New York: Simon & Schuster, 2017.

599 pp. $35 (hardcover).

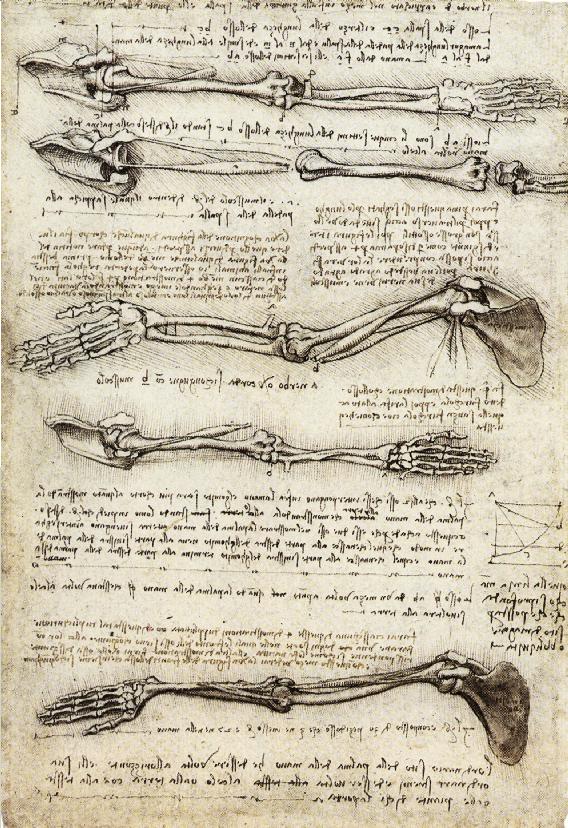

While Leonardo da Vinci was refining the Mona Lisa, he was also involved in dissecting human cadavers in a hospital’s morgue. Among his anatomical interests were the muscles that move the lips. At about the same time he discovered that the upper lip doesn’t pucker alone, he was perfecting what would become the most notable feature of the most recognizable painting in history: Mona Lisa’s smile.

On a page in one of his voluminous notebooks—which were filled with everything from his theoretical writings on art and flight to his drawings of horses and a perpetual motion machine—Da Vinci sketched various human mouths, including one smiling gently. In his latest book, Leonardo Da Vinci, biographer Walter Isaacson writes:

Even though the fine lines at the ends of the mouth turn down almost imperceptibly, the impression is that the lips are smiling. . . . Leonardo was able to create an uncatchable smile, one that is elusive if we are too intent on seeing it. The very fine lines at the corner of Lisa’s mouth show a small downturn, just like the mouth floating atop the anatomy sheet [in his notebook]. (489–90)

This backstory on the masterpiece exemplifies Isaacson’s perceptive portrait of the self-taught Renaissance man. Isaacson is a history professor at Tulane University and author of biographies on Benjamin Franklin, Albert Einstein, and Steve Jobs. In his latest work, he surveys Da Vinci’s incredible breadth of interests and spotlights those most integral to his creative genius. He concludes that Da Vinci’s scientific pursuits were as important to him as his artistic endeavors, that he considered the two to be inseparable, and that his innovations would have been impossible without his extreme independence of mind and devotion to understanding the world around him.

Born in Vinci, Italy, in 1452, Da Vinci was fourteen when he apprenticed for artist Andrea del Verrocchio in Florence, a burgeoning city of commerce, art, and humanism. Throughout his life, Da Vinci worked for various aristocrats in Florence and Milan, designing everything from court pageants to implements of war. After living briefly in Rome, he spent his final years with King Francis I in France, where he died in 1519.

The marriage between Da Vinci’s scientific investigations and his art is well documented, starting from the time when he compared swirls of river water to curls in human hair, an analogy he first painted in the locks of an angel while assisting Verrocchio on his Baptism of Christ. These integrations are a major focus of Isaacson’s book.

Da Vinci’s lack of formal education led him to boast that he learned instead from a far worthier source: his own experience. At a time when most were taught that the sun revolved around the earth and that Jesus walked on water, he pursued his own this-worldly interests.

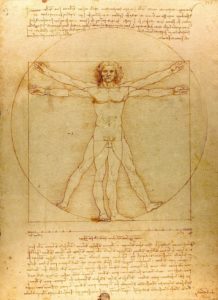

Isaacson contends that Da Vinci’s creative brilliance was rooted in his insatiable curiosity about the physical world. To discover how nature works, Da Vinci conducted experiments and often dismissed classical texts and thinkers. For instance, Vitruvian Man, his famous sketch of the ideally proportioned male, relied mainly on measurements he took from his anatomical studies rather than those handed down by Vitruvius, a Roman engineer who analogized human proportions to architecture. However, later in life, Da Vinci recognized the value of some scholarly texts, including Aristotle’s work on shadows, which guided the experiments that led him to distinguish between multiple categories of shadows.

Isaacson explores how Da Vinci thought, detailing the methods he devised, including his standing order to make more purposeful observations. He also developed a propensity when confronted by a contradiction to follow the new, corrective evidence. Isaacson holds that this was the “key to his creativity” (435).

He shows how Da Vinci’s concentrations in anatomy, engineering, geology, hydrodynamics, geometry, perspective, and optics exerted substantial influence on his art. For example, he relates that the detailed rock formations and flora in both versions of Virgin of the Rocks clearly reveal Da Vinci’s studies in geology and botany. Also, decades after starting his unfinished painting Saint Jerome in the Wilderness, “when his anatomy experiments taught him something new about neck muscles,” Da Vinci updated the emaciated, self-flagellating saint in accordance with his new knowledge (518).

Isaacson details the intricacies of Da Vinci’s innovations in perspective, including those in his unfinished painting Adoration of the Magi and especially The Last Supper. His greatest contribution involved “ways of conveying depth through changes in color and clarity,” writes Isaacson (274). He holds that dimensionality—the illusion of three-dimensional volume on a flat surface—“became the supreme innovation of Renaissance art” mainly due to Da Vinci’s work in perspective (2).

Take, for instance, sfumato, a technique Da Vinci invented, which softens otherwise unnatural outlines and borders. Quoting from Da Vinci’s notebooks, Isaacson explains how Da Vinci’s thinking led him to this innovation:

“Do not edge contours with a definite outline, because the contours are lines, and they are invisible, not only from a distance, but also close at hand,” he wrote. “If the line and also the mathematical point are invisible, the outlines of things, also being lines, are invisible, even when they are near at hand.” Instead an artist needs to represent the shape and volume of objects by relying on light and shadow. “The line forming the boundary of a surface is of invisible thickness. Therefore, O painter, do not surround your bodies with lines.” (269)

Isaacson also attributes to Da Vinci a new style of painting that he calls the “psychological portrait,” which conveys emotions through gestures, facial expressions, and other bodily movements. This pioneering style culminated in The Last Supper, in which the scale of emotions Jesus and his gesturing disciples evoke is, according to Isaacson, “the grandest and most vibrant example of this in the history of art” (282).

By contrast to his artistic innovations, Da Vinci’s scientific advances went largely unknown during his life, in part because he never published his findings, many of which were rediscovered centuries later. Isaacson discusses Da Vinci’s most significant achievements, including his groundbreaking and exquisite anatomical illustrations of the human smile, skull, and teeth; his discovery of heart valves; and the process that causes arteriosclerosis.

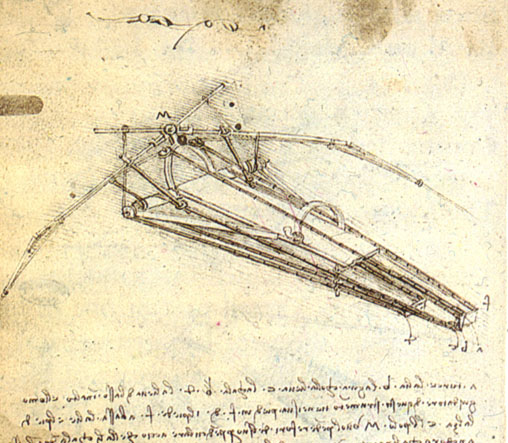

In geography, Da Vinci pioneered studies of fossil traces, and his research into flight led him to show, for example, that the principles of dynamics that explain how birds stay aloft in air are different than those that explain how they stay afloat in water. “He not only got the basic principles of fluid dynamics correct,” writes Isaacson, “but he was able to turn his insights into rudimentary theories that foreshadow those of Newton, Galileo, and Bernoulli” (184).

Da Vinci also made progress in cartography, which enabled him to draw an accurate bird’s-eye map of Imola (an Italian city), and he developed preliminary though impractical ideas for an armored tank, machine gun, scuba equipment, and parachute.

Art scholars have criticized Da Vinci for allegedly squandering his time on such nonartistic pursuits as his hundreds of formulas to square the circle and numerous observations of water flow. Some theorize that these tangential obsessions distracted him from finishing many of his art projects.

But Isaacson offers a contrarian perspective that is a particular virtue of his book. He persuasively contends that Da Vinci was able to create world-famous masterpieces because he thought himself “just as much a man of science and engineering” (1). He challenges the most prominent proponent of such critiques, Da Vinci scholar Kenneth Clark, writing:

Clark was dismissive after rattling off a list of these nonpainterly passions: “One day he could be deciding on the form of the choir stalls in the Duomo; another, acting as military engineer in the war against Venice; another, arranging pageants for the entry of Louis XII into Milan.” Clark added sorrowfully, “It was a variety of employment which Leonardo enjoyed, but which has left posterity the poorer.”

Perhaps Clark is right, in that our store of art does not include a [finished] Battle of Anghiari or other potential masterpieces. But if posterity is poorer because of the time Leonardo spent immersed in passions from pageantry to architecture, it is also true that his life was richer. (392–93)

Here, Isaacson takes a praiseworthy position. He repeatedly and approvingly states that Da Vinci was devoted to these interests, not only to inform his art or to move science forward, but for something paramount to him: the satisfaction of his own undying curiosity and impassioned wonderment with nature. In one exemplary passage, he writes:

The trove of treaties that he left unpublished testifies to the unusual nature of what motivated him. He wanted to accumulate knowledge for its own sake, and for his own personal joy, rather than out of a desire to make a public name for himself as a scholar or to be part of the progress of history. (423)

Isaacson notes instances of others independently making scientific discoveries that Da Vinci had made centuries earlier, and he is admirably careful not to attribute to him more than he deserves. Curiously, although he often praises Da Vinci effusively, Isaacson refrains from drawing a justifiable conclusion—namely, that given his many original artistic achievements, Da Vinci may have been history’s most innovative painter.

Of tremendous value—although somewhat unusual for a biography—Isaacson devotes several concluding pages to encouraging readers to model the polymath’s traits, especially his level of curiosity and depth of observation. This self-improvement element may also help readers to better understand Da Vinci’s hard-earned genius.

Diligently researched and adorned with outstanding illustrations, Isaacson’s Leonardo Da Vinci distills the fundamental attributes of the complex Renaissance man who, whatever his intent, has left posterity the richer.

Click To Tweet

![[TEST] The Objective Standard](https://test.theobjectivestandard.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/logo.png)