Editor’s note: This essay originally was delivered as a presentation at TOS-Con 2019 and retains the quality of the oral presentation. Notes have been added to elaborate certain points and provide citations. To view a recording of this talk, click here.

I am going to begin with a question.

I assume that most everyone here consumes art, in some form, on a very regular basis. Each of us might do so more or less often, given our particular interests and the current state of our lives, and we might seek out art of greater or lesser complexity or sophistication, but we all seem to feel that fundamental and inescapable human need for the unique inspiration, relaxation, and rejuvenation that is given to us by art.

So, to fulfill that need, how many of you turn, at least a few times a month:

- To television?

- To movies?

- To novels?

- To great novels, by authors such as Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, and Hugo?

And how many of you turn, at least a few times a month, to classic poetry, by such authors as Tennyson, Keats, Wordsworth, and John Donne?

Not many. I am not surprised, and I don’t blame you in the least. I do blame your education, my education—these days, almost everyone’s education—for failing to make palpably and unforgettably real the distinct power of poetry to enrich our lives. I was fortunate enough to learn that power in spite of my education, and now I can no longer imagine my life without it.

I think the reason most people don’t consume poetry regularly is actually the very reason it is so fulfilling if you do: It is so dense with value that the value is not readily and immediately accessible. Allow me to illustrate.

For the next few moments, I am going to probably perplex, mystify, and bore you. Doesn’t that sound like a great start to a lecture? In other words, I am going to read you a great, classic poem cold.

It is called “On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer,” by John Keats.

Much have I travell’d in the realms of gold,

And many goodly states and kingdoms seen;

Round many western islands have I been

Which bards in fealty to Apollo hold.

Oft of one wide expanse had I been told

That deep-brow’d Homer ruled as his demesne;

Yet did I never breathe its pure serene

Till I heard Chapman speak out loud and bold:

Then felt I like some watcher of the skies

When a new planet swims into his ken;

Or like stout Cortez when with eagle eyes

He star’d at the Pacific—and all his men

Look’d at each other with a wild surmise—

Silent, upon a peak in Darien.

Do you feel enlightened, inspired, stirred deeply with emotion? Probably not. Nor did I the first time I read it. Almost without exception, when I encounter a great poem for the first time, it reads a little like flowery and archaic gibberish, and it leaves me emotionally flat. I think it is that experience that prompts many people to turn from poetry, believing it a barren source of amusement that aesthetes and snobby intellectuals make a pretense of enjoying.

But now I love “On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer” so much that it was torture for me to read it to you as I did just now, and I feel as if I committed a sacrilege. I hope Keats, who surely has rolled over in his grave, will forgive me for it in light of my larger purpose.

It is the richness of the language, the subtlety of the imagery, the musical form of the words in poetry that make it difficult to access upon first reading it and richly rewarding once you do. What I want to do now is demonstrate how to unlock a poem’s power. If I do it right, you will both learn to love this poem as I do, and, more important, learn a method for accessing the rich treasure of countless other such poems. So let’s dive in.

After you have chosen a poem to take on, the first task is simply to get out your dictionary and start looking up unfamiliar words. When I say unfamiliar words, I mean (1) any words you don’t know well enough to be able to articulate a clear definition for and (2) any words you think you know but suspect might admit of different meanings. I often am surprised to learn that a word I thought I knew well has a secondary definition that, once I know of it, brings the satisfaction of fitting a puzzle piece of the poem into place.

So what words might we need to look up here? Perhaps the following:

- Chapman: poet famous for his translations of Homer’s epics

- Homer: epic poet who wrote the Iliad and the Odyssey

- Goodly: pleasantly attractive

- Bard: a poet, usually one who recites epics

- Fealty: loyalty or devotion

- Demesne: land of an estate; property

- Serene: an expanse of clear sky or calm sea

- Ken: range of knowledge or sight

- Stout: brave and determined

- Cortez: Spanish explorer of the Americas (although “Chapman’s Homer” mistakes Cortez as the discoverer of the Pacific, it was instead Balboa)

- Surmise: supposition that something may be true

- Darien: a province in Panama

Once you feel confident that you know the meanings of all of the individual words, your next task is to try to translate the poem, line by line, into plain prose. Now, in doing so, we will be robbing the poem of almost all that gives it the distinct power of poetry, a distinction that I will elaborate on in a moment. But these “translations” are an important stage in the process of appreciating a poem for all it is worth.

So, let’s translate “Chapman’s Homer.”

If I were teaching this in my classes, we would spend a lot of time going back and forth, with you proposing translations and me helping to refine them. But because we have such a short time together, I have to shortcut that process and provide the translations for you.

Much have I travell’d in the realms of gold,

And many goodly states and kingdoms seen;

I translate this simply as, “I have traveled to many enchanting lands.” But does he mean that he has traveled to them literally, or in some metaphorical form? Here we have to integrate this with the lines that follow, which talk about the islands described by Greek poets and the experience of discovering them through Homer. So more precisely, I think Keats is saying, “I have traveled to many enchanting lands through poetry.” The poem continues:

Round many western islands have I been

Which bards in fealty to Apollo hold.

Here, he says that he specifically has explored “western islands” described by poets who wrote in tribute to the Greek god Apollo; in other words, he is saying, “I have read many versions of Ancient Greek epic poetry.” He then writes:

Oft of one wide expanse had I been told

That deep-brow’d Homer ruled as his demesne;

Keats had often been told that the great Greek epic adventures were best told by Homer—that these were his domain. Then we hear:

Yet did I never breathe its pure serene

Till I heard Chapman speak out loud and bold:

But Keats had never experienced the greatness of Homer for himself, never truly felt it, never breathed it, until he read the translation by the English dramatist George Chapman.

In this last section, “Then felt I like some watcher of the skies,” we have Keats’s reference to an astronomer and to Cortez.

For Keats, a poet who first discovered the beauty of Homer’s poetry thanks to Chapman, it was an experience so wondrous and so awe-inspiring that it felt akin to an astronomer discovering a new planet, or an explorer first sighting a previously undiscovered ocean.

These translations take work. In doing that work, it can be very helpful to simply Google the title of the poem and the word “analysis.” What you get will vary tremendously in accuracy and helpfulness, so you do have to sort the wheat from the chaff, but if you browse through the top listings, you inevitably will find some that help to clarify particular lines when you feel stuck.

You will also often discover short biographical anecdotes that provide context for the poem and contribute still another dimension to your enjoyment—anecdotes such as this one, about “On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer.”

John Keats lived a short life marred by tragedy. Both parents died when he was very young. He was left with no inheritance and struggled all his life with poverty. He fell madly in love but was unfit for marriage both because of his financial situation and because of the growing signs that he was suffering from tuberculosis, which he succumbed to at the age of twenty-five. Keats once said, “I have never known any unalloy’d Happiness for many days together: the death or sickness of some one has always spoilt my hours.”1

Much of the happiness he did know in his short life came from the time he spent with his beloved friend and tutor, Charles Cowden Clarke.

He and Cowden Clarke would spend evenings rhapsodizing together over poetry and talking into the early hours of the morning, reluctantly separating with a handshake at daybreak. On one of these occasions, Cowden Clarke was thrilled to have been loaned a copy of the Chapman translation of Homer. In his memoirs, he says that he and Keats spent a “wine-warmed evening” poring over passages and relishing their “muscular music.”

Chapman’s translation was a revelation to Keats, and it opened his eyes like nothing before to Homer’s “realms of gold.”

In the early hours of the morning, Keats walked home and sat down to write a sort of thank-you note to Cowden Clarke that would memorialize the thrill of that eye-opening experience. He had finished it, addressed it, and sent it to Cowden Clarke before ten that same morning. That “thank-you note” is this sonnet, which has been beloved for centuries.

When you do some quick research, sometimes you will discover gems such as that story, other times you won’t. But in this case, knowing the circumstances under which this poem was written made me love it all the more.

Once you have looked up words, written translations, searched for readily accessible context, and have a pretty good grasp of the poem’s basic meaning, it also can be useful to identify the theme, by which I mean, the basic feeling, or idea, or experience the poem seeks to convey.

In this case, it is ironic that initially I was so perplexed by the poem’s meaning, because I think its theme is that of revelation, of the discovery of a new horizon or of the dawning of a new appreciation. Ironic, because that is precisely what I felt once I thoroughly grasped the poem’s meaning, appreciated its beauty, and realized that this transformative experience was even possible. “Chapman’s Homer” is about revelation, and the experience of unlocking it was, for me, a revelation.

I now have this poem to offer me poignant phrases and evocative images for the experience of any sort of awakening. It can be useful to consider a moment in your life when you have experienced that sort of a revelation, when you have had a “Chapman’s Homer moment.” If I am lucky, you will have at least some reflection of that experience from this lecture, and I will have opened your eyes to the new horizon of great poetry.

Once you have done all this work to understand and appreciate the poem, you should read it again. Out loud. I will do that for you right now.

Much have I travell’d in the realms of gold,

And many goodly states and kingdoms seen;

Round many western islands have I been

Which bards in fealty to Apollo hold.

Oft of one wide expanse had I been told

That deep-brow’d Homer ruled as his demesne;

Yet did I never breathe its pure serene

Till I heard Chapman speak out loud and bold:

Then felt I like some watcher of the skies

When a new planet swims into his ken;

Or like stout Cortez when with eagle eyes

He star’d at the Pacific—and all his men

Look’d at each other with a wild surmise—

Silent, upon a peak in Darien.

I hope that experience was different from the first.

I mentioned earlier that our “translations” would rob the poem of its distinct value as poetry. I want to take a few moments to discuss what that value is before I move on to our next poem.

Imagine if the actual poem read like our translations:

I have traveled to many enchanting lands through poetry.

I have enjoyed many versions of the Greek epics.

I had often been told that the story of the Trojan War was best told by Homer.

Not quite the same, is it? That is because what is so captivating about great poetry is that it uses all the resources of language in harmony together to highlight, capture, and illuminate our most important life experiences. I am going to repeat that, because it is important. Great poetry uses all the resources of language in harmony together to highlight, capture, and illuminate our most important life experiences. The result is a deep insight made musical.

Poets employ words not just with regard for their literal meaning, but for their connotation, for their sound, for their flow and rhythm. As poet Alexander Pope put it simply, and poetically, “The sound must be an echo to the sense.” Poetry is palpable: It conveys its message through the use of evocative imagery and the distillation of an abstraction into a compelling, concrete, sensory reality. All that can be true of great prose writing, too, but to the extent it is, we call that writing poetic.

In “Chapman’s Homer,” for example, we have the sheer pleasure of hearing the flow of the words and the harmony of the rhymes. We have the literal and connotative meanings of phrases such as “breathe its pure serene,” which combines the archaic definition of “serene” (an expanse of clear sky or calm sea) with the suggested feeling of serenity that such a discovery brings. We have the images of revelation—an astronomer discovering a new planet or an explorer a new ocean—and the very sound of awe in the words: “Then felt I like some watcher of the skies.” And we have the moment of awed silence Keats creates with the rhythm of his words: “And all his men looked at each with a wild surmise, silent, upon a peak in Darien.” That simple punctuation—silent—and the forced pause that induces a moment of silence reinforce the spirit of reverence in the words.

We could spend all day deciphering what Keats has done to make these words so compellingly beautiful. But I want you to see how repeatable an experience this is and move on to our next poem.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti was an artist and cofounder, with William Holman Hunt and John Everett Millais, of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, a secret society of young artists who banded together against what they saw as the artificial and mannered approach to art then taught in London’s Royal Academy of Arts. The paintings of the Pre-Raphaelites were characterized by attention to minute detail, luminous colors, and ennobling themes. Some of their most notable works include Millais’s Ophelia, Waterhouse’s The Lady of Shallott, and Rossetti’s own Proserpine. All of these works, by the way, can be seen in a single glorious room in the Tate Britain in London, which, if it isn’t already, ought to be on your bucket list.

Rossetti was also a poet—and the author of a poem that took me completely by surprise and became an unlikely favorite of mine. It is called “The Woodspurge.”

I am going to start again by reading this poem to you cold.

The wind flapped loose, the wind was still,

Shaken out dead from tree and hill:

I had walked on at the wind’s will, —

I sat now, for the wind was still.

Between my knees my forehead was, —

My lips, drawn in, said not Alas!

My hair was over in the grass,

My naked ears heard the day pass.

My eyes, wide open, had the run

Of some ten weeds to fix upon;

Among those few, out of the sun,

The woodspurge flowered, three cups in one.

From perfect grief there need not be

Wisdom or even memory:

One thing then learnt remains to me, —

The woodspurge has a cup of three.

The first time I read this, not much “remained to me” at all.

I am going to assume that I have bored you yet again, but interestingly, the challenge with this poem is different. Here we have no archaic language, no unfamiliar words (except, perhaps, “woodspurge,” which is a flowering plant found in woodland areas in Europe). Nevertheless, because this, like all great poems, uses the rich resources of language and conveys a theme through evocative and indirect imagery, we still have to dwell in contemplation of it for a while before we can grasp its meaning entirely.

So, let’s still do a sort of translation, taking this line by line and considering the significance of each.

The wind flapped loose, the wind was still,

Shaken out dead from tree and hill:

Rossetti has set a countryside scene, with tree and hill, and said that there the wind is blowing in fits and starts, sometimes flapping, sometimes still. But describing the wind as “shaken out dead” sets a somber tone and evokes thoughts of death. In a poem called “The Wind” by Robert Louis Stevenson, he writes:

I saw you toss the kites on high

And blow the birds about the sky;

And all around I heard you pass,

Like ladies’ skirts across the grass—

That is a very different wind, suggestive of a very different mood.

Next:

I had walked on at the wind’s will, —

I sat now, for the wind was still.

He had walked at the wind’s will and sat because the wind was still. There is a passivity or inertia in his movements. The atmosphere is somber, and the narrator languid and listless.

Between my knees my forehead was, —

My lips, drawn in, said not Alas!

My hair was over in the grass,

My naked ears heard the day pass.

His lips are drawn in and silent. His head is hung between his knees so that his hair mingles with the grass. His ears are naked, uncovered, allowing him to take in the world that moves around him—but he is not taking it in, he is not engaged with it, and it passes him by. He does not say the word “Alas!,” but everything about his posture and passivity tells us that he has something terrible to lament.

My eyes, wide open, had the run

Of some ten weeds to fix upon;

Among those few, out of the sun,

The woodspurge flowered, three cups in one.

His eyes are blankly wide, but narrowly focused, seeing nothing but the weeds (note the dismal connotation again) that take up the whole of the limited sight allowed to him given his posture. And among them is a single flowering woodspurge.

This moment has been made so palpably real. You can picture this man idly walking at the wind’s will, sitting down in a stupor, and so numbed to the world around him that he is capable of noticing nothing but the weeds between his knees. But what is the point?

Rossetti tells us:

From perfect grief there need not be

Wisdom or even memory:

One thing then learnt remains to me, —

The woodspurge has a cup of three.

Here we have a more abstract statement: that this was a moment of grief, but that what he recalls is not the grief itself, nor any abstract, philosophic reflection on grief but, instead, an arbitrary, meaningless, simple, concrete observation—that the woodspurge forms three flowers. That thought was all he could manage.

We have in this poem an intensely powerful, concretized portrait of one aspect of grieving. Rossetti describes the feeling of being dazed, unfocused, numb, unconscious of the world that passes by in its normal course of activity. He was capable of no real thought and not even any distinct emotion and could do nothing more than passively note what was immediately before him. Rosetti offers not an abstract explanation of what it is to grieve, but a forceful image of it.

In this poem, Rossetti insightfully captured something universal in an experience that was also intensely personal. His wife, Lizzie, a poet, artist, and model for the pre-Raphaelites, was frail and ill when they married, likely from tuberculosis, soon after became pregnant, and gave birth to a stillborn child, and then died of an overdose of laudanum, possibly a suicide. One day, in a state of total despair, Rossetti idly picked up a book of natural history and came upon a picture of a woodspurge. According to a biographer, “He was tired and dejected; he could see, think of, nothing but the woodspurge engraved in the book on his knee. Out of this he made his poem—so sincere, profound, and terse that it affects its readers as an experience of their own.”2

With our definitions, translations, and context behind us, let’s read “The Woodspurge” once more. Imagine Rossetti, in his deep mourning:

The wind flapped loose, the wind was still,

Shaken out dead from tree and hill:

I had walked on at the wind’s will, —

I sat now, for the wind was still.

Between my knees my forehead was, —

My lips, drawn in, said not Alas!

My hair was over in the grass,

My naked ears heard the day pass.

My eyes, wide open, had the run

Of some ten weeds to fix upon;

Among those few, out of the sun,

The woodspurge flowered, three cups in one.

From perfect grief there need not be

Wisdom or even memory:

One thing then learnt remains to me, —

The woodspurge has a cup of three.

In her remarkable book Poetry: A Guide to Its Understanding and Enjoyment, Elizabeth Drew says, “The best religious poetry never preaches; it communicates what it feels like to have the poet’s faith.”3 Here, Rossetti does not preach to us about grief, but makes us feel, deeply and poignantly, what it means to grieve.

From this poem, I conceptualized the idea of a “woodspurge moment.”

The most unforgettable of such moments for me was the morning of 9/11. I was getting ready to start my day when I received a call from my friend Amy Peikoff asking, “Have you heard the news?” I said I hadn’t—and I can still hear the tone in her voice as she said, “Oh, Lisa.”

I was living in Southern California, and when I walked outside, it seemed so odd: The sun was still shining, the birds were still twittering, people were still passing by. But I felt stopped, locked in a despairing moment, separate from all that seemed to be happening outside of me and without me. Victor Hugo has his own poetic way of describing this sort of a sensation. In Ninety-Three, he says: “Nature is merciless; she never consents to withdraw her flowers, her music, her fragrances and her sunbeams before human abomination.”4

Also in Ninety-Three (which, if you haven’t read, you absolutely must), Hugo tells the story of Michelle Flechard, a mother separated from her children when she is shot and they are taken hostage as a bargaining tool in the French revolutionary war.

When she is discovered by the peasant Tellmarch, Michelle Flechard is on the brink of death. He takes her to his hovel and nurses her back to life, but when she revives, she is capable of uttering only three words: the names of her children.

Hugo writes,

She spent long hours at the foot of the old tree, in a state of stupefaction. She thought and said nothing. Silence offers a kind of shelter to simple souls that have undergone the sinister deepening of sorrow. She seemed to give up all effort to understand. There is a stage at which despair becomes unintelligible to the person who feels it.

She, too, was experiencing a woodspurge moment.

I am sorry for breaking your heart with contemplation of such moments (and a warning, there is more heartbreak to come), but there is a profound satisfaction in having someone articulate, insightfully and eloquently, what we might feel. The more of these experiences, and observations, and feelings that are so beautifully conceptualized for us—good and bad, joyful and tragic, inspirational and appalling—the richer and more substantive our lives become. Elizabeth Drew, again, puts it well when she says, “Poetry indeed is not ‘like life,’ but awakens and quickens new life. The poets find the right words in the right order for what we already dimly and dumbly feel, and they also fertilize in our consciousness responses which were lying inert and cloddish.”5

Poetry captures for us in a melodic and memorable form what it is to have a “Chapman’s Homer moment” or a “woodspurge moment,” and all the other experiences contained in the vast treasury of great poems. When we read them, we become people capable of a more penetrating vision, depth of thought, and intensity of feeling. Our lives are enriched.

Allow me to illustrate this point again, with another poem—sad, I’m sorry, but also so very beautiful: “Surprised by Joy,” by William Wordsworth.

Surprised by joy—impatient as the wind

I turned to share the transport—Oh! with whom

But Thee, deep buried in the silent tomb,

That spot which no vicissitude can find?

Love, faithful love, recalled thee to my mind—

But how could I forget thee? Through what power,

Even for the least division of an hour,

Have I been so beguiled as to be blind

To my most grievous loss?—That thought’s return

Was the worst pang that sorrow ever bore

Save one, one only, when I stood forlorn,

Knowing my heart’s best treasure was no more;

That neither present time, nor years unborn,

Could to my sight that heavenly face restore.

In a Wordsworth poem, there is likely to be some unfamiliar language. Let’s look at what we need to define here:

- Transport: overwhelmingly strong emotion

- Vicissitude: change or alteration, as between seasons

- Beguiled: charmed or enchanted

- Pang: sudden sharp or painful emotion

- Forlorn: pitifully sad, lonely, hopeless

Now, with these words solidly within our grasp, let’s work out a translation.

Surprised by joy—impatient as the wind

I turned to share the transport—

Suddenly overcome with a feeling of joy, our narrator turned impatiently to share in the feeling with someone loved. But the feeling of joy wasn’t just sudden; it was surprising. This is clearly someone for whom joy, at least of late, doesn’t often come.

The next lines tell us why.

Oh! with whom

But Thee, deep buried in the silent tomb,

That spot which no vicissitude can find?

The person with whom he wished to share his joy is dead, agonizingly unreachable, buried in a grave beneath the earth.

Love, faithful love, recalled thee to my mind—

But how could I forget thee? Through what power,

Even for the least division of an hour,

Have I been so beguiled as to be blind

To my most grievous loss?

It is love, he thinks, that called to mind the person with whom he wished to share his joy. But then he wonders, how could he, given that love, have ever even for a moment stopped thinking about her, when her death was the most devastating, most grievous thing ever to happen to him?

That thought’s return

Was the worst pang that sorrow ever bore

Save one, one only, when I stood forlorn,

Knowing my heart’s best treasure was no more

The devastation of remembering his loss, after feeling a fleeting moment of joy, is the worst pain he has ever suffered—with one exception: the day he suffered the loss itself, the day he learned that he would never again lay eyes on the “heavenly face” of his “heart’s best treasure.”

In my research of this poem, I happened upon a plain-language “translation” of it by an anonymous poetry enthusiast. Poetic in its own right, it helped to clarify for me the meaning of the poem in a description that retains something of the poem’s distinctive power. This is translation on another level, a kind that’s also worth trying yourself. Here it is:

Imagine you are a besotted father galled by the death of a beloved daughter. Imagine that all your delight in life and living was then forever depleted by the tragic loss; that every waking thought was only of her, and all your dreams damaged by a perpetual grief; that the only aspiration left in this life was the hope of an end to life. Now, imagine a moment, the briefest of moments when your dejection evanesces, when for some reason you forgot your daughter was dead and all the cause of your disconsolate grief was evaporated in a moment of elation and ineffable joy. You turn to the person you have always shared these moments of ecstasy with, for at last after long abeyance there is joy in your life once more. But the person isn’t there, for she is dead, how on earth could you forget? And your grief returns with a pang surpassed only by that first time you lost her forever. Even in the moment you forgot her, your thoughts were only of her: this is the nature of love.6

This poem is about grieving the death of a loved one. But rather than taking on this theme abstractly, Wordsworth gives his poem poignancy by capturing, with excruciating vividness, a moment of grieving: the experience of a transient feeling of joy, when you forget . . . and then the compounded pain of remembering.

Let me read the poem to you again.

Surprised by joy—impatient as the wind

I turned to share the transport—Oh! with whom

But Thee, deep buried in the silent tomb,

That spot which no vicissitude can find?

Love, faithful love, recalled thee to my mind—

But how could I forget thee? Through what power,

Even for the least division of an hour,

Have I been so beguiled as to be blind

To my most grievous loss?—That thought’s return

Was the worst pang that sorrow ever bore

Save one, one only, when I stood forlorn,

Knowing my heart’s best treasure was no more;

That neither present time, nor years unborn,

Could to my sight that heavenly face restore.

I have recommended that once you understand the poem, you connect it to other experiences. I want to share with you a connection that hit me like a ton of bricks. It was a moment I read about in the biography of Richard Feynman.

Feynman was a brilliant physicist and Nobel Prize winner famous for his discoveries in the field of quantum mechanics and his contributions to the Manhattan Project at Los Alamos. He has become a particular hero of mine because of his views on education. (I highly recommend the BBC special “The Pleasure of Finding Things Out”). I love him, too, because he appears to have been a great romantic.

Feynman’s wife, Arline, was diagnosed with a serious case of tuberculosis before they married. (Look at all the tragedy that has been eliminated by eliminating the threat of tuberculosis!) His parents opposed him marrying a sick girl, but he was resolute. He said, “I want to marry Arline because I love her—which means I want to take care of her. That is all there is to it. I want to take care of her.” Arline lived in a hospital in Albuquerque while Feynman worked on the Manhattan project, and he remained loyal, devoted, and attentive, making sure she was well cared for, visiting her most every weekend, and writing to her several times a week. She eventually succumbed to the disease.

Feynman, an avowed atheist, wrote a letter to Arline years after her death. It read:

D’Arline,

I adore you, sweetheart . . . It is such a terribly long time since I last wrote to you—almost two years but I know you’ll excuse me because you understand how I am, stubborn and realistic; and I thought there was no sense to writing. But now I know my darling wife that it is right to do what I have delayed in doing, and what I have done so much in the past. I want to tell you I love you.

I find it hard to understand in my mind what it means to love you after you are dead—but I still want to comfort and take care of you—and I want you to love me and care for me. I want to have problems to discuss with you—I want to do little projects with you. I never thought until just now that we can do that. What should we do. We started to learn to make clothes together—or learn Chinese—or getting a movie projector. Can’t I do something now? No. I am alone without you and you were the “idea-woman” and general instigator of all our wild adventures.

When you were sick you worried because you could not give me something that you wanted to and thought I needed. You needn’t have worried. Just as I told you then there was no real need because I loved you in so many ways so much. And now it is clearly even more true—you can give me nothing now yet I love you so that you stand in my way of loving anyone else—but I want you to stand there.

I’ll bet that you are surprised that I don’t even have a girlfriend after two years. But you can’t help it, darling, nor can I—I don’t understand it, for I have met many girls and very nice ones and I don’t want to remain alone—but in two or three meetings they all seem ashes. You only are left to me. You are real.

My darling wife, I do adore you. I love my wife. My wife is dead,

Rich.

PS Please excuse my not mailing this—but I don’t know your new address.7

He was, clearly, madly in love and thoroughly devastated by his loss. But when Arline died, Feynman was stoic. When friends at Los Alamos asked after her or tried to console him, he would say, “She’s dead. And how’s the program going?” In Feynman’s own recollection, recorded in the autobiographical What Do You Care What Other People Think?, he did not cry for a full month after her death.

Then, one day, he was walking by a boutique and saw a dress in the window and thought, “Arline would like that.” Then, only then, after the brief, fleeting feeling that she was still there—and the dreadful recollection that she was gone—did he break down in devastated tears. He succumbed to his grief only after having been surprised by joy.

Now, I am conscious that these last two poems have been very, very sad. But there is such enrichment, such joy, within the sadness. Notice that in the plain-language summary of “Surprised by Joy” that I quoted, the writer began by describing the enormity of the loss, and he concluded by saying, “This is the nature of love.” Tragedy has a corollary: Such a terrible loss can be felt only because there had been a deep love. Reading poems of great sadness helps us to feel understood in our own suffering and to give words to our grief. But also, this distilled experience of loss helps us to savor the presence of those we love. And, too, anything that makes us feel, deeply and meaningfully, stretches the very capacity of our souls.

That is why I love sad poems.

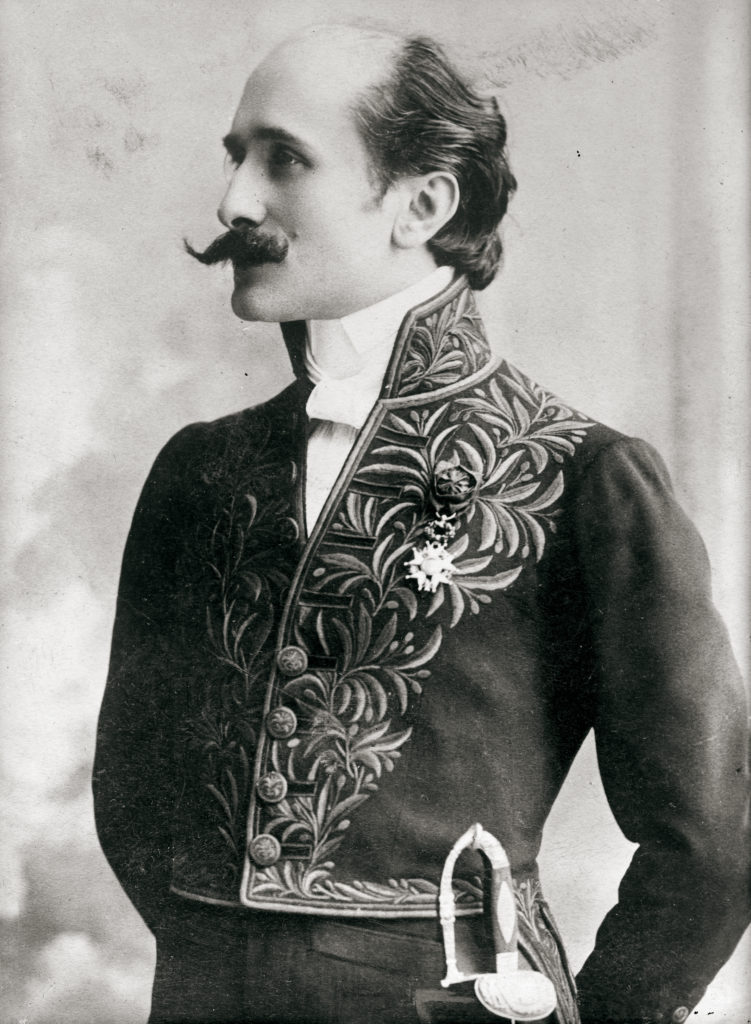

Nevertheless, as I was preparing this talk, I resolved that I should end on a happy note. So, I sincerely thought to myself, what is the very happiest thing I could possibly share? Pictures of my kids: but no, something more appropriate to our purpose. For me, there was an easy answer. Because right now, I am completely obsessed and madly in love with Edmond Rostand.

If you know that name, you probably recognize him as the creator of Cyrano de Bergerac, the swashbuckling poet with the heroic soul and the enormous nose. For those who don’t know it, I will repeat the story told many times before, that when Ayn Rand was asked what were her three favorite plays, she answered: Cyrano de Bergerac, Cyrano de Bergerac, and Cyrano de Bergerac. Let me just say a quick word about that play.

Cyrano is the story of a passionate and principled hero who makes no compromises in pursuit of the ideal. It earns him many enemies, but when he sees the supplicating way that others make friends, as, he says, a dog makes friends, he thinks to himself, “Thank god, there goes another enemy.” The play features an idealist and is written in a spirit of idealism: It is composed in exquisite verse, and it is uncompromising in its display of lyrical beauty.

It was written at the close of the 19th century, when French theater was increasingly dominated by cynicism and naturalism. Beauty was being forced out.

The contrast between Rostand’s bold idealism and the theatrical fashion of the day was never more evident than the night a celebration was held in honor of the great French actress Sarah Bernhardt. Rostand was asked to close the event, and he paid the actress tribute in a breathtaking sonnet. It read (but so much more beautiful, in rhyming French):

In this time without beauty, none but you knows

How to palely descend a spotlighted stair,

Brandish a sword, or brush back your hair—

Princess of the gesture, and queen of the pose!8

Participants in the event moved directly from this celebration to the debut of an important new theatrical production. They were startled—some appalled, some amused—at the opening line, which was “Merde!”9 (Which means: “Shit!”) Rostand biographer Sue Lloyd comments, “The 20th century had arrived.”10 (It sounds like a scene straight out of an Ayn Rand novel.)

Because Rostand regarded the world in which he lived as so alien to his own soul, he was terrified that his Cyrano de Bergerac would be a flop. Would modern audiences be receptive to Rostand’s old-fashioned devotion to uninhibited beauty?

Producers were also unsure, and Rostand had to pay most of the production costs himself. The night before the debut, he was found weeping in the dressing room of the play’s star, Benoit-Constant Coquelin. Rostand said, “Forgive me my friend, for having dragged you into this disastrous adventure.” But Coquelin replied, confidently, “There is nothing to forgive. You have given me a masterpiece.”11

As it turns out, opening night of Cyrano de Bergerac was one of the great historic moments of French theater. By the third act, ladies were throwing their gloves and men their opera hats on stage. The audience was invading the wings to congratulate Rostand and the actors. After the final act, the audience leaped as one to its feet and cheered—for hours. Literally. There were forty curtain calls. Men who were supposed to fight duels the next day embraced and called them off. The crowd burst into a spontaneous rendition of the Marseillaise (the French national anthem). And one of Rostand’s bitter rivals wrote in his journal that night, “Flowers, nothing but flowers, simply all the flowers for our great romantic poet.”12 Coquelin, the actor who had called the play a masterpiece, would go on to play Cyrano in 995 productions during his lifetime. According to Lloyd, Cyrano de Bergerac was the most unanimous triumph in the history of the theater in France.

But the forces of cynicism and naturalism nevertheless continued to take an ever-firmer hold on French theater and culture. Rostand, like his own hero, Cyrano, felt compelled to fight them with all he had and to champion the spirit of idealism that he thought made life worth living. Lloyd says, “He did not wish to replace reality by a dream, he wanted to enhance reality by means of a noble ideal . . . to send [people] out of the theater with a more noble, more spiritual attitude toward life.”13

Meanwhile, Cyrano de Bergerac was such an enormous success that Rostand became a household name, and he had to move to the countryside to escape the pressures of celebrity. He fell in love with Cambo-les-Bains, a pastoral region near the border of Spain. There, Lloyd says, “All the poetry of nature had suddenly entered him. He was delighted . . . as if he had acquired another treasure for his poetic soul.”14

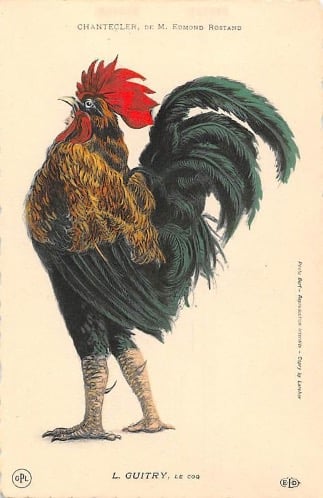

One day, as he was out walking in the country, a barnyard scene caught his eye. A blackbird hopping in a cage seemed to be mocking a cock that had just blithely entered the scene. The blackbird was the cynic, the cock the idealist. And from this germ grew the idea for his next play, Chantecler, another to be written in lyrical verse, whose flamboyant hero, this time, would be a rooster: a proud, idealistic, poetic rooster who sings in exalted praise of the sun. It would star Coquelin, who had played the swashbuckling hero of Cyrano to such perfection, and whose nickname happened to be “le Coq.”

When Rostand presented this idea to “Le Coq,” the actor was more skeptical. He said, unbelieving, “Is this serious?” And Rostand responded in a grave tone, “Very serious. Indeed.”15 An hour later, Coquelin was entirely won over. Tragically, he died before he could ever play the part, and with the script in his hands.

Lloyd says,

In his cockerel hero, Rostand was . . . portraying himself. Both are poets, with poets’ hearts and imaginations. But most of all, Chantecler’s devotion to his work and his duty of bringing light to banish the darkness of materialism and cynicism, is what Rostand felt to be his own duty.16

So, I am going to end our time together with Chantecler’s immortal “Hymn to the Sun,” a poem that, in its original exquisite, lyrical French has been memorized by children for more than a century.

Because it calls upon all the subtle resources of language, poetry defies translation. I have read the entirety of this play in not one, not two, but three translations, and from the little French I can read to compare, there is simply no comparison. But I think the one I have selected to share with you is the most faithful to the beauty and spirit of the original. It happens to be a translation by Kay Nolte Smith, who at one time was friends with Ayn Rand and wrote for the Objectivist newsletter.

Chantecler is a rooster whose cry raises the sun and banishes darkness from the earth. Rostand is a poet whose verses champion the noble and decry the darkness of cynicism. In the “Hymn to the Sun,” listen for the theme of this and all of Rostand’s work: “An ordinary life lived by the light of a great ideal . . . is made glorious . . . just as the earth is transformed by the light of the sun.”17 Sit back and bask in the warm light of the “Hymn to the Sun.”

You dry the tears of the tiniest weed with ease,

You bring dead flowers to life in the butterfly;

You warm the wind that cajoles the cherry trees

To shed their blooms, like destinies,

So they may grow and multiply.I worship you, o Sun! whose aureole,

To bless each brow and turn all nectar sweet,

Surrounds each cottage and fills each flower’s bowl;

You divide yourself but are always whole;

Like mother-love, you stay replete.I sing of you; take me as priest of your mass,

You who use soap bubbles as a place to dwell,

And often choose, when you sink below the grass,

To let the humble window-glass

Hold the torch of your last farewell.You make the sunflower lift her head to explore,

You burnish my brother-of-gold on the weather-vane,

You steal through the trees, and down through the leaves you pour

A shifting, drifting golden floor

Whose beauty footsteps would profane.You glaze the pottery jug with a single stroke,

You make a flying flag of a drying towel,

The haystack, thanks to you, wears a golden cloak,

And her little sister, the beehive, woke

This morning wearing a golden cowl.Glory to you on the fields! Upon the vines!

From the tops of the hills to the valley your blessing prevails!

On the wing of the swan, in the eye of the lizard it shines!

O you who draw the broad outlines

And render in the last details!For all you touch you cut out a darker twin

Who stretches and goes to bed at her sister’s feet;

You double the number of things we can revel in,

For each has a shadow next-of-kin

Who’s often lovelier to meet.You fill the air with scent, the stream with fire.

You make the bush a place where a god may light.

You turn the gloomy tree to a sacred choir.

Without you things could not aspire

Past what they are, to what they might!

I close with this poem, because Rostand is showing us that what the sun can do for reality, poetry can do for life. It can inspire us with ideals, reveal the depth beyond the surface, burnish our lives with beauty, turn the simple into the sacred, and make us aspire past what things are to what they might. I hope that is something you have experienced today, and I hope it is something you will experience again and again in the time to come.

Click To Tweet

You might also like

Endnotes

1. Sidney Colvin, Keats (London: MacMillan and Co., Ltd., 1909), 361.

2. Mary Robinson, “Dante Gabriel Rosetti,” Harper’s Magazine, vol. 65, January 1, 1882, Harper’s Magazine Foundation, 696.

3. Elizabeth Drew, Poetry: A Guide to Its Understanding and Enjoyment (New York: W. W. Norton, 1962), 29.

4. Victor Hugo, Ninety-Three (Cresskill, NJ: Paper Tiger Press, 2002), 328.

5. Drew, Poetry, 31.

6. “‘Surprised by Joy—Impatient as the Wind’ Analysis,” EliteSkills.com, http://www.eliteskills.com/analysis_poetry/Surprised_by_Joy_Impatient_as_the_Wind_by_William_Wordsworth_analysis.php (accessed January 29, 2020).

7. Maria Popova, “Love After Life: Nobel-Winning Physicist Richard Feynman’s Extraordinary Letter to His Departed Wife,” BrainPickings, https://www.brainpickings.org/2017/10/17/richard-feynman-arline-letter/ (accessed January 29, 2020).

8. I translated this poem from the French myself. Because I wanted to preserve the meter and rhyme, it is not an exact translation. But I think it remains true to the spirit of the original.

9. The play was Ubu Roi by Alfred Jarry.

10. Sue Lloyd, The Man Who Was Cyrano (Minehead, UK: Genge Press, 2013), 114.

11. Lloyd, The Man Who Was Cyrano, 136.

12. Lloyd, The Man Who Was Cyrano, 139.

13. Lloyd, The Man Who Was Cyrano, 86.

14. Lloyd, The Man Who Was Cyrano, 207.

15. Marco Francis Liberma, The Story of Chantecler: A Critical Analysis of Rostand’s Play (New York: Moffat, Yard and Co., 1910), 8.

16. Lloyd, The Man Who Was Cyrano, 220.

17. Lloyd, The Man Who Was Cyrano, 223.

![[TEST] The Objective Standard](https://test.theobjectivestandard.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/logo.png)