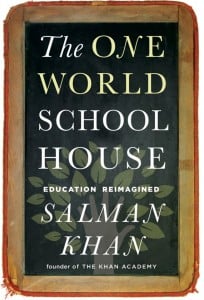

The One World Schoolhouse: Education Reimagined, by Salman Khan. New York: Twelve, 2012. 272 pp. $26.99 (hardcover).

In 2009, Salman Khan quit his job as a hedge fund analyst in order to devote time to Khan Academy—a grand name, explains Khan, for an entity with meager resources:

The Academy owned a PC, $20 worth of screen capture software, and an $80 pen tablet; graphs and equations were drawn—often shakily—with the help of a free program called Microsoft Paint. Beyond the videos, I had hacked together some quizzing software running on my $50-per-month web host. The faculty, engineering team, support staff, and administration consisted of exactly one person: me. The budget consisted of my savings. I spent most of my days in a $6 T-shirt and sweatpants, talking to a computer monitor and daring to dream big. (p. 5)

Khan’s dream was big. His mission was to “provide a free, world-class education for anyone, anywhere” (p. 5). And this, in part, is how he planned to provide it:

My basic philosophy of teaching was straightforward and deeply personal. I wanted to teach the way I wished that I myself had been taught. Which is to say, I hoped to convey the sheer joy of learning, the thrill of understanding things about the universe. I wanted to pass along to students not only the logic but the beauty of math and science. Furthermore, I wanted to do this in a way that would be equally helpful to kids studying a subject for the first time and for adults who wanted to refresh their knowledge; for students grappling with homework and for older people hoping to keep their minds active and supple.

What I didn’t want was the dreary process that sometimes went on in classrooms—rote memorization and plug-in formulas aimed at nothing more lasting or meaningful than a good grade on the next exam. Rather, I hoped to help students see the connections, the progression, between one lesson and the next: to hone their intuitions so that mere information, absorbed one concept at time, could develop into true mastery of a subject. In a word, I wanted to restore the excitement—the active participation in learning and the natural high that went with it—that conventional curricula sometimes seemed to bludgeon into submission. (p. 6)

At the start, Khan says, he worked with just one student, his cousin Nadia. However, his approach to education and his method of delivering it via videos became extremely popular in short order.

By the middle of 2012, Khan Academy . . . [was] helping to educate more than six million unique students per month—more than ten times the number of people who have gone to Harvard since its inception in 1636—and this number was growing by 400 percent per year. The videos had been viewed over 140 million times and students had done nearly half a billion exercises through our software. I had personally posted more than three thousand video lessons . . . covering everything from basic arithmetic to advanced calculus, from physics to finance to biology, from chemistry to the French Revolution. We were also aggressively hiring the best educators and software engineers in the world to help. The Academy had become the most used education platform on the Web, described by Forbes as “one of those why-didn’t-anyone-think-of-that stories . . . [Khan Academy] is rapidly becoming the most influential teaching organization on the planet.” (p. 8)

Anyone interested in learning more about this organization, its place in the history of education, and its plans for the future of education, should read The One World Schoolhouse: Education Reimagined.

Of the many things Khan shares therein, one is how he developed both the academy’s curriculum and its method of delivery. He recounts that, while asking his cousin questions over the phone and expecting answers straightaway, he noticed he was leading her to feel more uncomfortable and anxious about the subject they were studying, not less. This led him to create videos she could watch and, if necessary, watch again before tackling the separate issue of applying the knowledge gained to specific problems.

He explains that initially he kept the videos to roughly ten minutes because that was the limit set by YouTube, but, he continues, even after YouTube allowed longer videos he kept his around ten minutes because “educational theorists had long before determined that ten to eighteen minutes was about the limit of students’ attention spans” (p. 28).

Khan also says he chose a blackboard to appear in the background of his videos—and chose not to include his face in them—because he “wanted students to feel like they were sitting next to me at the kitchen table, elbow to elbow, working out problems together” (p. 34). And, there was another, related reason. As Khan puts it:

Human beings are hardwired to focus on faces. We are constantly scanning the facial expressions of those around us to get information about the emotional state of the room and our place in it. We seem to be hardwired to meet each other’s gazes, to read lips even as we are listening. Anyone who has ever raised a baby has noticed its particular attention while looking at its mother; indeed, its parents’ faces are probably the very first things a newborn manages to focus on.

So if faces are so important to human beings, why exclude them from videos? Because they are a powerful distraction from the concepts being discussed. What, after all, is more distracting than a pair of blinking human eyes, a nose that twitches, and a mouth that moves with every word? Put a face in the same frame as an equation, and the eye will bounce back and forth between the two. Concentration will wander. Haven’t we all had the experience of losing the thread of a conversation because we homed in on the features of the person we were talking with rather than paying steady attention to what was being said? (p. 34)

On the basis of such ideas, Khan developed his unique teaching videos. But, as readers of One World Schoolhouse will see, the education Khan Academy offers is unique in many other ways as well. One example is the difference between Khan’s approach to a passing grade and that of most educators today:

In most classrooms in most schools, students pass with 75 or 80 percent. This is customary. But if you think about it even for a moment, it’s unacceptable if not disastrous. Concepts build on one another. Algebra requires arithmetic. Trigonometry flows from geometry. Calculus and physics call for all of the above. A shaky understanding early on will lead to complete bewilderment later. And yet we blithely give out passing grades for test scores of 75 or 80. For many teachers, it may seem like a kindness or perhaps merely an administrative necessity to pass these marginal students. In effect, though, it is a disservice and a lie. We are telling students they’ve learned something that they really haven’t learned. We wish them well and nudge them ahead to the next, more difficult unit, for which they have not been properly prepared. We are setting them up to fail.

Forgive a glass-half-empty sort of viewpoint, but a mark of 75 percent means you are missing fully one-quarter of what you need to know (and that is assuming a rigorous assessment). Would you set out on a long journey in a car that had three tires? For that matter, would you try to build your dream house on 75 or 80 percent of a foundation?

It’s easy to rail against passing students whose test scores are marginal. But I would press the argument further and say that even a test score of 95 should not be regarded as good enough, as it will inevitably lead to difficulties later on.

Consider: A test score of 95 almost always earns an A, but it also means that 5 percent of some important concept has not been grasped. So when the student moves on to the next concept in the chain, she’s already working with a 5 percent deficit. Even worse, many deficiencies have been masked by tests that have been dumbed down to the point that students can get 100 percent without any real understanding of the underlying concept (they require only formula memorization and pattern matching).

Continuing our progression through another half dozen concepts—which might bring our hypothetical student to, say, Algebra II or Pre-Calc. She’s been a “good” math student all along, but all of a sudden, no matter how much she studies and how good her teacher is, she has trouble comprehending what is happening in class.

How is this possible? She’s gotten A’s. She’s been in the top quintile of her class. And yet her preparation lets her down. Why? The answer is that our student is a victim of Swiss cheese learning. Though it seems solid from the outside, her education is full of holes. (pp. 83–85)

In stark contrast to that traditional approach to grading, Khan Academy’s approach begins by “breaking the subject down into manageable but clearly interconnected chunks” (p. 172). It then requires students to prove they have mastered each one of those chunks before progressing on to the next. And Khan regularly reintroduces chunks learned previously in later videos and practice problems. Further, Khan continually concretizes the importance of those chunks by showing their real-world applications, and constantly integrates new knowledge with existing knowledge by showing the connections.

The academy’s approach also gives the students all the time they need to learn each concept or string of them. In fact, according to Khan, not doing this is one of the key failures of the current educational model, a failure that, in his view, nothing, not even smaller class sizes, can correct: “[W]hether there are ten or twenty or fifty kids in a class, there will be disparities in their grasp of a topic any given time. Even a one-to-one ratio is not ideal if the teacher feels forced to march the student along at a state-mandated pace, regardless of how well the concepts are understood” (p. 19).

In Khan’s view, then, the standard approach needs to be completely reversed. “In a traditional academic model,” he says, “the time allotted to learning a subject is fixed while the comprehension of the concept is variable. . . . What should be fixed is a high level of comprehension and what should be variable is the amount of time students have to understand a concept” (p. 39).

As promised in the subtitle of this book, Khan really does reimagine education. One World Schoolhouse is full of such profound ideas, showing where the current approach to education is wrong, why it is wrong, and what Khan recommends as the proper approach.

In presenting his own thoughts on the proper approach, however, Khan routinely cautions against possible misconceptions of his method. For example, continuing from an earlier excerpt in this review, here is what he says after explaining why he chose to keep his face out of the videos:

This is not to say that faces—both the teacher’s and the student’s—are unimportant to the teaching process. On the contrary, face time shared by teachers and students is one of the things that humanizes the classroom experience, that lets both teachers and students shine in their uniqueness. Through facial expressions, teachers convey empathy, approval, and all the many nuances of concern. Students, in turn, reveal their stresses and uncertainties, as well as their pleasure when a concept finally becomes clear.

But for all that, the face time can and should be a separate thing from first exposure to concepts. And these two aspects of the educational experience, far from being in conflict, should complement one another. The computer-based lessons free up valuable class time that would otherwise be spent on broadcast lectures—a model in which the students generally sit blankly with no effective way for teachers to appraise who’s “getting it” and who is not. By contrast, if the students have done the lessons before the interaction, then there’s actually something to talk about. There are opportunities for interchange. This last point needs to be emphasized, because some people fear that computer-based instruction is about replacing teachers or lowering the level of skill necessary to be a teacher. The exact opposite is true. Teachers become more important once students have initial exposure to a concept online (either through videos or exercises). Teachers can then carve out face time with individual students who are struggling; they can move away from rote lecturing and into the higher tasks of mentoring, inspiring, and providing perspective.

This suggests something that is at the heart of my belief system: that when it comes to education, technology is not to be feared, but embraced; used wisely and sensitively, computer-based lessons actually allow a teacher to do more teaching, and the classroom to become a workshop for mutual helping, rather than passive sitting. (p. 35)

For elaboration on how these elements can be integrated in a world-class way for anyone, anywhere, and on the value of a detailed record of one’s learning process, I highly recommend the book—especially if you are a parent. In addition to learning more about the foregoing issues and getting to know the man you might want to have teach your child math and science (and who, in any case, will be changing the educational opportunities available to kids everywhere), you will find a trove of ideas to improve the way you think about, seek, or engage in education.

Consider, for example, this passage on an ancient dichotomy concerning higher education:

[O]ur universities are still wrestling with an ancient but false dichotomy between the abstract and the practical, between wisdom and skill. Why should it prove so difficult to design a school that teaches skill and wisdom, or even better, wisdom through skill? That’s the challenge and opportunity we face today. (p. 69)

Or consider this passage on Khan’s view of the fundamental nature of learning:

I see it as an extremely active, even athletic process. Teachers can convey information. They can assist and they can inspire—and these are important and beautiful things. At the end of the day, however, the fact is that we educate ourselves. We learn, first of all, by deciding to learn, by committing to learning. This commitment allows, in turn, for concentration. Concentration pertains not only to the immediate task at hand but to all the many associations that surround it. All of these processes are active and deeply personal; all involve the acceptance of responsibility. Education doesn’t happen out in the ether, and it doesn’t happen in the empty space between the teacher’s lips and the student’s ears; it happens in the individual brains of each of us. (p. 45)

Although One World Schoolhouse is generally excellent in terms of both theory and practice, it does contain a few significant flaws. I’ll mention just the most egregious, which stems from Khan’s acceptance of egalitarianism.

Khan opposes homework, a position for which there may be legitimate arguments, but part of his case against it is that it gives some students an advantage over others—or, as he puts it, homework is a “driver of inequality” that “runs directly counter to both the stated aims of public education and to our sense of fairness” (p. 114). Suffice it to say, it is simply bizarre for a man who recognizes the need of a child’s mind to expand at its own pace and absorb as much knowledge as possible to simultaneously hold that a child should not be given homework because that might enable him to excel faster than others. Such is the power of philosophic ideas, whether right or wrong. Fortunately, neither this flaw nor the others affects the main value of One World Schoolhouse.

Khan has been given many accolades since he started making videos in his closet. And he deserves each one. He has reimagined education, and his ideas on the subject are and will continue changing the field for the better. Anyone involved in or even interested in education—whether a teacher or administrator or parent or (adult) student—will profit from reading this book.

![[TEST] The Objective Standard](https://test.theobjectivestandard.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/logo.png)