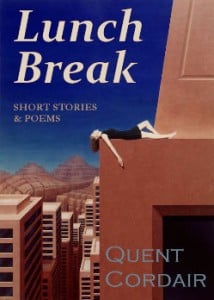

Lunch Break by Quent Cordair. Cordair Inc., 2012. 148 pp. $7.95 (Paperback); $3.95 (Kindle).

Around the middle of one of the short stories included in Lunch Break, Garret Brace, the hero of the story, walks into a room where one of his favorite childhood movies is playing.

The movie was about a woman whose mission it was to find a cunning enemy agent, to seduce him and kill him. There was little known about the man, not even his name. Armed only with a blurred photograph, a small handgun and her determination, she tracked and pursued him all over the world, always coming within just a few moments or a few steps of seeing him. As she learned his every habit and motivation, she became increasingly captivated, and driven as much by a need to see his face as by the necessity of completing her task. Finally, she followed him to a remote desert, certain that he wouldn’t be able to elude her there—but she became hopelessly lost. Overcome by exhaustion and the burning heat, she fell to the sand.

Lifting her eyes, she saw him on the crest of the dune above her, traced against the white desert sky. Pulling herself to her knees, she drew the gun and aimed . . . but her hands began to shake. She wiped a tear away with her sleeve.

“I’m sorry,” she said, “but you see—I’ve fallen in love with you. . . .” She steadied the gun, closed her eyes, and fired. (p. 17–18)

The description of this movie (the above is partial) is typical of “A Prelude to Pleasure,” the short story it came from, as well as the others in Lunch Break, a collection of short stories and poems by Quent Cordair.

Cordair, a painter as well as a writer, uses words as a painter uses paint. Here, for example, Cordair’s description of what the woman is armed with—“a blurred photograph, a small handgun and her determination”—serves as a sort of portraiture in action, selectively showing readers her character, deadly intentions, and conflict. Cordair’s descriptions of other characters and their actions are as extraordinarily selective and effective—whether showing their strengths, weaknesses, dilemmas, emotions, or any other elements. Consider his introduction of the hero in “A Prelude to Pleasure”:

Garret Brace was soaring seven miles above the earth, flying faster than sound. When the snowcapped Rockies came sharply into focus, he pulled the wheel back with one finger, pushed the throttle in with another and sent his plane climbing toward a wall of dark thunderclouds. The white machine sliced neatly through them and shot out into an empty blue sky, where below, there was only a carpet of cottony cumulus stretching away to the distant horizon. (p. 3)

This shows rather than tells readers what they need to know about Brace. They see that this is a man who can deal with the challenges of living and acting in this world.

It also indicates what readers can expect to find in abundance in the unique world of Quent Cordair’s short stories: stylistic romanticism—not naturalism. Cordair’s characters are in control of their lives, they choose their actions, and their choices drive the story.

Cordair describes the scenery, settings, landscapes, and cityscapes with the same attention to detail and selection of concrete images that you would expect from a painter who describes himself as a romantic realist. In “The Seduction of Santi Banesh,” for example, when the heroine, Santi, and her younger brother, Andjani, first see the city of San Francisco, Cordair paints their view:

They were rounding a turn in the freeway, cresting the top of a hill, and there before them lay the city, sweeping from west to east, across the hills and down to the bay. The vast, intricate spread of interconnected pinnacles, domes, parapets, grand halls and gardens was nothing less than a modern fairytale palace. Tufts of fog clung to the edge of the bay beneath a double-decked bridge which arched out and over to an island of green, only to leap away again into the eastern haze. The sunlight had gathered on a greenhouse roof atop a slender hilltop apartment tower, from where it was scattered in a sunburst through the lingering morning mists. The vision was wrapped in ribbons and bows of highway, one end of which swept out to them to flow beneath the wheels of the car. (p. 56)

Later, Cordair shows Santi walking through the malls and down the street, continuing to see one marvelous thing after another until she is giddy with wonder. At one point, she even notices “a handsome young father walk by with triplet boys in tow, all dressed in identical designer clothes” (p. 59).

Such scenes are enough to make a naturalist scream, “The world’s not like that!” The world of Cordair’s fiction, however, is.

This is not to say that Cordair’s characters don’t experience troubles or pain or suffering. They do. Garret Brace faced dark thunderclouds, and other characters face problems of their own. But just as Brace found blue skies above, so Cordair’s other characters think and choose and ultimately persevere.

Speaking of the world he writes about in the introduction to Lunch Break, Cordair says the stories come from the conviction that “this earth is a place where we belong” and “that ours is a benevolent, rewarding universe for anyone who chooses to pursue happiness with integrity, passion and perseverance” (p. x).

That premise comes across in each story even though Cordair does not state it explicitly in any of them. Again, Cordair shows such things rather than tells of them.

And while Cordair is expert at painting highly detailed pictures with his words, he also expertly integrates his characters, their choices, and their actions into meaningful themes. The stories in Lunch Break, and the poems that are sprinkled throughout, speak to the importance of integrity, justice, and wholeheartedly pursuing what you love. The stories are full of beautiful lines, priceless events, and unexpected plot twists—from a meaning-packed “I can and I do” in “A Prelude to Pleasure,” to a knee to the groin in “The Seduction of Santi Banesh,” to countless others that I dare not mention for fear of robbing you of the pleasure of reading the stories yourself.

Of course, returning to the description of the movie with which I began, you might say that it didn’t reflect a benevolent sense of life, or characters acting with integrity and justice, or characters ultimately achieving values. And, on the basis of that partial description of the film, you’d be right. But that scene continues in the story, and, characteristic of Cordair’s world, it too comes to a benevolent end.

To discover how that scene proceeds and concludes, and for much more in the way of romantic short stories, check out “A Prelude to Pleasure” and the other fiction included in Lunch Break.

I put off reading these short stories for too long, expecting what praise I had heard to be inflated. But, for all of the above reasons and many more, I wish I hadn’t.

![[TEST] The Objective Standard](https://test.theobjectivestandard.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/logo.png)