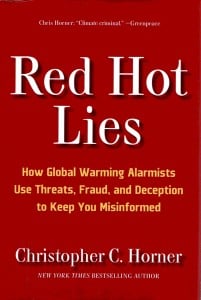

Red Hot Lies: How Global Warming Alarmists Use Threats, Fraud, and Deception to Keep You Misinformed by Christopher C. Horner. Washington, DC: Regnery Publishing, 2008. 407 pp. $27.95 (cloth).

I’m an environmental scientist, but I’ve never had time to review the “evidence” for the [man-made] causes of global warming. I operate on the principle that global warming is a reality and that it is human-made, because a lot of reliable sources told me that . . . Faith-based science it may be, but who has time to review all the evidence? (p. 318)

That is just one of many astonishing statements by global warming alarmists that Christopher C. Horner catalogs and analyzes in Red Hot Lies: How Global Warming Alarmists Use Threats, Fraud, and Deception to Keep You Misinformed. Horner amply demonstrates that the acceptance of such “faith-based science” is the modus operandi of many activists, journalists, and politicians—who want you to accept it too.

Horner exposes the tactics alarmists use to sell you on the faith and keep you ignorant of the facts surrounding alleged global warming. One such tactic is simple, premeditated deception:

Consider the example of Gore’s co-producer Laurie David, who followed [Gore’s documentary, An Inconvenient Truth] with a book aimed at the little ones. . . . [In the documentary] one ought to have suspected that Al Gore was up to something when he ran two lines [for CO2 concentration and temperature change] across the screen . . . claimed a cause-and-effect relationship, and then forgot to superimpose them. . . . Gore was correct to insist there was a relationship between the temperature line and the CO2 concentration line, as measured over the past 650,000 years. . . . The relationship, however, was the precise opposite of what he suggested: historically, it warms first, and then CO2 concentrations go up.

Gore’s wording and visuals were cleverly deceptive—he implied, without stating . . . that CO2 increases are followed by temperature increases. The reason he didn’t source his claim is that the literature doesn’t support it.

Somehow believing only the young would bother to open their [book] targeting children, David and [co-author Cambria] Gordon weren’t so clever. Their book included the two lines, but dared superimpose them, and even stated the phony relationship more outlandishly than Gore did in his film. The reason that temperature appeared to follow CO2 proved to be because they reversed the labels in the legend (pp. 199–200).

Horner shows that such deceptions are typical, not just of documentary producers and author-activists seeking to spread the faith, but also of so-called scientists and purportedly scientific organizations including, for instance, the UN’s Inter-Governmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Of the IPCC, Horner writes:

The unsupportable advocacy from these supposed sages of science begins with their threshold dishonesty of putting forth a lurid and alarming “summary,” drafted by a few dozen people who often are activists—and encouraging claims that these conclusions represent the consensus of thousands of “the world’s leading scientists” from the world over (p. 294).

These summaries, Horner shows, are written before scientists have submitted data. Even worse, it “appears that the IPCC intends to make the scientists . . . change their findings if they depart from the summary in order to bring them in line with it” (p. 304). The IPCC’s “Lead Authors” edit out inconvenient findings, such as the following two, which, according to one scientist, had intentionally been “included at the request of participating scientists to keep the IPCC honest.”

“None of the studies cited above has shown clear evidence that we can attribute the observed [climate] changes to the specific cause of increases in greenhouse gases.”

“No study to date has positively attributed all or part [of the climate change observed to date] to anthropogenic [man-made] causes” (pp. 300–301).

Unfortunately, these statements did not keep the IPCC honest. They were deleted from the report.

Horner shows that environmental journalists are in on the scam too. For example, journalists reporting on temperatures in the Arctic have compared the coldest year on record with the warmest year and then claimed that carbon dioxide emissions are the cause of the difference—despite research showing that over a more historically relevant period the Arctic has actually cooled. They have also reported that polar bear populations are facing a rapid decline, in spite of actual reports from Arctic biologists stating that “bear populations are exploding with some of the biggest cubs born on record” (p. 45).

Such nonobjective reporting is no accident, says Horner. It is an explicit policy of those seeking to defend the faith. As one alarmist succinctly puts it, “We have to offer up scary scenarios, make simplified, dramatic statements, and make little mention of any doubts we have. . . . Each of us has to decide what the right balance is between being effective and being honest” (p. 172). To be effective in “herding policymakers towards desired ends,” writes Horner, the alarmists must resort to dishonesty (p. 28).

In addition to dishonesty, the alarmists resort to ludicrous claims; for example, that an alleged scientific “consensus” on the question of global warming carries scientific weight. Horner quotes some better thinkers on the absurdity of this notion:

Financial Times columnist John Kay explained the oddity of “consensus” in science: “We do not say that there is a consensus over the second law of thermodynamics, a consensus that Paris is south of London or that two and two are four. We say that these are the way things are.” Professor Robert Carter makes the same point: “We do not usually say that there is a ‘consensus that the sun will rise tomorrow.’ Instead, the confident statement that ‘the sun will rise tomorrow’ rests upon repeated empirical testing and the understanding conferred by Copernican and Newtonian theory” (pp. 155–56).

Another thinker, meteorologist Anthony Watts, seeking not consensus but valid evidence regarding the temperatures in various regions of the planet, set out to check the reliability of the official temperature measurement stations across America. Horner relays Watts’ findings:

You see, there’s no such thing as “global temperature” or even “U.S. temperature.” There are, instead, weighted averages from adjusted readings from many different measuring stations. Now, clearly it matters how and how often instruments are maintained, and of course where they are sited. . . .

Watts had issued a call for individuals to photograph each of America’s 1,221 official surface stations. As the first snaps came in, he noticed a preponderance of ridiculously sited instruments. This yielded, among other shots, a priceless photo of a measuring station in Tahoe City, California, near the heat islands of a tennis court and parking lot. Oh, and it was five feet from a metal trash burn barrel. . . .

[It] has also shown us the great station in Hopkinsville, Kentucky: next to shrubbery, contrary to standards, which is child’s play compared to the fact that it abuts not just a brick building, but the chimney. The station overhangs not only a black asphalt pad but an air conditioning fan blowing hot air. The Weber barbeque grill right below, however, is the ultimate touch (pp. 267–68).

Of course, global warming alarmists do not take kindly to scientists who expose such things. In addition to smearing them as “deniers” (p. 61) or “tobacco scientists” (p. 66) or other epithets, alarmists attempt to silence dissenting scientists by moving them to a different area of research, cutting off their funding, or firing them. Horner points out that because the amount of taxpayer “money flowing into studying [climate change] is jaw-dropping” (p. 257), and because the penalty for disagreement is often the end of one’s career, “it is surely not coincidence that prominent researchers [only begin] speaking out against alarmism after retiring from their positions.” This includes NASA’s Joanne Simpson, a renowned scientist who began a speech on the subject by saying, “Since I am no longer affiliated with any organization nor receive any funding, I can speak quite frankly” (p. 72). Another scientist explains: “Young researchers keep their mouths shut, because of the fear [of] repercussions for their careers if they come out in favour of climate skepticism” (p. 76).

Horner shows that the repercussions can be more severe than the mere loss of one’s career. He relates incidents ranging from a scientist’s wheels falling off his car on two separate occasions shortly after he “came out in criticism of the environmental alarmists” (p. 70); to a columnist saying that “every time someone dies as a result of floods in Bangladesh, an airline executive should be dragged out of his office and drowned”; to a government official saying that “a certain shock treatment is needed [for global warming dissidents], but it would be best delivered with a two-by-four as a solid whack to [their] heads” (p. 69); to environmentalists calling for politicians who oppose the global warming agenda to be thrown in jail (p. 106); to environmentalists calling for “war crimes trials for [the skeptics]—some sort of climate Nuremberg” (p. 74); to “The head of the United Nations Environment Programme and longtime UN bureaucrat, Yvo de Boer, warn[ing] that ‘ignoring warming’ . . . [is] ‘criminally irresponsible’”; to “UN special climate envoy Dr. Gro Harlem Brundtland declar[ing] it ‘completely immoral, even, to question’ the UN’s claims to scientific consensus” (p. 308).

It is no wonder, as University of Auckland professor Chris de Freitas points out, that “relatively few scientists are willing to put their heads above the parapet . . . to paraphrase Voltaire, it is dangerous to be right when the authorities are wrong” (pp. 74–75). Christopher Horner faces that danger head-on and exposes the ways in which alarmists are “scaring you out of your liberties” (p. 210).

Although Red Hot Lies is haphazardly organized and occasionally lingers too long on issues of questionable relevance, the book is certain to prove valuable to anyone seeking to familiarize himself with the alarmists’ efforts to squelch freedom and technology.

![[TEST] The Objective Standard](https://test.theobjectivestandard.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/logo.png)