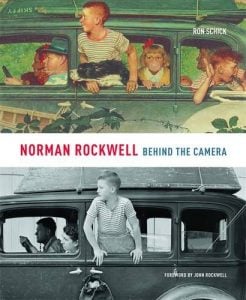

Norman Rockwell: Behind the Camera, by Ron Schick. New York: Little, Brown, and Company, 2009. 224 pp. $40 (hardcover).

People in paintings often do very little. Sometimes they are seated, looking blankly off into space, or asleep on a couch, dreaming who knows what. Their emotional expressions typically range from bored to unconscious. And they evoke little more than a yawn.

Contrast such subjects with those in the work of Norman Rockwell. The people in his paintings do quite a lot. The young boys and girls are visibly curious and sometimes even rowdy. They dunk each other in pools, gaze intently at lovers on a train, make faces in a mirror while getting a haircut. Their older siblings and parents are active as well. They race steamboats, compete in horseshoe forging contests, stand tall and speak their minds. Even the old men in Rockwell’s paintings are active, carrying frames through museums, swimming in rivers, playing music together after hours in a barbershop.

The emotional expressions of Rockwell’s subjects are equally unusual when compared to works of other artists. They exhibit intense concentration, open admiration, exaggerated silliness, solemn reverence, impassioned rage, disillusioned surprise, undiluted happiness. And when we view his paintings, we react accordingly.

In Norman Rockwell: Behind the Camera, author Ron Schick explores a major aspect of the method behind Rockwell’s art: his use of the camera. And the book stars many of the photos Rockwell took as references for his paintings, often side by side with the paintings themselves.

In Norman Rockwell: Behind the Camera, author Ron Schick explores a major aspect of the method behind Rockwell’s art: his use of the camera. And the book stars many of the photos Rockwell took as references for his paintings, often side by side with the paintings themselves.

Schick frames the pictures and paintings with insightful commentary. He observes, for example, that the camera enabled Rockwell to capture and later paint fleeting emotional expressions; gave him greater control over which colors he chose for the final painting; “freed him to depict his scenarios from above or below, up close or at a distance”; and enabled him to use characters who fit the idea he had in mind for a painting rather than try to “cast characters against type in roles they did not fit” (19, 20).

Schick also conveys some of the stories behind the pictures. Most have to do with the models and how Rockwell got them to express what he wanted them to express. Others have to do with the objects he wanted in the pictures. Consider this one, for example, about the kind of car Rockwell wanted for a picture and how he got it:

Rockwell photographed a variety of automobiles, but the one he wanted [for Going and Coming] was driven by his postman on his rounds. One day he met the postman at the mailbox and told him to go up to the house where something was waiting for him. There the postman found a check for twenty-five dollars for the use of his car, and when he returned, the car was gone. Rockwell had taken it to be photographed. (87)

Behind the Camera is peppered with such delights.

Mostly, though, Schick shows how Rockwell used the camera. Among other things, readers learn that Rockwell considered “the story” to be “the first thing and the last thing” and thought that “nothing should ever be shown in a picture which does not contribute directly to telling the story the picture is intended to tell” (9, 23). In accordance with that standard, Rockwell “envisioned his narratives down to the smallest detail,” “staged his photographs like a film director,” and “required [the photos] to portray his ideas exactly” (15, 16). Only then did he begin the respective paintings.

However, because Rockwell considered the story to be supremely important, he painted to tell his story, not to reproduce the photos. Consequently, the photos and his paintings are different in many ways. As Rockwell himself said, “Often I will enlarge an eye, reduce the size of the mouth, or do any number of things to make the character funnier or sadder or to portray any other expression needed to put over the story” (30).

Observant readers will spot such changes. Indeed, identifying the changes and noting the reasons for them is the chief value of Schick’s book, and readers who examine the photos and paintings with this in mind will come away with a deeper appreciation for Rockwell’s art—and, what’s more, a deeper understanding of how painters in general re-create scenes according to their own views of what is important.

On those grounds, I recommend Norman Rockwell: Behind the Camera not only for Rockwell fans, but for anyone interested in art.

![[TEST] The Objective Standard](https://test.theobjectivestandard.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/logo.png)