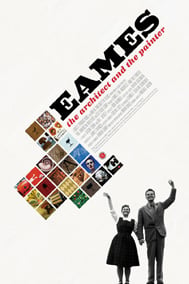

Eames: The Architect and the Painter, directed by Jason Cohn and Bill Jersey. Written by Jason Cohn. Narrated by James Franco. Released by First Run Features (2011). 84 minutes (unrated).

Eames: The Architect and the Painter, of the PBS American Masters series, presents a portrait of the husband and wife design team of Charles and Ray Eames. Charles, educated as an architect, and Ray, trained as a painter, met in 1940 at the Cranbrook Academy of Art in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan. Although Charles was already married at the time, he fell madly in love with Ray, ended his marriage, and proposed to her. After marrying, they left the Midwest and moved to Los Angeles with the goal of bringing to fruition Charles’s vision for the molded plywood chair, which had already won a major award but needed further development. There they founded the Eames Office, which was by all accounts informal, playful, and circus-like, yet simultaneously focused and intense. “[L]ife was fun was work was fun was life” as former Eames Office designer Deborah Sussman describes it in the film.

The Eames Office became a launching pad that propelled design after successful, groundbreaking design onto the postwar American scene. Most commonly recognized today for its Herman Miller-produced plywood- and fiberglass-shell chairs, the Eames Office produced a wide range of furniture designs over the years, as well as an array of other products, including molded plywood military splints, toys, textiles, photography, graphic design, educational films, and elaborate exhibition designs. Told through film clips, stills, letters, interviews, and narration, this engaging documentary film manages to take their incredibly prolific working life of nearly forty years and compress it into eighty-four fascinating minutes.

Rather than proceeding in strictly chronological order, the film examines the Eames’ life and work by general subject matter: their chair designs and early life together; the design and construction of their home, Case Study House #8 (from the magazine Arts and Architecture’s “Case Study Houses” program); the first experimental and, later, educational films they made; Charles and Ray’s strained relationship in their later years, including Charles’s affair with art historian and filmmaker Judith Wechsler (which their collaborative work-life survived); their last projects together; and Ray’s final ten years (exactly, to the day) after Charles’s death in 1978.

This approach by the filmmakers weaves a broadly chronological and sufficiently coherent narrative arc, but may lead some viewers to miss the fact that many of these activities, described separately in the film, occurred simultaneously. For instance, furniture design didn’t cease when the Eameses began experimenting with short film production in the 1950s; it continued alongside film and other new activities as the office grew. This is worth bearing in mind while watching, because the productive output of the Eames Office is all the more astonishing when one realizes the degree to which a wide range of products were simultaneously developed there, an extraordinary percentage of which were highly successful or even groundbreaking masterpieces.

As the story of Charles and Ray (who often were and are assumed to be brothers) unfolds, we witness a vintage 1956 TV clip from The Arlene Francis Home Show in which Francis struggles to figure out what to make of Mrs. Eames’s appearance on the show as Charles’s business partner. The studio is filled with examples of then already well-known Eames furniture: different versions of the original plywood chair that started it all; examples of their brightly colored fiberglass shell chairs; the welded wire chair with its signature bikini cover; and others. As she interviews them for the debut unveiling of the now-classic Eames Lounge Chair and Ottoman, she tries her best to understand their unorthodox working relationship, both for herself and her viewers, but is clearly puzzled by it. The brief interview clip (also available on YouTube in its entirety) is as much a time capsule of postwar American culture in general (gender attitudes and all) as it is a document of Charles and Ray’s cultural ubiquity during that period.

We are shown how, with the 1949 construction of their own house, Charles and Ray were able to fully integrate their home and work lives. Made entirely of off-the-shelf industrial components, the house was both a product of their design philosophy and another instant icon of modern design. However, the house also represented something greater than this: It was a crucial achievement on a fundamental, personal level for Charles and Ray that enhanced their relationship to their work. The activity of the Eames Office was, by all accounts, notoriously intense, fast-paced, and somewhat relentless. When Charles and Ray left the office at the end of the day and went home to recuperate and ready themselves for the following day’s work, they would segue from the unique aesthetic experience that was their work environment to a similarly unique and personalized experience in their home environment, both of which were based on their own fundamental aesthetic values.

This total integration of their personal and work lives is superbly illustrated in one of the outtakes, available both on the DVD release and online. The clip (titled “Having Fun” online and “What do you do for fun?” on the DVD release) depicts an interviewer asking Ray Eames what they do “for fun, to enjoy yourselves.” Ray’s answer, after stammering and trying to think of something:

We, ah, try to find time to do all the things we want to do, and that’s as much enjoyment, I think, as is, is possible . . . if there was a moment to, to take pictures . . . to continue something we hadn’t been able to touch all day, but the days are not long enough to enjoy ourselves, quote.

Other than describe the work they do on their various projects, Ray is extremely hard put to come up with anything at all, outside their work, that they would consider “fun” or “enjoyable” by the typical application of such terms. In the end, even after stopping the interview and starting her answer again, she is so befuddled by the whole thing that all she can manage is to playfully mock the poor interviewer’s question.

Throughout the film, we are presented with memorable quips, quotes, and slogans (attributed mainly to Charles) that display the intensity of their passion for both life and work and emphasize the degree to which the two were intertwined. “Take your pleasure seriously,” a well-known Eames quote, heads a segment of the film that begins with the entire Eames Office staff running out, cameras in hand, to photograph the newly-arrived Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus. The circus fascinated Charles and inspired the informal, play-with-your-work approach of the Eames Office. The discussion then segues into the experimental films they began making in the 1950s, and how this work ultimately led to the Eames Office being contacted by the U.S. Information Agency to make a film describing life in the United States for the 1959 American National Exhibition in Moscow. That project became Glimpses of the USA. More than just a film about American life, Glimpses turned, at the hands of Charles and Ray, into a seven-screen multimedia extravaganza. It was a huge success, and further galvanized their reputation as expert communicators of big, complex ideas to mass audiences. As their reputation grew, so did their roster of corporate clients, to include the likes of Westinghouse, Boeing, Polaroid, Alcoa, and, most famously, IBM.

When examining the work of any designer, it is instructive to ask the question: What, exactly, are the problems this designer has set out to solve? The problem the Eameses confronted in their work was not simply “the design of a chair” or “the production of an educational film” or any particular, concrete thing that they happened to create. It was to make, in Charles’s words, “the best, for the most, for the least.” This theme appears throughout the film as a dearly held ideal that underpinned all of Charles and Ray’s designs. Early on, this is illustrated by the use of industrial-scale mass production to affordably bring a new concept in chairs and other furnishings to a wide public. Later, the Eames Office would use film, exhibitions, and mass media to bring ideas, in addition to home furnishings, to a wide audience.

Charles Eames excelled at distilling broad, abstract concepts and complex design problems to their essentials and communicating them clearly, such that anyone could understand them. This ability, leveraged by Ray’s uncanny visual sensibility, allowed the Eames Office to produce unprecedented results and achieve spectacular success. During a segment of the film discussing the Eames short film “Tops,” former Eames Office designer Jeannine Oppewall, now an Academy Award-nominated production designer, characterizes one of the keys to their success in this way: “Many designers were, and still are, happy with the manipulation of objects. He [Charles] was only truly, deeply, happy manipulating an idea.”

An impression emerges of Charles as the front man and technical genius, directing the Big Picture and guiding the overall process with Ray as the indispensable aesthetic genius, shaping the visual, color, and detail aspects of their work together. However, it is repeated time and again throughout the film in interviews with those who knew and worked with them that it is very difficult to separate the individual influences of Charles and Ray on their work. As an archivist at the Library of Congress (the repository of the Eames Office archives) explains in an interview, “It’s as if they were one individual, with two different special areas . . . but separating them isn’t the important part, it was what they created together—that’s why it’s so good.”

Eames: The Architect and the Painter is a brief but rich glimpse into a forty-odd-year-long design process by which a pair of bold visionaries continuously and consciously shaped American culture. The interviews are thought provoking and insightful, and the narrative is instructive without being pedantic, even if a bit dry. (Narrator James Franco, it would seem, could learn a thing or two from Charles and Ray’s example of injecting fun into one’s work.) Those already familiar with Charles and Ray Eames’s work are quite likely to learn a new thing or two about them from this presentation, and even learned fans will enjoy the ample film and audio footage of Charles and Ray in action and doing the thing designers do best: remaking the world around them to suit their vision of how things should be.

The film in its entirety, along with the outtakes (many of which are as enjoyable as the film itself) can be watched online at pbs.org/wnet/americanmasters/, and is also available on DVD from First Run Features.

Disclosure: This reviewer owns a set of Eames fiberglass shell chairs, and was sitting in one, with his feet occasionally propped in another, while watching the film and writing this review.

![[TEST] The Objective Standard](https://test.theobjectivestandard.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/logo.png)