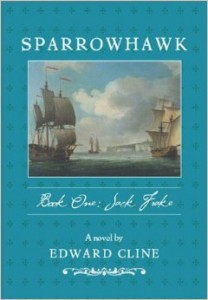

The Sparrowhawk Series, by Edward Cline. San Francisco: MacAdam/Cage Publishing (cloth).

Book One: Jack Frake (2001, 360 pp.)

Book Two: Hugh Kenrick (2002, 425 pp.)

Book Three: Caxton (2004, 223 pp.)

Book Four: Empire (2004, 290 pp.)

Book Five: Revolution (2005, 320 pp.)

Book Six: War (2006, 379 pp.)

The founding of the United States was among the most dramatic and glorious events in history. For the first time, a nation was founded on the principle of individual rights. Those interested in learning about America’s founding and its cause may turn to history texts. But history texts, even when their content is accurate, tend to be dry accounts of events. They lack the excitement of an adventure novel. Yet most novels set in the Revolutionary period are not good sources of information: Being works of fiction, they may take liberties with historical fact; and they often employ the American Revolution merely as their setting, not as their focus. What if one could find a work that combined the accuracy of a well-researched historical work with the dramatic presentation of a work of fiction? Fortunately, such a combination exists—the Sparrowhawk series of six novels by Edward Cline.

Cline’s purpose in this series is to dramatize America’s founding:

Most nations can claim a literature . . . that dramatizes the early histories of those countries. . . . But, except for a handful of novels that dramatize . . . specific periods of events in American colonial history, America has no such literature. The Sparrowhawk series of novels represents, in part, an ambitious attempt to help correct that deficiency (foreword to Book Three, p. ix).

The series is set in the decades preceding the Revolution, beginning in the 1740s in England and concluding in 1775 in colonial Virginia. Throughout, the books dramatize important events leading up to the war, such as the liberty-constraining acts of British Parliament against the colonies and the colonial response to them.

But Cline’s theme is that the fundamental cause of America’s declaration of independence from Great Britain was not mere events, but certain ideas Americans held. “[D]oing justice . . . to the founding of the United States . . . has meant understanding, in fundamentals, what moved the Founders to speak, write, and act as they did. Those fundamentals were ideas” (foreword to Book Three, p. ix). According to Cline, these fundamental ideas led inexorably to the Revolution: “The juggernaut of Parliamentary supremacy collided with the American colonies’ incorruptible sense of liberty, which could be neither crushed nor flung aside. The result was a spectacular explosion: the American Revolution” (foreword to Book Six, p. 1).

To dramatize his theme, Cline employs two fictional heroes “who reflect the moral and intellectual stature of the men who made this country possible” (foreword to Book Three, p. x). Jack Frake and Hugh Kenrick are English-born colonists from the bottom and the top of the British social ladder, respectively, both of whom “would not allow their claim to unabridged liberty to be corrupted” (foreword to Book Six, p. 1). Books One and Two trace each hero’s beginnings in England; each young man’s independent mind and unwillingness to submit to tyranny place him in direct conflict with British society. Book One spans the years 1744–1748 and follows Jack Frake’s development in Cornwall, England. Book Two picks up in 1749 and follows Hugh Kenrick for the next ten years. These first two novels are the best literarily and have the most exciting plots of the series. (When I read Book One for the first time, I stayed up all night: I simply could not put it down.)

The remainder of the series takes place in the American colonies, primarily in Virginia. So as not to ruin the excitement of Cline’s plot for those who have not read these novels, I will confine the rest of my summary to their historical context. Book Three picks up in 1759 with the French surrender of Canada to the British, which ensured British dominance in North America. The novel illustrates life in colonial Virginia and ends with King George III’s proclamation of October 7, 1763, prohibiting colonial settlement west of the Appalachians, thus penning in the colonials so he could better regulate and tax them.

Book Four begins in early 1764 with the Americans’ reaction to the proclamation. Parliament then passed several more acts injurious to the colonies. Among them was the Currency Act of April 1764, which abolished and prohibited payment of debts to British creditors in colonial paper, requiring all payment to be in hard money (coin). This impoverished and ruined many colonists. And in March of 1765, Parliament passed the infamous Stamp Act, which placed a tax on virtually all legal and trade instruments, even on newspapers and pamphlets. The novel traces the colonial reaction to these encroachments on their liberties, such as the drafting of the Virginia Resolves in May of 1765. The novel stresses the colonists’ objections to such acts on principle, not merely because these taxes would make it difficult for many colonial merchants to stay in business: The colonists recognized that such acts violated their rights, and, if tolerated, would open the door to further violations.

Book Five begins in June 1765 with the colonial boycott of the Stamps, which was well-organized and lasted for years. As a consequence of the boycott, Parliament repealed the Stamp Act in March of 1774. However, on that same day it passed the Declaratory Act, which reaffirmed Parliamentary legislative authority over the colonies “in all cases whatsoever.” The colonists rightly saw it as an even more ominous sign.

Conflict with Britain comes to a head in Book Six, which opens in the spring of 1774. In March, Parliament passed the first of its “Intolerable Acts”—closing Boston’s port until damages for the tea destroyed in the Boston Tea Party had been paid. A series of other Intolerable Acts and prohibitions follow, tightening the noose around the colonies. Skirmishes between colonists and British military units stationed in the colonies led to the Battle of Bunker Hill in Massachusetts in June 1775, which Book Six presents dramatically. The series ends with the onset of the Revolutionary War in the fall of 1775.

The series possesses a few relatively minor flaws. The plot action and historical facts are not always a unified whole: In Books Three through Five,Cline alternates stretches of plot with historical essays, which breaks up the story. Occasional anticlimaxes result from a failure to dramatize important events. For instance, Peyton Randolph, one of the founders, was originally a Tory. Although Cline stresses Randolph’s initial obstruction of the Patriots’ push for independence from Britain, his reversal is left unexplained; it is merely stated in two narrative sentences (Book Six, pp. 116–17).

In a number of moving scenes, the Sparrowhawk series illustrates the grandeur of America’s founding. Cline treats us to the sight of great men staking their lives, fortunes, and sacred honor on a principle—and winning. He also shows the consequences of bad choices. For instance, we follow a British military officer who is fully sympathetic to colonial complaints against Britain and defends a colonial family in a skirmish with a British agent, yet is unwilling to take sides and resign his commission. Cline dramatizes how this man’s failure to think through the issue costs him his life.

At the end of Book Six, one of the heroes invites a British boy to join his regiment: “Would you like to see a new country born, Tom? Stay with us, and you’ll see how it’s done” (p. 371). That sense of hope and the sight of value-oriented men fighting for great things permeate the Sparrowhawk series and make it very much worth reading.

![[TEST] The Objective Standard](https://test.theobjectivestandard.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/logo.png)