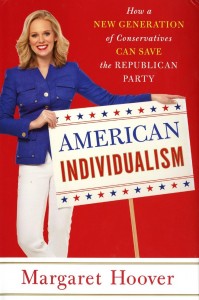

American Individualism—How a New Generation of Conservatives Can Save the Republican Party, by Margaret Hoover. New York: Crown Forum, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc. 247 pp. $24.99 (hardcover).

While working on the 2004 Bush-Cheney reelection campaign team, Fox News contributor Margaret Hoover came to a stark realization: On gay rights, reproductive freedom, immigration, and environmentalism, the Republican party “was falling seriously out of step with a rising generation of Americans . . . the ‘millennials’” (pp. ix, x). “[B]orn roughly between the years 1980 and 1999 [and] 50 million strong,” this rising new voter block, says Hoover, has “yet to solidly commit to a political party” and thus could hold the key to the GOP’s electoral future (p. xi).

Hoover looks back for comparison to 1980, when Ronald Reagan fused a coalition of diverse conservative “tribes” around a central theme: anticommunism (p. 25). If the millennials, who “demonstrate decidedly conservative tendencies” (p. xii), could be united with today’s conservatives under “a new kind of fusionism” (p. 41), the Republican party would be on its way to majority status, she holds.

Hoover sees differences among conservatives and divides the “organized modern conservative coalition in America” (p. 28) into three main categories:

- economic libertarians and fiscal conservatives led by three “leading lights” who “were . . . not populists [nor] self-described conservatives,” but “thinkers”—Friedrich von Hayek, Milton Friedman, and Ayn Rand.

- social conservatives, traditionalists, and the “Religious Right” led early on by Russell Kirk, Richard Weaver, and Robert Novak, and later by Jerry Falwell, Pat Robertson, James Dobson, and Phyllis Schlafly.

- anticommunists and paleocons led by Whittaker Chambers, John Chamberlain, James Burnham, and Pat Buchanan.

According to Hoover, these three factions have formed the core of the movement that began with the publication of the National Review in November 1955 (p. 28) and have since been joined by neocons (p. 35), Rush Limbaugh’s “Dittoheads,” Sarah Palin’s “Mama Grizzlies,” the Tea Party uprising (pp. 36–37), and the “Crunchy Cons” and “enviro-cons” (p. 37). Hoover’s hope is to find common ground between these conservatives and the millennials.

In the introduction and in chapter 3, Hoover identifies millennials broadly as “likely to call themselves liberal,” yet “not proponents of the big-government orthodoxy of modern liberalism.” She says they “cherish individual freedom,” “have favorable attitudes toward business and individual entrepreneurship,” and lean toward being “fiscally conservative but socially liberal” (pp. xi–xii)—but still “have significant faith in the power and ability of government to do good” (p. 56). Although the millennials voted heavily for Obama in 2008, they retreated from the Democrats in 2010 and, says Hoover, are “ripe for a political party to come along and make the case for maximum freedom, fiscal responsibility, equality of opportunity, social mobility, individual responsibility, and service to the community and country” (p. xii).

What could unite conservatives and millennials and thus rescue the GOP from remaining “at best a minority party—or worse, [fading] into irrelevance” (p. x)? Hoover believes the answer lies within her great-grandfather’s 1922 book, American Individualism. In that book, Herbert Hoover, who would become our 31st president, challenged the rising tide of early 20th-century socialism and its variants with an impassioned defense of America’s unique strength, “its [cultural and political] celebration of the individual” (pp. 206–7).

Inspired by Herbert Hoover’s American Individualism, her 2004 political stint, and other personal experiences, Margaret Hoover presents a political strategy for uniting conservatives and millennials in her own American Individualism, this one subtitled How a New Generation of Conservatives Can Save the Republican Party. The title speaks to the supreme importance Hoover places in the political philosophy presented in her great-grandfather’s 1922 manifesto. “By invoking the principles of American individualism,” she writes in the introduction, “we have a template for addressing the challenges of the twenty-first century in a way that can make modern conservatism relevant for the rising generation” (p. xv). Using that template, Hoover proposes a GOP platform anchored to a central abstract principle, which she characterizes (in various ways) as “individualism tempered by responsibility to the community” (p. 25).

In chapters 4–12, Hoover outlines a new Republican platform in nine key areas; government spending and entitlements, marriage equality, education, feminism, abortion, environmentalism, immigration and border security, national defense, and foreign policy. The general theme: The GOP must promote “American Exceptionalism, [a] system . . . unique in its emphasis on individual liberty” (p. 210, her emphasis) both domestically and throughout the world.

On the domestic front, Hoover advocates personal Social Security accounts and Health Savings Accounts (p. 65); enabling all parents “to vote with their feet [by supporting] every effort to open up the school system to competition,” including “charter schools and . . . magnet programs that focus on special curricula and even voucher systems that allow parents to move their tax dollars to the school of their choice” (p. 123); and other “free market solutions” to problems we face. She advocates leaving the welfare state’s basic “safety net” in place—“government has a role to play in meeting certain social needs,” she writes—but says “that individuals are ultimately responsible for their lives, and must be trusted and encouraged [generally through voluntary private initiatives “based on the free choices of individuals rather than the dictates of government,” (p. 51)] to look out for themselves, help others in need (pp. 63–64), [and] participat[e] in the community” (p. 51).

[T]he individual, rather than the government, must take the lead in addressing the problems of society and community. Liberals tend to believe that the best social improvements emanate from government, but in fact most of the great reforms have sprung from the individual minds of men and women acting alone or in concert with one another, oftentimes co-operating under the auspices of . . . volunteer-based social, . . . civic or economic organizations. (p. 51)

She also advocates expanding legal immigration (p. 185) and providing a path to citizenship for current illegals (pp. 181, 188) after first “securing our borders” (p. 181). Generally speaking, she advocates (albeit imperfectly) moving toward a larger degree of individual choice and less government planning.

In the realm of foreign policy, Hoover advocates a “strong military” (p. 216); support for “those countries that share our values” (e.g., by providing missile defense systems); abandoning efforts to “reach out to hostile, rogue nations such as Iran and North Korea, or aggressive nations like Russia” (p. 217); and advancing “free trade and open markets” (p. 219). And, says Hoover, our national defense policy should recognize that terrorism is not the primary enemy, but rather a “tactic” of “Islamist Supremacy,” an “ongoing movement, . . . the most violent ideology of the twenty-first century so far—an ideology as sweeping and murderous as fascism and communism” (p. 193).

Perhaps most notably, Hoover advocates expunging the social agenda of the Religious Right from the Republican platform. In chapters 5 and 8, she passionately makes her case for marriage equality for gays and lesbians (“Freedom means freedom for everyone,” she declares, quoting Vice President Dick Cheney [p. 98]); and abortion rights for women in the first and second trimesters (“this is an individual decision among a woman, her family, her doctor, and her God, not the government” [p. 147]), noting that consistency on this and other social issues is vital to the credibility of the conservatives’ traditional support for individual freedom (pp. 66–67). As it stands, says Hoover, “The Republican Party’s brand is damaged [because of the] perception that the Religious Right and social conservatives dominate the party apparatus (p. xiii).” That perception is largely accurate, she argues, but can be changed for the better by fusing social and economic freedom.

Indeed, a Republican party that adopted such a platform would be more effective and its candidates more electable because they would be closer to consistent in defending an individual’s right to life, liberty, property, and the pursuit of happiness. But how consistently they would defend these rights depends on their more fundamental ideas. What exactly does Hoover mean by “American individualism,” by “individualism tempered by responsibility to the community,” and how does this idea support or conflict with her policy positions?

To answer that question, it is instructive to turn to her acknowledged inspiration. In his 1922 book, Herbert Hoover is often eloquent in characterizing individualism. “[I]ntelligence, character, courage . . . the divine spark of the human soul . . . [and] production both of mind and hand do not lie in agreements, in organizations, in institutions, in masses, or in groups,” but “are alone the property of individuals.” Yet he holds:

Individualism cannot be maintained as the foundation of a society if it looks to only legalistic justice based upon contracts, property, and political equality. . . . We have learned that the impulse of production can only be maintained at a high pitch if there is a fair division of the product, [which] can only be obtained by certain restrictions on the strong and the dominant [and] the embracement of the necessity of a greater and broader sense of service and responsibility to others as a part of individualism. . . .1

[N]o civilization could be built or can endure solely upon the groundwork of unrestrained and unintelligent self-interest. The problem of the world is to restrain the destructive instincts while strengthening and enlarging those of altruistic character and constructive impulse for thus we build for the future.2

In other words: “Individualism” must be restrained by selfless service to others.

Herbert Hoover does not ground his defense of the individual in rational self-interest. His moral ideal is altruism, but he holds that mankind is not ready for this ideal and that, until it is, individualism has a part to play.

Yet true as this is, the day has not arrived when any economic or social system will function and last if founded upon altruism alone.

With the growth of ideals through education, with the higher realization of freedom, of justice, of humanity, of service, the selfish impulses become less and less dominant, and if we ever reach the millennium, they will disappear in the aspiration and satisfactions of pure altruism. But for the next several generations we dare not abandon self-interest as a motive force to leadership and to production, lest we die.3

This is the core meaning of Herbert Hoover’s “American individualism”—an “individualism” that serves altruistic ends. And this is the same foundation on which Margaret Hoover bases her version of it.

Hoover does a respectable job of making her abstract political case for a consistent GOP platform oriented around individualism despite this contradictory premise. But by following her great grandfather and adhering to conventionally accepted ethical standards—in her words, “the virtues of service and sacrifice” to the “community” (p. 63)—as a defining characteristic of moral action, she fails to fully uphold the individual’s moral right to his own life; thus she undercuts her promotion of his political right to chart the course of his own life. Although Hoover grants that the first on the list of “several components to individual liberty” is “the moral component: the ability of the individual to make moral choices on his or her own behalf” (p. 50), her acceptance of the propriety of sacrifice for the community undermines her whole case and leads her to mix such things as “individual responsibility” and “service to the community and country.”

Owing to this contradiction, it is no wonder that, politically, Hoover leaves the door wide open to rights-violating policies and statism. For example, she concedes that “government oversight [must ensure] a way to save for retirement and a way for the poor to pay for their healthcare, principles that the New Deal and Great Society programs introduced. . . . The question that surrounds these programs today has to do with their size,” not their legitimacy (pp. 64–65). In her otherwise laudable foreign policy she advocates using taxpayer dollars to fund extensive humanitarian foreign aid, such as HIV/AIDS relief in Africa (pp. 218–19). And she echoes her great-grandfather’s disapproval of laissez-faire policies and affirms his belief in “a vigorous—but limited—role for government to play” (p. 12). In the abstract, she seeks to mold the Republican agenda into a consistent platform of individual liberty, but in reality—due to the unfortunate corrupting influence of altruism—she necessarily falls short.

What is the net effect of Hoover’s approach? Is it ultimately just another self-defeating conservative concession to altruism and thus to statism? Or is it a step by a conservative in the right direction, toward a fully free capitalist society? I view it as the latter.

Hoover’s main emphasis is individualism, and politically her sympathies clearly lie with individual freedom. Her calls for “Republicans . . . to be more philosophically consistent” and to “pledge themselves to the virtue of individual choice applied broadly” (p. 66, her emphasis) is a breath of fresh air coming from a conservative. She recognizes the contradiction of advocating school choice for one’s children but not the full freedom to choose one’s spouse, or of having more choice over one’s health-care dollars but not over one’s own body. Although Hoover does not seem to fully understand—and certainly does not make the case for—the moral foundation for individualism, and although she contradicts this political ideal at times, her call for consistency to this standard is a substantially better approach than that of a typical conservative.

Advocates of freedom and capitalism should champion Hoover’s embrace of individualism as an ideal, and we should do what we can to help her and like-minded people see the need and nature of the principles on which individualism depends (i.e., those of rational egoism and, more broadly, Ayn Rand’s philosophy of Objectivism).

General support for individualism as the American political ideal is simultaneously a means to a better political environment in the short term and to greater opportunities to make the case for the deeper principles. Imagine a GOP with the explicit banner “American Individualism” firmly planted atop its political platform. This would greatly expand the opportunity for truly consistent champions of individualism to enter the mainstream of political dialogue. It could explicitly redefine American politics as a clash between individualism and collectivism, compelling Republicans toward consistency in defense of freedom while painting Democrats into a collectivist corner. And within both the Republican party and in the country at large, it could infuse U.S. politics with a badly needed debate on individual rights, the proper role of government, and the deeper moral principles at play.

Despite its flaws, Margaret Hoover’s American Individualism is a step by a conservative toward genuine liberty and an opportunity for capitalists to change the terms of the debate for the better.

You might also like

Endnotes

1 American Individualism, ch. 1: “American Individualism,” http://www.hooverassociation.org/hoover/americanindv/american_individualism_chapter.php. I found no evidence to indicate that Ms. Hoover disagrees with any part of Herbert’s political philosophy. Her speech to the Herbert Hoover Presidential Library Association, in which she glowingly endorses her great-grandfather’s philosophy, can be found at http://www.hooverassociation.org/hoover/americanindv/american_individualism_by_margaret_hoover.php.

2 American Individualism, ch. 2, “Philosophic Grounds,” http://www.hooverassociation.org/hoover/americanindv/philosophic_grounds.php.

3 American Individualism, “Philosophic Grounds.”

![[TEST] The Objective Standard](https://test.theobjectivestandard.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/logo.png)