Those who would give up essential liberty, to purchase a little temporary safety, deserve neither liberty nor safety. —Benjamin Franklin

In February 2004, nineteen-year-old Mark Zuckerberg launched the Harvard-only social network TheFacebook from his dorm room. A couple of days later he thought, “You know, someone needs to build a service like this for the world,” and with the help of friends, he quickly scaled it to include other colleges. Initially, he was hoping for four- to five-hundred users, but within a few months the site had a hundred thousand. He soon dropped out of Harvard and moved to Silicon Valley to grow the project, becoming the world’s youngest self-made billionaire by the age of twenty-three. “It’s not because of the amount of money,” he told an interviewer around that time. “For me and my colleagues, the most important thing is that we create an open information flow for people.”1

And Facebook has done so for billions the world over, helping businesses find new customers and talent, connecting far-off soldiers with loved ones back home, bringing toddlers’ first steps and words to distant grandparents, and reuniting friends after decades of silence.

When, in 2004, Zuckerberg asked “who knows where we’re going next?,” he couldn’t have imagined that, seven years later, during the Arab Spring, Facebook would carry “a cascade of messages about freedom and democracy across North Africa and the Middle East,” as one researcher put it.2 No one could have foreseen that in 2012, after Hurricane Sandy devastated the New Jersey coast, residents of the Garden State would use Facebook to persuade local legends Bruce Springsteen and Jon Bon Jovi to play a benefit concert. Or that in 2013, when jihadists bombed the Boston Marathon, those desperate for news from friends and family would turn to Facebook. Or that in 2014, the ALS Association would use Facebook to popularize its “ice-bucket challenge,” raising more than $220 million to fight amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.

But the “open information flow” facilitated by Facebook and other platforms has also raised an important debate about the “social responsibility” of social-media companies. That’s because, despite worries about “echo chambers,” platforms have connected people with, among others, their enemies: conservatives with “Progressives,” Christian fundamentalists with atheists, capitalists with statists, neo-Nazis with Jews. And instead of facilitating constructive dialogue, social media often seems to bring out the worst in people. It’s never been easier to hurl nasty thoughts out into the world without reflection, and doing so gives users a jolt of feedback that many find rewarding. Such platforms also provide massive audiences to those who prioritize their agendas over the truth, making them powerful tools for spreading falsehoods and lies. And given that people all over the world now rely on social media for news, some argue that these companies should do more to moderate content—while others say that content moderation is “censorship” and that they ought to back off.

Many are calling on government to enforce these views, and they suggest that the future of civil society depends on massive new regulations on social-media companies. In a recent speech delivered to the Anti-Defamation League, for instance, English actor Sacha Baron Cohen eloquently summarized the case for government intervention. He argued that tech companies use algorithms that “amplify the type of content that keeps users engaged—stories that appeal to our baser instincts and that trigger outrage and fear.” He concludes that “by now it’s pretty clear, they cannot be trusted to regulate themselves,” so “as with the Industrial Revolution, it’s time for regulation and legislation to curb the greed of these hi-tech robber barons.”3

It’s no doubt true that some social-media companies (or particular individuals at these companies) have done shady, even despicable things, and some antipathy toward them is certainly reasonable. Facebook, for one, has at times been careless with user data, most notably in what became the Cambridge-Analytica scandal. But much of today’s anger toward social-media companies is misplaced.

Consider the response to a massive 2018 study that reported that on Twitter, “Falsehood diffused significantly farther, faster, deeper, and more broadly than the truth in all categories of information, and the effects were more pronounced for false political news.”4 Some of social media’s detractors claimed that the study is evidence that, as Cohen charges, platforms use algorithms that amplify divisive content to keep users engaged. This turned out to be little more than an eloquent demonstration of what the scientists who conducted the study actually concluded: “false news spreads more than the truth because humans, not robots [including Twitter’s algorithms], are more likely to spread it.” So, although people were quick to blame Twitter, the spread of false news “might have something to do with human nature,” according to the study’s lead scientist, Soroush Vosoughi of MIT.5 (“Falsehood flies, and the Truth comes limping after it,” said Jonathan Swift more than three hundred years ago. Of course people have free will and the choice to focus on truth and accuracy. But free will goes both ways, and many choose to advance false ideas, or at least ideas they don’t know to be true.)

The reaction to this study illustrates a broad trend. By and large, those who rage against social-media companies disregard the incredible values these platforms provide, and they aim blame at the wrong people. Worse, though, many of the solutions proposed are far more dangerous than the problems they purport to solve.

Let’s examine some of the most impassioned charges against social-media companies.

The Genocide of Rohingya Muslims in Myanmar

Ruled by military regimes since 1962, the Southeast Asian nation of Myanmar held parliamentary “elections” in 2010, and retired general Thein Sein was elected president.6 After Sein allowed some outside telecom firms to compete with the country’s single, state-run provider, prices plummeted and internet usage skyrocketed from 1.3 million mobile users in 2011 to 18 million today—nearly all of whom reportedly are Facebook users. Indeed, according to a United Nations report, in Myanmar, “for most users, Facebook is the internet.”7

The influx of Western technology, however, has not been accompanied by an influx of Western values, such as the idea that all men have inalienable rights. In Myanmar, much of the majority Buddhist population views the Rohingya Muslim minority as subhuman, and many use Facebook to promote that view. One user posted an image advertising a Rohingya restaurant with the caption, “We must fight them the way Hitler did the Jews, damn kalars [a derogatory term for a Muslim]!” Commenting on news of a Rohingya attack on police, another Facebook user posted, “These non-human kalar dogs . . . are killing and destroying our land, our water and our ethnic people. . . . We need to destroy their race.”8

Many of the accounts posting such messages have been traced back to Myanmar’s military, which devoted hundreds of its personnel to the anti-Rohingya social-media campaign.9 Since August 2017, about seven hundred thousand Rohingya have fled to Bangladesh, from whence the military claims they came illegally. Further, Myanmar’s military reportedly has murdered some twenty-four thousand Rohingya, leading the United Nations to accuse it of genocide.10

However, some commentators direct their ire not at the Burmese military but at Facebook, arguing that the company should all along have been doing more to remove such posts. Indeed, in the same speech quoted earlier, Cohen said that Facebook “facilitated [a] genocide in Myanmar” and that Americans ought to tell company executives, “do it again and you go to jail.”11

It’s certainly true that messages intended to induce violence violate Facebook’s community standards, and company representatives concede that they responded too slowly to such messages on their platform in the region.

Moreover, unless responding to an aggressor, no one anywhere has any legitimate right to threaten others with physical force. In the United States, what the courts call “true threats”—ones that threaten people with bodily harm—are properly illegal.12

For an indication of the damage that such threats cause, consider the case of ex-Muslim cartoonist Bosch Fawstin, who left Islam after learning just how violent and antilife the religion is. In his efforts to expose the true nature of Islam and defend free speech, he has drawn the “prophet” Muhammed more than three hundred times, and he won the first-ever Muhammed cartoon contest in Garland, Texas—where two jihadists showed up to kill him and all others present. (Thankfully, the jihadists were killed before they could kill anyone.)

Since then, Muslims around the world have sent Fawstin thousands of death threats. Nowadays, he spends little time in public places, is not a regular at any local restaurants, and does not book speaking tours—not because he doesn’t want to do these things, but because he cannot do them without risking his life.

Threats of physical force violate peoples’ rights by keeping them from pursuing their happiness in accordance with their own judgment. People can’t live freely and act on their judgment if they rationally believe that others will kill or maim them for doing so.

So, it’s commendable that many social-media companies expend massive resources in efforts to remove threats from their platforms. Reportedly, Facebook’s safety team now “is made up of around 30,000 people, about 15,000 of whom are content reviewers around the world.”13 And in response to the escalating violence in Myanmar, Facebook has added more than one hundred Burmese speakers to the safety team.

This, of course, is a smart business move: Who wants to use a platform on which they feel unsafe? And it’s a convenient characteristic of Facebook’s business that, whereas a restaurant owner would have to call the police to physically remove loudly menacing National Socialists, for instance, Facebook can simply delete a user’s posts or account.

But this is an endless game of whack-a-mole. Meaningfully reducing rights-violating threats requires legally prosecuting rights violators. And ultimately, it is the job of government—not private companies—to protect individual rights. If a government refuses to protect its peoples’ rights, if it systematically violates their rights—as has every iteration of Myanmar’s government since the country gained independence from Britain in 1948—then people ought to flee, as the Rohingya are doing, or revolt—as Americans once did.

But it is a bizarre injustice to threaten Facebook executives with regulations or jail time—both of which would be violations of their rights—for failing to do the job of Myanmar’s government. Suppose a restaurant owner calls police to eject Nazis who are frothing at the mouth with threats of violence, but they never show up—or they do show up and join in threatening his patrons. Would it be rational to fine or imprison him? Of course not.

If providing people with life-enhancing technology that can be harnessed for ill is “facilitating” evil, as Cohen suggests, then history’s heroes of innovation are actually villains, one and all. By this logic, Johannes Gutenberg, the inventor of the printing press, “facilitated” Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf, Mao’s “little red book,” and Karl Marx’s Das Kapital—each of which has motivated an incalculable number of murderers. By inventing the modern megaphone and movie camera, Thomas Edison “facilitated” the spread of propaganda by scores of dictators. And so on for every hero of human progress who ever lived.

Of course, innovators such as these deserve gratitude and recognition—not threats of fines and jail time.

Perhaps Facebook could have responded more quickly to those who violated the platform’s policies and used it in nefarious ways, but the company most certainly did not violate anyone’s rights—Myanmar’s genocidal military did.

2016 Russian Election Meddling

Another charge against Facebook concerns Russia’s meddling in the 2016 U.S. presidential election. In November 2017, a company representative told investigators about something Facebook had recently discovered: Between January 2015 and August 2017, the Internet Research Agency (IRA), a Russian troll farm funded by Vladimir Putin’s associate Yevgeny Prigozhin, created 470 Facebook accounts that reached 126 million people via 80,000 posts and $100,000 in Facebook ads. Special Counsel Robert Mueller concluded that the IRA’s Kremlin-backed social-media campaign aimed to promote Donald Trump, disparage Hilary Clinton, and “amplify political and social discord” prior to the election.14

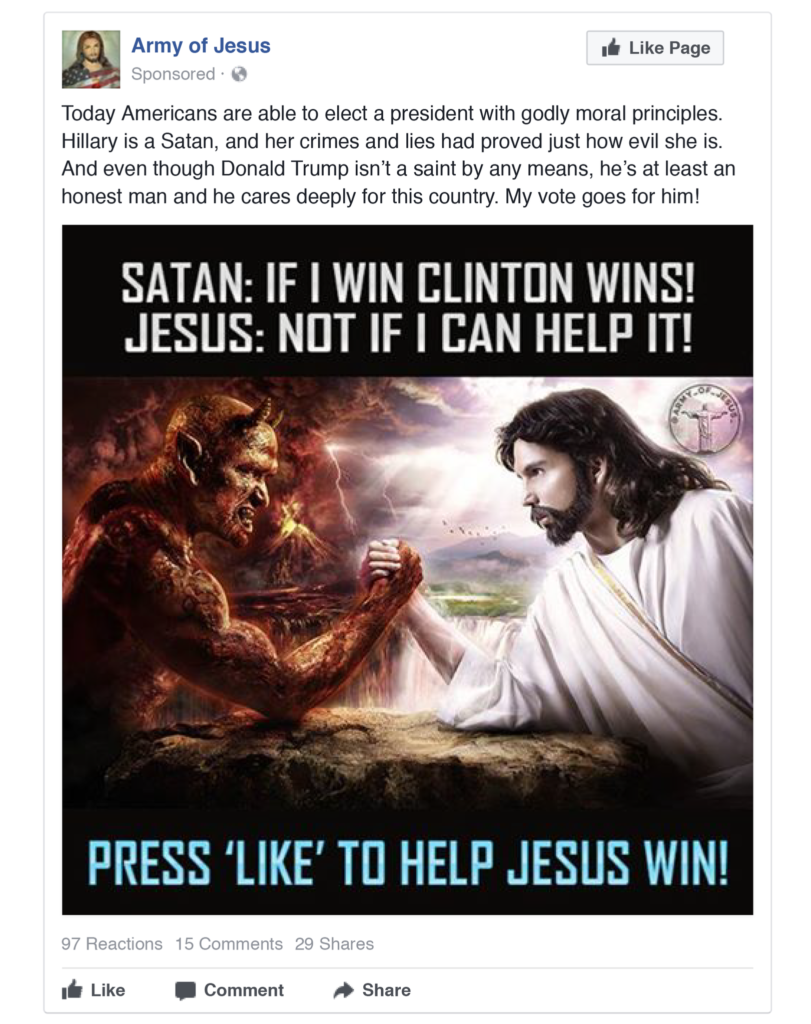

One example of such tactics comes from the IRA account, Army of Jesus, which posted an image of Satan and Jesus arm wrestling. Overlaid text read, “Satan: If I win Clinton wins! Jesus: Not if I can help it! Press ‘Like’ to help Jesus win!” The caption called Hilary Clinton “a Satan” and said that “even though Donald Trump isn’t a saint by any means, he’s at least an honest man and he cares deeply for this country. My vote goes for him!”15

Set aside the question of whether the IRA’s campaign worked and actually persuaded anyone to vote for Donald Trump or to abstain from voting for Hilary Clinton. Either way, it is the U.S. government’s responsibility to protect American citizens’ rights, which entails protecting U.S. elections from foreign interference. The U.S. government recognized this responsibility by ordering Mueller’s investigation and by subsequently indicting and freezing the American assets of Prigozhin, three of his companies (including IRA), and twelve IRA employees/contractors. Jailing or materially stifling rights violators obviously decreases rights violations—if not immediately, then in the long run.

But addressing the problem at its source did not satisfy everyone. Cohen, whose comments are again indicative of a widespread view, said that Facebook “allowed [a] foreign power to interfere in our elections”—another reason he thinks Americans should threaten the company’s executives with jail time.

This view, though, implies that it’s the job of private companies to detect and deflect the covert actions of hostile nations. That is, in addition to providing a great user experience for nearly 2.5 billion users, Facebook ought to establish a Department of Homeland Security.

Absurd.

The question is not “What should Facebook have done for its country?” but “What should the country—specifically the government, whose job it is to protect Americans’ rights—have done for Facebook?”

The notion that protecting U.S. elections from foreign interference requires censoring the ideas that foreigners share on social media is dubious; it’s typically premised on the belief that Americans are incapable of assessing ideas for themselves. But if such action ever is necessary to protect individual rights, doing so is the government’s job, not Facebook’s.

However, in a mixed economy, the line between private action and government force is often blurred—as it has been in this case. Facebook has implemented procedures that require identity verification from anyone wishing to place political ads.16 Whether it did so of its own accord or because bureaucrats pressured it to do so is unclear.

What is clear is that no evidence indicates that Facebook knowingly sought to influence the 2016 election in Trump’s favor. It is a well-known fact that many executives and employees at social-media companies, Facebook included, historically have supported so-called “Progressive” candidates and policies. Data from the Wall Street Journal shows that in 2015–16, Facebook employees donated roughly one hundred times more money to Hilary Clinton’s campaign than they did to Donald Trump’s. As Mark Zuckerberg recently said during his Senate testimony, Silicon Valley is “an extremely left-leaning place.”17

Which brings us to the next charge against social-media companies.

Moderation Bias and Censorship

Despite his admission that Silicon Valley is “an extremely left-leaning place,” Zuckerberg denies that his company’s content moderation practices reflect this. Nonetheless, President Donald Trump, Senators Josh Hawley and Ted Cruz, plus commentators such as Dennis Prager, Ben Shapiro, Dave Rubin, Eric Weinstein, Sam Harris, and others claim that the moderation practices of social-media companies demonstrate an unmistakable anti-conservative bias. Many also claim that this bias is censorship and that it violates freedom of speech.

I am continuing to monitor the censorship of AMERICAN CITIZENS on social media platforms. This is the United States of America — and we have what’s known as FREEDOM OF SPEECH! We are monitoring and watching, closely!!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) May 3, 2019

Hawley has responded with a bill that would revoke the legal protection that keeps social-media companies from being sued for things that users post. He argues that section 230 of the Communications Decency Act (CDA), which currently protects platforms from being sued for libel committed by users, was intended to recognize and accommodate the difference between edited media (such as newspapers) and unedited forums. But because platforms choose to moderate their content, he says, they should be treated the same as newspapers. Only platforms that prove to the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) that they are “politically neutral” should retain the current level of protection, argues Hawley.

Of course, the reason newspapers and magazines rightfully are responsible for their content is that they create it. They pay people to create, edit, and shape the content they publish—including any libelous content. On the other hand, social-media companies don’t primarily create content—they host it. Whereas a newspaper is akin to an artist’s gallery wherein each piece is finely crafted by the artist, a social-media platform is more like a massive, privately owned bulletin board. The difference between publications and social-media platforms is one of kind, not of degree, a fact that section 230 of the CDA recognizes. In light of this difference, justice demands that users who create content, not platforms that host it, be held responsible for that content—as they are under current law.

Social-media companies may decline to use their property to host certain types of content for any reason, including that such content is antithetical to their values. This doesn’t change the fact that they did not create the content that they do choose to host, nor that those who create that content—not those who host it—should be responsible for it.

When social-media companies refuse to host certain types of content (or when they reduce the reach of such content), this is not an act of censorship or a violation of anyone’s right to free speech. Censorship refers only to government action. Freedom of speech means that the government may not suppress certain views or inhibit the individuals who express them. If the government bans a book, an artwork, or a speaker, that is censorship.

It’s not censorship if a Christian publisher rejects an atheist’s book, or if a left-leaning newspaper doesn’t hire (or fires) a freedom-loving columnist, or if a Romantic art gallery refuses to display a banana duct-taped to a wall, or if a social-media platform bans Alex Jones.

The right to speak one’s mind is not a right to a book contract, a newspaper column, a gallery exhibit, a social-media platform, or to any product of another person’s effort. A person’s right to speak his mind is not a right to another person’s property or support. There can be no right that violates another person’s rights.

It may very well be and probably is the case that social-media moderation is biased against some viewpoints or types of content, just as the New York Times and Fox News are. Facebook, for one, has announced that it penalizes “sensationalist and provocative content” so that it “gets less distribution and engagement,” and some argue that the company’s enforcement of this policy is lopsided, penalizing provocative content supporting one side of an issue but not the other.18

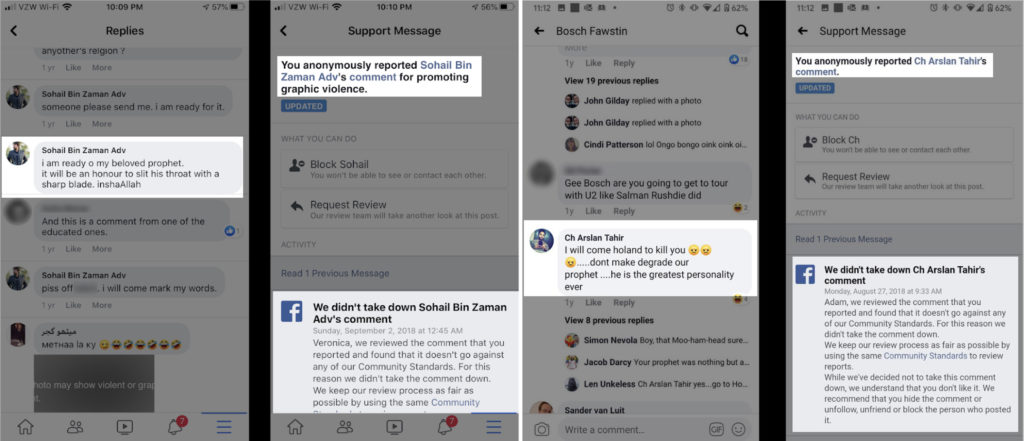

For instance, Bosch Fawstin, mentioned earlier, certainly produces provocative content, and Facebook has deleted his account on occasion. However, he also regularly receives death threats on Facebook, and when he and others have reported these, Facebook has replied that these threats do not violate the company’s community standards. Such a double standard—especially given Facebook’s protestations of neutrality—is frustrating.

Two death threats that Muslims sent to Bosch Fawstin that Facebook said did not violate its community standards

Fortunately, anyone who thinks that social-media companies do a poor job of moderating content has a lot of options for what to do about it. For instance, he is free to use the tools provided by platforms for unfollowing, blocking, and reporting content; he can stop using a platform altogether; he can reach out to social-media companies and advocate change; or he can create his own platform that incorporates his values and compete with other companies for users (as Dave Rubin is doing).19

What he cannot do in a rights-protecting, civil society is force others to supply him with a social-media platform moderated according to his preferences—as Hawley’s bill would do if enacted. Such a law would subject social-media companies to the following ultimatum: Be “politically neutral”—by giving up your right to moderate your platform as you see fit—or open yourself up to lawsuits for crimes you did not commit. This effectively would deprive social-media companies of their property rights. For instance, platform owners may not want to host content from the American Nazi Party (a real political party, established in 1960). But choosing not to may lose the company its “political neutrality” certification and thereby constitute legal suicide by opening it up to libel suits for user’s posts.

Moreover, the “political neutrality” standard would be interpreted and enforced by FTC commissioners—themselves political stakeholders nominated by the president to serve seven-year terms. Social-media companies would have no means of knowing in advance what actions this ever-changing cast of partisan bureaucrats will consider to be “politically non-neutral” and so will be forced to curry favor to avoid an avalanche of lawsuits. Thus, five commissioners would be given massive power to influence speech on the internet. As Representative Justin Amash says, “This legislation is a sweetheart deal for Big Government. It empowers the one entity that should have no say over our speech to regulate and influence what we say online.”20

This legislation is a sweetheart deal for Big Government. It empowers the one entity that should have no say over our speech to regulate and influence what we say online. https://t.co/IMtBvlKkfY

— Justin Amash (@justinamash) June 20, 2019

Of all the senseless reactions to the issues surrounding social-media companies, such actual threats to property rights and freedom of speech are the most ominous signs for the future of civil society.

The Future of Civil Society

While communist China strives to perfect its “Great Firewall” and begins exporting its surveillance and censorship toolbox, Western countries are beginning to take action against social-media companies.

In 2017, German lawmakers passed NetzDG, which requires that social-media sites remove “manifestly unlawful” content within twenty-four hours of being notified—or pay a fine of up to $55 million. “Unlawful content” includes posts that “incite hatred,” depict or “describe cruel or otherwise inhuman acts of violence,” or that use “titles, professional classifications and symbols . . . without authorization.”21 Before the law was passed, leaders of several industry and free-speech groups warned that “the draft law would unquestionably undermine freedom of expression.”22

On January 1, 2018, the day the law went into effect, Twitter complied with a request to block the account of Beatrix Von Storch, leader of the Alternative for Germany political party, after she criticized the police department of North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW, a German state) for tweeting a New Year’s greeting in Arabic. In 2015, a Muslim rape gang committed twenty-four mass sexual assaults in Cologne (Köln), a city in NRW.23 Von Storch’s tweet asked, “What the hell is wrong with this country? Why is the official page of the police in NRW tweeting in Arabic? Are they seeking to appease the barbaric, Muslim, rapist hordes of men?”

#PolizeiNRW #Köln #Leverkusen

تتمنى الشرطة في كولن لجميع الناس في منطقة كولن وليفركوزن والمدن الأخرى إحتفالاً سعيداً بعام 2018 الجديد.

https://t.co/G5erMWFNQyرأس السنة 2017 ـ لمزيد المعلومات: # pic.twitter.com/BGxs4Kew7K— Polizei NRW K (@polizei_nrw_k) December 31, 2017

Shortly thereafter, the German satirical magazine Titanic parodied Von Storch’s tweet—only to have its account blocked as well. “Faced with short review periods and the risk of steep fines,” writes Human Rights Watch, “companies have little incentive to err on the side of free expression.”24 Nonetheless, says Till Steffen of Germany’s Greens party, “If we want to effectively limit hate and incitement on the Internet, we have to give the law more bite and close the loopholes.”25

Despite arguments by David Kaye (United Nations special rapporteur on freedom of opinion and expression) that NetzDG violates international human rights law by forcing private companies to censor citizens on behalf of the government,26 UK officials are working on a law to rival Germany’s—with the goal of making the UK “the safest place in the world to go online.”27 In April 2019, then-Prime Minister Theresa May said regulators were considering fining tech firms, blocking sites, and “impos[ing] liability on individual members of senior management” at companies that failed in their “duty of care” to users.28

The government’s “Online Harms” white paper explains, “There is a lot of illegal and harmful information and activity online. People in the UK are worried about what they see and experience on the internet. This information can be a threat to the safety of the UK and to the safety of our people, especially our children.” The paper also expresses a worry that online platforms can be used to oppose “our democratic values,” which it defines as “our ways of thinking, such as everyone being free, everyone being treated equally and fairly and freedom of speech.” (The authors don’t explain how a law prohibiting freedom of speech will protect freedom of speech.)

France is not far behind. Its digital affairs minister, Cédric O, recently told Wired that although the country’s new digital tax on some tech companies “is politically and symbolically important,” it is a meager indicator of what’s to come.29 “Tech platforms have a footprint in our economies and our democracies that is a huge challenge for public power,” he said.30

Unlike Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders, O doesn’t want to break up tech companies. His inspiration comes from another American, former FCC chairman Tom Wheeler, whose slogan is, “Don’t break them up, break them open,” by which he means, give all aspiring tech firms access to “the databases full of information about you and I [sic].” Wheeler holds that sharing users’ personal data liberally will prevent social-media monopolies: “Requiring competitive interconnection to databases would have the effect of an ‘internal break up’ by going after the source of its [sic] market control.”31

Some American academics agree. Duke University professor Philip Napoli argues that the user data that social-media companies collect and monetize is a “public resource.” Thus, just as the FCC is empowered to force broadcasters to “serve the public interest” while using the supposedly public resource of airwaves, so it ought to be empowered to do the same with tech companies that leverage user data—even if bureaucrats must “infringe upon their First Amendment freedoms” to do so.32 Harvard’s Gene Kimmelman adds that we need “a new expert regulator equipped by Congress” to selectively regulate tech companies based on market dominance.33

Many of the bureaucrats and commentators behind these laws and initiatives against social-media companies share essentially the same tactic. They blame social-media companies for not doing what governments are supposed to do—protect individual rights—and then rationalize that this supposed failure is grounds for doing what governments are not supposed to do—violate individual rights.

As Germany’s example illustrates, this is not a path toward preserving civil society but of destroying its foundation. Germany has given government the power to force social-media companies to censor citizens on its behalf, thus simultaneously violating the rights of platforms and their users.

If we want to safeguard the future of civil society, then we must defend the rights of social-media companies. True, social media at times may carry messages we abhor. Shooting the messenger, though, is not a solution but a path toward statism.

When we do witness others spewing animosity online, we might think of the story of Meghan Phelps-Roper. Raised in the ultra-fundamentalist Westboro Baptist Church (WBC), she was parading with signs harassing homosexuals before she could read. Her church soon became infamous for picketing the funerals of gay men who died of AIDS and of fallen soldiers, whose deaths WBC members believe are God’s punishment for America’s increasing acceptance of homosexuality.

A little more than a decade after Meghan’s first picket, she brought the church’s vile message to Twitter—but a funny thing happened. Many attacked the young bigot, of course, but a few people showed concern, asked her questions, and engaged with her civilly. They “didn’t abandon their beliefs or their principles, only their scorn,” she recalls.34 In time, these people cracked the shell of ludicrous, self-righteous dogma Meghan had been raised within. She began to question her beliefs—and to drop them.

Three years after first logging onto Twitter, Meghan left the church. Once a toddler spreading hate for “God’s enemies,” she now educates audiences about reaching the indoctrinated through civil discourse, contending that many seeming psychopaths are, in fact, “psychologically normal people that have been persuaded by bad ideas.”35 In 2015, she tweeted, “Enlightenment. Kindness. Friendship. & the love of my life. All from @Twitter.”36

Yes!

Enlightenment.

Kindness.

Friendship.

& the love of my life.

All from @Twitter.https://t.co/jUopirmBhZ@michaelianblack @NewYorker— Megan Phelps-Roper (@meganphelps) November 16, 2015

“If you want to make the world a better place,” sang Michael Jackson, “take a look at yourself, and then make a change.” Similarly, if we want to safeguard civilization, we might start by looking at our own behavior online and ensuring that we are not a part of the problem. Indeed, we can be part of the solution by modeling civil discourse—and by defending the rights that separate civil society from the “brave new world” now rising around it.

Click To Tweet

You might also like

Endnotes

1. “Mark Zuckerberg,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mark_Zuckerberg (accessed December 10, 2019).

2. Catherine O’Donnell, “New Study Quantifies Use of Social Media in Arab Spring,” University of Washington, September 12, 2011, https://www.washington.edu/news/2011/09/12/new-study-quantifies-use-of-social-media-in-arab-spring/.

3. Sacha Baron Cohen, “Read Sacha Baron Cohen’s Scathing Attack on Facebook in Full: ‘Greatest Propaganda Machine in History,’” Guardian, November 22, 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2019/nov/22/sacha-baron-cohen-facebook-propaganda.

4. Soroush Vosoughi, Deb Roy, and Sinan Aral, “The Spread of True and False News Online,” Science 359, no. 6380 (March 9, 2018), https://science.sciencemag.org/content/359/6380/1146.

5. Robinson Meyer, “The Grim Conclusions of the Largest-Ever Study of Fake News,” Atlantic, March 8, 2018, https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2018/03/largest-study-ever-fake-news-mit-twitter/555104/.

6. Popular leader Aung San Suu Kyi was held under house arrest and barred from the race.

7. Elise Thomas, “Facebook Keeps Failing in Myanmar,” ForeignPolicy.com, June 21, 2019, https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/06/21/facebook-keeps-failing-in-myanmar-zuckerberg-arakan-army-rakhine/.

8. Steve Stecklow, “Inside Facebook’s Myanmar Operation: Hatebook,” Reuters, August 15, 2018, https://www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/myanmar-facebook-hate/.

9. Paul Mozur, “A Genocide Incited on Facebook, with Posts from Myanmar’s Military,” New York Times, October 15, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/15/technology/myanmar-facebook-genocide.html.

10. “Myanmar Rohingya: What You Need to Know about the Crisis,” BBC, April 24, 2018, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-41566561; D. Parvaz, “One Year and 10,000 Rohingya Deaths Later, UN Accuses Myanmar of ‘Genocide,’” ThinkProgress, August 27, 2018, https://thinkprogress.org/10000-rohingya-deaths-united-nations-accuses-myanmar-genocide-f19d785bbece/.

11. Cohen, “Read Sacha Baron Cohen’s Scathing Attack on Facebook in Full.”

12. The U.S. Ninth Circuit Court describes true threats as threats that a “reasonable person” would interpret as “expression[s] of intent to inflict bodily harm upon” the person threatened. See “Threats of Violence against Individuals,” Legal Information Institute, Cornell Law School, https://www.law.cornell.edu/constitution-conan/amendment-1/threats-of-violence-against-individuals (accessed January 14, 2020).

13. “Facts about Content Review on Facebook,” Facebook, December 28, 2019, https://about.fb.com/news/2018/12/content-review-facts/.

14. Robert S. Mueller III, “Report on the Investigation into Russian Interference in the 2016 Presidential Election,” vol. 1, U.S. Department of Justice, March 2019, https://www.justice.gov/storage/report.pdf.

15. Scott Shane, “These Are the Ads Russia Bought on Facebook in 2016,” New York Times, November 1, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/11/01/us/politics/russia-2016-election-facebook.html.

16. “Get Authorized to Run Ads about Social Issues, Elections or Politics,” Facebook, https://www.facebook.com/business/help/208949576550051?id=288762101909005 (accessed January 15, 2020).

17. In fact, during the same period in which Facebook is accused of “allow[ing a] foreign power to interfere in our elections,” Zuckerberg ousted Facebook executive Palmer Luckey, a libertarian, after he donated $10,000 to a pro-Trump organization. Although the company denies Luckey was fired for his political views, a crime in the state of California, the evidence indicates that he was: While Luckey’s future at Facebook was still in question, Zuckerberg personally drafted a letter that Luckey was asked to publish as his own, which distanced him from Trump and avowed support for Gary Johnson. See Kirsten Grind and Keach Hagey, “Why Did Facebook Fire a Top Executive? Hint: It Had Something to Do with Trump,” Wall Street Journal, November 11, 2018, https://www.wsj.com/articles/why-did-facebook-fire-a-top-executive-hint-it-had-something-to-do-with-trump-1541965245.

18. Mark Zuckerberg, “A Blueprint for Content Governance and Enforcement,” Facebook, November 15, 2018, https://www.facebook.com/notes/mark-zuckerberg/a-blueprint-for-content-governance-and-enforcement/10156443129621634/.

19. See locals.com for more information.

20. Justin Amash, Twitter, June 19, 2019, https://twitter.com/justinamash/status/1141513644758437888.

21. See “Chapter Seven, Section 130: Incitement to Hatred,” German Criminal Code, translated by Dr. Michael Bohlander, https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/englisch_stgb/englisch_stgb.html#p1246 (accessed December 11, 2019).

22. James Waterworth et. al., “Germany’s Draft Network Enforcement Law Is a Threat to Freedom of Expression, Established EU Law and the Goals of the Commission’s DSM Strategy—the Commission Must Take Action,” May 22, 2017, https://edri.org/files/201705-letter-germany-network-enforcement-law.pdf.

23. “2015–16 New Year’s Eve Sexual Assaults in Germany,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2015%E2%80%9316_New_Year%27s_Eve_sexual_assaults_in_Germany#Suspects (accessed December 10, 2019).

24. “Germany: Flawed Social Media Law,” Human Rights Watch, February 14, 2018, https://www.hrw.org/news/2018/02/14/germany-flawed-social-media-law.

25. Andrea Shalal, “German States Want Social Media Law Tightened,” Reuters, November 12, 2018, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-germany-hate-speech/german-states-want-social-media-law-tightened-media-idUSKCN1NH2HW.

26. Kaye writes, “While it is recognized that business enterprises also have a responsibility to respect human rights, censorship measures should not be delegated to private entities (A/HRC/17/31). States should not require the private sector to take steps that unnecessarily or disproportionately interfere with freedom of expression, whether through laws, policies or extralegal means (A/HRC/32/38). See David Kaye, “Mandate of the Special Rapporteur on the Promotion and Protection of the Right to Freedom of Opinion and Expression,” Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, June 1, 2017, https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Issues/Opinion/Legislation/OL-DEU-1-2017.pdf.

27. Sajid Javid and Jeremy Wright, “A Summary—Online Harms White Paper,” Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport, April 8, 2019, https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/online-harms-white-paper.

28. Amy Gunia, “U.K. Authorities Propose Making Social Media Executives Personally Responsible for Harmful Content,” Time, April 8, 2019, https://time.com/5565843/united-kingdom-social-media-regulations/.

29. Tim Simonite, “France Plans a Revolution to Rein in the Kings of Big Tech,” Wired, December 8, 2019, https://www.wired.com/story/france-plans-revolution-rein-kings-tech/.

30. Lydia Saad, “Americans Split on More Regulation of Big Tech,” Gallup, August 21, 2019, https://news.gallup.com/poll/265799/americans-split-regulation-big-tech.aspx.

31. Tom Wheeler, “Should Big Technology Companies Break up or Break Open?,” Brookings, April 11, 2019, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/techtank/2019/04/11/should-big-technology-companies-break-up-or-break-open/.

32. Philip Napoli, “What Would Facebook Regulation Look Like? Start with the FCC,” Wired, October 4, 2019, https://www.wired.com/story/what-would-facebook-regulation-look-like-start-with-the-fcc/.

33. Gene Kimmelman, “The Right Way to Regulate Digital Platforms,” Harvard Kennedy School, Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics, and Public Policy, September 8, 2019, https://shorensteincenter.org/the-right-way-to-regulate-digital-platforms/.

34. Megan Phelps-Roper, “I Grew up in the Westboro Baptist Church. Here’s Why I Left,” TED, February 2017, https://www.ted.com/talks/megan_phelps_roper_i_grew_up_in_the_westboro_baptist_church_here_s_why_i_left#t-21989.

35. Megan Phelps-Roper, “Sarah Sits down with an Ex-Member of the Westboro Baptist Church,” I Love You, America, YouTube, October 25, 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EmgZgHpv8Zs.

36. Megan Phelps-Roper, Twitter, https://twitter.com/meganphelps/status/666260922915246080 (accessed January 25, 2020).

[bctt tweet="Social media at times may carry messages we abhor. Nevertheless, if we want to safeguard the future of civil society, then we must defend the rights of @Facebook @Twitter @Google @YouTube and all other social media companies."]

![[TEST] The Objective Standard](https://test.theobjectivestandard.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/logo.png)