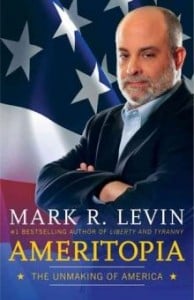

Ameritopia: The Unmaking of America, by Mark R. Levin. New York: Threshold Editions, 2012. 288 pp. $26.99 (hardcover).

The title of Mark Levin’s latest book, Ameritopia, is his term for “the grave reality of our day” (p. x), an America in transformation from a constitutional republic based on individual rights into a totalitarian state. The book is not a political manifesto. For that, Levin refers the reader to his previous book, “Liberty and Tyranny,” in which he warns about “the growing tyranny of government . . . which threatens our liberty, the character of our country, and our way of life” (p. ix).

In Ameritopia, Levin goes deeper, posing the question: “[W]hat is this ideology, this force, this authority that threatens us? . . . What kind of power both attracts a free people and destroys them?” (p. x) “The heart of the problem,” he argues, is “Utopianism . . . the ideological and doctrinal foundation [that] motivates and animates the tyranny of statism” (p. xi).

To make his case, Levin takes the reader on an illuminating and entertaining philosophical journey through history in layman’s terms.

In chapter 1 of part I, On Utopianism, Levin explains “The Tyranny of Utopianism” and contrasts it with its antipode, individualism and limited constitutional government. Some excerpts:

Tyranny, broadly defined, is the use of power to dehumanize the individual and delegitimize his nature. Political utopianism is tyranny disguised as a desirable, workable, and even paradisiacal governing ideology. There are, of course, unlimited utopian constructs, for the mind is capable of infinite fantasies. But there are common themes. The fantasies take the form of grand social plans or experiments, the impracticality and impossibility of which, in small ways and large, lead to the individual’s subjugation. (p. 3)

A heavenly society is said to be within reach if only the individual surrenders more of his liberty and being for the general good, meaning the good as prescribed by the state. (p. 5)

Clearly, utopianism is incompatible with constitutionalism. Utopianism requires power to be concentrated in a central authority with maximum latitude to transform and control. Oppositely, a constitution establishes parameters that define the form and the limits of government. (p. 17)

The [American] constitution reflects the Founders’ repudiation of utopianism and any notion of omnipotent and omniscient masterminds. (p. 18)

In chapters 2–5, Levin zeros in on the works of four philosophers he says “best describe the utopian mind-set and its application to modern-day utopian thinking and conduct in America. Plato’s Republic, Thomas More’s Utopia, Thomas Hobbes’s Leviathan, and Karl Marx’s Communist Manifesto are indispensable in understanding the nature of utopianism” (p. xi).

In part II, On Americanism, chapters 6–10 explore the writings of two thinkers Levin believes best exemplify the diametrically opposing view, John Locke and Charles de Montesquieu—including their respective influences on the Founding Fathers—and Alexis de Tocqueville for his “prescient insight” into “the unique character of the American people and their government” (p. xii).

In part III, On Utopianism and Americanism, Levin notes that the architects of America’s unmaking are too numerous to list” (p. 189), but two of the “most prominent” (p. 189) are Woodrow Wilson and Franklin D. Roosevelt, whose ideas and policies Levin relates to the thinkers discussed in part I. In chapter 11, he writes that these men were instrumental in transitioning America “from a society based on God-given inalienable individual rights protective of individual and community sovereignty to a centralized, administrative statism that has become a power unto itself” (p. 188). Levin notes Wilson’s ridicule of “the inalienable rights of the individual,” his repudiation of “the theory of checks and balances,” and his belief that “[g]overnments are living things and operated as organic wholes” requiring “living political constitutions [that] must be Darwinian in structure and in practice” (pp. 189–98). Wilson’s theories, Levin says, can be traced to the ideas presented in Plato’s Republic (p. 194) and Hobbes’s “great Leviathan” (pp. 192–93, 194, 197).

“A few decades later,” Levin writes, “Wilson’s post-constitutional utopianism would serve as a blueprint for Franklin Roosevelt” (p. 198). In particular, Levin focuses on Roosevelt’s “Second Bill of Rights,” which he describes as “not rights, [but] tyranny’s disguise.” “Roosevelt’s worldview,” Levin holds, “harks back to Thomas More’s Utopia, a precursor to Marx’s worker’s paradise” (pp. 203–4).

Under Barack Obama, Levin concludes, “The counterrevolution, which is over a century old, proceeds more thoroughly and aggressively today than before” (p. 207).

Opening chapter 12, “Ameritopia,” Levin writes: “The utopian mastermind seeks control over the individual. . . . His personal interests . . . are dismissed as selfish, unjust, and destructive. . . . Societal deconstruction and the transformation are not possible if tens of millions of individuals are free to live their lives and pursue their interests without constant torment, coercion, and if necessary, repression. In America, breaking with the past means breaking the individual’s spirit. . . . He must be reshaped to serve the greater good” (p. 209).

Levin argues, “Post-constitutional America bears the resemblance and qualities of a utopian enterprise. Its exact form and nature elude definitional precision, but its outlines are familiar enough. It shares ambitions, albeit inexactly, . . . with the hierarchical caste system in Plato’s Republic . . ., the artificial humanism of Thomas More’s Utopia, . . . the omnipresence of Thomas Hobbes’s Leviathan, . . . and the Marx-Engels class-based radical egalitarianism and its pursuit of the inevitable workers’ paradise” (pp. 212–13). To “prove the point . . . of the state of things” (p. 213), Levin cites numerous concrete examples of “utopian statism” in action, under the chapter subheadings Federal Taxing, Spending, and Debt (p. 214), Regulations and the Administrative State (p. 215), and “Entitlements” and the Administrative State (p. 225).

In the epilogue, Levin leaves no doubt where he believes America is and where it could be headed. “It is neither prudential nor virtuous to play down or dismiss the obvious—that America has already transformed into Ameritopia. The centralization and consolidation of power in a political class that insulates its agenda in entrenched experts and administrators, whose authority is also self-perpetuating, is apparent all around us and growing more formidable. The issue is whether the ongoing transformation can be restrained and reversed, or whether it will continue with increasing zeal, passing from a soft tyranny to something more oppressive” (p. 245). “So, my fellow countrymen,” Levin asks in closing, “which will it be— Ameritopia or America?” (p. 248)

Levin largely succeeds in his stated mission: to “identify, expose, and explain the character of the threat that America and, indeed, all republics confront” (pp. x–xi). He moves the reader to think philosophically and in a historical context, two perspectives that are sorely needed in today’s culture. And he quotes extensively from the thinkers he explores, placing their ideas side by side with each other’s and/or with his own analysis. His arguments are generally clear and easy to follow.

Even so, the book comes up short in substantial ways. For instance, Levin provides no objective foundation or definition of individual rights; he instead relies on the popular notion that they are “God-given” and that they mean roughly what everyone vaguely assumes them to mean. This is a glaring weakness, considering that the book’s focus is on the destruction of rights. Likewise, although he addresses the “power [that] both attracts a free people and destroys them” (p. x) and names the sources of these ideas, Levin seems perplexed as to why utopian statism takes root. In discussing “the magnificence of the American Founding” in the epilogue, he writes, “It seems unimaginable that a people so endowed by Providence, and the beneficiaries of such unparalleled human excellence, would choose or tolerate a course that ensures their own decline and enslavement . . .” (p. 242).

Ironically and tragically, it seems that liberty and the constitution established to preserve it are not only essential to the individual’s well-being and happiness, but also an opportunity for the devious to exploit them and connive against them. Man has yet to devise a lasting institutional answer to this puzzle. (p. 246)

Although Levin argues that “utopianism” is the “animating force” behind “statism,” he doesn’t attempt to identify the deeper philosophical premises that animate and explain utopianism’s hold on cultures. He acknowledges, at least implicitly, that utopianism depends on faith and altruism, and he condemns utopian statism as “a fantasy that evolves into a dogmatic cause, which, in turn, manifests a holy truth for a false religion” (p. 10). Under utopianism, he argues, the individual’s “first duty must be to the state—not to family, community, and faith”; therefore, he must “self-sacrifice for the utopian cause” (pp. 5–6).

But Levin misses the most crucial point: that faith and altruism, as such, are the fundamental culprits. His view amounts to: The utopians wrongly redirect faith and altruism from God, family, and community to the state. In this vein, he sprinkles the book with comments such as this, from Karl Popper, whom Levin quotes approvingly: “[I]ndividualism, united with altruism, has become the basis of Western Civilization. It is the central doctrine of Christianity” (p. 34). Levin does not make the connection that people’s acceptance of faith in and self-sacrifice to a higher power contradicts individualism and is the very thing that “the devious . . . exploit [to] connive against . . . liberty and the constitution established to preserve it” (p. 246).

Limited though it is in depth, however, Ameritopia provides an interesting survey of the ideas of some important thinkers whose ideas have shaped and are shaping our world.

![[TEST] The Objective Standard](https://test.theobjectivestandard.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/logo.png)