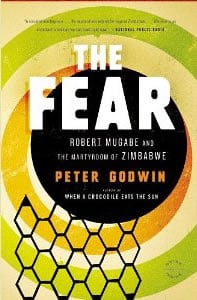

The Fear: Robert Mugabe and the Martyrdom of Zimbabwe, by Peter Godwin. New York: Little, Brown and Company, 2011. 384 pp. $26.99 (hardcover).

Many books have documented horrible details of what happens under dictatorship. The Fear: Robert Mugabe and the Martyrdom of Zimbabwe presents some of the most horrific. In it, Peter Godwin captures the recent and ongoing struggle of Zimbabweans under a reign of lawlessness and terror.

The book begins in 2008, as Godwin is on his way “home to Zimbabwe, to dance on Robert Mugabe’s grave” (p. 5). Despite rigging the latest elections and intimidating the voters, as he has for many years, the aging dictator has been rejected so resoundingly that it seems he will have to accept defeat.

After flying into Harare, the capital of this formerly rich and now starving country, Godwin says that “[Mugabe’s] portrait is everywhere still, staring balefully down at us.”

From the walls of the airport, as the immigration officer harvests my U.S. dollars, sweeping them across his worn wooden counter, and softly thumping a smudged blue visa into my passport. From the campaign placards pasted to the posts of the broken street lights, during our bumpy ride into the reproachfully silent city. Watched only by the feral packs of hollow-chested dogs, [Mugabe] raises his fist into the sultry dome of night, as though blaming the fates for his mutinous subjects. The Fist of Empowerment, his caption fleetingly promises our insect-flecked beams. (pp. 5-6)

As Godwin makes his way into Harare, pickup trucks crowded with armed officers repeatedly pass him by. “The atmosphere,” he says, “is tense with anticipation” (p. 8). Something historic is about to happen. Unfortunately, however, Mugabe does not concede defeat, and there is “no political grave upon which to dance”—at least not one belonging to Mugabe (p. 14). But there will be many graves soon, an untold number of them, as Mugabe and his goons “know the places they didn’t do well” and plan to ensure they do better by terrorizing the local populace into changing their votes (p. 28).

Godwin skillfully shows what led up to the impending massacre. According to him, there was no single point at which Mugabe the “liberation hero” became Mugabe the “tyrannical villain.” And that, says Godwin, is because there was no metamorphosis: “Robert Mugabe has been surprisingly consistent in his modus operandi. His reaction to opposition has invariably been a violent one” (p. 30).

Referencing the massacre of around twenty thousand civilians in Matabeleland soon after Mugabe first gained power, Godwin goes on to describe the nature and purpose of the latest postelection terror:

[T]he murders are accompanied by torture and rape on an industrial scale, committed on a catch-and-release basis. When those who survive, terribly injured, limp home, or are carried or pushed in wheelbarrows, or on the backs of pickup trucks, they act like human billboards, advertising the appalling consequences of opposition to the tyranny, bearing their gruesome political stigmata. And in their home communities, their return causes ripples of anxiety to spread. The people have given this time of violence and suffering its own name, which I hear for the first time tonight. They are calling it chidudu. It means, simply, “The Fear.” (p. 109)

Although the name is new, Godwin points out that nothing has changed and that fear has always been the base upon which Mugabe’s power has rested. If that truth does not always seem real to Zimbabweans, it is—at least according to Godwin—in part because of how so many have chosen to deal with it. In this dictatorship, he says, people use subversive nicknames to mollify the nature of what exists.

When we mention Mugabe’s draconian spying agency, the Central Intelligence Operation (CIO), we often call it Charlie Ten. And instead of referring to Robert Mugabe by any of his many official titles—His Excellency, Supreme Leader of ZANU-PF, Commander in Chief, Comrade—most Zimbabweans call him, simply, Bob. After all, how can you be scared of a dictator called Bob? (p. 12)

As Godwin travels across the country, the full nature of what exists, and the answer to that last question, becomes clear. Godwin relates how Mugabe’s generals launched Operation Mayhoterapapi—i.e., Operation “Who Did You Vote For?”—and tells what happened if they suspected someone of voting for the opposition party, MDC. He becomes, as he puts it, a “stenographer to their suffering” (p. 138).

Godwin reports that Mugabe’s men would show up with sticks and bayonets, and then say to their victims, “You have sold your [vote] to the opposition and now you will pay for it” (p. 105). He goes on to show the various gruesome ways those people did pay, and, if you have never had nightmares, chances are you will after reading The Fear, so horrible are the details.

Consider the story of a woman who left one of her year-old twin boys at home in order to run errands.

When she returned, she found her husband dead on the floor next to her son, who had been decapitated. The Mugabe thugs who had done this then grabbed her and gang-raped her next to her headless baby and her husband’s corpse, while her other baby sat crying nearby. (p. 199)

There is nothing to do after such stories except pause and try to breathe. They appear repeatedly throughout The Fear, and they stay in your gut like concrete, holding down and muffling the screams of terror that you feel but cannot release.

Godwin’s manner of vividly capturing what this tyranny does to its victims is the book’s paramount value. Whereas other books may focus on the morbid statistics of lawlessness and tyranny—or the evil ideas that underlie such states—The Fear provides unforgettable images of what those statistics mean, of what the ideas lead to. According to Godwin, it is by design:

I shrink from generalizing what “they” have gone through, because it can feed into that sense that this is some un-differentiated, amorphous mass of Third World peasantry. Some generic, fungible frieze of suffering. One that animates briefly as you intersect with it, rubber-necking at it, a drive-by misery that disappears as you motor away over the horizon. (p. 138)

Thankfully, just as Godwin makes otherwise forgettable statistics vividly memorable, he does the same for the admirable courage that many Zimbabweans have shown in response to the war unleashed upon them.

Despite being forced to chant themselves hoarse in praise of Mugabe, having their houses burned, their crops stolen, and their children or parents murdered, they fight on. They are thrown in jail, where they room with the dead, where they are beaten, electrocuted, and starved. Still, they fight on. As a single example, consider the story Godwin shares of Chenjerai Mangezo, an MDC candidate who was elected to a spot on the local council.

Shortly [after the election], deep into a starless night, a large posse of Mugabe’s men surrounded [his] small house. “We have come to kill you,” they chanted, and rained large rocks down upon the roof, preparing to burn it down.

Realizing that his wife and daughter were likely to be killed too, he ordered them under the beds. Then he burst out of the house, yelling and generally attracting the attention of his predators as he blundered down the hill, away from the house, hoping they would all pursue him, which they did, swarming after him, throwing rocks and spears, until finally one blade felled him, piercing his leg.

And as he lay on the ground, they loomed over him and smashed rocks down upon him, and they beat him with logs, lifting them high to get in good meaty bone-breaking blows, and he knew then that this was what it was like to be killed. He could feel his legs being broken, his arms splintering, his skull gashed and the taste of his own blood as it flowed down over his eyes into his mouth.

Lying here among the fresh green stalks of maize that he had planted but would now not live to eat, he uncurled his arms from where they had been protecting his head, and he managed to hoist himself up a little so that he could look at his assailants, now lit against the newly emerging moon. And he said to them, “You had better be sure to kill me. Because if you don’t, I am going to come after you, all of you. I know who you are.” (p. 352)

Godwin continues the story, telling how Chenjerai’s life was ultimately saved by how far he was able to run away from his house—the place where the hit squad had been ordered to kill him. Godwin also shares how “the first thing [Chenjerai] did [upon regaining consciousness in the hospital] was to get all his mates to write MDC slogans all over his plaster casts.” Later on, Chenjerai shows up for his swearing-in ceremony beaten up, unable to walk, but with his head unbowed (p. 353).

The courage of Zimbabweans such as Chenjerai has unfortunately not been enough to overthrow Mugabe’s regime. In fact, Godwin relays near the book’s end that their efforts have ended in a “unity government” with Mugabe. Here, they are charged with paying for “the bullets that were used against [them] in the last elections” and prevented from doing anything that might benefit the people they represent (p. 321).

Although Godwin and many of those he quotes see this new government as unstable and unlikely to eliminate the need for violent overthrow, The Fear does end on a hopeful note. Mugabe’s men have started beating up each other “for not showing enough loyalty”—possibly a sign of division within the ranks—and those opposed to Mugabe’s tyranny have not given up on justice. They are, says Godwin, working and waiting for it. Anyone who reads The Fear will certainly hope for justice sooner than later.

[/groups_can]

![[TEST] The Objective Standard](https://test.theobjectivestandard.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/logo.png)