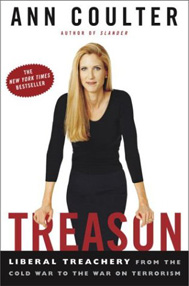

Treason: Liberal Treachery from the Cold War to the War on Terrorism, by Ann Coulter. New York: Crown Forum, 2003. 368 pp. $11.99 (hardcover).

In Treason, Ann Coulter chronicles the anti-American actions of the leftist “liberals” in the United States from the Cold War to the beginning of the “War on Terrorism.” However, the book concentrates primarily on the Cold War, and fortunately so, as this is where Coulter shines.

Among other things, Coulter informs us about Soviet espionage and treachery in the Democratic administrations of Roosevelt and Truman, the injustice done to Joe McCarthy, and the Venona Project—a series of Soviet cables declassified in the 1990s.

The Venona Project was begun in 1943 by Colonel Carter Clarke, chief of the U.S. Army’s Special Branch, in response to rumors that Stalin was negotiating a separate peace with Hitler. Only a few years earlier, the world had been staggered by the Hitler-Stalin Pact. . . . Colonel Clarke did not share President Roosevelt’s trust in the man FDR called “Uncle Joe.” Cloaked in secrecy, Clarke set up a special Army unit to break the Soviet code. Neither President Roosevelt nor President Truman was told about the Venona Project. This was a matter of vital national security: The Democrats could not be trusted. (p. 36)

Coulter shows that both FDR and Truman repeatedly attempted to thwart investigations of Soviet espionage in their administrations, while ignoring any evidence that came through.

FDR “gave strict orders that the OSS [a precursor to the CIA] engage in no espionage against the country ruled by his pal, Uncle Joe” (p. 34). And an official in the Roosevelt White House reaffirmed this stance and told the army to stop its “code-breaking” activities, which luckily, “The head of the Venona Project ignored” (p. 46). Although FDR was repeatedly warned about Soviet spy Alger Hiss—a high-level official in the State Department—he repeatedly ignored the evidence and even told one official who warned him “to go f--- himself” (p. 18). At the end of the day, FDR took no action against Hiss. “To the contrary, Roosevelt promoted Hiss to the position of trusted aide who would go on to advise him at Yalta . . . where Roosevelt notoriously handed over Poland to Stalin” (pp. 18–27).

For his part, Truman would crusade against the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) and Joe McCarthy’s investigations of communist spies while praising Stalin, saying things such as “I like old Joe” (p. 44), and that Joe was “a fine man who wanted to do the right thing” (p. 148). In fact, after Winston Churchill criticized communism in the “Iron Curtain” speech he delivered in Fulton, Missouri, Truman rebuffed Churchill, “apologized to Stalin and invited him to the United States for a rebuttal speech. He graciously offered the murderer the services of the U.S.S. Missouri for the trip” (p. 148).

Says Coulter of all the above, “The problem was not that Democrats were not given sufficient proof of Communist spies in their administration. It was that they didn’t give a damn” (p. 46). Eisenhower’s attorney general, Herbert Brownell, would eventually accuse Truman of knowingly appointing a communist spy, Harry Dexter White, to the International Monetary Fund (IMF). “Truman responded to Brownell’s statement by indignantly denying he had ever seen an FBI report suggesting that White was a spy. The FBI then produced the report” (pp. 45–46).

Treason vindicates Senator Joe McCarthy. “Soviet spies in the government were not a figment of right-wing imaginations. McCarthy was not tilting at windmills. He was tilting at an authentic Communist conspiracy that had been laughed off by the Democratic Party” (p. 11). “The idea that there was nothing going on and McCarthy burst onto the scene like the Terminator is preposterous” (p. 32).

Only a small number of intercepted Soviet cables have been decoded. But even that much proves McCarthy was absolutely right in his paramount charge: The U.S. government had a major Communist infestation problem. . . . America had been invaded by a civilian army loyal to a hostile power. . . . Soviet operatives were stealing technical information from atomic, military, radar, aerospace, and rocket programs. (p. 37)

Among the most notorious Soviet spies in high-level positions in the Roosevelt and Truman administration—now proved absolutely, beyond question by the Soviet cables—were Alger Hiss at the State Department; Harry Dexter White, assistant secretary of the Treasury Department, later appointed to the International Monetary Fund by President Truman; Lauchlin Currie, personal assistant to President Roosevelt and White House liaison to the State Department under both Roosevelt and Truman; Laurence Duggan, head of the Latin American desk at the State Department; Frank Coe, U.S. representative of the International Monetary Fund; Solomon Adler, senior Treasury Department official; Klaus Fuchs, top atomic scientist; and Duncan Lee, senior aide to the OSS. (p. 44)

A high point in Treason is Coulter’s dismissal of the famous “have you no decency” speech that Attorney Joseph Welch delivered against McCarthy during the Army-McCarthy hearings. Coulter provides the proper context of the situation. At the time, Attorney Welch was weeping over McCarthy’s factual statement that a lawyer in Welch’s own law firm once belonged to the pro-communist National Lawyers Guild. Welch accused McCarthy of destroying his employee’s name with the revelation: “Until this moment, Senator, I think I never really gauged your cruelty or your recklessness. . . . Little did I dream you could be so reckless and cruel as to do injury to that lad.” But, as Coulter shows, Welch’s outrage was anything but sincere, given that months earlier Welch himself had told the New York Times about his employee’s affiliation with the “legal mouthpiece of the Communist Party” (p. 114). This is just one of many untruths pertaining to McCarthy and the hearings that Coulter corrects.

Unfortunately, McCarthy’s vindication never came in his time; Coulter also shows how McCarthy’s career and name were dragged through the mud. “The primary victim of outrageous persecution during the McCarthy era was McCarthy” (p. 104). Coulter vividly describes the attacks on McCarthy. The Democrats and the media relentlessly harassed McCarthy for the sole “sin” of investigating Soviet spies. And to a large extent, the left succeeded in cutting down “a brave man” and creating the illusion that zealots such as McCarthy were unjustly harassing innocent and well-intentioned Americans (p. 71). “Through the left’s infernal slander techniques, the myth of McCarthyism took flower” (p. 117). “By now,” says Coulter, “the left’s mind-boggling self-righteousness about Senator Joe McCarthy is so overwhelming, so hegemonic, it seems the record could never be set straight” (p. 75). To the contrary, Treason is a giant step toward setting it straight.

Of the so-called “War on Terror,” Coulter says: “You would think the most destructive terrorist attack in the history of the world would call for something new, but liberals have simply dusted off the old clichés from the Cold War and trotted them out for the war on terrorism” (p. 13). She chronicles the various reactions from the left on the “War on Terror,” from academia to Hollywood, including one celebrity who suggested that Americans putting fast-food chains in other countries contributed to 9/11.

Coulter does a good job along the way of identifying Islam as a key factor in the assault on America, pointing out that the left is ignoring this matter. “America was at war with Islamic fanatics, but liberals treated every new onslaught like a bolt out of the blue” (p. 282). Unfortunately, this identification remains true today, almost ten years after Coulter’s book was published.

Although much value is to be found in Coulter’s book, there is also much wrong with it. Coulter gives Reagan nearly exclusive credit for “vanquishing” communism (sharing it only with the American people’s faith in God), praises Republicans and conservatives as if they were almost perfect, and indicates that the Iraq war—in which thousands of Americans have lost their lives without any increase in American security—is vital and central to winning the “War on Terror.”

But Coulter gets worse when she considers more fundamental philosophical issues. Discussing conservative mystic Whittaker Chambers, Coulter writes:

It has been his fate he said, to have been “in turn a witness to each of the two great faiths of our time”—God and Communism. Communism, he said, is “the vision of man without God.” . . . These were the “irreconcilable opposites—God or Man, Soul or Mind, Freedom or Communism.” (pp. 8–9)

So, is Coulter conceding that communism is pro-man and pro-mind, while freedom is not? Coulter answers yes, saying, “Liberals chose Man. Conservatives chose God” (p. 9). Coulter credits Christian conservatism as being in defense of freedom, while blaming “aggressive secularism” as the source of the American left’s support of communists and Islamic terrorists (p. 288).

Later, Coulter again quotes Chambers: “The Western world does not know it,” Chambers said, “but it already possesses the answer” to Communism—having faith in God “as great as Communism’s faith in man” (p. 166). Applying Chambers’s thought, Coulter claims, “It wasn’t just military might or a preference for the materialist bounty of capitalism that drove Reagan’s victory over Communism. It was Americans choosing faith in God over faith in man” (p. 166). But why must Americans choose faith at all? Why choose between blindly serving communist overlords on the one hand and blindly serving an alleged God on the other? Why not choose a reason-based, rights-respecting society the likes of which the American Founders conceived? Coulter apparently does not consider this possibility.

Although Coulter does justice to Joe McCarthy and HUAC’s investigations and exposes how the American left disgracefully aided Soviet totalitarianism, her claim that communism—which she acknowledges is a “blood-soaked ideology”—is pro-man and pro-mind and can only be countered with religious mysticism is not only ridiculous; it is also a sign of extreme self-induced blindness. This goes to show how adherence to religion can utterly retard one’s most important thought processes—such as those about man’s nature, man’s means of knowledge, and the nature of good and evil—and how such adherence necessitates compartmentalization, the separation of ideas that, if permitted to interact, would scream: contradiction.

Contrary to Coulter, it is not “aggressive secularism” but mysticism in all its forms—including communism, Islam, and Christianity—that threatens civilization.

The net effect? As an informative critique of the American left, Treason is a worthwhile read. But look elsewhere for the fundamental positive ideas necessary to counter the forces of evil and to establish and maintain a civilized, rights-respecting society.

![[TEST] The Objective Standard](https://test.theobjectivestandard.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/logo.png)