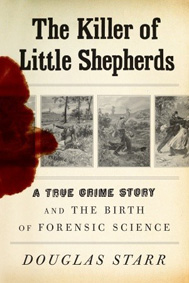

The Killer of Little Shepherds: A True Crime Story and the Birth of Forensic Science, by Douglas Starr. New York: Knopf, 2010. 320 pp. $26.95 (hardcover).

One day, in 1893, while taking a walk, nineteen-year-old Louise Barant met a slightly older man named Joseph Vacher (pronounced Vashay). After he asked about the weather, they went to a café, where, much to Louise’s surprise, Vacher proposed marriage. He added that if she ever betrayed him, he’d kill her.

In the following weeks, she tried to avoid him but to no avail. She told him that her mother forbade a relationship between them, but he persisted. Finally, she fled to the safety of another town. But Vacher soon showed up there and asked her once again to be his bride. When she refused, he pulled out a gun, shot her, and turned the gun on himself.

Because the person who sold Vacher the gun had loaded it with half charges, neither died from the bullet wounds, but the faces of both were disfigured. Vacher’s face was so disfigured that when he spoke it contorted into a disturbing grimace. In this condition, he was sent to an asylum far away from Louise.

In The Killer of Little Shepherds: A True Crime Story and the Birth of Forensic Science, Douglas Starr explains what happened in the years leading up to the shooting and what happened when, ten months later, the asylum’s guards opened the wrought-iron gates and set Vacher free.

Vacher’s ensuing rampage was one of the bloodiest of any serial killer in history. Newspapers would later describe his release as “opening the door to the cage of a wild beast” (p. 14). Starr shows that the analogy was apt.

However, as the book’s title indicates, Starr does not focus exclusively on Vacher. Instead, he oscillates between scenes of Vacher prowling the countryside and those of intelligent, methodical men solving crimes (Vacher’s and others) using the latest scientific techniques.

Starr focuses on one scientist in particular: Dr. Alexandre Lacassagne (pronounced Lackasanya), one of the most respected criminologists of his time. In all of France, writes Starr, “there could not have been two men more different than Joseph Vacher and Alexandre Lacassagne.”

Vacher was wild, rootless, primitive, ruled by impulses and sexual appetite. Lacassagne personified the bourgeois qualities of order, education, and dignity; he was regular in his habits, a voluminous reader, dedicated to service, restrained, and self-deferential. They were the opposite ends of the spectrum of human nature. . . . (p. 60)

Lacassagne may remind readers of the much-loved Sherlock Holmes. Indeed, as Starr relays, a comparison of the two appeared in an influential journal that Lacassagne started and that helped give rise to forensic science. The author of the comparison listed the values that the fictional and real-life detectives shared—“their appreciation for careful observation and the methodical compilation of evidence; their belief that each case should be approached with a logical plan; their appreciation for how even the tiniest bits of evidence could point to a solution; and their belief in the necessity of preserving an untrammeled crime scene” (p. 104) He also noted their differences. Whereas Lacassagne always acted in step with his advice to “avoid hasty theories and hold yourself back from flights of imagination” (p. 105), Holmes, who said something similar, would also make unwarranted deductions about the height of a suspect from the length of his stride or about the cause of a victim’s death without conducting an autopsy.

Starr brings Lacassagne into the story directly after Vacher is set loose from the asylum, and then proceeds to toggle back and forth between Vacher’s advance and the beginnings of forensic science, primarily the thinking and methods of Lacassagne. These jumps from one advancing line of events to another are both wonderful and excruciating, often because Starr transitions at the exact point you suspect that something big is about to happen.

At the end of one chapter, for example, Starr writes that Vacher “approached the farm of a man named Régis Bac and begged for some stew.”

He ate some and offered the rest to his dog. When the dog turned away, he said, “If you don’t want to eat it, I’ll kill you,” and smashed in her head with his club. Then he did the same to [his pet bird]. Bac said he was “horrified” by this brutality, and he gave Vacher a shovel so he could bury his animals. Vacher did so and left. His bloodlust was rising. (p. 146)

As he does in many similar instances, Starr leaves readers holding their breath at the end of this section by switching his focus to a different plotline, in this case to a magistrate searching for Vacher.

The magistrate, Emile Fourquet, had sent a bulletin to his peers across France describing Vacher and his crimes. Starr explains that Fourquet had just been disappointed by the discovery of someone who fit Vacher’s profile but wasn’t him, and was beginning to doubt that he’d ever catch the killer. And then,

Fourquet received a letter from the magistrate in Tournon, a town on the Rhone River, about fifty miles south of Lyon. A man was being held in the local jail on a charge of “outrage to public decency”—attempted rape. He seemed to fit the profile Fourquet had circulated. Fourquet asked his colleague to send a photo. The colleague replied that the town’s only photographer found the prisoner so menacing that he could not bring himself to aim a camera at his face. (p. 147)

Later in the book, Starr takes excursions from the ongoing action to present different turn-of-the-century opinions on what causes crime. One of Lacassagne’s contemporaries, for example, held that some men were predisposed to crime and that he could identify a criminal by the shape of his skull. Lacassagne found this view absurd. Was his own any better? Readers will have to decide for themselves.

By examining the people involved in this drama, Starr also raises the questions of what responsibility the insane have for their actions, and how juries might differentiate the truly mad from those feigning madness for a lighter sentence. Was Vacher insane? Should he have been returned to an asylum until he appeared to be “normal” again? Or was he cognizant of what he was doing and thus deserved to be put to death for his crimes? Such questions are a key part of the drama, as Lacassagne addresses them and presents his rationale in court.

Given its gruesome subject matter, The Killer of Little Shepherds is obviously not for everyone. But for those who can stomach villains as evil as they come in order to revere heroes as admirable, Starr’s book is highly recommended.

![[TEST] The Objective Standard](https://test.theobjectivestandard.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/logo.png)