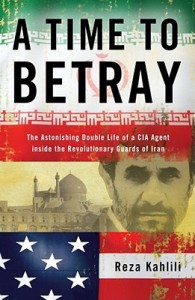

A Time to Betray: The Astonishing Double Life of a CIA Agent Inside the Revolutionary Guards of Iran, by Reza Kahlili. New York: Threshold Editions, 2010. 352 pp. $26 (hardcover).

At the start of A Time to Betray, Reza Kahlili writes that this is “a true story of my life as a CIA agent in the Revolutionary Guards of Iran.” As such, you might expect it to be a fast-paced thriller—and, if so, you’d be partially correct. A Time to Betray involves many intense moments, but its primary focus is on the choices that Kahlili and his two childhood friends made growing up in Iran, along with the sometimes-deadly consequences.

One of those friends, Kazem, always took religion seriously, hated the Shah, and, when the Shah was overthrown, became a supporter of Khomeini and a devoted member of the Intelligence Unit of the Revolutionary Guards.

Soon after the Shah’s overthrow, Kazem asked Kahlili to join the Guards. Having just returned from studying in the United States and being eager to help improve his country, Kahlili joined. Looking back today, he explains that, like many Iranians, he naïvely believed Khomeini and the mullahs would keep their promise not to force their faith on Iranians.

Kahlili’s other childhood friend, Naser, was not so naïve. Although he, too, was happy to see the Shah overthrown, Naser began speaking out against Khomeini soon after. He explained his reasons to Kahlili:

“Look around, Reza. Everything is changing. Banning the opposition parties, shutting down the universities, attacking whoever disagrees with them. They’re taking our rights away. They’re arresting innocent people for nothing more than reading a flyer.”

I tried to calm him down, attempting to soothe my own rattled nerves at the same time. “We’re in a transition, and change is always difficult. Maybe you should be more careful. Things will get better, you’ll see.”

Naser took a moment before speaking again. When he did, there was pain in his voice. “I wish I felt the same way, Reza. I don’t want to argue with you, but if people don’t speak up now, it will only get worse.” (p. 60)

Numerous times, we see the young Kahlili not wanting to take sides, simply wanting everyone, in spite of everything, to get along. Indeed, this approach appears to have been his MO from childhood. Kahlili writes that, as a child, he found it tough just to stand up to his mother and friends. How could he, as an adult, stand up to the government of Iran? Something compelling would have to happen—something that threatened or assaulted his values on a personal level. Unfortunately, something did.

The regime arrested Naser and took him to Evin Prison, where he was tortured and then repeatedly forced to watch his younger brother being beaten and his younger sister being raped. Hearing of where Naser was being detained, Kahlili used his good standing in the Guards to visit him there. Inside, Kahlili saw some of the atrocities only whispered about outside the prison walls, and he finally recognized the nature of the regime he was working for. From that moment, he felt intense guilt for his involvement in the Guards. And he became more curious; he wanted to know what even he, as a member of the Guards, was unauthorized to know about what went on in that prison.

He soon learned the full extent of the atrocities being committed in Evin from the suicide letter of a young woman who suffered them. At that point, Kahlili explains, he could “no longer remain quiet and watch [the] country disappear into a morass of evil.” But what could he do? Upon reflection, he realized:

I needed to go back to America, to the one other place I’d ever called home. America was one of the true superpowers in the world, and I was convinced that Americans didn’t really know what was happening inside of Iran—and that if they did, they would do what they could to come free us. Someone needed to tell them about the atrocities. (p. 97)

Using as an excuse a sick aunt and his duty to repay the help she had offered him when he had been in America studying, Kahlili, with the help of an oblivious Kazem, made it back to the States. There, Kahlili says, he shared with the CIA everything he knew about the Guards, expecting that to be that. But the CIA asked Kahlili if he would be willing to work for them, as a spy embedded in the Guards. Given the obvious and profound danger involved, Kahlili was reluctant, but wanting desperately to save his country from the evil regime, he agreed. His training began immediately, and he was soon back in Iran, undercover.

Kahlili recounts various missions and events, sharing his thoughts and fears along the way. He also conveys what this decision meant for his relationships with family and friends. For example, he relates how his grandfather hated the clerics, in particular their attempt to force their religion and way of practicing it onto others. He quotes his mother calling those who supported them “donkeys,” “jackals,” “traitors,” and “imbeciles” (p. 64). And he shows how his continued involvement with the Guards repeatedly threatened to end his marriage.

The same Kahlili whom many referred to as a coward now faced the certainty of torture and death if he were exposed as a spy and the damnation of those he loved so long as he continued working for the Guards.

Unfortunately, despite Kahlili’s efforts, America was doing little with the information he provided them, instead responding to new threats with ever more appeasement. As a result, Kahlili became increasingly disheartened and began questioning whether he should continue working for the CIA. In one passage, he writes:

I had been risking my life to rid my country of the criminals running it and the Americans were negotiating with them. The CIA knew that the Guards were responsible for the barracks bombing in Lebanon that took the lives of 241 American servicemen. They knew that their own people, William Buckley, were being kidnapped, tortured, and killed. Yet they were offering appeasement to these two-faced donkey-riding mullahs. (pp. 250–51)

After much deliberation, Kahlili decided both to leave the Guards and quit working for the CIA. To discover how he managed to implement these decisions, you’ll have to read the book, which I highly recommend.

A Time to Betray delivers much more than inside information about the ever-growing Iranian threat and the corresponding evasions of the U.S. government. The primary value of the book is that it tells a true story of a man of remarkable courage, the kind of man we desperately need more of today.

![[TEST] The Objective Standard](https://test.theobjectivestandard.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/logo.png)