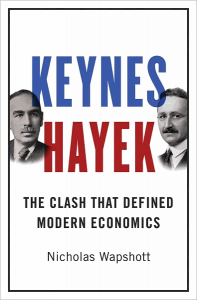

Keynes Hayek: The Clash That Defined Modern Economics, by Nicholas Wapshott. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2011. 382 pp. $28.95 (hardcover).

The financial-economic crash of 2008–9, dubbed the “Great Recession” by pundits who have insisted its severity was second only to that of the Great Depression (1930s), has been blamed on “greed,” tax-rate cuts (2003), the GOP, and looser regulations in the prior decade—that is, to what passes today for full, laissez-faire capitalism (the same culprit fingered in the 1930s). The crash has also renewed interest in Keynesian economics, which holds that free markets are prone to failures, breakdowns, and recessions due to excessive production (supply) and can be cured of slumps only by state intervention to boost demand and dictate investment. And the crash has led to the worldwide adoption of two pet policies of John Maynard Keynes (1883–1946): massive deficit spending and inflation to “stimulate” stagnant economies. In fact, economies continue to languish not in spite of Keynesian policies but because of them.

One key factor precipitating the recent revival of Keynes was the awarding of a Nobel prize to Keynesian Paul Krugman in fall 2008, during the worst weeks of the crisis, when the $700 billion bank bailout (TARP) was debated and enacted. A half dozen new books since 2008 also have helped revive Keynesian notions; one is subtitled “return of the master,” another eagerly reports that the crash has “restored Keynes, the capitalist revolutionary, to prominence.” As in the 1930s, when Keynes first exerted strong influence on policy, he is depicted today as capitalism’s savior, favoring a mixed economy to quell popular angst of recessions and prevent more authoritarian alternatives (fascism, communism).

Like most intellectuals today, British journalist Nicholas Wapshott (formerly senior editor at the London Times and New York Sun) falsely attributes the recent financial crisis to overly free markets; he also admires Keynes, his demand-side theories, and his interventionist policies. Yet unlike typical hagiography on Keynes, Wapshott adopts an ideas-oriented approach to Keynes’s revival in his book, Keynes Hayek: The Clash That Defined Modern Economics.

Like most interpreters, Wapshott believes that Keynesianism somehow “saves” capitalism from itself and from ultimate political tyranny, although he does not deny (or bother to hide) the many cases where Keynes expresses an unvarnished hatred for individualism and free markets. He acknowledges (and welcomes) the return of Keynesian policies, but he worries they may have been hastily implemented and thus ineffectual, given that multi-trillion-dollar stimulus schemes in the three years since 2008 have not boosted growth or jobs. Wapshott rightly recounts how Keynesianism was discredited during the 1970s “stagflation” (which it could not explain) and successfully challenged by “efficient market” theorists and classically oriented supply-siders (“Reaganomics”). But he exaggerates the reach of pro-capitalist ideas and policies in recent decades, and pins blame for the recent crash on what is still free about markets, not on the state interventions that necessarily render otherwise efficient markets dysfunctional and destructive.

Yet Wapshott’s main goal in Keynes Hayek is to have us understand Keynes’s recent revival in the context of a long-running battle or “clash” between the ideas and policies of Keynes and those of Austrian economist Friedrich Hayek (1899–1992), who is portrayed as the champion of free markets and skeptic toward state intervention. Wapshott mostly succeeds in achieving his goal, but in the end he draws the wrong conclusion—namely, that the Keynesian revival is warranted—because he believes, not merely with Keynes, but, we see, also with Hayek, that markets fail when left free. In fact, free markets do not fail, but widespread belief that they do has helped revive Keynes.

Wapshott tries to portray Keynes and Hayek as near black-and-white opposites, in both theory and policy. Keynes he paints as the practical “idealist” who recognizes that free markets are prone to fail and that recessions are unjust to the poor, yet remains optimistic that central planners can know how to fix the failure and will do so. Hayek he describes as the “pure theorist” who, in his early years, denies that free markets fail (a view he abandons later) and doubts central planners have the knowledge or incentive to fix the alleged failures. In reality, their differences are not nearly as sharp as Wapshott paints them to be.

Wapshott does not explicitly identify the fundamental similarities underlying Keynes and Hayek’s ideas. Fortunately, his thoroughness and candor in portraying the economic debates between the two men (and their followers) since the 1930s enables a careful reader to readily discern, contrary to the conventional interpretation, that Keynes and Hayek agreed about more principles and policies than they disagreed about. Likewise, he shows that neither of them advocated genuine, laissez-faire capitalism—that is, free markets with a government limited to the preservation of individual rights by the rule of law.

Consequently, Wapshott’s subtitle—“the clash that defined modern economics”—is unwittingly accurate, because economics today, as taught in the universities and practiced by all policy-makers, allows no room for genuine capitalism, and thus embraces the mixed economy, in some degree or another, just as Keynes and Hayek did. Wapshott believes modern economics is bifurcated between interventionist Keynesians and anti-interventionist Hayekians. In fact it entails two (or more) versions of the mixed economy, each endorsed to varying degrees by followers of Keynes and Hayek alike. From Wapshott’s fairly accurate account of Hayek’s views and anticapitalist concessions, it is obvious that Hayek was far from being a champion of laissez-faire capitalism. And Wapshott doesn’t hesitant to expose this—even at the cost of backpedaling on his early, overly strong claim about an alleged “clash” of opposites between Keynes and Hayek—because it makes it easier for him to portray the Keynesian case as unassailable and the recent revival of Keynes as warranted.

In documenting his case, Wapshott effectively devotes alternating chapters to Keynes and then Hayek throughout the book. He begins with Keynes in the 1920s becoming famous when he denounces the post-WWI Treaty of Versailles as imposing excessively harsh terms and reparations on the war’s perpetrators (Germany and the Central Powers), claiming it will destroy Europe and counseling debt payment moratoriums and defaults, and the abandonment of the gold standard. In the mid-1920s, Keynes pens a screed against capitalism and the moneymaking motive titled “The End of Laissez-Faire.” A young Hayek joins the debate in 1930 with what Wapshott calls the beginning of a battle, a mild review of a book by Keynes on money with which Hayek mostly agrees. Hayek does, however, complain that Keynes is unfamiliar with Austrian capital theory. Keynes responds petulantly and dismissively, and mostly ignores Hayek until the mid-1940s, when he reads the latter’s Road to Serfdom (1944). Keynes half-praises it to Hayek but questions its main theme: that mixed economies invariably devolve into fascistic or socialistic tyrannies. No, Keynes says; the well intentioned will make sure the mixed economy stays mixed. (Hayek also says he cannot decide whether the road to serfdom is an express lane or has off-ramps.)

For the years 1930–43, Wapshott seems to overstate the extent of the interaction between Keynes and Hayek, and surely exaggerates their theoretical differences. In the middle of this period—the deepest depth of the Great Depression—Keynes publishes his most famous book, The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (1936). It rejects classical, free-market economics and policies in favor of vast intervention by government—deficit spending, public works projects, inflation, war—to cure the slump.

Wapshott addresses the long-standing mystery about why Hayek never bothered to critically review Keynes’s book, which rapidly became prominent. Various possible explanations are offered, including those given (in retrospect) by Hayek himself. But none of them seems to make sense. Whatever the reason, Wapshott shows that Hayek was effectively AWOL on economics and policy advice during the all-important battle in the 1930s about whether capitalism or socialism was the genuine cause (or likely cure) of the Great Depression. Keynes “won” by default.

Wapshott shows how Keynes’s anticapitalist views, albeit partly accepted in the 1920s, soon swept the Anglo-American world in the 1930s, especially at Cambridge (UK) and Harvard, and among policy-makers. Eventually millions of students worldwide were instilled with Keynesian-induced doubts about free markets and faith in central planning, beginning with The General Theory (1936). Acceptance of Keynes’s ideas accelerated with the first edition of the widely adopted Keynesian textbook, deceptively titled Economics (1948), by a Harvard-trained professor at MIT, Paul Samuelson. The fifteen subsequent editions of his textbook monopolized economics training in both the United Kingdom and the United States until the 1990s. Pro-capitalist professors could find no equivalent textbook written from the perspective of Austrian economics. Wapshott does not sufficiently emphasize the undeniable trailing effect of this widespread Keynesian training on millions of people and how it (along with tenure) could make much easier a revival of Keynesianism in 2008 after only a couple of decades of its seeming retreat, both in academia and in politics.

Wapshott shares with most other followers of the Keynes-Hayek “debate” a curiosity about why, in the end, and even despite the collapse of the USSR and most of the world’s socialist regimes in the 1990s, Hayek nevertheless “lost” the debate. In terms of intellectual acceptance and political application, that is an accurate verdict, especially when we see how much Keynesianism persists today. But what explains the verdict?

The main explanation, according to Wapshott, is that a practical world has come to recognize the truth of Keynesianism: that markets fail and that state intervention fixes its failures; that governments do not cause recessions or depressions but can, through deficit spending and money printing, get an economy out of them. It is not an answer that will prove convincing to free-market advocates, but it is Wapshott’s answer—and the answer most of today’s economic leaders give. In blaming the debacle of 2008–9 on pro-capitalists and free markets, Wapshott claims that Hayek’s ideas and policy advice dominated the prior three decades (1978–2008). This claim is false on its face, but even if it were true, why would officials in 2008 so quickly and fully adopt Keynes’s ideas and policies?

Wapshott gives other reasons why Hayek’s economics did not refute or surpass Keynes’s economics—including that Hayek failed to review Keynes’s book in 1936, that Hayek was too young versus Keynes, that in the Anglo-American world a thick German accent disadvantaged Hayek, and that those sympathetic to Hayek were tardy in translating his Austrian writings into English and thus lost an expanded readership. These, too, are unconvincing, superficial, and nonessential.

Wapshott further suggests that Hayek “lost” because he focused on microeconomics (the theory of the firm’s behavior and pricing), as against Keynes’s bigger-picture macroeconomics (that of employment and cycles). Yet the same year that Keynes’s General Theory appeared (1936), so did the English-language version of Hayek’s highly relevant 1929 book, Monetary Theory and the Trade Cycle,which was also on macroeconomics and directly relevant to the Great Depression. Yet while Keynes’s book was widely praised and actively deployed, Hayek’s book was largely ignored.

Perhaps Wapshott’s best guess as to why Keynes succeeded where Hayek failed is his pointing out that Keynes’s work dealt mostly with issues of practical policy-making, whereas Hayek’s entailed “pure theory” or abstruse arguments detached from reality. Hayek’s work was detached from real-world policy, hence devoid of the capacity to advise on ways to fix the wrecked economies of the 1930s. Indeed, Hayek believed government should do nothing, whether in a boom or a bust, to influence outcomes—even though pro-capitalist advice could and should include making the currency good as gold, cutting tax rates, curbing spending, reducing tariffs, and slashing regulation. The question in such circumstances should not be whether government should act, but whether it should act in anti- or pro-capitalist ways.

The only plausible explanation Wapshott gives for the brief revival of free-market economics in academia in the mid-1970s and in government policy-making, with the semi-free-market programs of Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan during the 1980s (and extending into the 1990s), is the arrival of that rare combination of a high inflation rate and high jobless rate in the 1970s (“stagflation”), which Keynesian economics denied was possible, could not explain, and did not redress. In contrast, supply-side and monetarist policies stopped stagflation immediately. Wapshott also cites awards of the Nobel Prize to Hayek in 1974 and Milton Friedman in 1976, which bestowed respect and attention on free-market views.

Yet none of Wapshott’s supposed explanations of the success of Keynes’s economics over Hayek’s—with “success” defined as the extent of its acceptance in academia, business, and policy-making—are convincing, because they don’t go deep enough. A more accurate and convincing answer comes when we move beyond the claim of a huge “clash” between Keynes and Hayek and acknowledge that the theoretical-moral differences between them are not great: that Keynes “won” tactically because he was more consistent in his case for the interventions that Hayek only partly endorsed, and philosophically because the moral-political context of the past century, dominated as it was by altruism and fascistic-socialist regimes, favored Keynes. When self-sacrifice and subordination of the individual to the state are praised as virtuous acts, Keynes’s statist prescriptions appear perfectly apt.

Wapshott is unaware that moral philosophy sets the conditions for what is popular and politically feasible. The fact is, if altruism is prized, politics will be statist, and interventionist (Keynesian) economists will be in high demand; if instead egoism is prized, capitalism will be the political result, and free-market economists invariably will be sought for advice.

More than Hayek did (or wished to do), Keynes gave advocates and practitioners of big government and intensive intervention the policy schemes and plausible rationalizations for even bigger government and intervention, while politicians and the media told voters that it would create jobs and “get the country moving again.” Although Wapshott provides neither tactical nor philosophic explanations for why Keynes has “succeeded” where Hayek has failed, careful readers can find many examples in Wapshott’s own book.

In numerous places we read of Hayek’s deep “admiration” and “respect” for Keynes and his theories or policies, but few cases in reverse, with Keynes (or his followers) touting Hayek or Austrian economics. In his youth Hayek was a social democrat, as was Keynes all his life; both men believed in socialism as a moral ideal—and as a practical system, too, if it won a majority of the vote. Both men acknowledged that mass joblessness was due to excessively high real wages. But Hayek said the natural fix was a voluntarily negotiated lowering of nominal wage rates, whereas Keynes endorsed the coercive power of unions to keep nominal wages elevated and advised a deceptive erosion of real wages through inflation. Both endorsed the myth that markets are in constant “disequilibrium,” that they never “clear” properly (meaning demand and supply do not balance), with the result that surpluses and shortages persist. This frequently cited reason for intervention concedes to Keynes.

Both men also believed the money and credit system itself (not central banking per se) caused a “boom-bust” cycle, where investment exceeded saving during a boom and saving exceeded investment during a bust (in both cases, the market interest rate failed to balance them). Hayek said nothing could be done about it. But Keynes defended comprehensive state management of money and credit, a position statists eagerly welcomed in a century devoted to vast expansions in the welfare-warfare state. Both Keynes and Hayek opposed the gold standard and defended central banking, with fiat-paper money issuance—yet another concession to government intervention on the part of Hayek.

Finally, Hayek advocated a smaller, yet still rights-violating welfare state, partly in his Road to Serfdom (1944), then more expansively in The Constitution of Liberty (1961), including endorsements of redistributionist taxation, unemployment subsidies, welfare spending, trust-busting, regulation, and social security schemes.

Although Wapshott fails to dig deep enough to identify the moral and philosophic ideas at play in the thinking of both Keynes and Hayek, consequently claiming a bigger gap between their ideas than there really is, he does shed light on the fact that neither of these men was a true scientist or advocate of capitalism. He shows that both men believed that markets left free tend to “fail” and that both endorsed mixed economies (albeit with distinct mixes). Wapshott’s arguments would be much stronger, though, if he understood that Keynes and Hayek “define” modern economics, as he claims, not because they are opposites but because they share the moral premises that underlie the social democrats’ fantasies of the practicality of the welfare state.

![[TEST] The Objective Standard](https://test.theobjectivestandard.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/logo.png)