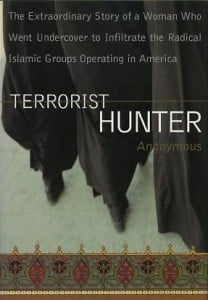

Terrorist Hunter: The Extraordinary Story of a Woman Who Went Undercover to Infiltrate the Radical Islamic Groups Operating in America, by Anonymous. New York: HarperCollins, 2003. 352 pp. $25.95 (hardcover).

In 2003, HarperCollins published Terrorist Hunter: The Extraordinary Story of a Woman Who Went Undercover to Infiltrate the Radical Islamic Groups Operating in America. The book is as relevant today, if not more.

At the beginning of Terrorist Hunter the anonymous author, since outed as Rita Katz, has infiltrated a conference for radical Muslims. She asks herself why she is in a place where she (and her unborn baby) will probably die if anyone finds her recording equipment. Recalling her past, she goes on to answer that question.

Katz was born into a wealthy family of Jews living in the then-prosperous Iraqi city of al-Basrah. Her happy childhood changed dramatically after Israel soundly defeated the Arab nations that attacked it in the Six-Day War of 1967. Unable to match Israel’s military power, many Arabs began to take revenge on the Jews within their own borders.

After the Ba’ath Party of Saddam Hussein and his cousin Ahmad Hassan al-Bakr seized power the year following the war, they came for Katz’s father, falsely accused him of being a traitor and a spy for Israel, and began torturing him to extract a confession. Meanwhile, Katz’s family was moved into a small, guard-surrounded stone hut from which her mother would leave each day to beg for her father’s release—and to which she would return with fresh bruises bestowed by her husband’s captors. Sadly, her valiant effort was in vain. Katz’s father was well known, and his trial was scheduled to be shown on television. The Iraqi tyrants were determined to quench their Arab citizens’ thirst for vengeance by reaching a guilty verdict.

Because no amount of torture had hitherto pushed Katz’s father to confess to the crimes he had not committed, Ba’ath party agents invited his pregnant wife into a room he knew well—one in which, just the day before, another prisoner’s wife was beaten and gang-raped by many guards. The agents told Katz’s father that, if he refused to confess, they would immediately walk into that room, cut open her belly, and bring his unborn child to him on a tray.

Later that evening he walked to the stand and “in a clear, unwavering voice, confessed his crimes as an Israeli spy and a traitor to the Iraqi nation” (p. 25). He was hanged soon thereafter in Baghdad’s central square—to the cheers of a half million Iraqis.

Katz goes on to tell the story of her family’s daring escape from Iraq, which required her mother to drug the guards with Valium bought surreptitiously and then pretend to be the wife of a general in order to get a car ride to a town where they could be smuggled to safety. The remainder of their trek to safety involved hiding in the secret compartment of a chicken truck and walking across mountains with duct tape on their mouths to ensure that nobody made a sound. All this is told with the drama of a good novel. In fact, when Katz and her family are on the plane to Israel, and her little brother musters the courage to ask if it is finally OK to tell people they are Jews, you are likely to cry—just as everyone on that plane did.

Given this heart-wrenching setup, the reader can easily understand why Katz would risk her life to stop terrorists from endangering America, her country of choice and the safest place she thought she could ever be. Unfortunately, one of the key takeaways from Katz’s book is that America is not safe—certainly not as safe as she once thought.

After moving to the United States, taking a job at a Middle East research institute, and picking up a Holy Land Foundation pamphlet on someone’s desk, Katz began to gain a more realistic understanding of militant Islamic activity in America. The message in the pamphlet, says Katz, was similar to the poison she thought she had escaped. “The surface is always cheap propaganda and innocence-splashed outer layers, but read between the lines and the true intent is vicious, venomous, tendentious” (p. 76). Because the pamphlet was written in both English and Arabic, Katz read both carefully, noting the differences between the two. After a couple of days, she reported her findings to her boss.

Among other things, Katz pointed out that thirty organizations were listed in English as having received funds from the Holy Land Foundation, whereas thirty-nine organizations were listed in Arabic. Among the nine omitted from the English translation, Katz discovered that one transferred funds to the families of Hamas terrorists who attacked Israeli citizens, that another “provided safehouses for terrorists,” and that yet another “was headed by one of the spiritual leaders for Hamas” (pp. 78–79). To her report, she added a note:

This is the summary of my findings of the illegal fund transfers by the HLF to Palestinian organizations involved in terrorism. I think that we should initiate a larger investigation based on this preliminary report. Please let me know your thoughts. (p. 79)

Katz’s boss agreed that a larger investigation was warranted, so she set to work.

Katz read anything and everything on or by those she suspected of supporting terrorism. She donned Muslim garb and went to fund-raisers for shady charities and to the mosques and conferences of radical believers. And she came to a stunning realization: The crowds that chanted “Death to America!” and “Death to the Jews!” were not only far away in the Middle East; they were also within America. Further, she found that terrorists were not only using places such as Afghanistan for safe havens; they were also hiding out in the United States.

She gives the example of Shallah Nafi, whose visa was sponsored by a professor at the University of South Florida. Nafi lived next door to the professor, joined the professor on the board of a “research institute,” and gave speeches at the Islamic Committee for Palestine conferences—until 1995 when the head of the Islamic Jihad Movement in Palestine (PIJ) was assassinated. At that point, Shallah promptly left for Syria and took over as secretary-general of the terrorist group. The professor claimed he was “shocked” (p. 93).

Katz documents how radical Muslims came to the United States for training, for instance, on how to fly planes. She also recounts activities in mosques such as Dar al-Hijra in Virginia, where she says imams openly preach hatred against the West and incite their followers to commit acts of treason against America. After hearing one speech at the mosque by Muhammad al-Hanooti in December 1998, Katz wonders:

How many people here really understood what was said . . . and how many supported these statements [cursing the Americans and wishing the Iraqi people victory over them]? No question as to where al-Hanooti’s loyalties lie, I thought as we all worshipped. Isn’t supporting an enemy publicly during wartime an act of treason? How far can the freedom of speech be stretched? Al-Hanooti urged his followers to collect money for the Iraqis. He called for jihad, holy war. He promised Allah’s curse on the “tyrannical Americans.” He urged his followers to make Dar al-Hijra the model for jihad. To me, that was nothing but a declaration of war against America, against the West, against civilization. . . . And we wonder now where Americans who went to train in Bin Laden’s camp ever got these crazy ideas of theirs. (pp. 110–11)

Following the money, Katz discovers that a dozen or so individuals connect hundreds of the charities and mosques that she has been tracking, that money jumps between these charities with dizzying speed, and that most of these organizations give their headquarters as the same address in Herndon, Virginia. It is here that Katz connects all the dots.

Katz discovers that those associated with the Herndon address have links to Hamas, PIJ, even al Qaeda, and she learns that the source of their funding is our so-called ally Saudi Arabia. Importantly, Katz shows this money trail: Readers who previously either discarded or too-quickly accepted the claim that Saudi oil money is bankrolling jihad across the world and in America will learn a lot.

This education comes with much frustration. Repeatedly, Katz relates how she shared the information she gathered with government agents—who either did nothing with it or were thwarted by the FBI in their attempts to pursue her leads. She discovers that the FBI has a maddening policy of gathering information and then doing absolutely nothing with it. In fact, says Katz, the FBI already had “smoking guns” on almost everything she herself uncovered, yet ignored these leads. Worse, according to Katz, the FBI tends to investigate the innocent with much greater speed and intensity than the guilty. When Katz learns that this applies to her, too, she is infuriated. “The bastards,” she says. “Terrorists and criminals are running around unimpeded and the FBI is investigating me!” (p. 235).

Thankfully, the book does not end before the charities Katz exposes as sponsors of terrorism finally have their assets frozen and are indicted for transferring funds to terrorist groups. And Katz acknowledges some positive steps that America took in the two years following September 11. But at book’s end she still is not particularly upbeat about our prospects. “As long as imams preach violence,” she says, “violence won’t be eradicated. . . . And as long as we call terrorist supporters [such as Saudi Arabia] ‘friends and allies,’ we are headed for disaster” (p. 333).

Unfortunately, owing to the subject matter of the book and that it was written anonymously, Terrorist Hunter lacks citations, so readers cannot confirm the accuracy of either her translations or her conversations with government officials. Additionally, Katz jumps from one time period to another throughout each chapter. This is sometimes used to dramatic effect and sometimes necessitated by the way the investigations unfold, but at times this jumping seems needless and is confusing. Finally, the lack of an index exacerbates these flaws, making it even harder for the reader to understand clearly which person or organization did and said what.

Despite its few flaws, however, Terrorist Hunter is a crucially important book. In showing how radical Muslims have operated on American soil, and in documenting the ineffectual response by our government to their activities, Katz’s book will be of value to anyone concerned with the fight against Islamic terrorists—which should be everyone.

![[TEST] The Objective Standard](https://test.theobjectivestandard.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/logo.png)