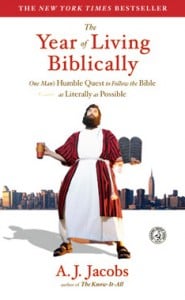

The Year of Living Biblically: One Man's Humble Quest to Follow the Bible as Literally as Possible, by A. J. Jacobs. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2007. 416 pp. $16 (paperback).

One way to determine the practical significance of ideas is to try practicing them. In The Year of Living Biblically: One Man’s Humble Quest to Follow the Bible as Literally as Possible, A. J. Jacobs sets out to do just that. What does “taking the Bible literally” mean? Jacobs explains:

To follow the Bible literally—at face value, at its word, according to its plain meaning—isn’t just a daunting proposition. It’s a dangerous one.

Consider: In the third century, the scholar Origen is said to have interpreted literally Matthew 19:12—“There are eunuchs who have made themselves eunuchs for the sake of the kingdom of heaven”—and castrated himself. Origen later became a preeminent theologian of his age—and an advocate of figurative interpretation.

Another example: In the mid-1800s, when anesthesia was first introduced for women in labor, there was an uproar. Many felt it violated God’s pronouncement in Genesis 3:16: “I will greatly multiply your pain in childbearing; in pain you shall bring forth children.” If Julie and I ever have another child, would I dare get between her and an epidural needle? Not a chance.

It’s a good bet that, at some time or other in history, every single passage in the Bible has been taken as literal. I’ve decided I can’t do that. That’d be misleading, unnecessary flip, and would result in missing body parts. No, instead my plan is this: I will try to find the original intent of the biblical rule or teaching and follow that to the letter. If the passage is unquestionably figurative—and I’m going to say the eunuch one is—then I won’t obey it literally. But if there’s any doubt whatsoever—and most often there is—I will err on the side of being literal. When it says don’t tell lies, I’ll try not to tell lies. When it says to stone blasphemers, I’ll pick up rocks. (p. 9)

At the start of Living Biblically, Jacobs describes himself as officially Jewish, but “Jewish in the same way the Olive Garden is an Italian restaurant. Which is to say: not very” (p. 3). Later he describes himself more accurately as agnostic, which is significant with respect to the progression of his quest. As he tells it:

In college I studied all the traditional arguments for the existence of God: the design argument (just as a watch must have a watchmaker so the universe must have a God), the first-cause argument (everything has a cause; God is the cause of the universe). Many were dazzling and brilliant, but in the end, none of them swayed me.

Nor did a line of reasoning I heard from my cousin Levi a couple of weeks ago. Levi—the son-in-law of my Orthodox aunt Kate—told me he believes in God for this reason: The Bible is so strange, so utterly bizarre, no human brain could have come up with it.

I like Levi’s argument. It’s original and unsanctimonious. And I agree that the Bible can be strange—the command to break a cow’s neck at the site of an unsolved murder comes to mind (Deuteronomy 21:4). Still, I wasn’t convinced. Humans have come up with astonishingly bizarre stuff ourselves: biathlons, turducken, and my son’s Chicken Dance Elmo, to name a few.

In short, I don’t think I can be debated into believing in God. Which presents a problem, because the Bible commands you not only to believe in God but to love Him. It commands this over and over again. So how do I follow that? Can I turn on belief as if it flows out of a spiritual spigot?

Here’s my plan: In college I also learned about the theory of cognitive dissonance. This says, in part, if you behave in a certain way, your beliefs will eventually change to conform to your behavior. So that’s what I’m trying to do. If I act like I’m faithful and God loving for several months, then maybe I’ll become faithful and God loving. If I pray every day, then maybe I’ll start to believe in the Being to whom I’m praying. (pp. 20–21)

The combination of his secular outlook and his willingness to assume the position of a believer enables Jacobs to view the Bible’s dictates without prejudice, to do as they command, and to see what happens.

As you might expect, a lot happens.

On day one, Jacobs begins growing a beard and obsesses over the Bible’s more than seven hundred rules “like a student driver who spends every moment checking the blinkers and speedometer, too nervous to contemplate the scenery” (p. 17). As the beard grows and the days pass, Jacobs limits the number of rules he focuses on at any given time to a manageable few, such as “the ban on wearing clothes made of mixed fibers” (p. 22) and the order to “blow the trumpet at the new moon” (p. 46).

Jacobs searches for and sometimes finds value in following certain rules, but he also finds himself utterly baffled at times:

How can these ethically advanced rules and these bizarre decrees be found in the same book? And not just the same book. Sometimes the same page. The prohibition against mixing wool and linen comes right after the command to love your neighbor. It’s not like the Bible has a section called “And Now for Some Crazy Laws.” They’re all jumbled up like a chopped salad. (p. 44)

Jacobs struggles to understand and to reconcile the different rules, but he repeatedly runs into dilemmas. For example:

I’ve been trying to love my neighbor, but in New York, this is particularly difficult. It’s an aloof city. I don’t even know my neighbor’s names, much less love them. I know them only as woman-whose-cooking-smells-nasty and guy-who-gets-Barron’s-delivered-each-week, and so forth. (p. 115)

Jacobs finds obstacles to his quest within his own family as well. His wife is not thrilled about the prohibition against touching her for the week after her period begins—“It’s like cooties from seventh grade,” she says, “theological cooties” (p. 50). His mother hates his new habit of adding “God willing” to the end of sentences in the future tense. She says he sounds like someone “who sends in videos to Al Jazeera” (p. 237).

Living Biblically is more than a record of one man’s efforts, confusions, and angst. It’s also a travelogue of sorts. Jacobs meets many odd and sometimes interesting people—from a preacher who handles snakes in Appalachia, to hundreds of dancing Hasidic Jews, to an Amish farmer who talks “slowly and carefully, like he only has a few dozen sentences allotted for the weekend, and he doesn’t want to waste them at the start” (p. 31).

As his quest progresses, Jacobs documents his changing views about the Bible, its rules, and his attempt to follow them. At times, it seems as though the cognitive dissonance strategy is working. Jacobs speaks as though God really does exist, for example, and he is quick to credit the biblical ledger for any benefits that result from his own actions. Even so, in his many efforts to blend biblical dictates with daily living, the ledger is difficult to keep orderly:

Today, before tasting my lunch of hummus and pita bread, I stand up from my seat at the kitchen table, close my eyes, and say in a hushed tone:

“I’d like to thank God for the land he provided so that this food might be grown.”

Technically, that’s enough. That fulfills the Bible’s commandment. But while in thanksgiving mode, I decided to spread the gratitude around:

“I’d like to thank the farmer who grew the chickpeas for this hummus. And the workers who picked the chickpeas. And the truckers who drove them to the store. And the old Italian lady who sold the hummus to me at Zingone’s deli and told me ‘Lots of love.’ Thank you.”

Here’s the thing: I’m still having trouble conceptualizing an infinite being, so I’m working on the questionable theory that a large quantity is at least closer to infinity. Hence the over-abundance of thank-yous. Sometimes I’ll get on a roll, thanking people for a couple minutes straight—the people who designed the packaging, and the guys who loaded the cartons onto the conveyer belt. Julie has usually started in on her food by this point.

The prayers are helpful. They remind me that the food didn’t spontaneously generate in my fridge. They make me feel more connected, more grateful, more grounded, more aware of my place in this complicated hummus cycle. They remind me to taste the hummus instead of shoveling it into my maw like it’s a nutrition pill. And they remind me that I’m lucky to have food it all. (pp. 94–95)

By the end of the quest, although he remains an agnostic, Jacobs says he is a reverent one.

I now believe that whether or not there’s a God, there is such a thing as sacredness. Life is sacred. The Sabbath can be a sacred day. Prayer can be a sacred ritual. There is something transcendent, beyond the everyday. It’s possible that humans created this sacredness ourselves, but that doesn’t take away from its power or importance. (p. 329)

The book is fun and full of laughs, but it is occasionally too forgiving of religion. For instance, as an agnostic, Jacobs holds that the existence of a supernatural being makes “just as much sense” as the absence of one (p. 248). This is false and unfair to religion. To make sense means that an idea is supported by sensory data. But there is no sensory evidence in support of the existence of a god, which is why religion demands faith, which is precisely acceptance of ideas in the absence of sensory evidence to support them.

Given the nature and aim of Living Biblically, however, this and similar flaws do not detract much from the book. As a guide to the Bible, its many dictates, and one man’s quest to follow them for a year, it is unrivaled.

![[TEST] The Objective Standard](https://test.theobjectivestandard.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/logo.png)