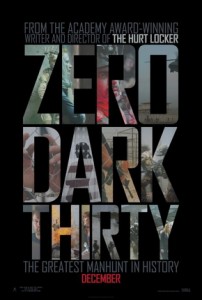

Zero Dark Thirty, directed by Kathryn Bigelow. Written by Mark Boal. Starring Jessica Chastain, Jason Clarke, Joel Edgerton, Jennifer Ehle, Mark Strong, and James Gandolfini. Released by Columbia Pictures. Rated R for strong violence including brutal disturbing images, and for language. Running time: 157 minutes.

Zero Dark Thirty is the story of a heroine.

It chronicles the efforts of Maya (Jessica Chastain), a CIA analyst who relentlessly hunts Osama bin Laden in the years following 9/11. “Relentless” is the right word to describe this young American woman. Recruited out of school by the CIA, for virtually a decade she does nothing but search for bin Laden. Numerous obstacles impede her. None daunt her. None stop her.

Her leads dry up. The Taliban murder her allies. The CIA bureaucracy does not heed her. She persists. Viewers know how this story ends, but that does not matter. The film is a mesmerizing, white-knuckle tale of a woman’s years-long quest to avenge 9/11 and protect America.

The film is about war—but not primarily. It is about politics—but not predominantly. It raises questions regarding the morality of torturing terrorists—but this is not its focus. And, although it depicts the SEAL team’s raid that kills bin Laden, this is not its focus, either.

Zero Dark Thirty is the story of Achilles, of El Cid, of Patton—not so much a tale of war as of a lethal warrior on a ruthless quest whose sole alternative to victory is not defeat but death. Maya will never give up. If bin Laden could have known that such a killer hunted him, perhaps surrender or suicide would have crossed his mind. After the Taliban kill Maya’s colleagues and her lead is expunged, she is asked what she will do. She responds: “I will smoke everyone involved in this op, and then I will kill bin Laden.” Observing this warrior cleave through obstacles, even the most jaded of modern cynics might suppose that if the republic had but two more like Maya—one serving as POTUS, and the other as director of central intelligence—the war against Islamic totalitarianism could be as decisively concluded as was the war against fascism.

The focus of the story is the work of Maya and her CIA colleagues (effectively portrayed by a cast of pros) in the hunt for bin Laden. Part of the genius of Bigelow and Boal is that they take a story in which the heroine spends a great deal of time peering into a computer screen—and a story about which everyone knows the outcome—and transform it into the most gripping, blow-to-the-windpipe thriller of the year. Did you think Argo was a suspenseful fictionalized depiction of CIA heroics in the war against Islamist fanatics? (It was.) Zero Dark Thirty is orders of magnitude more gripping. Bigelow and Boal’s case study of Maya takes viewers into depths of intensity unmatched by any recent film in this genre.

It is understandable that we are intrigued by a fanatic of this sort, someone consumed by a mission, a quest, a crusade—especially in service of the innocent against the evil. We sense or explicitly know that this is the way great tasks are accomplished, the way human life is advanced. Thomas Edison once said he worked eighteen hours a day for forty-five years. Maya matches that tenacity. What is her backstory? Does she have a family? A love life? Friends? The movie doesn’t tell us. It doesn’t matter. Those values that are of immense importance to mere mortals are trivial niceties—distractions, really—to Maya the Merciless. Her meaning in life is to kill bin Laden. The viewer is with her, step by step, on this single-minded quest.

Kathryn Bigelow has found her niche as a director. She brings a deft touch to the portrayal of war’s hideous violence. She does not overwhelm the viewer, as do several of her Hollywood colleagues, with exploding shells, severed body parts, and a screen full of gore. No doubt, as Sherman observed, war is hell. But Bigelow’s hell is a more artistic, less documentary version. Bombs occasionally detonate (sometimes they don’t), but not before the perennial threat wrings from her characters and her audience every drop of nerve-jangled suspense possible. The horror of war, in Bigelow’s universe, lies in the realization that you, and those you cherish, exist chronically one heartbeat away from obliteration.

In Zero Dark Thirty, Bigelow and Boal continue a fascinating if flawed study, begun in The Hurt Locker, of a lethal warrior of Spartan valor, whose life outside the mission holds nothing. Clearly the writer and director of these stunning films hold the modernist premise that if heroes exist they are necessarily flawed. We are permitted to observe human greatness for a moment—but only if, with it, we witness the bleak emptiness of a hero’s life. Yet are Bigelow and Boal (or anyone) genuinely fascinated by empty lives? No. They make, and audiences flock to, films about heroes.

Bigelow and Boal’s subconscious fascination with human greatness overshadows their obligatory lip service to men’s character flaws. The heart, soul, and unstated yearning with which they write and direct are clearly simpatico with man’s striving toward excellence. The vision in these films is epic and almost Greek: men suffer from hubris and every other spiritual affliction—but, by God, they can be great.

Although Bigelow and Boal undoubtedly intended for Chastain’s performance to leave the audience with a wistful, haunted quality—whither now, Maya?—it does not. The audience knows that the girl who got bin Laden can figure out whether she wants to go back to school or get married or rear a family. Successfully spearheading the most intense manhunt of our age may form the high point of her CIA career, but is the balance of her life to be nothing but problematic anticlimax? If the film shows us one thing it is that Maya is not one to be strung out by ennui. The girl who found bin Laden will find her way.

The final word on this exceptional film is as simple and unyielding as Maya’s mind-set: see it.

![[TEST] The Objective Standard](https://test.theobjectivestandard.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/logo.png)