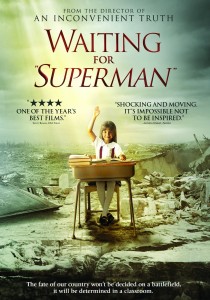

Waiting for “Superman”, directed by Davis Guggenheim

Written by Davis Guggenheim & Billy Kimball

Released by Paramount Vantage (2010). 1 hour, 42 minutes. MPAA Rating: PG.

“One of the saddest days of my life was when my mother told me ‘Superman’ did not exist. ‘Cause even in the depths of the ghetto you just thought he was coming. . . . She thought I was crying because it’s like Santa Claus is not real. I was crying because no one was coming with enough power to save us.” —Geoffrey Canada, Waiting for “Superman”

The documentary Waiting for “Superman” examines America’s failing public education system and calls on Americans to do something about it. Writer/director Davis Guggenheim takes viewers through the entrails of our public schools, showing the horrifying experiences of students across the country (mostly fifth and eighth graders), exposing the policies that led to those experiences, and providing statistics that measure the extent to which our public school system has failed. As part of the exposé, the movie includes several compelling interviews with educators, addressing issues such as the failure of the No Child Left Behind program, the purpose and effects of teachers’ unions, the incredibly high dropout rates among public school students, and the impact of failing schools on our economy and society.

Politically, Guggenheim is clearly left-leaning: He also directed the environmental propagandist documentary An Inconvenient Truth featuring Al Gore. But Guggenheim admits in the opening minutes of Waiting for “Superman” that, when “faced with the reality” of public school education, he betrayed his own values and sent his kids to private school. Given the reality he exposes in the documentary, one can hardly blame him.

One of the movie’s findings is that, over the past few decades, the money spent on public education in America has increased dramatically while the quality of education has plummeted. For example, according to the film, the money spent per pupil rose from $4,300 in 1971 to more than $9,000 today (figures adjusted for inflation). Yet, despite this enormous increase in funding, students’ reading and math scores have dropped significantly. The movie contends that 70 percent of eighth graders today cannot read at grade level and that, among thirty developed countries, the United States now ranks twenty-fifth in math and twenty-first in science.

The documentary identifies the teachers’ unions as one of the most significant causes of America’s education problems, and it is quite compelling in this regard. According to Guggenheim, teachers’ unions have one agenda: to keep teachers employed. He argues that good teachers make the crucial difference in our children’s educations, that bad teachers abound in the public schools, and that the main obstacle to ensuring that bad teachers are removed from schools and replaced with those who can teach are the teachers’ unions.

One of the biggest problems is the union-supported tenure system, which makes it nearly impossible for administrators to fire bad teachers. In one school district, a twenty-three-step process is required to fire a tenured teacher, and, if even one step is missed, the entire process has to start over again. The result, notes Guggenheim, is that more doctors and lawyers lose their professional licenses each year than do teachers.

What can school administrators do when they identify bad teachers and want to remove them from their schools? Very little. Because administrators effectively cannot fire bad teachers, they resort to options such as the “lemon dance,” in which one school trades its bad teachers for bad teachers being traded by other schools—in the hope that the bad teachers it receives will not be as bad as the ones it passes along.

Another option is to remove the bad teachers from the classroom without firing them. For instance, according to the documentary, the State of New York has a program whereby teachers on probation for a variety of charges—including sexual misconduct against students—are transferred from their teaching positions to a reassignment center where they await a hearing. These teachers stay in the so-called “rubber room” for an average of three years, all the while receiving full pay for doing nothing.

What of those who seek to change this abysmal system? Michelle Rhee, who was appointed acting chancellor of the Washington, D.C., school system in 2007—one of the worst in America—vowed to reform it. According to Ms. Rhee, “There’s a complete and utter lack of accountability for the job we’re supposed to be doing, which is: producing results for kids.” As the movie shows, she closed several failing schools in defiance of the system. In addition, Ms. Rhee proposed, among other things, that teachers be paid based on merit and that the union adopt a new contract that would enable teachers to achieve six-figure salaries if they gave up tenure and met certain standards. But the local union would not even allow a vote on the proposal. Rhee concluded: “Now I see why things are the way they are. It all becomes about the adults.” (Further concretizing this point, one parent recounts how in her childhood a teacher told her, “I get paid whether you learn or not.”)

Lest the teachers’ unions lose the power to block such attempts to reform their rigged system, they contribute vast amounts of money to sympathetic political candidates, who are unlikely to interfere with the status quo. In fact, according to the movie, teachers’ unions are the biggest contributor to political candidates in America today.

Fortunately, in the midst of this madness, some schools—most notably charter schools, several of which are profiled in the film—are able to skirt some of the system’s roadblocks to success and are producing laudable results.

Charter schools were established in the 1990s, and, although publicly funded, they function independent of the existing schooling system and thus are rarely subject to teachers’ union contracts, allowing them more freedom to hire and fire teachers and to develop their own curricula.

As the movie shows, parents in droves are trying to get their children into these schools—and with good reason. The movie examines the charter schools of the Knowledge Is Power Program (KIPP), which aims to improve education in poor neighborhoods. These schools tout longer school days, more individualized attention for students, and higher caliber teachers. And the results are telling: More than 90 percent of students from KIPP schools are ready for a four-year college at the time of graduation, demonstrating that good teachers and teaching methods can and do make a difference. Although the movie does not put it in these terms, by showing the difference between run-of-the-mill public schools and successful charter schools, it demonstrates that, to the extent education is freed of governmental restraints, marked improvements follow.

The most profound scenes in the movie are those in which children vie to gain a coveted spot in a charter school. By law, when more students apply to a charter school than it can accept, admittance is determined by a lottery. As obscene as it is for a government lottery to determine the fate of any child, viewers will be especially outraged to see the future education of fifth-grader Daisy—the most ambitious of the hopeful students profiled—being determined by the luck of the draw. If she does not win the lottery to get into KIPP’s LA Prep, the charter school in her district, she is doomed to attend a school with a 40 percent dropout rate, where she is likely to learn virtually nothing and, even if she does graduate, be ill prepared to attend a four-year college.

Despite its powerfully dramatic scenes, its justified damning of teachers’ unions, and its exposure of various horrifying aspects of the public school system, Waiting for “Superman” falls short in important respects. The film fails to address the more basic and most fundamental problems associated with public education. For instance, it never directly examines the perennial problem of public school curricula. Although it includes scenes that indicate the nonobjective nature of the content taught in public schools—such as one in which a student regurgitates the “fact” that European settlers of America “polluted the land” and the Indians “cleaned up after them”—the film never addresses why public school curricula invariably include such nonsense.

Further, although the film compares regular public schools to charter schools, it does not examine the alternative of private schools, which generally produce substantially better results than do public schools. Why not privatize the public schools? The question seems never to have occurred to Guggenheim. And although the movie encourages viewers to get involved in school reform, it offers no means to do so beyond suggesting, in the closing credits, that viewers sign up for text message alerts from an unspecified entity. Given the gravity of the issues raised in Waiting for “Superman,” the suggestion that impactful change will begin with text messages from someone-we-know-not-who is worse than a bad joke.

Adding absurdity to absurdity, in a bizarre attempt to have audiences “do something”—and almost as if to punctuate the lack of solutions offered by the documentary—the production and distribution companies involved with the film have partnered with DonorsChoose.org to offer each moviegoer a $15 coupon to donate to the public school of his choice.1 But these coupons contradict the very theme of the movie, which is that what schools need is not more money, but more freedom—especially freedom from the stranglehold of teachers’ unions.

The most fundamental flaw of Guggenheim’s documentary, however, is that he never returns to the moral questions he implicitly raises in the opening of the film. He claims he betrayed his own values by sending his kids to private school, but what were those values? Why did he hold them in the first place? And why did he betray them? If choosing to send his children to private schools was the right thing to do, shouldn’t all parents be free to make such choices for themselves? Don’t parents have a moral right to decide which schools are best for their children? And don’t Americans in general have a moral right not to fund an education system that they don’t choose to fund? Unfortunately, Guggenheim never explicitly raises, let alone answers, such questions.

Although Waiting for “Superman” exposes many problems with and horrors of American public education, it fails to address the fundamental problems that underlie these derivative issues. Nevertheless, this is an important documentary in that it illustrates the abysmal state of American public education and will spark debate about the need for change in an area where change is urgently needed.

You might also like

Endnotes

1 “How is DonorsChoose.org involved with Waiting for ‘Superman’?” DonorsChoose.org, http://help.donorschoose.org/app/answers/detail/a_id/278/~/how-is-donorschoose.org-involved-with-waiting-for-%22superman%22%3F.

![[TEST] The Objective Standard](https://test.theobjectivestandard.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/logo.png)