The Cave and the Light: Plato Versus Aristotle, and the Struggle for the Soul of Western Civilization, by Arthur Herman. New York: Random House, 2013. 704 pp. $13.99 (Kindle).

Arthur Herman’s The Cave and the Light is more than a history; it is an enlightening drama. It is not a novel, but it often reads like one. As Herman puts it, “This is neither a history of philosophy nor a history of Western civilization. It is an account of the interaction of both, and of how the legacies of Plato and Aristotle live on around us and continue to shape our world” (loc. 51).

Herman has not merely summarized dense treatises. He has brought their authors and those who have carried on their ideas to life. I disagree strongly with some aspects of Herman’s analysis, yet I found the book (particularly the Audible version) thrilling and educational.

The subtitle of the book is Plato Versus Aristotle, and the Struggle for the Soul of Western Civilization. “This book,” Herman says, “tells the story of how everything we say, do, and see has been shaped in one way or another by two classical Greek thinkers, Plato and Aristotle. . . . And at the center of their influence has been a two-thousand-year struggle for the soul of Western Civilization, which today extends to all civilizations” (loc. 25). It is refreshing to read a work that recognizes and conveys the role of fundamental philosophical ideas in shaping history, particularly amid the chorus of modern philosophers who treat the subject as though it were a game of words.

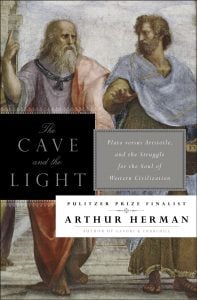

The greatest virtue of this book, and what makes it particularly enjoyable, is that Herman spares no effort in painting a rich, detailed, and imaginative picture of his subjects. And although the main subjects of the book are Plato and Aristotle, they are not the only subjects. Here, for instance, is how Herman indicates the genesis of Raphael’s painting The School of Athens, which adorns the book’s cover. After providing relevant historical context regarding Pope Julius II’s reign, Herman writes:

The greatest virtue of this book, and what makes it particularly enjoyable, is that Herman spares no effort in painting a rich, detailed, and imaginative picture of his subjects. And although the main subjects of the book are Plato and Aristotle, they are not the only subjects. Here, for instance, is how Herman indicates the genesis of Raphael’s painting The School of Athens, which adorns the book’s cover. After providing relevant historical context regarding Pope Julius II’s reign, Herman writes:

So at some point in the winter of 1508, he [the pope] and Raphael and Bramante would have wandered inside, passing teams of artists and assistants laboring in the halls with paintbrushes and trowels. They would have seen their breath as they stood in the frigid air. Their words would have echoed in that soaring empty space. “This shall be our personal library,” Julius probably said, gesturing toward the empty walls. “Give us a design suited to that purpose.” (loc. 123)

Herman acknowledges that we cannot know exactly what happened or what was said. But he artfully combines knowledge and imagination to fill in the gaps and bring the story to life.

The book is as heavy on facts and analysis as it is on fantasy and imagination. Herman offers incisive analysis of Plato’s and Aristotle’s works and ideas (as well as those of some major successors). For instance, he delves into the Timaeus, Plato’s creation myth, where we learn about how an immaterial god created the universe by using numerically modeled perfect Forms to shape an imperfect material world and all its objects. According to Plato, the abstract and immaterial creates the concrete and material; the “Forms,” as he calls the former, are primary and thus more important than the latter.

Herman later details how the early Christians usurped huge swaths of the Timaeus and wove it into their religion. “Today, historians point to social and economic factors to explain Christianity’s amazing spread. But the key factor was its skill in seizing the high ground of Greek thought, especially Plato” (loc. 2861).

On the other hand, writes Herman,

Aristotle decided that reality with a capital R [a reference to Plato’s World of Forms] is not (for the most part) something ultimately above or behind the world we see and hear and smell and touch. It is that world. What Plato had dismissed as the illusions of the cave [a reference to an allegory in which Plato depicts the world we experience as mere shadows of the Forms], Aristotle set out to prove were the keys to ultimate understanding all along. (loc. 967)

And Herman’s analysis is not limited to theory; he also shows what these ideas lead to in practice. For instance, he shows how and why Aristotle is the root of America, of capitalism, of technology, and ultimately, of optimism.

For an indication of the breadth of Herman’s analysis regarding the practical implications of Aristotle’s and Plato’s ideas, consider this passage in which he indicates the irony in Stalin’s recognition of the fact that American production was responsible for outfitting his Red Army in the Second World War:

“To American production, without which this war would have been lost”: that was the ceremonial toast of communism's biggest dictator, Marshal Josef Stalin, at the Tehran summit in 1943. He knew American industry had kept his Red Army on the move with trucks, half-tracks, and fuel, and his people clothed and fed throughout the war—providing almost one-fifth of Soviet GNP. It was also the acknowledgment by Platonism’s most potent political offspring—Marxist communism—that economies and societies built around Aristotle’s empirical system were not only wealthier and more productive but better able to meet the stress of crisis. (loc. 10320)

Herman also tells the story of Ayn Rand, who escaped Communist Russia when she was twenty and came to the United States.

“Everything that makes us civilized beings,” she wrote, “every rational value that we possess—including the birth of science, the industrial revolution, the creation of America, even the [logical] structure of our language, is the result of Aristotle’s influence.” (loc. 10357)

For all of his apt analysis, Herman does get some important things wrong. In particular, although his account of Aristotle’s influence is at times spot on, it is at other times way off. For instance, having observed the following:

Plato’s philosophy looks constantly backward, to what we were, or what we’ve lost, or to an original of which we are the pale imitation or copy. . . . Aristotle, by contrast, looks steadily forward, to what we can be rather than what we were. His outlook is by its nature optimistic: “The universe and everything in it is developing towards something continually better than what came before,” including ourselves. . . . In that sense, Aristotle is the first great advocate of progress—and Plato, creator of the vanished utopia Atlantis, the first great theorist of the idea of decline. (loc. 1105)

—Herman later writes that the reason the golden age of Islam came crashing to a halt was too much Aristotle and not enough Plato:

In short, “what went wrong” with Muslim culture, then and later, was that it wound up getting too much Aristotle too soon, which deprived it of growth and dynamism. Aristotle’s scientific and logical treatises became the basis of a fossilized orthodoxy in Arab culture, dry and lifeless and unchanging over the centuries. . . . Aristotle’s more humanistic works like the Politics and Nicomachean Ethics dropped from sight in the Islamic world, since the debate with Plato, of which they were an essential part, had been cut short. (loc. 10441)

Herman appears here to be conflating Aristotle’s ideas with the Muslim culture’s misunderstanding or misuse of Aristotle’s ideas. This and similar confusions lead Herman to underestimate not only the positive impact of Aristotle, but also the negative impact of Plato. And they lead him ultimately to a mistaken overarching evaluation of the two.

After identifying all manner of calamities caused by Plato’s influence—the gulags of Communist Russia, the concentration camps of Nazi Germany, and the like—Herman concludes, “Both [Plato and Aristotle] are indispensable to our culture and our future—and perhaps all futures” (loc. 10603). Perhaps Herman feels that he is being evenhanded in saying so. But the facts, history, and ideas of these two thinkers that Herman presents in The Cave and the Light do not warrant this evaluation.

Even so, Herman’s book provides a wealth of information and much food for thought. If you’re interested in why civilizations grow or stagnate, and the roles that Plato’s and Aristotle’s ideas have played in this regard, you’ll find substantial value in this book.

![[TEST] The Objective Standard](https://test.theobjectivestandard.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/logo.png)