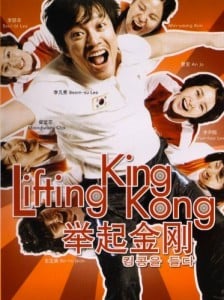

Lifting King Kong, directed by Park Geon-yong. Written by Bae Se-yeong, Park Geon-yong. Starring Lee Beom-soo, Jo An, Lee Yoon-hoi, Choi Moon-kyeong, Jeon Bo-mi, and Kim Min-yeong.

At t he beginning of Lifting King Kong, a South Korean film based on a true story, a weightlifter readies for his third attempt to lift 195 kilograms (429 pounds). As he walks onstage, viewers see the Seoul crowd waving their flags and cheering. But the man seems unaware. He closes his eyes, takes in a breath, and then—as he opens his eyes—breathes it out. He shakes his arms, appears ready, and with a scream, “Hyaa!,” steps to the barbell.

he beginning of Lifting King Kong, a South Korean film based on a true story, a weightlifter readies for his third attempt to lift 195 kilograms (429 pounds). As he walks onstage, viewers see the Seoul crowd waving their flags and cheering. But the man seems unaware. He closes his eyes, takes in a breath, and then—as he opens his eyes—breathes it out. He shakes his arms, appears ready, and with a scream, “Hyaa!,” steps to the barbell.

The weightlifter kneels down into a squat, places his hands on the bar around shoulder-width apart, and stops. “Hyaa!” He pushes up, sweeping the barbell as he stands and holding it at his collarbone, parallel with the ground. As he prepares to raise it above his head, the camera pans the crowd roaring their approval. The weightlifter squats a bit, the muscles in his neck drawn tight. Then, with a slight bounce, his left leg comes forward and his arms push the weight up until it balances triumphantly but precariously above his head.

Again, we see the crowd cheering like mad and hear his coach shouting, “You’ve got the gold!” But there’s a problem. His right foot seems to want to give. Again, his coach shouts encouragement: “You’re almost there Jibong! Just a little more!” But rather than his foot failing, Jibong’s left elbow does. The camera shows the barbell as it drops behind him, pulling him backward and onto the ground with it. The weightlifter screams in pain, looking to his left at his deformed elbow.

“This,” says a Korean announcer, “is a shocking and unfortunate turn of events.” As viewers watch medics rush the stage, he continues: “Korea’s top weightlifter, Lee Jibong, will unfortunately have to settle for bronze because of an injury.”

Things do not get much better for Jibong (played by Lee Beom-soo). In fact, they quickly get a lot worse. His elbow requires surgery. But much worse, he learns that his heart is overactive and he will have to give up lifting weights permanently. That means he will not get another chance for a gold medal; he is stuck with the bronze. It is a moving introduction to one of the movie’s main characters.

After the opening credits that follow, Lifting King Kong introduces the other main character. It is now 2008, twenty years after Jibong’s failed attempt at the gold, and another weightlifter lies facedown on a mat, receiving a massage.

“You should go to the hospital,” says the masseuse. “You can’t just ignore the pain.” The weightlifter responds, “I’d have to give up if I didn’t.” Continuing, the masseuse warns, “You could damage your back permanently like this . . . You lost your last competition because of your back. You can’t keep hiding this.” At that, the weightlifter swings around, says a few sharp words, and storms out.

Like Jibong, this weightlifter seems determined to take on any challenge—no matter the danger—saying at a press conference soon afterward, “I’m going to live up to the people’s expectations of gold.” But there is one big difference between this weightlifter and Jibong: this weightlifter is a young woman (played by Jo An).

As viewers soon learn, however, the two are connected. While walking toward the plane that will carry her to the Olympics in Beijing, a woman in the crowd calls out her name. “Youngja!” She hands Youngja a bag, saying she should open it on the plane and that it will give her strength. When Youngja does, she finds pictures of a group of young girls in tights, including herself, and their coach, none other than Lee Jibong. Also inside are Jibong’s bronze medal and a letter he wrote her.

All of the foregoing sets up the main storyline for Lifting King Kong, similar to something you have no doubt seen before. Jibong, for a time, was stuck handing out fliers on street corners to make a living. Ultimately, despite not liking children, he agrees to teach weightlifting to girls at a high school far out in the country.

As you might expect, the six girls who try out for the weightlifting team are social outcasts—with no apparent talent but with a willingness to try hard. As is usually the case in such movies, the group consists of a variety of personalities, each with unique strengths and challenges. One girl is smart; another “a little cuckoo.” One girl has a crush on a boy at school, providing a subplot; Youngja is an orphan, providing yet another.

Altogether, the group’s efforts change Jibong from a jaded athlete on the verge of alcoholism into a devoted coach who succeeds in training them. More importantly, their efforts toward weightlifting, winning the affection of their peers, and doing better in school, turn the girls into better, more confident versions of their former selves. If you like such turnaround stories—including their near-mandatory training montages—you will probably like this one, too.

However, Lifting King Kong can be harder on the viewer than other movies of its kind. The bullying from other students, for example, is graphic. And later, when another coach takes Jibong’s place and begins to train the girls, you will see him repeatedly smack and berate them. Such parts are truly disturbing even if they do make clear the inner character of these girls and ultimately dramatize the movie’s theme, which Jibong expresses in a short conversation with Youngja near the movie’s end.

Unsure about an upcoming competition, and crying, Youngja calls her former coach: “I haven’t been feeling good and I don’t think I can get the gold,” she says. “Maybe I should drop out of the competition?” Jibong replies: “Youngja, everybody tries to win the gold. But just because you win the bronze, it doesn’t mean your life will be a bronze medal life. If you try your best and don’t give up, you’ll have a gold medal life.”

Of course, Youngja does not give up. Along with the other girls, she soldiers on. And she comes to agree with Jibong that “although the results may not always reflect your efforts, working as hard as you can to achieve your goal is priceless.”

This attitude ultimately leads Youngja to the 2008 Olympics, and to the final scene in which she, like Jibong at the film’s outset, is on her third attempt to lift a daunting amount of weight and win the gold. So much emotional power is packed into this particular scene that it’s almost explosive. This is in part because of a major event that occurred in the previous scene and in part because of the parallels between Youngja’s situation and Jibong’s at the movie’s start. In any case, this final scene nails the theme of the movie in a way that is likely to surprise you at first, then stick with you and motivate you ever after—regardless of your own personal goals.

It would be too much to praise Lifting King Kong as a great or original movie. But it is a good movie, and, in executing its simple theme well, it is well worth watching.

![[TEST] The Objective Standard](https://test.theobjectivestandard.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/logo.png)