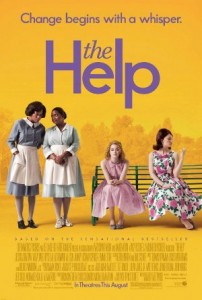

The Help, written and directed by Tate Taylor. Starring Emma Stone, Viola Davis, Bryce Dallas Howard, Octavia Spencer, Jessica Chastain, Allison Janney, and Sissy Spacek. Distributed by DreamWorks SKG. Rated PG-13 for thematic material.

Only a handful of fictional films—among them, To Kill a Mockingbird and In the Heat of the Night—have successfully addressed the ugly realities of racism in 20th-century America in compelling, dramatic ways. Tate Taylor’s The Help can be added to this list.

Set in the deeply segregated Mississippi of 1963, The Help is, on one level, about a young, privileged white woman’s attempts to become a professional writer. Skeeter Phelan, played by Emma Stone, is the daughter of an old, wealthy, socially connected white family in Jackson, Mississippi. After graduating from Ole Miss with an English degree, Skeeter has come home, hoping to pursue her dream of writing literature, taking her first step by writing the housekeeping column for the local paper. Skeeter’s career choice is diametrically opposed to those of her lifelong friends and the rest of the Junior League who, at twenty-three, have already settled down and begun having babies. Led by Hilly Holbrook (Bryce Dallas Howard), these would-be Scarlett O’Haras are supported by “the help” of the title, black housekeepers who do the cleaning, shopping, cooking, and, most critically, raising generation after generation of white children, yet are not even allowed to use their employers’ bathrooms.

While writing her column, Skeeter seeks the assistance of Abileen Clark (Viola Davis), the black maid of one of her friends. In so doing, she sees for the first time the ugliness that underlies the system in which she has lived her entire life. Here the story turns to deeper matters and the theme of independence versus conformity.

Writer/director Taylor contrasts Skeeter’s iconoclasm, which enables her to write the story of “the help” at the same time that Mississippi and the rest of the South are rocked by the upheavals of the nascent civil rights movement, with the social conformity that enables and fuels the institutionalized racism. The film also presents a crucial truth about the plight of the black housekeepers. Some have better employers, some worse, but all are essentially stuck—trapped in a social order all too similar to the slavery their grandparents had escaped barely a century before. (One housekeeper is actually “willed” to her employer’s children when the employer dies.)

The proponents of racism on which the film focuses are not stereotypical beer-swilling, tobacco-chewing Klan rednecks, but the Junior League beauties of Jackson. The focus on the casual, institutionalized racism these young housewives accept and perpetuate depicts injustices that are, in some ways, even uglier than what one might expect from Klansmen.

Bryce Dallas Howard delivers one of her best performances as Hilly, the symbol of white racist society, portraying how evil ideas can twist a human soul. Hilly operates under the unswerving belief that she is in the right, is preserving her way of life, and is acting out of Christian kindness. Her self-righteousness is the root of her power, and Skeeter and the other Junior Leaguers follow her lead in spite of their obvious personal misgivings—shown in their occasional hesitation or halfhearted acceptance of Hilly’s pronouncements.

On the other end of the moral spectrum is Abileen. The film is ultimately her story and she narrates most of the action. Her final confrontation with Hilly is psychologically powerful: a clash of ideas—individualism versus conformity—more moving than any physical confrontation ever could be. Abileen wins, but at heavy personal cost (her pyrrhic victory, however, is tinged with hope).

The Help avoids the clichés commonly found in films dealing with social problems. The racists don’t see the light and, although the first cracks in its foundations have appeared, the system doesn’t dissolve in front of our eyes. The audience may know the history of the decades that were to follow, but the characters do not. The future, in their eyes, is uncertain; and that they take what are, in fact, life-and-death risks throughout the film is inspiring and harrowing at times.

The film’s touches of humor help to break the tension somewhat, but even an offhand joke or the comeuppance of a racist employer is tinged with a dark undercurrent present throughout the picture. Jackson, Mississippi, was a dangerous place to be if you were black, and we are reminded of this constantly—an extra in the background might be scrutinizing a conversation between a white and a black woman a little too closely, a policeman might be mistreating a black person, and, always, “the help” are aware that they are employed only on the sufferance and whim of employers who do not care a whit about the lives of those whom they consider to be second-class citizens at best.

Skeeter’s story is the least interesting in the film but nevertheless admirable. Emma Stone has proven herself to be a capable and engaging actress—and her performance here is spot on—but the societal pressures her character is facing (marriage, motherhood, and career) are solved rather easily. And they should be: Being white and wealthy in Jackson meant one had many options and choices. More interesting is how she confronts the issues of racism in her own home, including a tragic story about the maid who raised her. A still more interesting subplot involves the ostracized wife (Jessica Chastain) of the scion of a local family who, unlike Skeeter, does not have the connections, education, or confidence to overcome the societal prejudice at the hands of the Junior League. But none of these subplots—which, incidentally, contribute to the film’s excessive length, at two hours and twenty minutes—is as interesting or compelling as the story of Abileen and her fellow maids.

Ultimately what makes the film work is that Taylor tells an intimate story about ordinary people caught in the web of institutionalized racism. We identify with all of the characters thanks to the excellent work of the cast. There is some naturalism in the dialogue, but there is philosophical depth underpinning it. These maids are taking a principled stand for their rights, making it clear that they know what’s at stake, without whining or complaining. And, refreshingly, Director Taylor relies on his characters actions to make their most compelling points and expressions of defiance, ranging from sneaking in to use an off-limits bathroom to baking a particularly well-deserved form of vengeance.

The Help may be one of the best films in recent memory about racism, and it certainly is one of the best films of the year.

![[TEST] The Objective Standard](https://test.theobjectivestandard.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/logo.png)