West with the civilizing power of superb hospitality, Harvey and his family were instrumental in developing the Grand Canyon as a tourist attraction. The Fred Harvey Company also brought Native American arts and culture to the notice of Americans, and its in-house designer, Mary Colter, famously created the “Santa Fe” style in architecture and design.

Another fascinating aspect of Fried’s book, albeit one he may not have intended, is how the political changes occurring during this period are integrated into the narrative. The reader starts in the 1850s, in the largely laissez-faire world into which Fred Harvey entered, and sees how a businessman of great ingenuity and integrity rose to the top by means of his intelligence and work ethic. Then the reader sees the rise of government interference in the marketplace and the negative consequences this produced. As Fried notes, the Supreme Court in 1886 declared that the federal government had control over interstate commerce. The following year, The Act to Regulate Commerce passed, and with it the railroads, which had previously set prices based on supply and demand, were forced to charge the same rate for the same trip. In 1903, Teddy Roosevelt signed the Elkins Act, which made it illegal for railroads to discount from published rates. This in turn was followed by The Hepburn Act, which “gave the Interstate Commerce Commission unprecedented power to regulate and infiltrate almost every aspect of the industry” (p. 216).

Through Fried’s recounting of these events, readers will come to expect President Wilson’s nationalization of all railroads during World War I. And those who thought that American “czars” were the creation of President Obama will be interested to read about William McAdoo, Wilson’s son-in-law and treasury secretary, who was given the title of director-general of the new U.S. Railroad Administration.

Director-General McAdoo finally had to admit that [Santa Fe Railway President] Ed Ripley had been right during all those years: Government regulation was a big reason why the railroads hadn’t been able to keep investing in new cars and better tracks. The Interstate Commerce Commission had forced them to keep passenger fares and freight rates absurdly low, and even with the recently mandated eight-hour workday, wages had not risen enough to keep those workers who hadn’t enlisted from repeatedly threatening to strike. (pp. 251–252)

McAdoo’s solution? Fire all the presidents of the railroads and replace them for the duration of the war with “federal managers.” The changes these managers implemented forever changed the way railroads would operate. Here is how Fried characterizes it:

Most Americans today are more familiar with the changes and compromises made during World War II, because it lasted longer and is fresher in memory, than with the actions the government took during the first World War. But in many ways, what happened in 1917 and 1918 is far more significant and shocking. This was the first time major industries were impounded in the world’s largest democracy. And quite a few individual freedoms were seriously curtailed as well. (p. 253)

In addition to covering these political developments along the way, Fried peppers the book with fascinating tales related to the railroads’ westward expansion. (Once Harvey established his reputation, the Santa Fe Railway wanted his eating houses wherever it expanded its service.) Although these often appear to be digressions, they serve wonderfully to paint a picture of what America was like when Harvey built and expanded his hospitality empire. One particularly dramatic event Fried details is the story of how the Santa Fe obtained the right to use the most important and strategic mountain pass in the West—Raton Pass—through which only one set of railroad tracks would fit. As Fried reports, the Santa Fe and its main competitor, the Denver & Rio Grande (D&RG), each sent teams of men to El Moro, Colorado, on the same day to negotiate rights to Raton Pass with its owner, Richens “Uncle Dick” Wootton.

The Santa Fe engineers kept a low profile during the ride, and when the train pulled in to the station well after dark, they lagged behind their competitors until they saw them check into the depot hotel for the night. Then they bolted into action, hiring a carriage and horses to head off into the pitch-black to ride 20 bumpy miles to Uncle Dick’s hotel. When they got there, a teen dance was in full swing, and Uncle Dick was about to call it a night. But they were able to keep him awake long enough to talk him into a handshake deal allowing the Santa Fe to build along his pass.

They agreed to work out details later because the process of grading . . . had to begin immediately in order to solidify their legal claim to the pass. Quickly, they hired a ragtag group of teenage boys from the dance, and in the dead of night this motley crew hiked up the mountain carrying lanterns, shovels, and picks to mark off the route that the train tracks would take. (p. 57)

In addition to setting context for the Harvey story, Fried’s retellings of such events add enjoyable hues to an already colorful tale.

In Appetite for America, Stephen Fried skillfully tells a truly American story of rags to riches in a period during which our country was at her freest, when men could make vast fortunes via intelligence and hard work, practically unhindered by laws beyond those that govern the free market. It is a feast for the soul.

![[TEST] The Objective Standard](https://test.theobjectivestandard.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/logo.png)