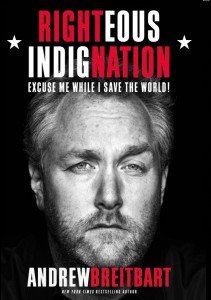

Righteous Indignation: Excuse Me While I Save the World, by Andrew Breitbart. New York: Grand Central Publishing, 2011. 272 pp. $27.99 (hardcover).

In Righteous Indignation, Andrew Breitbart (1969–2012) targets the political left’s death grip on American culture. Focusing on the arts and entertainment, on academia, and (most important to him) on the media, he critiques the ideas of intellectuals who fundamentally oppose America’s founding ideals, and he provides rational advice for liberty lovers who want to regain the culture.

Citing the cause of his righteous indignation, Breitbart writes:

If the political left weren’t so joyless, humorless, intrusive, overtaxing, anarchistic, controlling, unrealistic, hypocritical, angry, intolerant—and if the political left weren’t hell-bent on expansion of said unpleasantness into all aspects of my family’s life—the truth is, I would not be in your life.

If America’s pop-culture ambassadors like Alec Baldwin and Janeane Garofolo didn’t come back from foreign trips to tell us how much they hate us, if my pay cable didn’t highlight a comedy show every week that called me a racist for embracing constitutional principles and limited government, I wouldn’t be at Tea Parties screaming my love for this great, charitable, and benevolent country. The left made me do it! I swear! I am a reluctant cultural warrior. (pp. 10–11)

Righteous Indignation is part autobiography, part cultural history, and part manifesto.

Breitbart’s personal story begins in Southern California, where his hard-working, value-oriented parents saved enough money to send him away to college. Young Andrew, however, did not take his education seriously; he chose to attend Tulane University in New Orleans, in part because “you could go to a different bar every night during your time at Tulane, and never repeat” (p. 19). While there he chose the vague major of “American Studies,” in which he learned nothing about the Founding Fathers, except that they were slaveholders.

After Breitbart graduated, his future father-in-law, the actor Orson Bean, suggested that he listen to Rush Limbaugh. Breitbart expected to hear racist and misogynist tirades but instead heard about the glory of “American exceptionalism.” Thus he was already rethinking his left-leaning views when he discovered and ultimately met Matt Drudge, who used a new tool—the Internet—to chip away at the mainstream media’s virtual monopoly on cultural commentary. Drudge introduced Breitbart to Arianna Huffington, who hired him as director of research for her startup media outlet, where he integrated his passion for facts, ideas, and communication as he began his career in real-time, Web-based news aggregate services.

Breitbart learned from his alternative media mentors the importance of redirecting the mainstream political discussion by uncovering alarming facts, events, and scandals that major media outlets then felt obliged to report. He showcased this approach years later when a filmmaker named James O’Keefe approached him with several undercover videos O’Keefe had recorded. The videos exposed how staffers at the Association of Community Organizers for Reform Now (ACORN) sought to provide government aid to O’Keefe’s (fake) import sex-slave operation. Breitbart announced the story on his new website the same day the president attempted to convince an unwilling public that ObamaCare was in their best interest—taking the thunder out of the president’s agenda. The “September 10, 2009, launch of BigGovernment.com did something President Obama couldn’t: it created the first and only bipartisan vote of consequence of his presidency—the congressional defunding of ACORN” (p. 2).

As a work on history, Righteous Indignation demonstrates that ideas have consequences. While examining America’s ideological transition, Breitbart connects dots from European thinkers such as Rousseau, Hegel, and Marx to the Progressive movement that ushered in Teddy Roosevelt, whose basic ideas are reflected in his statement, “To hell with the Constitution when the people want coal!” (p. 110). In particular, Breitbart exposes Herbert Marcuse as a major culprit in the culture’s intellectual disintegration.

Marcuse’s mission was to dismantle American society by using diversity and “multiculturalism” as crowbars with which to pry the structure apart, piece by piece. Marcuse’s theory of “victim groups” was the new proletariat, combined with Horkheimer’s critical theory, found an outlet in academia, where it became the basis for the post-structural movement—Gender Studies, LGBT/“Queer” Studies, African-American Studies, Chicano Studies, etc. All of these “Blank Studies” brazenly describe their mission as tearing down . . . the accepted traditions of Western culture, and placing in their stead a moral relativism that equates all cultures and all philosophies—except for Western civilization, culture, and philosophy, which are “exploitative” and “bad.” (p. 121)

Breitbart then turns to another major contributor to the rise of the New Left, Saul Alinsky, whose book Rules for Radicals heavily influenced the left:

[I]f Marcuse was the Jesus of the New Left, then Alinsky was his Saint Paul, proselytizing and dumbing down Marcuse’s message, making it practical and convincing leaders to make it the official religion of the United States, even if that meant discarding the old secular religion of the United States, the Constitution. . . .

His bottom line is plain and unvarnished: Kick ass and then pretend you were doing the moral thing. Lie, cheat, and steal for your victory. Always cloak your goals in widely agreed-upon American terms that people buy into. Things like the Declaration of Independence or the “common welfare” provision of the Constitution. Sure, you may be standing for none of those things. But that doesn’t matter—victory is what matters. It’s the Chicago way. (pp. 125,130)

The final segment of Righteous Indignation is Breitbart’s call to action. He describes his own battles, as when he appeared on Real Time with Bill Maher in 2009 and “things got nasty” with Maher, the other guest, and the audience after he mentioned the brisk sales of Ayn Rand’s books (p. 141). Clearly, he knew how to rile the relativist left. But he also distinguished himself to some extent from the religious right. In his chapter “Pragmatic Primer for Realistic Revolutionaries,” Breitbart urges liberty activists to use and appeal to reason, an approach that set him apart from faith-oriented conservatives. He advises:

[Y]ou can always puncture [the left’s] balloon with one word: why. Asking them to provide evidence for their assertions is always fun, and it’s even more fun asking them to provide the sources for that evidence. Attacking the fundamental basis of their arguments is fun, too—if they tell you health care is a right, for example, ask why. Liberals don’t have a why, other than their own utopianism and their dyspeptic view of the status quo and America. Reason is not their strong suit—emotion is. Force them to play on the football field of reason. (p. 158)

Breitbart recounts how he proudly assumed the role of Tea Party protector. On April 15, 2009, when the Tea Party took the country by storm, he embraced its members as the only consistent defenders of the Constitution at that time. And he warned Tea Partiers that they must be prepared for every kind of irrational assault on their efforts to defend liberty. Tea Partiers, he said, would “be labeled as racists and hatemongers and violent criminals, that they’d be depicted as the dregs of society, people to be excluded from dinner parties because of their made-up closet KKK status” (p. 194). This, of course, is precisely what happened.

Breitbart concludes his manifesto by projecting what his “Big” websites (all subsumed under Breitbart.com) will focus on in the future:

Over the next few years, the Bigs will expand beyond Hollywood (television, film, music), Journalism (media criticism), Government, and Peace (national security). We will take on Education, Tolerance (political correctness), and beyond. It is not just a political war, it is a cultural war, and our audacious goal is to change the big narrative. Please, tell me it cannot be done! (p. 212)

Aside from excessive profanity, Righteous Indignation does not have flaws worth mentioning. It is a timely book by a raconteur, entrepreneur, risk taker, and cultural warrior. Although Breitbart died too young, he left a legacy and a plan of action for those who are inspired to take up intellectual arms against the left’s assault on all things good. And Breitbart not only reminds his readers to have fun while fighting for their values—he shows us how to do so.

Breitbart had Big Fun exposing the evils of leftists, and although he is gone, his example is here for us to embrace. Let’s expose the evils of the left, and let’s have fun doing it. Big Fun. Breitbart Fun.

![[TEST] The Objective Standard](https://test.theobjectivestandard.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/logo.png)