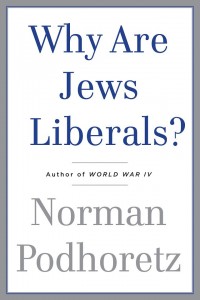

Why Are Jews Liberals? by Norman Podhoretz. New York: Doubleday, 2009. 337 pp. $27 (cloth).

Norman Podhoretz, Jewish neoconservative and former editor-in-chief of Commentary magazine, attempts in his book Why Are Jews Liberals? to answer the perplexing commitment of American Jews to modern liberalism. Jews, according to Podhoretz, violate “commonplace assumptions” about political behavior, such as that “people tend to vote their pocket books”; they “take pride . . . in their refusal to put self-interest . . . above the demands of ‘social justice’”; and they have consistently sided with the left in the “culture war” (pp. 2–3). According to statistics cited by Podhoretz, 74 percent of Jews support increased government spending and, since 1928, on average, 75 percent have voted for candidates of the Democratic Party.

Such political behavior “finds no warrant either in the Jewish religion or in the socioeconomic condition of the American Jewish community” (p. 3), argues Podhoretz; it can be explained only by realizing that Jews are treating liberalism as a “religion . . . obdurately resistant to facts that undermine its claims and promises” (p. 283).

Podhoretz traces the prevalent political orientation of present-day Jews to conditions suffered by their Jewish ancestors in medieval Europe and later in the United States. During the Dark and Middle Ages, Christian authorities in Europe placed severe restrictions on Jews, including where they could live and what professions they could practice. In later centuries, as the influence of Christianity declined, liberal revolutions swept much of the European continent, and, in the 19th century, Western European governments began recognizing the rights of Jews and treating them as equal under the law (p. 57). Even so, conservative Christians, who still supported the monarchies, remained opposed to the “emancipation” of the Jews (pp. 55–57). Consequently, Jews entered politics in Europe almost exclusively as liberals, in opposition to the Christian right that had oppressed them and their ancestors (pp. 58–59).

Governments in Eastern Europe and Russia, however, continued to persecute Jews well into the early 20th century (pp. 65–67), and, between 1881 and 1924, two million Jews immigrated to America, where they would be treated equally before the law. Most were poor, and few ventured out of Lower East Side Manhattan, where the majority found jobs in the textile industry, working more than sixty hours a week for low wages, and where even “modest improvements in their condition” were achieved only by the efforts of a Jewish labor movement (pp. 99–100).

According to Podhoretz, the initial leadership of the Jewish labor movement in early 20th-century America consisted of Marxist Jews “who had brought their ideological convictions from Russia to America” (p. 100). To them, “labor unions were a weapon in a war whose ultimate objective was the overthrow of capitalism,” and they “regarded collective bargaining as a form of collaboration with the enemy” (p. 100).

Although the Marxist Jews lost out to the moderate socialist Jews who were willing to negotiate with the capitalists to improve their lot, the union leaders “continued preaching the socialist gospel with scarcely diminished fervor” (p. 101). During the 1930s, despite criticism from the more radical communists, union leaders endorsed FDR’s New Deal, as it promised to “strengthen the hand of the unions” and “included a number of welfare measures that they, as socialists, had long been advocating” (p. 122).

Christian intellectuals in America, says Podhoretz, began to resent the new immigrants, and the number of anti-Semitic American Christian organizations increased from five to twelve hundred (p. 121). Representative of this group was the Christian Front, led by the Rev. Charles E. Coughlin, who praised Mussolini’s fascist regime and supported “Hitler’s war against ‘world Jewish domination’” (p. 121). Jews watching these developments (as well as extensive private discrimination against them in various industries and colleges) believed fascism was coming to America (p. 121). FDR, a strong supporter of the frequently Jewish-led labor movement, and hence a target of these anti-Semitic groups, received upward of 80 percent of the Jewish vote and even more when he joined the fight against the Nazis (pp. 123–24).

In the 1950s and through most of the 1960s, explains Podhoretz, anti-Semitism in American society virtually disappeared, as the political right sought to purge its ranks of anti-Semites. Even the John Birch Society expelled members “who were unable to restrain their frisky anti-Semitic passions . . . in public” (p. 155).

Soon, however, anti-Semitism sprang up on the left. For instance, in the late 1960s, in response to a New York Teachers Union strike protesting the promotion of a group of black teachers who “lacked seniority under the rules of contract between the . . . NYTU and the city” (p. 161), leftist black radicals became enraged and read the following poem over the radio:

Hey Jew boy, with that yarmulke on your head,

You pale-face Jew boy—I wish you were dead;

I can see you, Jew boy—you can’t hide,

I got a scoop on you—yeh, you gonna die.

In the mind of these radicals, Podhoretz observes, “all that mattered was that many of [the union’s] members were Jewish,” and “the strike was nothing more and nothing less than a struggle for power between blacks and Jews” (pp. 161–62).

Another factor fueling anti-Semitism in America, says Podhoretz, was Zionism, a movement “backing the existence of a sovereign Jewish State.” After the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948, Zionism became such an important issue for Jews that by the late 1970s, according to Podhoretz, 99 percent of American Jews were Zionists (p. 183). The American left, however, largely opposed Zionism. Following the Six-Day War of 1967—in which Israel conquered the Sinai Peninsula, the Gaza Strip, the Golan Heights, and the West Bank of Jordan, including Jerusalem; and after which Israel became a major recipient of American military aid—the left unified against Zionism, a unification that served “to legitimize the open expression of a good deal of anti-Semitism” (p. 161).

Podhoretz discusses a number of instances of anti-Semitism in the guise of anti-Zionism, including an article by Gore Vidal published in the leftist magazine The Nation. Vidal described Israel “as a

‘predatory’ nation ‘busy stealing other people’s land in the name of alien theocracy’” (p. 205). According to Podhoretz, Vidal’s article implied “that Jews—even those born in the United States!—were all foreigners living here by the gracious suffering of the natives” and that “they exercised enormous malevolent power over the politics of . . . ‘the host country’” (p. 205). Even the liberal Village Voice referred to Vidal’s piece as an “anti-Semitic screed” (p. 207). But few others on the left condemned it or saw anything wrong with it. By contrast, recounts Podhoretz, when conservative William F. Buckley was challenged on the anti-Semitism of conservative intellectual Joseph Sobran, Buckley proceeded to officially disassociate his magazine, National Review, from Sobran.

Nonetheless, notes Podhoretz, despite these and other examples of leftist hostility to Jews and Israel—and despite the absence of any significant anti-Semitism on the right—American Jewish support for liberalism has persisted: Jews have continued to support liberal causes and to vote for the Democrats in overwhelming majorities.

What explains this?

Although the historical experiences of the Jews with Christian anti-Semitism in Europe and the United States before World War II may account for the original liberalism of American Jews, argues Podhoretz, these factors fail to explain their continuing liberalism in the face of increased anti-Semitism on the left and decreased anti-Semitism on the right (pp. 269–70). Podhoretz also dismisses any deep commonality between liberalism and traditional Jewish values, arguing that the precepts of traditional Judaism have little in common with modern liberal policy prescriptions (pp. 277–79) and pointing to the relative conservatism of Orthodox Jews, who are deeply religious yet not as committed to liberal causes and candidates as their non-Orthodox brethren (p. 277).

The source of the persistence of Jewish liberalism, says Podhoretz, derives from the nature of the original choice facing Jews upon their emancipation in Europe. Most of these Jews attempted to continue practicing traditional Judaism while simultaneously becoming normal citizens of their countries of residence—countries in which the vast majority of people were Christian. Podhoretz points out that, over time, in the face of continuing anti-Semitism, many Jews abandoned this effort and simply converted to Christianity (pp. 47–48). Others—especially Jewish intellectuals—sought an alternative in the form of a doctrine advocating “a world in which the distinction between Jew and Gentile would become irrelevant and therefore erased” (p. 63). According to Podhoretz, Marxism was the doctrine these Jews embraced toward that end.

“[The] embrace of Marxism [by many emancipated Jews] had the feel and the force not of an abandonment of Judaism in favor of a wholly secular philosophy, but rather of a conversion from Judaism to another religion” (p. 63). Podhoretz notes a similarity in the fantastic beliefs of traditional Judaism and the fantastic beliefs of Marxism:

In spite of all the persecution they endured, the Jews of premodern times never stopped believing that they were God’s chosen people; and in spite of the seemingly irrefutable case that could be made against His promise . . . they continued to proclaim . . . I trust in Him. . . . The belief of the Jewish Marxists in the glorious promise of socialism was commensurately resistant to refutation by the horrors of “actually existing socialism” in the Soviet Union and other countries living under Communism (pp. 280–81).

But the bloody nightmare of socialism in practice was too much to evade for long, especially when capitalism was producing “a level of prosperity for the poor that surpassed even the rosiest utopian dreams of Marxist theory” (p. 282). So the Marxist Jews mitigated their Marxism and became advocates of “social democracy” and, later, of American liberalism, which conveniently “had been steadily moving to the left and was looking more and more like European socialism and less and less like the American liberalism of an earlier day” (p. 282). The result of this trend, says Podhoretz, is that today,

To most American Jews . . . liberalism is . . . the very essence of being a Jew. . . . it is a religion in its own right, complete with its own catechism and its own dogmas and, Tertullian-like, obdurately resistant to facts. . . .

[F]or most American Jews, ethnic “Jewishness takes precedence over Judaism.” But insofar as these ethnic Jews pay any mind to Judaism at all, they regard it as, in “essence,” liberalism by another name. Hence in their eyes being “a liberal on political and economic issues” is equivalent to being “a good Jew” (pp. 283–90).

In further support of his thesis, Podhoretz points out that some liberal Jews, such as Michael Lerner (editor of the leftist Jewish magazine Tikkun), explicitly “defend the liberal faith by claiming that it is indeed the new ‘Torah’ of the Jews” (p. 287).

Podhoretz argues that his theory of liberalism as the new Jewish religion not only explains why Jews are liberals, but also explains why Jews stubbornly refuse to recognize anti-Semitism on the left: Because they equate Judaism and liberalism, they regard anti-Semitic “liberals” as by that fact not liberals—on the grounds that true liberals could not possibly hold such views (pp. 285–86).

Although Podhoretz certainly identifies some causal factors in the realms of history and politics, he flatly denies the fundamental philosophic factor contributing to the liberalism of Jews: the liberal ideas within the Jewish religion. He even explicitly dismisses Jewish liberals who correctly point out that liberalism “goes to the heart of our religious and historic heritage” and that Judaism “compels us to be concerned with the unfortunate and the stranger in our midst” [emphasis in original] (p. 276). Accordingly, Podhoretz fails to sufficiently answer the question posed in the title of his book.

Apart from this rather substantial flaw, however, Why Are Jews Liberal? does shed some light on the historical and political causes of liberalism among Jews, and anyone interested in this subject will profit from reading it.

![[TEST] The Objective Standard](https://test.theobjectivestandard.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/logo.png)